THE CASE of ICHERI SHEHER, BAKU Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

Of Palaces, Hunts, and Pork Roast: Deciphering the Last Chapters of the Capitulary of Quierzy (a. 877) Martin Gravel Politics depends on personal contacts.1 This is true in today’s world, and it was certainly true in early medieval states. Even in the Carolingian empire, the larg- est Western polity of the period, power depended on relations built on personal contacts.2 In an effort to nurture such necessary relationships, the sovereign moved with his court, within a network of important political “communication centres”;3 in the ninth century, the foremost among these were his palaces, along with certain cities and religious sanctuaries. And thus, in contemporaneous sources, the Latin term palatium often designates not merely a royal residence but the king’s entourage, through a metonymic displacement that shows the importance of palatial grounds in * I would like to thank my fellow panelists at the International Medieval Congress (Leeds, 2011): Stuart Airlie, Alexandra Beauchamp, and Aurélien Le Coq, as well as our session organizer Jens Schneider. This paper has greatly benefited from the good counsel of Jennifer R. Davis, Eduard Frunzeanu, Alban Gautier, Maxime L’Héritier, and Jonathan Wild. I am also indebted to Eric J. Goldberg, who was kind enough to read my draft and share insightful remarks. In the final stage, the precise reading by Florilegium’s anonymous referees has greatly improved this paper. 1 In this paper, the term politics will be used in accordance with Baker’s definition, as rephrased by Stofferahn: “politics, broadly construed, is the activity through which individuals and groups in any society articulate, negotiate, implement, and enforce the competing claims they make upon one another”; Stofferahn, “Resonance and Discord,” 9. -

15 Reasons to Visit Baku and Azerbaijan Now Recommended by the Savvy Concierge Team at Four Seasons Hotel Baku

15 Reasons to Visit Baku and Azerbaijan Now Recommended by the savvy Concierge team at Four Seasons Hotel Baku March 16, 2015, Baku, Azerbaijan Experience one of the world’s most exciting cities and let the Concierge team at Four Seasons Hotel Baku be the guide with these recommendations: 1. Icherisheher – The Old City, at 22 hectares (54 acres) in size, it contains hundreds of historical monuments, four of which are of world importance and 28 of which are of local importance. Visit souvenir, carpet and antique shops, and workshops of local handicrafts. It became the first location in Azerbaijan to be 1 classified as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. You can see Maiden Tower, Market Square, Karvan Saray Bukhara, Karvan Saray Multani, Baku Khan's Residence, Shirvan Shahs' Palace, Aga-Mikhail bath house, Double Gates, and several old mosques in Old town. 2. Old Oil Fields - The fame of Baku as a new industrial revolution capital started with strong fountains of oil in 1872 in the outskirts of the villages of Balakhani, Sabunchu and Ramana. Within a few years oil- bearing parts of Absheron turned into densely populated regions. More than a hundred wells were drilled and on the first stage up to forty small firms functioned in the outskirts of Balakhani. The sharpest problem of oil industrialists of that time was the transportation of oil from Balakhani to Baku. In 1877 a pood of oil cost 3 cents and its transportation to the city cost 20 cents. In 1863 the professor-chemist Mendeleev recommended building an oil pipeline during his visit to Baku, but the volume of production was not big then and that’s why the proposal was never realized. -

Download Tour

Ancient and Modern Starting From :Rs.:18641 Per Person 4 Days / 3 Nights Baku .......... Package Description Ancient and Modern Baku Airport - Hotel (Baku) Welcome to Baku. Upon arrival at the Airport you will be met by our local representative who will transfer you to the city hotel. .......... Itinerary Day.1 Half Day free time in Baku (No Services included) (Baku) There is no service included, you may spend time, as per your interests. Meals:N.A Day.2 Half Day Baku City Tour (Baku) Visit Memory Alley – “Shehidler Khiyabany”,High Land park it opens up a great panoramic view of Baku city. Continue exploring architecture of the 14-20th centuriesin the Nizami Street, Fountain Square, Nizami Ganjavi monument. Move to the old part of the city – Icheri Sheher. Visit Maiden Tower, Shirvan Shahs’ Palace, Caravanserai and bath, Carpet and antique shops, market square with numerous art studios and souvenirs stalls. An excellent round-up to the city tour will be a visit biggest national park Boulevard. Entrance fee is included Video Links : https://youtu.be/nbHpc0NurAo Copyright © www.funnfunholiday.com Meals:N.A Day.3 Full Day Gabala Tour From Baku (Baku) In the morning, depart Baku and drive to Gabala town. On the way, visit Diri Baba mausoleum in Maraza village. Continue to Shamakha, where you will visit historical Juma Mosque, Yeddi Gumbez Mausoleum, and the Shirvan Shah's family grave yard. Continue driving to Gabala , visit the Nohur lake, Gabaland entertainment,Cable way,Shooting centre,.Return to baku. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CtpNvXdAPrc Meals:N.A Day.4 Half Day free time in Baku (No Services included) (Baku) There is no service included, you may spend time, as per your interests. -

Azerbaijan Page 1 of 8

Azerbaijan Page 1 of 8 Azerbaijan BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR International Religious Freedom Report 2009 October 26, 2009 The Constitution provides for freedom of religion. On March 18, 2009, however, a national referendum approved a series of amendments to the Constitution; two amendments limit the spreading of and propagandizing of religion. Additionally, on May 8, 2009, the Milli Majlis (Parliament) passed an amended Law on Freedom of Religion, signed by the President on May 29, 2009, which could result in additional restrictions to the system of registration for religious groups. In spite of these developments, the Government continued to respect the religious freedom of the majority of citizens, with some notable exceptions for members of religions considered nontraditional. There was some deterioration in the status of respect for religious freedom by the Government during the reporting period. There were changes to the Constitution that undermined religious freedom. There were mosque closures, and state- and locally sponsored raids on evangelical Protestant religious groups. There were reports of monitoring by federal and local officials as well as harassment and detention of both Islamic and nontraditional Christian groups. There were reports of discrimination against worshippers based on their religious beliefs, largely conducted by local authorities who detained and questioned worshippers without any legal basis and confiscated religious material. There were sporadic reports of societal abuses or discrimination based on religious affiliation, belief, or practice. There was some prejudice against Muslims who converted to other faiths, and there was occasional hostility toward groups that proselytized, particularly evangelical Christians, and other missionary groups. -

IAUP Baku 2018 Semi-Annual Meeting

IAUP Baku 2018 Semi-Annual Meeting “Globalization and New Dimensions in Higher Education” 18-20th April, 2018 Venue: Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers Website: https://iaupasoiu.meetinghand.com/en/#home CONFERENCE PROGRAMME WEDNESDAY 18th April 2018 Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers 18:30 Registration 1A, Mehdi Hüseyn Street Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers, 19:00-21:00 Opening Cocktail Party Uzeyir Hajibeyov Ballroom, 19:05 Welcome speech by IAUP President Mr. Kakha Shengelia 19:10 Welcome speech by Ministry of Education representative 19:30 Opening Speech by Rector of ASOIU Mustafa Babanli THURSDAY 19th April 2018 Visit to Alley of Honor, Martyrs' Lane Meeting Point: Foyer in Fairmont 09:00 - 09:45 Hotel 10:00 - 10:15 Mr. Kakha Shengelia Nizami Ganjavi A Grand Ballroom, IAUP President Fairmont Baku 10:15 - 10:30 Mr. Ceyhun Bayramov Deputy Minister of Education of the Republic of Azerbaijan 10:30-10:45 Mr. Mikheil Chkhenkeli Minister of Education and Science of Georgia 10:45 - 11:00 Prof. Mustafa Babanli Rector of Azerbaijan State Oil and Industry University 11:00 - 11:30 Coffee Break Keynote 1: Modern approach to knowledge transfer: interdisciplinary 11:30 - 12:00 studies and creative thinking Speaker: Prof. Philippe Turek University of Strasbourg 12:00 - 13:00 Panel discussion 1 13:00 - 14:00 Lunch 14:00 - 15:30 Networking meeting of rectors and presidents 14:00– 16:00 Floor Presentation of Azerbaijani Universities (parallel to the networking meeting) 18:30 - 19:00 Transfer from Farimont Hotel to Buta Palace Small Hall, Buta Palace 19:00 - 22:00 Gala -

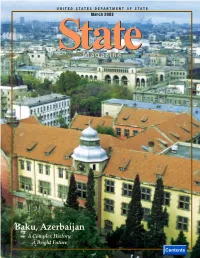

Baku, Azerbaijan a Complex History, a Bright Future in Our Next Issue: En Route to Timbuktu

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF STATE March 2003 StateStateMagazine Baku, Azerbaijan A Complex History, A Bright Future In our next issue: En Route to Timbuktu Women beating rice after harvest on the irrigated perimeter of the Niger River. Photo Trenkle Tim by State Magazine (ISSN 1099–4165) is published monthly, except State bimonthly in July and August, by the U.S. Department of State, Magazine 2201 C St., N.W., Washington, DC. Periodicals postage paid at Carl Goodman Washington, D.C., and at additional mailing locations. POSTMAS- EDITOR-IN-CHIEF TER: Send changes of address to State Magazine, HR/ER/SMG, Dave Krecke SA-1, Room H-236, Washington, DC 20522-0108. State Magazine WRITER/EDITOR is published to facilitate communication between management Paul Koscak and employees at home and abroad and to acquaint employees WRITER/EDITOR with developments that may affect operations or personnel. Deborah Clark The magazine is also available to persons interested in working DESIGNER for the Department of State and to the general public. State Magazine is available by subscription through the ADVISORY BOARD MEMBERS Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Florence Fultz Washington, DC 20402 (telephone [202] 512-1800) or on the web at CHAIR http://bookstore.gpo.gov. Jo Ellen Powell For details on submitting articles to State Magazine, request EXECUTIVE SECRETARY our guidelines, “Getting Your Story Told,” by e-mail at Sylvia Bazala [email protected]; download them from our web site Cynthia Bunton at www.state.gov/m/dghr/statemag;or send your request Bill Haugh in writing to State Magazine, HR/ER/SMG, SA-1, Room H-236, Bill Hudson Washington, DC 20522-0108. -

Baku Airport Bristol Hotel, Vienna Corinthia Hotel Budapest Corinthia

Europe Baku Airport Baku Azerbaijan Bristol Hotel, Vienna Vienna Austria Corinthia Hotel Budapest Budapest Hungary Corinthia Nevskij Palace Hotel, St Petersburg St Petersburg Russia Fairmont Hotel Flame Towers Baku Azerbaijan Four Seasons Hotel Gresham Palace Budapest Hungary Grand Hotel Europe, St Petersburg St Petersburg Russia Grand Hotel Vienna Vienna Austria Hilton DoubleTree Zagreb Zagreb Croatia Hilton Hotel am Stadtpark, Vienna Vienna Austria Hilton Hotel Dusseldorf Dusseldorf Germany Hilton Milan Milan Italy Hotel Danieli Venice Venice Italy Hotel Palazzo Parigi Milan Italy Hotel Vier Jahreszieten Hamburg Hamburg Germany Hyatt Regency Belgrade Belgrade Serbia Hyatt Regenct Cologne Cologne Germany Hyatt Regency Mainz Mainz Germany Intercontinental Hotel Davos Davos Switzerland Kempinski Geneva Geneva Switzerland Marriott Aurora, Moscow Moscow Russia Marriott Courtyard, Pratteln Pratteln Switzerland Park Hyatt, Zurich Zurich Switzerland Radisson Royal Hotel Ukraine, Moscow Moscow Russia Sacher Hotel Vienna Vienna Austria Suvretta House Hotel, St Moritz St Moritz Switzerland Vals Kurhotel Vals Switzerland Waldorf Astoria Amsterdam Amsterdam Netherlands France Ascott Arc de Triomphe Paris France Balmoral Paris Paris France Casino de Monte Carlo Monte Carlo Monaco Dolce Fregate Saint-Cyr-sur-mer Saint-Cyr-sur-mer France Duc de Saint-Simon Paris France Four Seasons George V Paris France Fouquets Paris Hotel & Restaurants Paris France Hôtel de Paris Monaco Monaco Hôtel du Palais Biarritz France Hôtel Hermitage Monaco Monaco Monaco Hôtel -

HIST WOR Photo TORIC CENT RLD HERITA O 1-1. Histor RE of SHEK

Photo 1-1. Historic centre of Sheki HISTORIC CENTRE OF SHEKI WITH THE KHAN’S PALACE WORLD HERITAGE NOMINATION FILE 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary_____________________________________ 5 1. Identification of the Property ____________________________ 14 1.a Country____________________________________________ 15 1.b State, Province or Region______________________________ 16 1.c Name of Property___________________________________ 18 1.d Geographical coordinates to the nearest second____________ 19 1.e Maps and plans, showing the boundaries of the nominated property and buffer zone_____________________ 19 1.f Area of nominated property and proposed buffer zone________ 21 2. Description____________________________________________ 22 2.a Description of Property________________________________ 23 2.b History and Development ______________________________ 53 3. Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief synthesis_____________________________________ 73 3.1.b Criteria under which inscription is proposed______________ 74 3.1.c Statement of Integrity_________________________________ 82 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity______________________________ 85 3.1.e Protection and management requirements__________________ 93 3.2 Comparative Analysis__________________________________ 95 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value___________ 110 4. State of conservation and factors affecting the Property_______ 113 4a Present state of conservation_____________________________ 114 4b Factors affecting the property____________________________ 123 -

Mr. Ilham Aliyev Presidential Palace Istiglaliyyat Street 19 1066 Baku Republic of Azerbaijan Fax: +994124923543 and +994124920625 E-Mail: [email protected]

Mr. Ilham Aliyev Presidential Palace Istiglaliyyat street 19 1066 Baku Republic of Azerbaijan Fax: +994124923543 and +994124920625 E-mail: [email protected] 23 April 2012 Urgent appeal for the prompt and impartial investigation, followed by a fair and open trial, of the attack against journalists Idrak Abbasov, Gunay Musayeva and Adalat Abbasov Mr. President, On 18 April 2012 in Baku, security guards attacked a prominent Azerbaijani journalist, Idrak Abbasov. This violent assault constitutes another case out of a long list of journalists harassed and attacked in Azerbaijan. The authorities of Azerbaijan bear the international responsibility to fully guarantee and promote the right to freedom of expression, as well as to carry out a prompt and impartial investigation and bring those responsible for these hideous crimes to justice in fair and open trial. Idrak Abbasov, a reporter of the newspaper Zerkalo and of the Institute for Reporters' Freedom and Safety (IRFS), was beaten by security guards of the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR) whilst filming the confrontation between the residents of the settlement of Sulutepe on the outskirts of Baku and SOCAR, which is in charge of demolishing irregular homes in the area. Idrak Abbasov was wearing clear journalist identification when he was approached by the security guards and consecutively beaten up during 5 to 7 minutes. The journalist – unconscious, coughing up blood, with many bruises and hematomas – was taken to the hospital. According to doctors, his present state of health is very poor and he suffers from serious head and body traumas. His brother, Adalat Abbasov and a female journalist Gunay Musayeva were also assaulted. -

Walled City of Baku with the Shirvanshah's Palace and Maiden Tower (2000)

Walled City of Baku with the Shirvanshah's Palace and Maiden Tower (2000) Baku (Azerbaijani: Bakı), sometimes known as Baky or Baki, is the capital, the largest city, and the largest port of Azerbaijan. Located on the southern shore of the Absheron Peninsula, the city consists of two principal parts: the downtown and the old Inner City (21,5 ha). As of January 1, 2003 the population was 1,827,500 of which 153,400 were internally displaced persons and 93,400 refugees.Baku is a member of Organization of World Heritage Cities and Sister Cities International. The city is also bidding for the 2016 Summer Olympics. Baku is divided into eleven administrative districts (Azizbeyov, Binagadi, Qaradagh, Narimanov, Nasimi, Nizami, Sabayil, Sabunchu, Khatai, Surakhany and Yasamal) and 48 townships. Among these are the townships on islands in the Bay of Baku and the town of Oil Rocks built on stilts in the Caspian Sea, 60 km away from Baku. The first written evidence for Baku is related to the 6th century AD. The city became important after an earthquake destroyed Shemakha and in the 12th century, ruling Shirvanshah Ahsitan I made Baku the new capital. In 1501 shah Ismail I Safavi laid a siege to Baku. At this time the city was however enclosed with the lines of strong walls, which were washed by sea on one side and protected by a wide trench on land. In 1540 Baku was again captured by the Safavid troops. In 1604 the Baku fortress was destroyed by Iranian shah Abbas I. On June 26, 1723 after a lasting siege and firing from the cannons Baku surrendered to the Russians. -

Arrival in Baku Itinerary for Azerbaijan, Georgia

Expat Explore - Version: Thu Sep 23 2021 16:18:54 GMT+0000 (Coordinated Universal Time) Page: 1/15 Itinerary for Azerbaijan, Georgia & Armenia • Expat Explore Start Point: End Point: Hotel in Baku, Hotel in Yerevan, Please contact us Please contact us from 14:00 hrs 10:00 hrs DAY 1: Arrival in Baku Start in Baku, the largest city on the Caspian Sea and capital of Azerbaijan. Today you have time to settle in and explore at leisure. Think of the city as a combination of Paris and Dubai, a place that offers both history and contemporary culture, and an intriguing blend of east meets west. The heart of the city is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, surrounded by a fortified wall and pleasant pedestrianised boulevards that offer fantastic shopping opportunities. Attractions include the local Carpet Museum and the National Museum of History and Azerbaijan. Experiences Expat Explore - Version: Thu Sep 23 2021 16:18:54 GMT+0000 (Coordinated Universal Time) Page: 2/15 Arrival. Join up with the tour at our starting hotel in Baku. If you arrive early you’ll have free time to explore the city. The waterfront is a great place to stroll this evening, with a cooling sea breeze and plenty of entertainment options and restaurants. Included Meals Accommodation Breakfast: Lunch: Dinner: Hotel Royal Garden DAY 2: Baku - Gobustan National Park - Mud Volcano Safari - Baku Old City Tour After breakfast, dive straight into exploring the history of Azerbaijan! Head south from Baku to Gobustan National Park. This archaeological reserve is home to mud volcanoes and over 600,000 ancient rock engravings and paintings. -

Sevan Writers' Resort Conservation Management Plan

CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN | 1 Sevan Writers’ Resort Conservation Management Plan Sevan Writers’ Resort Conservation Management Plan The Sevan Writers’ Resort Conservation Management Plan has been developed by urbanlab, commissioned by the Writers’ Union of Armenia with the financing of the Getty Foundation’s Keeping It Modern initiative, within the scope of the Sevan Writers’ Resort Conservation Management Plan Development and Scientific Restoration Project. The project was initiated and elaborated by Ruben Arevshatyan and Sarhat Petrosyan. urbanlab is a Yerevan-based independent urban think-do-share lab, aimed to promote democratization of urban landscape toward sustainable development in its broader understanding. Acknowledgement Conservation Management Plan Consultant: Jonas Malmberg, Álvaro Aalto Foundation (Helsinki) Research Lead: Ruben Arevshatyan Research Coordinator: Nora Galfayan Researcher on Architectural Archives: Aleksandra Selivanova (Moscow) Researcher on Interior and Furniture: Olga Kazakova (Moscow) Lead Architect: Sarhat Petrosyan, urbanlab Structural Consultant: Grigor Azizyan, ArmProject Legal Consultant: Narek Ashughatoyan, Legallab HORECA Consultant: Anahit Tantushyan Glass Structure Consultant: Vahe Revazyan, Gapex HVAC System Consultant: Davit Petrosyan, Waelcon Conservation Architect Consultant: Mkrtich Minasyan Design Consultant: Verena von Beckerat, Heide & Von Beckerath Scientific Consultants: Vladimir Paperny (Los Angeles), Marina Khrustaleva (Moscow), Karen Balyan, Georg Schöllhammer (Austria) Colour