Rethinking the Future of Northern Australia's Regions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Internal Migration Estimates, Provisional, March 2021

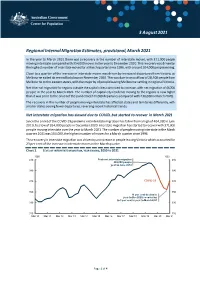

3 August 2021 Regional Internal Migration Estimates, provisional, March 2021 In the year to March 2021 there was a recovery in the number of interstate moves, with 371,000 people moving interstate compared with 354,000 moves in the year to December 2020. This recovery was driven by the highest number of interstate moves for a March quarter since 1996, with around 104,000 people moving. Close to a quarter of the increase in interstate moves was driven by increased departures from Victoria, as Melbourne exited its second lockdown in November 2020. This was due to an outflow of 28,500 people from Melbourne to the eastern states, with the majority of people leaving Melbourne settling in regional Victoria. Net internal migration for regions outside the capital cities continued to increase, with net migration of 44,700 people in the year to March 2021. The number of capital city residents moving to the regions is now higher than it was prior to the onset of the pandemic (244,000 departures compared with 230,000 in March 2020). The recovery in the number of people moving interstate has affected states and territories differently, with smaller states seeing fewer departures, reversing recent historical trends. Net interstate migration has slowed due to COVID, but started to recover in March 2021 Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic net interstate migration has fallen from a high of 404,000 in June 2019, to a low of 354,000 people in December 2020. Interstate migration has started to recover with 371,000 people moving interstate over the year to March 2021. -

Returning to the Returning to the Northern Territory

Population Studies Group POPULATION STUDIES School for Social and Policy Research Charles Darwin University RESEARCH BRIEF Northern Territory 0909 ISSUE Number 2008004 [email protected] School for Social and Policy Research 2008 RETURNING TO THE NNNORTHERNNORTHERN TERRITORY KEY FINDINGS RESEARCH AIM • Although some out-migrants may be lost to To identify the the Northern Territory altogether, the characteristics of people who return to the telephone survey showed that 30% of Northern Territory respondents had left and returned to the after a period of absence Territory at least once. and the reasons fforororor • Return migration is often planned from the their return outset and can occur, for example, at the completion of fixed-term employment, medical treatment, study, travel or undertaking family commitments This Research Brief draws on data from the elsewhere. Territory Mobility • Return migration may be for a limited time Survey and in-depth with 23% of telephone survey respondents interviews conducted as saying they planned to leave again with two part of the Northern or three years. Territory Mobility Project. Funding for • Retaining a family home in the Territory the research was provides an emotional connection which may provided by an ARC encourage return migration. Linkage Grant. • Climate, suitable housing and existing social networks may encourage return migration of older ex-Territory residents. • For many years, the Northern Territory has This Research Brief been a destination to which people return. was prepared by What can be done to encourage people to Elizabeth CreedCreed. return and to extend the period of time they plan to spend in the Territory? POPULATION STUDIES GROUP RESEARCH BRIEF ISSUE 2008004: RETURNING TO THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Background Consistently high rates of population turnover in the Northern Territory result in annual gains and losses of significant numbers of residents. -

Soils of the Northern Territory Factsheet

Soils of the Northern Territory | factsheet Soils are developed over thousands of years and are made up of air, water, minerals, organic material and microorganisms. They can take on a wide variety of characteristics and form ecosystems which support all life on earth. In the NT, soils are an important natural resource for land-based agricultural industries. These industries and the soils that they depend on are a major contributor to the Northern Territory economy and need to be managed sustainably. Common Soils in the Northern Territory Kandosols Tenosols Hydrosols Often referred to as red, These weakly developed or sandy These seasonally inundated yellow and brown earths, soils are important for horticulture in soils support both high value these massive and earthy the Ali Curung and Alice Springs conservation areas important soils are important for regions. They soils show some for ecotourism as well as the agricultural and horticultural degree of development (minor pastoral industry. They production. They occur colour or soil texture increase in generally occur in higher throughout the NT and are subsoil) down the profile. They rainfall areas on coastal widespread across the Top include sandplains, granitic soils floodplains, swamps and End, Sturt plateau, Tennant and the sand dunes of beach ridges drainage lines. They also Creek and Central Australian and deserts. include soils in mangroves and regions. salt flats. Darwin sandy Katherine loamy Red Alice Springs Coastal floodplain Red Kandosol Kandosol sandplainTenosol Hydrosol Rudosols Chromosols These are very shallow soils or those with minimal These are soils with an abrupt increase in clay soil development. Rudosols include very shallow content below the top soil. -

Australia's Northern Territory: the First Jurisdiction to Legislate Voluntary Euthanasia, and the First to Repeal It

DePaul Journal of Health Care Law Volume 1 Issue 3 Spring 1997: Symposium - Physician- Article 8 Assisted Suicide November 2015 Australia's Northern Territory: The First Jurisdiction to Legislate Voluntary Euthanasia, and the First to Repeal It Andrew L. Plattner Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jhcl Recommended Citation Andrew L. Plattner, Australia's Northern Territory: The First Jurisdiction to Legislate Voluntary Euthanasia, and the First to Repeal It, 1 DePaul J. Health Care L. 645 (1997) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jhcl/vol1/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Health Care Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AUSTRALIA'S NORTHERN TERRITORY: THE FIRST JURISDICTION TO LEGISLATE VOLUNTARY EUTHANASIA, AND THE FIRST TO REPEAL IT AndreivL. Plattner INTRODUCTION On May 25, 1995, the legislature for the Northern Territory of Australia enacted the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act,' [hereinafter referred to as the Act] which becane effective on July 1, 1996.2 However, in less than a year, on March 25, 1997, the Act was repealed by the Australian National Assembly.3 Australia's Northern Territory for a brief time was the only place in the world where specific legislation gave terminally ill patients the right to seek assistance from a physician in order to hasten a patient's death.4 This Article provides a historical account of Australia's Rights of the Terminally Ill Act, evaluates the factors leading to the Act's repeal, and explores the effect of the once-recognized right to assisted suicide in Australia. -

European Discovery and South Australian Administration of the Northern Territory

3 Prior to 1911: European discovery and South Australian administration of the Northern Territory The first of five time periods that will be used to structure this account of the development and deployment of vocational education and training in the Northern Territory covers the era when European explorers initially intruded upon the ancient Aboriginal tribal lands and culminates with the colony of South Australia gaining control of the jurisdiction. Great Britain took possession of the northern Australian coastline in 1824 when Captain Bremer declared this section of the continent as part of New South Wales. While there were several abortive attempts to establish settlements along the tropical north coast, the climate and isolation provided insurmountable difficulties for the would-be residents. Similarly, the arid southern portion of this territory proved to be inhospitable and difficult to settle. As part of an ongoing project of establishing the borders of the Australian colonies, the Northern Territory became physically separated from New South Wales when the Colonial Office of Great Britain gave control of the jurisdiction to the Government of the Colony of South Australia in 1863 (The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia 1974, p. 83) following the first non-Indigenous south to north crossing of the continent by the South Australian-based explorer John McDouall Stuart in the previous year. 35 VocatioNAL EducatioN ANd TRAiNiNg On the political front, in 1888 South Australia designated the Northern Territory as a single electoral district returning two members to its Legislative Assembly and gave representation in the Upper House in Adelaide. Full adult suffrage was extended by South Australia to all Northern Territory white residents in 1890 that demonstrated an explicit and purposeful disenfranchisement of the much more numerous Asian and Aboriginal populations. -

Population Growth with Future Declines in Indigenous Fertility and Mortality, Suggest Aging of the NT Population Will Continue Strongly in the Coming Decades

Please find attached: 1 Executive summary 2. Current Indigenous housing needs – discussion points 3. The Territory’s Problem of Access to Service Delivery 4. Northern Territory Population Policy Copies of powerpoint slides Northern Territory Population (Tony Barnes – NT Treasury) Mortality in the Northern Territory (Part 1: All Cause Mortality) The NT Labour Market – Impacts of an ageing Australian workforce Education in the Northern Territory Integrated approaches in Indigenous communities COAG meeting 25 June NT Revenue Unfunded superannuation Attachments (available on request) Northern Territory Position Paper – Indigenous Housing 2004/05 and beyond A Report to Thamarrurr Regional Council December 2003 — Baseline Profiles for Social and Economic Development Planning in the Thamarrurr Region Department of Employment, Education and Training — Impacts of an ageing Australian workforce The Northern Territory Economy – Economic Performance Spreadsheets in xls form showing ABS Census Data on Indigenous communities in the NT at a disaggragated level. Productivity Commission Inquiry into the Fiscal and Economic Effects of Ageing Northern Territory Government Agencies’ submissions Executive Summary All the submissions to the PC concentrated upon the uniqueness of the Northern Territory. This had, and will have into the future, a number of impacts that belie the effect of a seemingly low proportion of aged persons in the Territory population. Treasury: Northern Territory Demography Presented the following unique features of the NT population: - • The NT population has a very different age distribution to the Australian population (see graph below), with more children, young adults and fewer old people. However, the NT’s population has been aging just as fast as the national population in terms of average age. -

Section 15 References

Section 15 References Trans Territory Pipeline Project Draft EIS Chapter 15 References 15. References ACIL Tasman, (2004). Economic Impact Assessment of the Trans Territory Pipeline. Prepared for Alcan Engineering Pty Ltd, March 2004. AGO Australian Greenhouse Office, (2002). Australian Methodology for the Estimation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks 2002. In: Energy (Fugitive Fuel Emissions). Australian Greenhouse Office, May 2004. AGO Australian Greenhouse Office, (2004a). Australian Greenhouse Office Factors and Methods Workbook, Version 4. Government of Australia, Canberra, August 2004. AGO Australian Greenhouse Office, (2004b). National Greenhouse Gas Inventory 2002. Australian Greenhouse Office, Canberra. April 2004. Available online from: http://www.greenhouse.gov.au/inventory/2002/pubs/inventory2002parta.pdf. AGSNT Australia Geological Survey Organisation Northern Territory, (1972). Ferguson River 1:250,000 Scale Geological Map 1972. Sheet SD 21-12 Second edition. AGSNT Australia Geological Survey Organisation Northern Territory, (1971). Katherine 1:250,000 Scale Geological Map 1994. Sheet SD 53-9. AGSNT Australia Geological Survey Organisation Northern Territory, (1964). Urapunga 1:250,000 Scale Geological Map 1964. Sheet SD 53-10. AGSNT Australia Geological Survey Organisation Northern Territory, (1999). Mount Marumba 1:250,000 ScaleGeological Map 1999. Sheet SD 53-6. AGSNT Australia Geological Survey Organisation Northern Territory, (1998). Blue Mud Bay 1:250,000 Scale Geological Map 1998. Sheet SD 53-7. AGSNT Australia Geological Survey Organisation Northern Territory, (1998). Arnhem Bay Gove 1:250,000 Scale Geological Map 1998. Sheet SD 53-3,4. AGSNT Australia Geological Survey Organisation Northern Territory, (1971). Port Keats 1:250,000 Scale Geological Map 1971. Alcan Gove, (2004a). EHS Policy. Available online from: http://www.alcangove.com.au/home/content.asp?PageID=310 [Accessed 30 Sept 2004]. -

Australian States and Territories Suicide Data 2019 (ABS, 2020)

Australian states and territories suicide data 2019 (ABS, 2020) Released, 23 October 2020 Notes about this summary: Victorian data ─ Care needs to be taken when interpreting data derived from Victorian coroner-referred deaths including suicide (Victorian and national mortality datasets). ─ In the first quarter of 2020, the ABS and the Victorian Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages (RBDM) undertook a joint investigation aimed at identifying death registrations that had not been submitted to the ABS as part of usual processing procedures. ─ This investigation identified 2,812 deaths that had been registered in 2017, 2018 and 2019, but had not previously been provided to the ABS. These deaths were not reported because of an issue associated with the Registry's previous processing system which was replaced in early 2019. ─ The ABS has made a permanent time series adjustment to statistics for suicide deaths. The additional death registrations for 2017 and 2018 have been placed back in their respective registration years. ─ This time series change is associated with an administrative processing issue rather than a true change in the prevalence of suicide deaths. Australian Capital Territory suicide data 2019 (ABS, 2020) Number of deaths ACT, 53 NT, 50 TAS, 108 Australian Capital Territory in 2019 ‒ 53 people died by suicide in the Australian SA, 251 Capital Territory (41 male, 12 female), which is an increase on the 47 recorded in 2018. NSW, 937 ‒ The Australian Capital Territory was the WA, 418 second lowest state/territory after the Northern Territory. ‒ The number of suicide deaths was highest in New South Wales (937), followed by VIC, 717 QLD, 784 Queensland (784), and Victoria (717). -

SLENDER-BILLED THORNBILL (Western Subspecies) Acanthiza Iredalei Iradalei

Threatened Species of the Northern Territory SLENDER-BILLED THORNBILL (western subspecies) Acanthiza iredalei iradalei Conservation status Australia: Vulnerable Northern Territory: Extinct Photo: G. Chapman Description The slender-billed thornbill is a small bird, with head and body length of 9-10 cm. The upperparts are light olive-grey to dark olive-brown. The rump and base of tail are buff-yellow to yellow-olive. The forehead and cheeks are scalloped and flecked pale to deep cream. The underparts are uniformly cream-white to cream-buff. The bill is dark and the eye pale. Distribution The slender-billed thornbill is endemic to Australia and occurs as three subspecies Known locations of the slender-billed thornbill across the semi-arid regions of the southern half of the continent from the Carnarvon Conservation reserves where reported: bioregion in Western Australia to the South None. Australia-Victoria border. Only one subspecies has been recorded for the Ecology Northern Territory (NT). The slender-billed thornbill occurs in In the NT, the slender-billed thornbill is shrubland, typically in areas of saltmarsh known from a single specimen collected by S. dominated by samphire, bluebush (Maireana) A. White on the lower Finke River on or saltbush (Atriplex) around salt lakes or low Idracowra Station on 21 August 1913 (Storr heath on sandplain (Schodde and Tidemann 1977). There have been no records of the 1986; Schodde and Mason 1999). It feeds on species in the NT since this time. A potential invertebrates, mostly insects and spiders, that sighting from Barrow Creek in 1942 was it captures amongst the foliage of shrubs. -

History and Heritage

History and Heritage The Territory’s history The legendary journeys of John The Territory has played a significant McDouall Stuart, one of Australia’s role in the ongoing journey of of ancient and enduring most intrepid explorers, led the first reconciliation with Aboriginal peoples Aboriginal culture, successful expedition to traverse in Australia. The `Wave Hill walk-off’, intrepid explorers, the Australian mainland from south where Gurindji Aboriginal stockmen to north. This journey saw the demanded fair wages for their work courageous pioneering epic construction of the Overland is one of the most symbolic historical women and men, and Telegraph Line in the 1870s, described events for Aboriginal peoples, which wartime battles is as ’Australia’s greatest engineering led to the birth of Aboriginal land feat of the nineteenth century’ rights. unlike any other across and the first direct communication Australia. From the Top between Australia and Britain. The For military heritage, the Top End is End to the Red Centre stories of pastoralists and the Gold unparalleled being Australia’s only Rush days of Pine Creek attest to the location of major battle during World the stories of the people fact that the Territory has narrative War II. Darwin felt the full force of who have shaped the that embodies the pioneering the war with air raids by aircraft of Territory underpin our spirit. From driving routes, heritage the Imperial Japanese Navy in 1942, sites and museums, there are many wreaking destruction on the city. distinctive sense of place opportunities to relive the footsteps and unique identity. of the early explorers and pioneers. -

19. Liberty Square

19. Liberty Square Liberty Square was named by the Darwin Town Council in June 1919 to commemorate the ‘Darwin Rebellion’ of 17 December 1918. That rebellion, which culminated in a protest directed at Government House by hundreds of workers on this site, and the unrest leading to it, resulted in a 1919 Royal Commission into the Administration of the Northern Territory conducted by Justice Norman Kirkwood Ewing (1870-1928). On the western side of Liberty Square is a memorial cairn at the place where the sub-sea cable from Banjowangie (Banyuwangi) Indonesia was joined with the Overland Telegraph Line to revolutionise communications in Australia on 20 November 1871. Towards the eastern side is a plinth and plaque commemorating the scientific achievement of Pietro ‘Commendatore’ Baracchi who, in collaboration with colleagues in Singapore and Banjowangie, established true longitude of Port Darwin and other Australian colonial and New Zealand capital cities in 1883 in the grounds of the Port Darwin Post Office and Telegraphic Station (now Parliament House). On the eastern side near the Supreme Court is a Banyan tree, which is valued by the community as a remnant of the original Darwin foreshore vegetation. It is over 200 years old and was the congregation point for Larrakia youths prior to ceremonies that took place under the nearby Tamarind tree. Liberty Square was the site for the original Darwin Cenotaph, which is now located on the old Darwin Oval on the Esplanade. History Sub-sea Telegraph Cables From the 1850s telegraph technology was very quickly taken up by the Australian colonies, building networks across their own territories, and then soon connecting to each other. -

South Australia & Northern Territory

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd South Australia & Northern Territory Darwin & the Top End (p142) Uluru & Outback Northern Territory (p179) Outback South Australia (p129) Western South Australia (p120) Barossa Valley & Southeastern South Australia Adelaide (p99) & Around (p52) Anthony Ham & Charles Rawlings-Way PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to ADELAIDE & Barmera & Around . .. 111 SA & NT . 4 AROUND . 52 Loxton . 112 SA & NT Map . 6 Adelaide . 53 Berri . 113 SA & NT’s Top 12 . .. 8 Adelaide Hills . 76 Renmark & Paringa . 113 Need to Know . 16 Hahndorf . 77 Limestone Coast . 114 First Time . .18 Stirling Area . 78 Robe . 115 Meningie & If You Like . 20 Gumeracha, Birdwood & Lobethal . 80 Coorong National Park . 116 Month by Month . 24 Mt Barker . 81 Mount Gambier . 117 Itineraries . 28 Fleurieu Peninsula . 81 Penola & the Coonawarra Wine Region . 119 South Australian McLaren Vale . 81 Wine & Food . 33 Willunga . 83 Your Outback Trip . 38 Gulf St Vincent Beaches . 84 WESTERN Travel with Children . 47 Victor Harbor . 86 SOUTH AUSTRALIA 120 Regions at a Glance . 49 Port Elliot . 87 Yorke Peninsula . 121 Goolwa . 88 West Coast . 121 Kangaroo Island . 89 East Coast . 122 MATT MUNRO/LONELY PLANET © PLANET MUNRO/LONELY MATT Penneshaw & South Coast & Dudley Peninsula . 92 Innes National Park . 122 American River . 93 Eyre Peninsula & the West Coast . 124 Kingscote . .. 94 Port Augusta . 124 North Coast Road . 95 Port Lincoln . 125 South Coast Road . 96 Coffin Bay . 127 Flinders Chase National Park . 97 Streaky Bay & Around . 127 Ceduna . 128 BAROSSA VALLEY & Ceduna to the Western SOUTHEASTERN Australia Border . 128 ALICE SPRINGS P196 SOUTH AUSTRALIA 99 Barossa Valley . 102 OUTBACK Tanunda .