Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communes-Aisne-IDE.Pdf

Commune Arrondissement Canton Nom et Prénom du Maire Téléphone mairie Fax mairie Population Adresse messagerie Abbécourt Laon Chauny PARIS René 03.23.38.04.86 - 536 [email protected] Achery Laon La Fère DEMOULIN Georges 03.23.56.80.15 03.23.56.24.01 608 [email protected] Acy Soissons Braine PENASSE Bertrand 03.23.72.42.42 03.23.72.40.76 989 [email protected] Agnicourt-et-Séchelles Laon Marle LETURQUE Patrice 03.23.21.36.26 03.23.21.36.26 205 [email protected] Aguilcourt Laon Neufchâtel sur Aisne PREVOT Gérard 03.23.79.74.14 03.23.79.74.14 371 [email protected] Aisonville-et-Bernoville Vervins Guise VIOLETTE Alain 03.23.66.10.30 03.23.66.10.30 283 [email protected] Aizelles Laon Craonne MERLO Jean-Marie 03.23.22.49.32 03.23.22.49.32 113 [email protected] Aizy-Jouy Soissons Vailly sur Aisne DE WULF Eric 03.23.54.66.17 - 301 [email protected] Alaincourt Saint-Quentin Moy de l Aisne ANTHONY Stephan 03.23.07.76.04 03.23.07.99.46 511 [email protected] Allemant Soissons Vailly sur Aisne HENNEVEUX Marc 03.23.80.79.92 03.23.80.79.92 178 [email protected] Ambleny Soissons Vic sur Aisne PERUT Christian 03.23.74.20.19 03.23.74.71.35 1135 [email protected] Ambrief Soissons Oulchy le Château BERTIN Nicolas - - 63 [email protected] Amifontaine Laon Neufchâtel sur Aisne SERIN Denis 03.23.22.61.74 - 416 [email protected] Amigny-Rouy Laon Chauny DIDIER André 03.23.52.14.30 03.23.38.18.17 739 [email protected] Ancienville Soissons -

VILLEO-RETZEO Guide A6.Indd

COMMUNAUTÉ DE COMMUNES RETZ-EN-VALOIS VALABLE À PARTIR DU Guide 1er SEPTEMBRE 2020 HORAIRES RÉSEAU DE TRANSPORT ÉDITO 2020 représente une nouvelle étape au service de la mobilité sur notre territoire ! La Communauté de Communes Retz-en-Valois (CCRV), aujourd’hui Autorité Organisatrice de Mobilité, est, à ce titre, habilitée à proposer des solutions en faveur du transport des habitants sur l’ensemble de ses 54 communes. Dès le 1er septembre 2020, Villéo-Retzéo s’agrandit. Nous maintenons les 3 lignes urbaines à Alexandre Villers-Cotterêts et le transport à la demande de MONTESQUIOU SOMMAIRE sur 17 communes au centre de notre territoire. Président de 03 Édito Et, nous créons des lignes supplémentaires adaptées à la réalité des besoins des habitants avec : la Communauté 04 Liste des communes et pages concernées de Communes 05 Règles d’usage • une ligne interurbaine régulière (ligne D) entre Retz-en-Valois les pôles de La Ferté-Milon et Villers-Cotterêts, 06 Plan du réseau de Villers-Cotterêts • des services de transport à la demande (TAD) 07 Plan de la ligne D sectorisés depuis chaque commune du territoire 02 08 à 14 Horaires des lignes A, B, C et D vers un des pôles de services de proximité 03 (La Ferté-Milon, Villers-Cotterêts, Vic-sur-Aisne 15 Les nouveaux services de transport à la demande (TAD) ou Soissons). 16 Carte schématique des services TAD 17 Carte et horaires des services TAD Villers-Cotterêts Concernant les tarifs, les usagers continueront de bénéficier d’un ticket au prix unitaire de 1 €*. 18 Carte et horaires des services TAD La Ferté-Milon 19 Carte et horaires des services TAD Vic-sur-Aisne Toutes ces évolutions sont la résultante d’une étude menée en étroit partenariat avec les communes. -

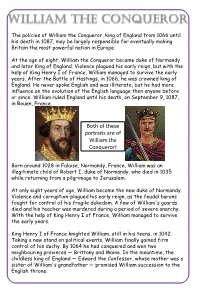

Both of These Portraits Are of William the Conqueror!

The policies of William the Conqueror, king of England from 1066 until his death in 1087, may be largely responsible for eventually making Britain the most powerful nation in Europe. At the age of eight, William the Conqueror became duke of Normandy and later King of England. Violence plagued his early reign, but with the help of King Henry I of France, William managed to survive the early years. After the Battle of Hastings, in 1066, he was crowned king of England. He never spoke English and was illiterate, but he had more influence on the evolution of the English language then anyone before or since. William ruled England until his death, on September 9, 1087, in Rouen, France. Both of these portraits are of William the Conqueror! Born around 1028 in Falaise, Normandy, France, William was an illegitimate child of Robert I, duke of Normandy, who died in 1035 while returning from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. At only eight years of age, William became the new duke of Normandy. Violence and corruption-plagued his early reign, as the feudal barons fought for control of his fragile dukedom. A few of William's guards died and his teacher was murdered during a period of severe anarchy. With the help of King Henry I of France, William managed to survive the early years. King Henry I of France knighted William, still in his teens, in 1042. Taking a new stand on political events, William finally gained firm control of his duchy. By 1064 he had conquered and won two neighbouring provinces — Brittany and Maine. -

Quierzy Info *************

Sortie à la médiathèque Régulièrement notre classe se rend à la médiathèque de Chauny. Ce sont les parents qui nous emmènent là-bas. On lit des livres, on fait des jeux, On trie des ouvrages sur la forêt et on cherche du vocabulaire sur ce thème. Pour cela, on utilise les codes couleurs et les catégories de livres. QUIERZY INFO ************* Merci aux enfants pour leur participation à ce Quierzy Info et pour les petits articles qu’ils nous ont envoyés. Désormais le dernier trimestre scolaire est terminé, nos petits écoliers ont pu profiter de quelques sorties bien Bulletin municipal n° 58 distrayantes : - Le 27 mai, ils se sont rendus à st Quentin et plus précisément au musée du papillon où ils ont pu découvrir différents insectes et leur évolution. Ils ont fini la journée au parc d’Isle toujours à la découverte des insectes. - Le 9 juin, une intervenante est venue passer la journée dans la classe de Madame Dujour: Le matin il y a eu un récapitulatif sur la métamorphose de la chenille en papillon (sujet vu à la sortie de St Quentin). Ils ont ensuite appris au travers de jeux comment différencier un papillon de jour et un papillon de nuit. L'après-midi ils sont allés à la chasse aux papillons. Les petits ont pu attraper avec des filets divers insectes (libellules, araignées, papillons .....) qu'ils ont mis dans des boites transparentes pour les observer et les ont libérés par la suite. Les enfants ayant fait un élevage de papillons (ramenés de st Quentin) les ont relâchés également durant cette après-midi-là. -

Fiche De Randonnée

Lille N 2 Laonnois A 26 Balade à pied Laon A 1 A 4 microbalade ÀÀ l’ombrl’ombree N 2 Reims A 4 Durée : 0 h 45 desdes rremparempartsts PARIS Longueur : 2 km ▼ 106 m - ▲ 125 m COUCY-LE-CHÂTEAU – COUCY-LE-CHÂTEAU Balisage : jaune et vert Sur le plateau de Coucy, en éperon au-dessus du passage de la vallée Niveau : assez facile de l’Ailette à la vallée de l’Oise, se dressent les vestiges de ce qui fut la plus grande forteresse d’Europe. Ce petit circuit qui épouse le tracé Points forts : • Cœur historique des remparts offre une succession ininterrompue de points de vue de Coucy-le-Château. sur la campagne et la forêt environnantes. • Points de vue sur les vallées de l’Ailette et de l’Oise, Porte de Soissons panorama qu’en 4, ainsi et leurs versants boisés. D (office de tourisme). se restaurer : que sur Coucy-la-Ville et Descendre la côte de Sois- la forêt de St-Gobain). • Rendez-vous sur le site chemin faisant : sons sur 20 m (panorama internet pour accéder aux 4 Tourner à gauche vers sur la vallée de l'Ailette). offres associées à ce circuit. la Porte de Chauny. Pren- • Sur la commune de Coucy- Variante de D à 1 : face à Se loger dre à droite et descendre le-Château : ville fortifiée (rempart, château), église St-Sauveur (XII-XIIIe s.), l’office de tourisme, s'engager dans l'im- sur 100 m. À hauteur du troisième candé- gloriette (XVIIe s.), source couverte, passe St-Sauveur. -

Possibilities of Royal Power in the Late Carolingian Age: Charles III the Simple

Possibilities of royal power in the late Carolingian age: Charles III the Simple Summary The thesis aims to determine the possibilities of royal power in the late Carolingian age, analysing the reign of Charles III the Simple (893/898-923). His predecessors’ reigns up to the death of his grandfather Charles II the Bald (843-877) serve as basis for comparison, thus also allowing to identify mid-term developments in the political structures shaping the Frankish world toward the turn from the 9th to the 10th century. Royal power is understood to have derived from the interaction of the ruler with the nobles around him. Following the reading of modern scholarship, the latter are considered as partners of the former, participating in the royal decision-making process and at the same time acting as executors of these decisions, thus transmitting the royal power into the various parts of the realm. Hence, the question for the royal room for manoeuvre is a question of the relations between the ruler and the nobles around him. Accordingly, the analysis of these relations forms the core part of the study. Based on the royal diplomas, interpreted in the context of the narrative evidence, the noble networks in contact with the rulers are revealed and their influence examined. Thus, over the course of the reigns of Louis II the Stammerer (877-879) and his sons Louis III (879-882) and Carloman II (879-884) up until the rule of Charles III the Fat (884-888), the existence of first one, then two groups of nobles significantly influencing royal politics become visible. -

IAUP Baku 2018 Semi-Annual Meeting

IAUP Baku 2018 Semi-Annual Meeting “Globalization and New Dimensions in Higher Education” 18-20th April, 2018 Venue: Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers Website: https://iaupasoiu.meetinghand.com/en/#home CONFERENCE PROGRAMME WEDNESDAY 18th April 2018 Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers 18:30 Registration 1A, Mehdi Hüseyn Street Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers, 19:00-21:00 Opening Cocktail Party Uzeyir Hajibeyov Ballroom, 19:05 Welcome speech by IAUP President Mr. Kakha Shengelia 19:10 Welcome speech by Ministry of Education representative 19:30 Opening Speech by Rector of ASOIU Mustafa Babanli THURSDAY 19th April 2018 Visit to Alley of Honor, Martyrs' Lane Meeting Point: Foyer in Fairmont 09:00 - 09:45 Hotel 10:00 - 10:15 Mr. Kakha Shengelia Nizami Ganjavi A Grand Ballroom, IAUP President Fairmont Baku 10:15 - 10:30 Mr. Ceyhun Bayramov Deputy Minister of Education of the Republic of Azerbaijan 10:30-10:45 Mr. Mikheil Chkhenkeli Minister of Education and Science of Georgia 10:45 - 11:00 Prof. Mustafa Babanli Rector of Azerbaijan State Oil and Industry University 11:00 - 11:30 Coffee Break Keynote 1: Modern approach to knowledge transfer: interdisciplinary 11:30 - 12:00 studies and creative thinking Speaker: Prof. Philippe Turek University of Strasbourg 12:00 - 13:00 Panel discussion 1 13:00 - 14:00 Lunch 14:00 - 15:30 Networking meeting of rectors and presidents 14:00– 16:00 Floor Presentation of Azerbaijani Universities (parallel to the networking meeting) 18:30 - 19:00 Transfer from Farimont Hotel to Buta Palace Small Hall, Buta Palace 19:00 - 22:00 Gala -

Charlemagne Empire and Society

CHARLEMAGNE EMPIRE AND SOCIETY editedbyJoamta Story Manchester University Press Manchesterand New York disMhutcdexclusively in the USAby Polgrave Copyright ManchesterUniversity Press2005 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chaptersbelongs to their respectiveauthors, and no chapter may be reproducedwholly or in part without the expresspermission in writing of both author and publisher. Publishedby ManchesterUniversity Press Oxford Road,Manchester 8113 9\R. UK and Room 400,17S Fifth Avenue. New York NY 10010, USA www. m an chestcru niversi rvp ress.co. uk Distributedexclusively in the L)S.4 by Palgrave,175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010,USA Distributedexclusively in Canadaby UBC Press,University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, CanadaV6T 1Z? British Library Cataloguing"in-PublicationData A cataloguerecord for this book is available from the British Library Library of CongressCataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 7088 0 hardhuck EAN 978 0 7190 7088 4 ISBN 0 7190 7089 9 papaluck EAN 978 0 7190 7089 1 First published 2005 14 13 1211 100908070605 10987654321 Typeset in Dante with Trajan display by Koinonia, Manchester Printed in Great Britain by Bell & Bain Limited, Glasgow IN MEMORY OF DONALD A. BULLOUGH 1928-2002 AND TIMOTHY REUTER 1947-2002 13 CHARLEMAGNE'S COINAGE: IDEOLOGY AND ECONOMY SimonCoupland Introduction basis Was Charles the Great - Charlemagne - really great? On the of the numis- matic evidence, the answer is resoundingly positive. True, the transformation of the Frankish currency had already begun: the gold coinage of the Merovingian era had already been replaced by silver coins in Francia, and the pound had already been divided into 240 of these silver 'deniers' (denarii). -

Baku Airport Bristol Hotel, Vienna Corinthia Hotel Budapest Corinthia

Europe Baku Airport Baku Azerbaijan Bristol Hotel, Vienna Vienna Austria Corinthia Hotel Budapest Budapest Hungary Corinthia Nevskij Palace Hotel, St Petersburg St Petersburg Russia Fairmont Hotel Flame Towers Baku Azerbaijan Four Seasons Hotel Gresham Palace Budapest Hungary Grand Hotel Europe, St Petersburg St Petersburg Russia Grand Hotel Vienna Vienna Austria Hilton DoubleTree Zagreb Zagreb Croatia Hilton Hotel am Stadtpark, Vienna Vienna Austria Hilton Hotel Dusseldorf Dusseldorf Germany Hilton Milan Milan Italy Hotel Danieli Venice Venice Italy Hotel Palazzo Parigi Milan Italy Hotel Vier Jahreszieten Hamburg Hamburg Germany Hyatt Regency Belgrade Belgrade Serbia Hyatt Regenct Cologne Cologne Germany Hyatt Regency Mainz Mainz Germany Intercontinental Hotel Davos Davos Switzerland Kempinski Geneva Geneva Switzerland Marriott Aurora, Moscow Moscow Russia Marriott Courtyard, Pratteln Pratteln Switzerland Park Hyatt, Zurich Zurich Switzerland Radisson Royal Hotel Ukraine, Moscow Moscow Russia Sacher Hotel Vienna Vienna Austria Suvretta House Hotel, St Moritz St Moritz Switzerland Vals Kurhotel Vals Switzerland Waldorf Astoria Amsterdam Amsterdam Netherlands France Ascott Arc de Triomphe Paris France Balmoral Paris Paris France Casino de Monte Carlo Monte Carlo Monaco Dolce Fregate Saint-Cyr-sur-mer Saint-Cyr-sur-mer France Duc de Saint-Simon Paris France Four Seasons George V Paris France Fouquets Paris Hotel & Restaurants Paris France Hôtel de Paris Monaco Monaco Hôtel du Palais Biarritz France Hôtel Hermitage Monaco Monaco Monaco Hôtel -

Price and Mileage, Mically-Priced

i & PAGE TWO THE BROOKINGS REGISTER, BROOKINGS, S. D., THURSDAY. JULY 25. 191 S be appropriated to the public treas- against REPORT OF FAIR ance of Germans unable to check al- Italians keeping their pressure FINANCIAL ury through taxation." and CELEBRATION lies who moved forward half rnlle. Austrians both in Italian theater Mr. Hoover cites the business of Raid by Americans last night south- in Albania. In latter region consider- packers Weekly Summary of War News mighty efforts of Rex. the Chicago meat as a case west of Munster resulted penetration able ground gained along Devoli river. In spite of the Brief Account of Daily Happenings Brookings County lair in point. of German lines for 500 to 600 meters North of Marne Germans making Hargett, the following “There is an additional phase of the pleased to report the and captured prisoners. Raid preced- preparations for further retreat are by regulation receipts and dis- limitation of profits WEDNESDAY 11 while bound to Europe, navy de- ed by effective artillery preparation. Signs everywhere that Germans are figures, showing the Day’’ on July where such regulation needs co-ordi- partment advised by Vice Admiral Enemy suffered heavy casualties. destroying mateiiai and munitions in bursements at our “Gala nation with taxation,” says Mr. Hoov- Germans attack Allied lines vicious- Sims. Ten officers and men of crew Germans forced to withdraw from pocket to north of river Marne be- 4th, at our fair grounds: er. “If a regulation of profits or price missing. Rossignol wood, Rheims, prepara- Tickets sold $588.05 j ly on both sides of Rheims salient, of 92 between Hebuterne tween Soissons and to pictures.. -

Cc La Belle Judith 31

- 95 - Une reine du IXe siècle cc La belle Judith 31 Judith (< La Belle )> est la deuxikme épouse du roi Louis le Pieux, elle est la m6re du roi (Charles le Chauve. Née un peu apres 800, elle meurt en l’année 843. Pour évoquer la figure de cette reine, qui séjourna souvent A Laon, à Samoussy, à Quierzy, à Corbeny, à Ercry (St-Erme), à Trosly-Loire, à Savonnières, à Servais ou à Versigny, - laissons parler deux auteurs, ses contemporains. Ge premier est Sun poète : Ermold le Noir, connu polrr son long <( Pohe sur le roi Louis le Pieux >. Erincld est aquitain : son teint basané, ses cheveux noirs l’ont fait surnommer : <( Nigellus >) le Noir. Intimemient lie d’amitié avec Pépin, prince d’Aquitaine et deuxième fils de Louis le Pieux et de la reine Hermengarde, première femmfe du roi, Ermold est un homme d‘&lise qui a‘toujours vécu à la cotir des Carolingiens. C’est un courtisan qui s’est imprudemment mélé aux différends qui séparent le roi Louis, d*2 ses fils du premifer lit. Ayant intrigué pom Pépin, prince d’Aquitaine, Ermold est brusquement !exilé A Strasbourg en 826. Là, pour fléchir le courroux de son souverain, Ermold adresse à Louis un grand poème en quatre chants, où il implore son pardon, tout en cklébrant la gloire de l’empereur et de sa deuxième écouse Judith. Au cours de 2.650 vers, l’exilé évoque !e paradis perdu de la cour carolin- gienne ; ce paradis, qu’il pleure en exil, est, sous sa plume, un monde de beauté et de luxe, où évolue Jgditht la Belle, qu’il dbcrit avec mille prkcieux détails vécus. -

Revolt and the Manipulation of Sacral and Private Space in 12Th-Century Laon and Bruges

Power and culture : new perspectives on spatiality in european history / edited by Pieter François, Taina Syrjämaa, Henri Terho. - Pisa : Plus-Pisa university press, 2008. – (The- matic work group. 1, Power and culture ; 3) 110 (21.) 1. Spazio – Concetto 2. Europa – Cultura - Storia I. François, Pieter II. Syrjämaa, Taina III. Terho, Henri CIP a cura del Sistema bibliotecario dell’Università di Pisa This volume is published thanks to the support of the Directorate General for Research of the European Commission, by the Sixth Framework Network of Excellence CLIOHRES.net under the contract CIT3-CT-2005-006164. The volume is solely the responsibility of the Network and the authors; the European Community cannot be held responsible for its contents or for any use which may be made of it. Cover: Alberto Papafava, View of Piazza di Siena in Roma, watercolour, Palazzo Papafava, Padua. © 1990 Photo Scala, Florence © 2008 by CLIOHRES.net The materials published as part of the CLIOHRES Project are the property of the CLIOHRES.net Consortium. They are available for study and use, provided that the source is clearly acknowledged. [email protected] - www.cliohres.net Published by Edizioni Plus – Pisa University Press Lungarno Pacinotti, 43 56126 Pisa Tel. 050 2212056 – Fax 050 2212945 [email protected] www.edizioniplus.it - Section “Biblioteca” Member of ISBN: 978-88-8492-553-4 Linguistic Revision Rodney Dean Informatic Editing Răzvan Adrian Marinescu Revolt and the Manipulation of Sacral and Private Space in 12th-Century Laon and Bruges Jeroen Deploige Ghent University ABSTRACT Thanks to the highly original testimony of the Benedictine abbot Guibert of Nogent and the cleric Galbert of Bruges we are well informed about the communal revolt in Laon in 1112, where bishop Gaudry was killed, and on the brutal events in Flanders after the murder of count Charles the Good in the church of St Donatian in Bruges in 1127.