The Effects of Structural Deposition: a Theoretical Research Project for the Social Uses of Causewayed Enclosures in the British Isles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neolithic Report

RESEARCH DEPARTMENT REPORT SERIES no. 29-2011 ISSN 1749-8775 REVIEW OF ANIMAL REMAINS FROM THE NEOLITHIC AND EARLY BRONZE AGE OF SOUTHERN BRITAIN (4000 BC – 1500 BC) ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES REPORT Dale Serjeantson ARCHAEOLOGICAL SCIENCE Research Department Report Series 29-2011 REVIEW OF ANIMAL REMAINS FROM THE NEOLITHIC AND EARLY BRONZE AGE OF SOUTHERN BRITAIN (4000 BC – 1500 BC) Dale Serjeantson © English Heritage ISSN 1749-8775 The Research Department Report Series, incorporates reports from all the specialist teams within the English Heritage Research Department: Archaeological Science; Archaeological Archives; Historic Interiors Research and Conservation; Archaeological Projects; Aerial Survey and Investigation; Archaeological Survey and Investigation; Architectural Investigation; Imaging, Graphics and Survey; and the Survey of London. It replaces the former Centre for Archaeology Reports Series, the Archaeological Investigation Report Series, and the Architectural Investigation Report Series. Many of these are interim reports which make available the results of specialist investigations in advance of full publication. They are not usually subject to external refereeing, and their conclusions may sometimes have to be modified in the light of information not available at the time of the investigation. Where no final project report is available, readers are advised to consult the author before citing these reports in any publication. Opinions expressed in Research Department Reports are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of English Heritage. Requests for further hard copies, after the initial print run, can be made by emailing: [email protected]. or by writing to English Heritage, Fort Cumberland, Fort Cumberland Road, Eastney, Portsmouth PO4 9LD Please note that a charge will be made to cover printing and postage. -

Brighton & Hove

Archaeological Investigations Project 2002 Post-Determination & Non-Planning Related Projects South East Region BRIGHTON & HOVE 3/745 (E.53.K005) TQ 34000350 16 ROEDEAN CRESCENT Watching Brief 2002 Brighton and Hove Archaeological Field Unit Brighton : Brighton and Hove Archaeological Field Unit, 2002, 1p Work undertaken by: Brighton and Hove Archaeological Field Unit No features were observed and no archaeological finds were recovered. [Au] 3/746 (E.53.K006) TQ 33850340 34 THE CLIFF, ROEDEAN Watching Brief 2002 Brighton and Hove Archaeological Field Unit Brighton : Brighton and Hove Archaeological Field Unit, 2002, 1p Work undertaken by: Brighton and Hove Archaeological Field Unit No features were observed. An examination of the soil removed produced 2 white patinated flint flakes and a single sherd of Roman grey ware pottery. [Au] Archaeological periods represented: PR, RO 3/747 (E.53.K004) TQ 33900340 40 THE CLIFF, ROEDEAN Watching Briefs 2002 Brighton and Hove Archaeological Field Unit Brighton : Brighton and Hove Archaeological Field Unit, 2002, 1p Work undertaken by: Brighton and Hove Archaeological Field Unit No features observed and finds of 2 struck flint flakes. [Au] Archaeological periods represented: PR 3/748 (E.53.K007) TQ 33950340 47 THE CLIFF, ROEDEAN Watching Briefs 2002 Brighton and Hove Archaeological Field Unit Brighton : Brighton and Hove Archaeological Field Unit, 2002, 1p Work undertaken by: Brighton and Hove Archaeological Field Unit No features were observed. An examination of the soil removed produced 3 grey patinated flint flakes. [Au] Archaeological periods represented: PR 1 Archaeological Investigations Project 2002 Post-Determination & Non-Planning Related Projects South East Region 3/749 (E.53.F007) TV 30950400 6 SHIP STREET, BRIGHTON An Archaeological Watching Brief maintained on groundworks at 6 Ship Street, Brighton, East Sussex Greatorex, C Polegate : CG Archaeology, 2002, 34pp, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: CG Archaeology The development of a new hotel at the site prompted a watching brief. -

FINAL Sussex Wildlife Trust Response to City Plan Part Two Reg 19 Oct2020

Contact: Jess Price E-mail: [email protected] Date: 29 October 20 By email only planningpolicy@brighton -hove.gov.uk Brighton & Hove City Council’s Development Plan April 2020 - Proposed Submission City Plan Part Two The Sussex Wildlife Trust recognises the importance of a plan led system as opposed to a developer led process and supports Brighton & Hove City Council’s (BHCC) desire to produce part 2 of their City Plan. We hope that our comments to this Regulation 19 consultation are used constructively to make certain that the plan properly plans for the natural capital needed within the city and ensures that any development is truly sustainable. Please find attatched our response within BHCC’s word document response form. We have made comments in the following sections: Section A – Your details Section C – Representations on policies DM1 – DM46, SA7, SSA1 to SSA7 DM22 – support DM32 – support DM37 – objection DM38 – objection DM39 – support DM40 – support DM42 – support Special Area SA7 – objection SSA1 – objection Section D – H1 Housing Sites and Mixed Use Sites – Objection Section E – H2 Housing Sites – Urban Fringe – Objection We have also included an Appendix – Appendix A. The Sussex Wildlife Trust wishes to participate in any examination hearings sessions relevant to any sections of the City Plan Part Two that we have submitted objections to. We wish to discuss our objections formally with the Inspector and respond to any additional evidence presented by other respondents. Yours sincerely Jess Price Conservation Officer Sussex Wildlife Trust City Plan Part Two - Proposed Submission Response Form (7 September – 30 October 2020) Please Note Policies in the Proposed Submission City Plan Part Two were agreed at Full Council on 23 April 2020. -

RPM Collections Development Policy 2013 FINAL

Collections Development Policy 2013 Name of museum: The Royal Pavilion & Museums Name of governing body: Brighton & Hove City Council Date on which this policy was approved: Summer 2013 Date at which this policy is due for review: no later than Summer 2017 This 2013 revision replaces RPM Acquisition & Disposal Policy, written 2005, revised 2009 - 1 -1 1 Statement of purpose The Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove aims to inspire, illuminate and challenge its visitors and virtual users. It does this by caring for and interpreting its outstanding collections and historic sites to support discovery, enjoyment and learning. RPM has a vital role in the cultural, economic, education and social life of the city, and the health and well-being of its citizens. It celebrates the city and its communities, helping generate civic pride and develop a sense of cultural identity, as well as building respect and understanding of others. It is a cultural industry employing a wide range of creative experts including curators, conservators, decorative artists, designers, artists, makers, teachers, actors and writers. It is a major tourist attraction supporting the city’s visitor economy. It plays a role in the knowledge economy through research, creating and disseminating knowledge through exhibition, display, publication, public learning and event programmes. It also provides inspiration, influence and a stepping of point for creative production both locally, nationally and internationally. It operates in a digital world making collections and knowledge available on line and providing a platform for user generated content and debate. The Royal Pavilion & Museums (RPM), as part of Brighton & Hove City Council (BHCC) collects, rationalises and disposes of collections within the remit and guidelines set out in this Collections Development policy document, in line with the current Forward Plan and strategic aims of the organisation. -

The Early Neolithic Tor Enclosures of Southwest Britain

The Early Neolithic Tor Enclosures of Southwest Britain By Simon R. Davies A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of Ph.D. Funded by the AHRC. i University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Along with causewayed enclosures, the tor enclosures of Cornwall and Devon represent the earliest enclosure of large open spaces in Britain and are the earliest form of surviving non-funerary monument. Their importance is at least as great as that of causewayed enclosures, and it might be argued that their proposed associations with settlement, farming, industry, trade and warfare indicate that they could reveal more about the Early Neolithic than many causewayed enclosure sites. Yet, despite being recognised as Neolithic in date as early as the 1920s, they have been subject to a disproportionately small amount of work. Indeed, the southwest, Cornwall especially, is almost treated like another country by many of those studying the Early Neolithic of southern Britain. When mentioned, this region is more likely to be included in studies of Ireland and the Irish Sea zone than studies concerning England. -

Royal Pavilion & Museums Collection Development Policy 2018

Royal Pavilion & Museums Collection Development Policy 2018 Name of museum: Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove (RPM) Name of governing body: Brighton & Hove City Council Date on which this policy was approved by governing body: 17 January 2019 Policy review procedure: The collections development policy will be published and reviewed from time to time, at least once every five years. Date at which this policy is due for review: January 2024 Arts Council England will be notified of any changes to the collections development policy, and the implications of any such changes for the future of collections. 1. Relationship to other policies & plans of RPM 1.1 RPM’s mission: ‘Our mission is to use our unique collections, buildings and knowledge to connect people to the past and help them understand the present in order to positively influence their future.’ RPM is also guided by a manifesto which contains a number of key pledges that inform its acquisition and use of collections https://brightonmuseums.org.uk/manifesto 1.2 The governing body will ensure that both acquisition and disposal1 are carried out openly and with transparency. 1.3 By definition, RPM has a long-term purpose and holds collections in trust for the benefit of the public in relation to its stated objectives. The governing body therefore accepts the principle that sound curatorial reasons must be established before consideration is given to any acquisition to the collection, or the disposal of any items in RPM’s collection. 1.4 Acquisitions outside the current stated policy will only be made in exceptional circumstances. -

Thesis for the Ph.D. Degree Submitted to the University of London Faculty of Arts

Thesis for the Ph.D. Degree submitted to the University of London Faculty of Arts by Isobe]. Foster Smith, B.A. Institute of Archaeology. May 1956. THE DECORATIVE ART OF NEOLITHIC CERAMICS IN SOUTH-EASTERN ENGLAND AND ITS RELATIONS 8 1L ii. CONTENTS Abstract page v Acimowledgement s vii List of Text-figures viii. Part I. Introduction page 1. History of the subject, p.1; ii. Plan of the study, p.1; iii. The geographical area covered by the study, p.3; iv. Definition of the chronological period covered, p.4. Part II. The Wthdmill Hill Complex page '7 1. The distribution of Windmill Hill pottery in south-eastern England, p.8; ii. The pottery, p.15; Abingdon ware, p.16; Whitehawk ware, p.23; Lilderthall ware, p.29; Mixed groups, p.37; Other groups, p.41; 11.1. Artifacts associated with the pottery, p.43; iv. 'ode of occurrence, p.49; v. Economy, p.54; vi. Relative chronology, p.56; vii. Relationships with other Western Neolithic groups, p.59. Part III. The Peterborough Complex page 1. The distribution of Peterborogh ware in the south-eastern area, p.70; ii. he pottery, p.77; The Ebbsfleet style, p.78; The ortlake style, p.93; The Fengate style, p.104; iii. Other artifacts associated with Peterborough ware in the south-eastern area, p.11?; iv. vode of occurrence, p.124; v. Economy, p.137; vi. Relationships and dating, p.139; vii. The survival of the Peterborouh ceramic tradition, p.158; viii. The origins of the Peterborough complex, p.169. iii CONTENTS Part IV. -

Causewayed Enclosures and the Early Neolithic

South East Research Framework resource assessment seminar Causewayed enclosures and the Early Neolithic: the chronology and character of monument building and settlement in Kent, Surrey and Sussex in the early to mid-4th millennium cal BC Frances Healy Honorary Research Fellow, Cardiff University Causewayed enclosures This paper is concerned with the early and middle 4th millennium cal BC, the period occupied by the early Neolithic. Its starting point lies in the project Dating Causewayed Enclosures: towards a History of the Early Neolithic in Southern Britain , initiated at Cardiff University in 2003 by Professor Alasdair Whittle, and funded by The Arts and Humanities Research Council and English Heritage, whose Scientific Dating Co-Ordinator, Dr Alex Bayliss, has been responsible for obtaining more than 400 new radiocarbon dates and modelling them with an equal number of others from 42 causewayed and related enclosures in England, Wales and Ireland (Whittle et al. 2008; Bayliss et al. forthcoming; Whittle et al. in prep.). These enclosures, characteristically defined by ditches interrupted by gaps (or causeways) have long been seen as defining features of the early Neolithic in southern Britain. This is largely due to their large size compared with other earthworks of the period, to their often rich cultural assemblages and to the stratified sequences which they provide. They consist of single or multiple circuits and other lengths of interrupted ditch, sometimes with surviving banks, and range in area from over 8 ha to less than 1 ha. They saw varied and sometimes rich deposits of human bone, food remains, digging implements, artefacts and the debris of their manufacture. -

Whitehawk Hill Local Nature Reserve Results of Public Consultation 2012

Whitehawk Hill Local Nature Reserve Results of Public Consultation 2012 Whitehawk Hill has an ancient history, with a 6000 year old Neolithic camp and old chalk grassland, which supports many rare plant and animal species. Today the hill is a vital green lung within the city and is a popular area for dog walking and nature spotting. The council is looking at ways to conserve the important features of the hill and improve it as a resource for local people. The Consultation People in the local area were asked to comment on how they’d like to see the hill managed in the future. We received around three hundred responses from all over the city, and beyond. This is very encouraging and clearly shows how highly regarded the hill is, and for so many reasons. Here’s a reminder of the Council’s seven priorities for the future of Whitehawk Hill: Wildlife – Conserve, restore and enhance the rare and important species and habitats. Recreation – Promote quiet, informal access for all. Communities – Encourage community involvement and awareness Landscape – Protect the hill and promote awareness of the importance of the hill within the South Downs History – Safeguard the nationally important Neolithic camp on the hill and raise its profile. Food – Provide more allotment plots and support community-led food projects. Problems – Minimise anti-social behaviour on the hill, such as fly-tipping, fires, motorcycling and dog related issues. Question 1: Do you agree with the Council’s 7 priorities for the future of Whitehawk Hill? Yes 86% No 9% Don’t know 5% Comments: "I'm very supportive of all seven priorities. -

Model Landscapes: on the Use of GIS in Archaeology – Part Two

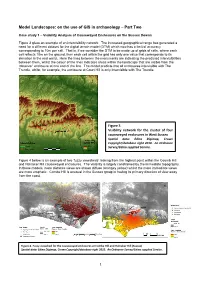

Model Landscapes: on the use of GIS in archaeology – Part Two Case study 1 – Visibility Analysis of Causewayed Enclosures on the Sussex Downs Figure 3 gives an example of an intervisibility network. The increased geographical range has generated a need for a different dataset for the digital terrain model (DTM) which now has a limit of accuracy corresponding to 10m per cell. That is, if we consider the DTM to be made up of grids of cells, where each cell reflects 10m on the ground, then each cell within the grid has only one value that corresponds to its elevation in the real world. Here the lines between the monuments are indicating the predicted intervisibilities between them, whilst the colour of the lines indicates areas within the landscape that are visible from the ‘observer’ enclosure at one end of the line. The model predicts that all enclosures intervisible with The Trundle, whilst, for example, the enclosure at Court Hill is only intervisible with The Trundle. Figure 3. Visibility network for the cluster of four causewayed enclosures in West Sussex Spatial data: Edina Digimap, Crown Copyright/database right 2010. An Ordnance Survey/Edina supplied Service. Figure 4 below is an example of two ‘fuzzy viewsheds’ looking from the highest point within the Coomb Hill and Halnaker Hill causewayed enclosures. The visibility is largely constrained by the immediate topography. In these models, more distance views are shown diffuse (orangey yellow) whilst the more immediate views are more emphatic. Combe Hill is unusual in the Sussex group in having its primary direction of view away from the coast. -

Report Thirty-Second Congress Earthworks Committee

Congress of Archaeological Societies in union with The Society of Antiquaries of London Report of the Thirty-second Congress and of the Earthworks Committee for the year 1924 Price i/- London Published by the Congress of Archaeological Societies and printed by Percy Lund, Humphries & Co., Ltd., 3, Amen Corner, London, E.C-4. Congress of Archaeological Societies in union with the Society of Antiquaries of London. OFFICERS AND COUNCIL. President : The President of the Society of Antiquaries : THE EARL OF CRAWFORD AND BALCARRES, K.T., LL.D., F.R.S. Hon. Treasurer : W. J. HEMP, F.S.A. Hon. Secretary : H. S. KlNGSFORD, M.A. Society of Antiquaries, Burlington House, W.i. Other Members of Council : O. G. S. CRAWFORD, B.A., F.S.A.1 WILLIAM MARTIN, M.A., LL.D., MRS. CUNNINGTON. 1 F.S.A. 2 MAJOR W. J. FREER, D.L., J.P., R. E. M. WHEELER, M.C., D.Lit., F.S.A. 1 F.S.A.2 WlLLOUGHBY GARDNER, F.S.A. 1 VERY REV. THE DEAN OF E. THURLOW LEEDS, M.A., F.S.A. 1 GLOUCESTER, D.D., F.S.A.3 J. P. WILLIAMS-FREEMAN, M.D. 1 H. JENKINSON, M.A., F.S.A. 3 E. A. B. BARNARD, F.S.A. 2 W. PAGE, F.S.A. 3 REV. G. M. BENTON, F.S.A. 2 H. PEAKE, F.S.A. 3 J. E. COUCHMAN, F.S.A. 2 G. McN. RUSHFORTH, M.A. F.S.A." CYRIL Fox, Ph.D., F.S.A. 2 PROF. A. HAMILTON THOMPSON, D.Lit., F.S.A. -

A Report on the Outcomes of the Whitehawk Community Archaeology Project, Including a Post-Excavation Assessment and Updated Project Design

WHITEHAWK CAMP, MANOR HILL, BRIGHTON, EAST SUSSEX NGR: 532938 104787 (TQ 32938 04787) Scheduled Ancient Monument: 1010929 A REPORT ON THE OUTCOMES OF THE WHITEHAWK COMMUNITY ARCHAEOLOGY PROJECT, INCLUDING A POST-EXCAVATION ASSESSMENT AND UPDATED PROJECT DESIGN ASE Project No: P106 Site Code: WHC14 ASE Report No: 2015222 OASIS ID: By Jon Sygrave With contributions by Luke Barber, Trista Clifford, Anna Doherty, Hayley Forsyth, Karine Le Hégarat, Andy Maxted, Dawn Elise Mooney, Hilary Orange, Dr Paola Ponce, Don Richardson Illustrations by Justin Russell November 2016 Abstract This report presents the results of the Whitehawk Camp Community Archaeology Project carried out by the Whitehawk Camp Partnership between April 2014 and July 2015. The work was generously funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund. This report details the background to the project, the methodology by which it was undertaken, the results of the archaeological fieldwork, the reassessment of the archive material, the potential and significance of the archaeological results, presents a new research agenda for the site and outlines the scope of potential future projects. This report does not detail all the project outcomes and the reader is directed to Appendix 5: An Evaluation Report to the Heritage Lottery Fund on the Outcomes of the Whitehawk Camp Community Archaeology Project (Orange et al 2015) for a summary of the main results of the Project including how successful it was in engaging with target audiences, what changes to heritage, community and people the project has brought about, project legacy and future work. The 2014-5 excavations, targeted on anomalies identified in the preceding geophysical survey (ASE 2014b), encountered a small number of features and a large unstratified finds assemblage associated with allotment gardens, the dumping of refuse and activity probably related to Brighton Racecourse dating to the 19th- 21st centuries.