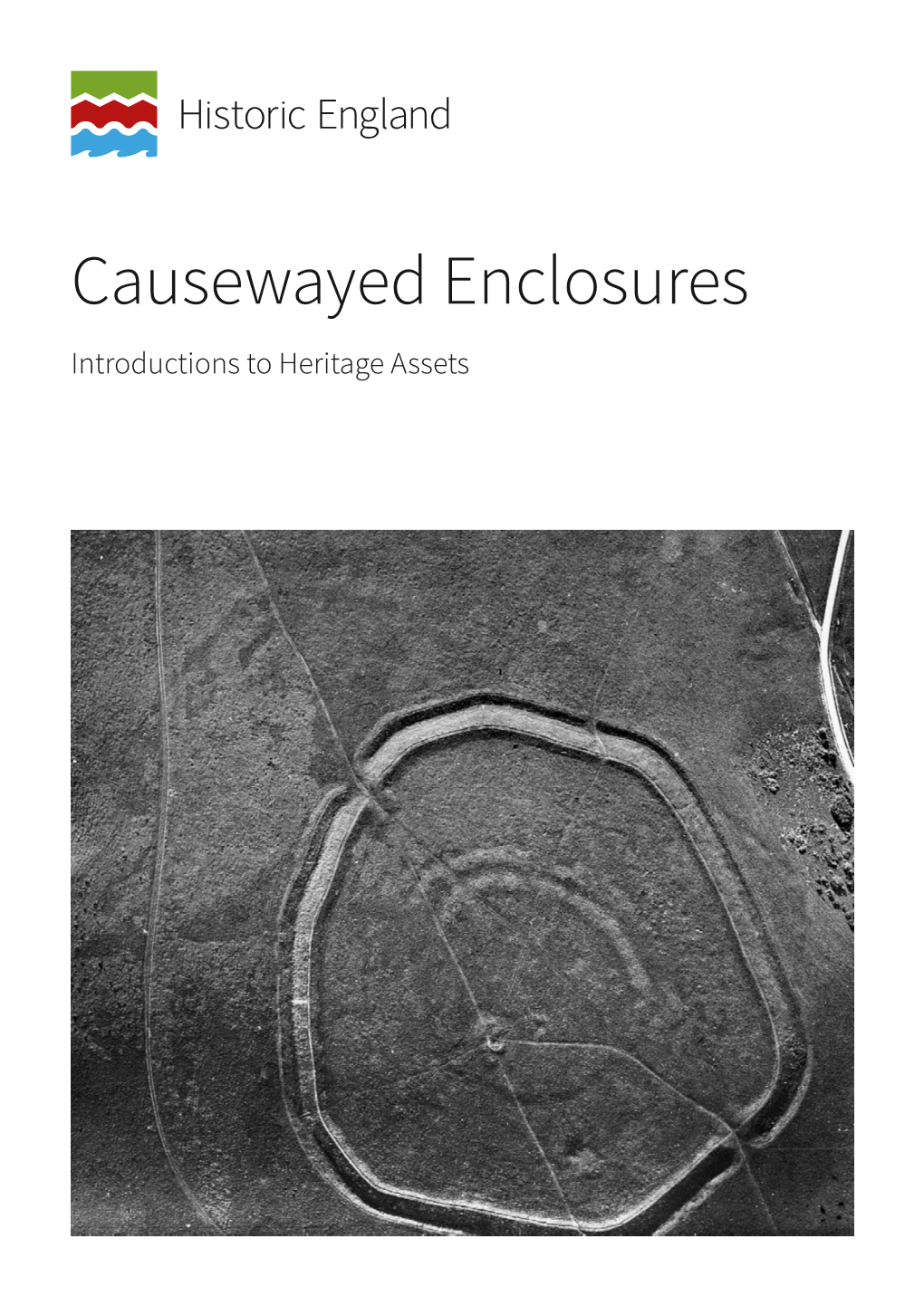

Causewayed Enclosures Introductions to Heritage Assets Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Division 31: Earthworks

FACILITIES MANAGEMENT – DESIGN & CONSTRUCTION EDITION: APRIL 29, 2020 4202 E. FOWLER AVENUE, OPM 100 | TAMPA, FLORIDA 33620-7550 PHONE: (813) 974-2845 | WEBSITE: usf.edu/fm-dc DESIGN & CONSTRUCTION GUIDELINES DIVISION 31 EARTHWORKS DIVISION 31 EARTHWORK SECTION 31 05 00 EARTHWORK ............................................................................................................ 2 SECTION 31 10 00 SITE CLEARING ........................................................................................................ 5 SECTION 31 60 00 FOUNDATION ............................................................................................................ 6 DIVISION 31 EARTHWORKS PAGE 1 OF 7 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION GUIDELINES SECTION 31 05 00 EARTHWORK 1.1 SITE GRADING A. Rough Grading: Slopes shall not be steeper than one (1) vertical to five (5) horizontal in general open lawn and other grassed areas. Steeper slopes will be permitted only on a case-by-case basis where special need warrants. Tops and bottoms of banks and other break points shall be rounded to provide smooth and graceful transitions. In areas of walks without ramps, slopes shall not be steeper than one (1) vertical to twenty (20) horizontal. Ensure ramped areas comply with the requirements of the Americans with Disability Act (ADA) and Florida Accessibility Code, and meet the intent of the FBC, Chapter 468. B. Finish Grading: This operation shall consist of the final dressing to provide a uniform layer of the topsoil and/or nutrients required -

The University of Bradford Institutional Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bradford Scholars The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Where available access to the published online version may require a subscription. Author(s): Gibson, Alex M. Title: An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Publication year: 2012 Book title: Enclosing the Neolithic : Recent studies in Britain and Ireland. Report No: BAR International Series 2440. Publisher: Archaeopress. Link to publisher’s site: http://www.archaeopress.com/archaeopressshop/public/defaultAll.asp?QuickSear ch=2440 Citation: Gibson, A. (2012). An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? In: Gibson, A. (ed.). Enclosing the Neolithic: Recent studies in Britain and Europe. Oxford: Archaeopress. BAR International Series 2440, pp. 1-20. Copyright statement: © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2012. An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Alex Gibson Abstract This paper summarises 80 years of ‘henge’ studies. It considers the range of monuments originally considered henges and how more diverse sites became added to the original list. It examines the diversity of monuments considered to be henges, their origins, their associated monument types and their dates. Since the introduction of the term, archaeologists have often been uncomfortable with it. -

Friday, the 19Th of June 09:00 Garcia Sanjuan, Leonardo the Hole in the Doughnut

monumental landscapes neolithic subsistence and megaliths 09:25 schiesberg, sara; zimmermann, andreas 10:40 coffee break siemens lecture hall bosch conference room Stages and Cycles: The Demography of Populations Practicing 11:00 schiesberg, sara Collective Burials Theories, Methods and Results The Bone Puzzle. Reconstructing Burial Rites in Collective Tombs 09:00 schmitt, felicitas; bartelheim, martin; bueno ramírez, primitiva 09:00 o’connell, michael 09:50 rinne, christoph; fuchs, katharina; kopp, juliane; 11:25 cummings, vicki Just passing by? Investigating in the Territory of the Megalith Builders The pollen evidence for early prehistoric farming impact: towards a better schade-lindig, sabine; susat, julian; krause-kyora, ben The social implications of construction: a consideration of the earliest of the Southern European Plains. The Case of Azután, Toledo. understanding of the archaeological fi eld evidence for Neolithic activity in Niedertiefenbach reloaded: The builders of the Wartberg gallery grave Neolithic monuments of Britain and Ireland 09:25 carrero pazos, miguel; rodríguez casal, antón a. western Ireland 10:15 klingner, susan; schultz, michael 11:50 pollard, joshua Neolithic Territory and Funeral Megalithic Space in Galicia (Nw. Of 09:25 diers, sarah; fritsch, barbara The physical strain on megalithic tomb builders from northern How routine life was made sacred: settlement and monumentality in Iberian Peninsula): A Synthetic Approach Changing environments in a Megalithic Landscape: the Altmark case Germany –results of an -

Corrosion Evaluation of Mechanically Stabilized Earth Walls

Research Report KTC-05-28/SPR 239-02-1F KENTUCKY TRANSPORTATION CENTER College of Engineering CORROSION EVALUATION OF MECHANICALLY STABILIZED EARTH WALLS Our Mission We provide services to the transportation community through research, technology transfer and education. We create and participate in partnerships to promote safe and effective transportation systems. We Value... Teamwork -- Listening and Communicating, Along with Courtesy and Respect for Others Honesty and Ethical Behavior Delivering the Highest Quality Products and Services Continuous Improvement in All That We Do For more information or a complete publication list, contact us KENTUCKY TRANSPORTATION CENTER 176 Raymond Building University of Kentucky Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0281 (859) 257-4513 (859) 257-1815 (FAX) 1-800-432-0719 www.ktc.uky.edu [email protected] The University of Kentucky is an Equal Opportunity Organization Research Report KTC-05-28/SPR – 239-02-1F Corrosion Evaluation of Mechanically Stabilized Earth Walls Research Report KTC-05-28/SPR – 239-02-1F Corrosion Evaluation of Mechanically Stabilized Earth Walls By Tony L. Beckham Leicheng Sun Tommy C. Hopkins Research Geologist Research Engineer Program Manager Kentucky Transportation Center College of Engineering University of Kentucky in cooperation with the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet The Commonwealth of Kentucky and Federal Highway Administration The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the University of Kentucky, Kentucky Transportation Cabinet, nor the Federal Highway Administration. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. -

Tunnels & Earthworks (Cuts & Embankments) of the Comarnic

Tender Designs of Major Infrastructure Highway Projects Tunnels & Earthworks (Cuts & Embankments) of the Comarnic – Brasov Motorway Romania Project Tunnels, cuts and embankments of the Comarnic – Brasov Motorway, Romania. Construction Cost Total Cost: approx. €. 1.5bn. Project Schdlhedule Tender Design: 2013 Construction: 2014 - Project Description • Sinaia, Busteni & Predeal Twin Bore Highway Tunnels Sinaia length: 5.890m Busteni length: 6.200m Predeal length: 7.500m Excavation cross section: 84m2 -132m2 Effective cross section: 66m2 -81m2 Excavation Method NATM – Mechanical excavation, drilling and blasting Final Lining Reinforced concrete • Highway Cuts and Embankments (Section from Typical tunnels cross section Ch. 110+600-168+600) Embankments: Ltotal = 26.0km Cuts: Ltotal = 11.0km Geology • Alluvial deposits, limestones, flysch, marbles, schist and conglomerates • Groundwater • Max. overburden at the tunnels: 195m – 340m Our Services Tender design and preparation of the technical offer on behalf of ViStrAda Nord Typical embankment cross section Client ViStrada Nord Consortium (VINCI S.A. - VINCI Construction Grand Projects S.A.S. - VINCI Construction Terrassement S.A.S. – STRABAG A.G. - STRABAG S.E. – AKTOR Concessions S.A. - AKTOR S.A.) 4, Thalias Str. & 109, Kimis Ave., P.C. 151 22, Maroussi, Athens Tel.: + 30 210 6837490, + 30 210 6897040, + 30 210 6835858 Fax: + 30 210 6837499, e-mail: [email protected], www.omikronkappa.gr Railway Project Consulting services, technical review and checking of designs and Panagopoula Railway Tunnel associated detailed designs Athens - Patras High Speed Railway Line, Section Rododafni – Psathopirgos Greece Project • Consulting services, technical review and checking of the designs of the project: “Construction of the New Double High Speed Railway Line at the section Rododafni – Psathopirgos from CH. -

Failure of Slopes and Embankments Under Static and Seismic Loading

American Scientific Research Journal for Engineering, Technology, and Sciences (ASRJETS) ISSN (Print) 2313-4410, ISSN (Online) 2313-4402 © Global Society of Scientific Research and Researchers http://asrjetsjournal.org/ Failure of Slopes and Embankments Under Static and Seismic Loading Nicolaos Alamanis* Lecturer, Dept. of Civil Engineering, Technological Educational Institute of Thessaly, Larissa, Greece, Civil engineer (National Technical University of Athens, D.E.A Ecole Centrale Paris) Email: [email protected] Summary The stability of slopes and embankments under the influence of static and seismic loads has been the subject of study for many researchers. This paper presents the mechanisms and causes of landslides as well as the forms of failure of slopes and embankments under static and seismic loading, with examples of failures from both Greek and international space. There is also mention to measures to protect and stabilize landslides, categories of slope stability analysis, and methods of seismic impact analysis. What follows is the determination of tolerable movements based on the caused damage on natural slopes, dams and embankments and an attempt is made to connect them with the vulnerability curves that are one of the key elements of stochastic seismic hazard. Particular importance is given to the statistical parameters of the mechanical characteristics of the sloping soil mass and to the simulation of random fields necessary for solving complex geotechnical works. Finally, we compare the simulation and description of random fields and the L.A.S. method is observed to be the most accurate of all simulation methods. The L.A.S. algorithm in conjunction with finite difference models can demonstrate the large fluctuations in the factor of safety values and the permanent seismic displacements of the slopes under the effect of seismic charges whose time histories are known. -

How to Tell a Cromlech from a Quoit ©

How to tell a cromlech from a quoit © As you might have guessed from the title, this article looks at different types of Neolithic or early Bronze Age megaliths and burial mounds, with particular reference to some well-known examples in the UK. It’s also a quick overview of some of the terms used when describing certain types of megaliths, standing stones and tombs. The definitions below serve to illustrate that there is little general agreement over what we could classify as burial mounds. Burial mounds, cairns, tumuli and barrows can all refer to man- made hills of earth or stone, are located globally and may include all types of standing stones. A barrow is a mound of earth that covers a burial. Sometimes, burials were dug into the original ground surface, but some are found placed in the mound itself. The term, barrow, can be used for British burial mounds of any period. However, round barrows can be dated to either the Early Bronze Age or the Saxon period before the conversion to Christianity, whereas long barrows are usually Neolithic in origin. So, what is a megalith? A megalith is a large stone structure or a group of standing stones - the term, megalith means great stone, from two Greek words, megas (meaning: great) and lithos (meaning: stone). However, the general meaning of megaliths includes any structure composed of large stones, which include tombs and circular standing structures. Such structures have been found in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North and South America and may have had religious significance. Megaliths tend to be put into two general categories, ie dolmens or menhirs. -

2008 WDOAM Magazine – Autumn

WEALD & DOWNLAND OPEN AIR MUSEUM Autumn 2008 Enjoy the Museum this winter TheThe mysterymystery ofof thethe Events & Courses househouse from Walderton 2008-09 LookingLooking aheadahead –– WorkingWorking WoodyardWoodyard thethe nextnext fivefive yearsyears getsgets underwayunderway £1.00 where sold CONTENTS Museum plans 19th century 5 Gonville Cottage to wo more farmsteads are planned their social and chronological character- become a museum Tfor the Museum site in the istics. When Tindalls cottage is exhibit future to complement the 16th complete the Museum will display a century Bayleaf steading, a 17th cen- house or cottage from each century, 7 New hop display tury one based around Pendean from Hangleton cottage (13th century) farmhouse and a new proposal – a to Whittaker’s cottages (mid-19th 19th century ‘Georgian’ farmstead. century), representing various social 9 The house from The proposal is contained in the levels, including landless labourers, Walderton, West Sussex Museum’s new five-year plan (2008- husbandmen and yeoman farmers. 2012), which also includes provision for Putting more emphasis on chronol- 17 Obituaries a new development plan proposing sites ogy, the Museum intends to pursue for the remaining exhibits in storage another series, that of farmsteads. At 18 New plan will inform (some 15 buildings). present there is one, Bayleaf (16th activity in West Dean The plan was written by Museum century) but there are appropriate Park Director Richard Harris, following a buildings in store to create a second five-month process of discussion and at Pendean (17th century). A third consultation with staff and volunteers, farmstead representing the early 19th 21 Events Diary 2008-09 led by Museum Chairman, Paul Rigg. -

View Characterisation and Analysis

South Downs National Park: View Characterisation and Analysis Final Report Prepared by LUC on behalf of the South Downs National Park Authority November 2015 Project Title: 6298 SDNP View Characterisation and Analysis Client: South Downs National Park Authority Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by Director V1 12/8/15 Draft report R Knight, R R Knight K Ahern Swann V2 9/9/15 Final report R Knight, R R Knight K Ahern Swann V3 4/11/15 Minor changes to final R Knight, R R Knight K Ahern report Swann South Downs National Park: View Characterisation and Analysis Final Report Prepared by LUC on behalf of the South Downs National Park Authority November 2015 Planning & EIA LUC LONDON Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Registered in England Design 43 Chalton Street London Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning London Bristol Registered Office: Landscape Management NW1 1JD Glasgow 43 Chalton Street Ecology T +44 (0)20 7383 5784 Edinburgh London NW1 1JD Mapping & Visualisation [email protected] FS 566056 EMS 566057 LUC uses 100% recycled paper LUC BRISTOL 12th Floor Colston Tower Colston Street Bristol BS1 4XE T +44 (0)117 929 1997 [email protected] LUC GLASGOW 37 Otago Street Glasgow G12 8JJ T +44 (0)141 334 9595 [email protected] LUC EDINBURGH 28 Stafford Street Edinburgh EH3 7BD T +44 (0)131 202 1616 [email protected] Contents 1 Introduction 1 Background to the study 1 Aims and purpose 1 Outputs and uses 1 2 View patterns, representative views and visual sensitivity 4 Introduction 4 View -

Settlement Hierarchy and Social Change in Southern Britain in the Iron Age

SETTLEMENT HIERARCHY AND SOCIAL CHANGE IN SOUTHERN BRITAIN IN THE IRON AGE BARRY CUNLIFFE The paper explores aspects of the social and economie development of southern Britain in the pre-Roman Iron Age. A distinct territoriality can be recognized in some areas extending over many centuries. A major distinction can be made between the Central Southern area, dominated by strongly defended hillforts, and the Eastern area where hillforts are rare. It is argued that these contrasts, which reflect differences in socio-economic structure, may have been caused by population pressures in the centre south. Contrasts with north western Europe are noted and reference is made to further changes caused by the advance of Rome. Introduction North western zone The last two decades has seen an intensification Northern zone in the study of the Iron Age in southern Britain. South western zone Until the early 1960s most excavation effort had been focussed on the chaiklands of Wessex, but Central southern zone recent programmes of fieid-wori< and excava Eastern zone tion in the South Midlands (in particuiar Oxfordshire and Northamptonshire) and in East Angiia (the Fen margin and Essex) have begun to redress the Wessex-centred balance of our discussions while at the same time emphasizing the social and economie difference between eastern England (broadly the tcrritory depen- dent upon the rivers tlowing into the southern part of the North Sea) and the central southern are which surrounds it (i.e. Wessex, the Cots- wolds and the Welsh Borderland. It is upon these two broad regions that our discussions below wil! be centred. -

The Medway Valley Prehistoric Landscapes Project

AST NUMBER 72 November 2012 THE NEWSLETTER OF THE PREHISTORIC SOCIETY Registered Office University College London, Institute of Archaeology, 31–34 Gordon Square, London WC1H 0PY http://www.prehistoricsociety.org/ PTHE MEDWAY VALLEY PREHISTORIC LANDSCAPES PROJECT The Early Neolithic megalithic monuments of the Medway valley in Kent have a long history of speculative antiquarian and archaeological enquiry. Their widely-assumed importance for understanding the earliest agricultural societies in Britain, despite how little is really known about them, probably stems from the fact that they represent the south-easternmost group of megalithic sites in the British Isles and have figured - usually in passing - in most accounts of Neolithic monumentality since Stukeley drew Kit’s Coty House in 1722. Remarkably, this distinctive group of monuments and other major sites (such as Burham causewayed enclosure) have not previously been subject to a Kit’s Coty House: integrated laser scan and ground-penetrating landscape-scale programme of investigation, while the radar survey of the east end of the monument only significant excavation of a megalithic site in the region took place over 50 years ago (by Alexander at the The Medway Valley Project aims to establish a new Chestnuts in 1957). The relative neglect of the area, and interpretative framework for the Neolithic archaeology its research potential, have been thrown into sharper of the Medway valley, focusing on the architectural relief recently by the discovery of two Early Neolithic forms, chronologies and use-histories of monuments, long halls nearby at White Horse Stone/Pilgrim’s Way and changes in environment and inhabitation during the on the High Speed 1 route, and by the radiocarbon period c. -

Henges in Yorkshire

Looking south across the Thornborough Henges. SE2879/116 NMR17991/01 20/5/04. ©English Heritage. NMR Prehistoric Monuments in the A1 Corridor Information and activities for teachers, group leaders and young archaeologists about the henges, cursus, barrows and other monuments in this area Between Ferrybridge and Catterick the modern A1 carries more than 50,000 vehicles a day through West and North Yorkshire. It passes close to a number of significant but often overlooked monuments that are up to 6,000 years old. The earliest of these are the long, narrow enclosures known as cursus. These were followed by massive ditched and banked enclosures called henges and then smaller monuments, including round barrows. The A1 also passes by Iron Age settlements and Roman towns, forts and villas. This map shows the route of the A1 in Yorkshire and North of Boroughbridge the A1 the major prehistoric monuments that lie close by. follows Dere Street Roman road. Please be aware that the monuments featured in this booklet may lie on privately-owned land. 1 The Landscape Setting of the A1 Road Neolithic and Bronze Age Monuments Between Boroughbridge and Cursus monuments are very long larger fields A1 Road quarries Catterick the A1 heads north with rectangular enclosures, typically more the Pennines to the west and than 1km long. They are thought to the low lying vales of York and date from the middle to late Neolithic Mowbray to the east. This area period and were probably used for has a rural feel with a few larger ceremonies and rituals. settlements (like the cathedral city of Ripon and the market town of The western end of the Thornborough pockets of woodland cursus is rounded but some are square.