Pest Risk Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

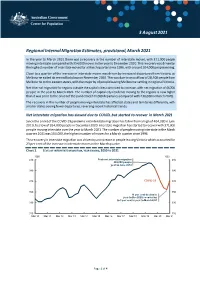

Regional Internal Migration Estimates, Provisional, March 2021

3 August 2021 Regional Internal Migration Estimates, provisional, March 2021 In the year to March 2021 there was a recovery in the number of interstate moves, with 371,000 people moving interstate compared with 354,000 moves in the year to December 2020. This recovery was driven by the highest number of interstate moves for a March quarter since 1996, with around 104,000 people moving. Close to a quarter of the increase in interstate moves was driven by increased departures from Victoria, as Melbourne exited its second lockdown in November 2020. This was due to an outflow of 28,500 people from Melbourne to the eastern states, with the majority of people leaving Melbourne settling in regional Victoria. Net internal migration for regions outside the capital cities continued to increase, with net migration of 44,700 people in the year to March 2021. The number of capital city residents moving to the regions is now higher than it was prior to the onset of the pandemic (244,000 departures compared with 230,000 in March 2020). The recovery in the number of people moving interstate has affected states and territories differently, with smaller states seeing fewer departures, reversing recent historical trends. Net interstate migration has slowed due to COVID, but started to recover in March 2021 Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic net interstate migration has fallen from a high of 404,000 in June 2019, to a low of 354,000 people in December 2020. Interstate migration has started to recover with 371,000 people moving interstate over the year to March 2021. -

Black Swans, Or the Limits of Statistical Modelling

Black swans, or the limits of statistical modelling Eric Marsden <[email protected]> Do I follow indicators that could tell me when my models may be wrong? On the 1001st day, a little before Thanksgiving, the turkey has a surprise. A turkey is fed for 1000 days. Each passing day confirms to its statistics department that the human race cares about its welfare “with increased statistical significance”. 2 / 58 A turkey is fed for 1000 days. Each passing day confirms to its statistics department that the human race cares about its welfare “with increased statistical significance”. On the 1001st day, a little before Thanksgiving, the turkey has a surprise. 2 / 58 Things that have never happened before, happen all the time. — Scott D. Sagan, The Limits of Safety: Organizations, ‘‘ Accidents, And Nuclear Weapons, 1993 In risk analysis, these are called “unexampled events” or “outliers” or “black swans”. 3 / 58 The term “black swan” was used in16th century discussions of impossibility (all swans known to Europeans were white). Explorers arriving in Australia discovered a species of swan that is black. The term is now used to refer to events that occur though they had been thought to be impossible. 4 / 58 Black swans ▷ Characteristics of a black swan event: • an outlier • lies outside the realm of regular expectations • nothing in the past can convincingly point to its possibility • carries an extreme impact ▷ Note that: • in spite of its outlier status, it is often easy to produce an explanation for the event after the fact • a black swan event may be a surprise for some, but not for others; it’s a subjective, knowledge-dependent notion • warnings about the event may have been ignored because of strong personal and organizational resistance to changing beliefs and procedures Source: The Black Swan: the Impact of the Highly Improbable, N. -

Birding Oxley Creek Common Brisbane, Australia

Birding Oxley Creek Common Brisbane, Australia Hugh Possingham and Mat Gilfedder – January 2011 [email protected] www.ecology.uq.edu.au 3379 9388 (h) Other photos, records and comments contributed by: Cathy Gilfedder, Mike Bennett, David Niland, Mark Roberts, Pete Kyne, Conrad Hoskin, Chris Sanderson, Angela Wardell-Johnson, Denis Mollison. This guide provides information about the birds, and how to bird on, Oxley Creek Common. This is a public park (access restricted to the yellow parts of the map, page 6). Over 185 species have been recorded on Oxley Creek Common in the last 83 years, making it one of the best birding spots in Brisbane. This guide is complimented by a full annotated list of the species seen in, or from, the Common. How to get there Oxley Creek Common is in the suburb of Rocklea and is well signposted from Sherwood Road. If approaching from the east (Ipswich Road side), pass the Rocklea Markets and turn left before the bridge crossing Oxley Creek. If approaching from the west (Sherwood side) turn right about 100 m after the bridge over Oxley Creek. The gate is always open. Amenities The main development at Oxley Creek Common is the Red Shed, which is beside the car park (plenty of space). The Red Shed has toilets (composting), water, covered seating, and BBQ facilities. The toilets close about 8pm and open very early. The paths are flat, wide and easy to walk or cycle. When to arrive The diversity of waterbirds is a feature of the Common and these can be good at any time of the day. -

Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Sources Cited Alder, L. P. 1963. The calls and displays of African and In Bellrose, F. C. 1976. Ducks, geese and swans of North dian pygmy geese. In Wildfowl Trust, 14th Annual America. 2d ed. Harrisburg, Pa.: Stackpole. Report, pp. 174-75. Bellrose, F. c., & Hawkins, A. S. 1947. Duck weights in Il Ali, S. 1960. The pink-headed duck Rhodonessa caryo linois. Auk 64:422-30. phyllacea (Latham). Wildfowl Trust, 11th Annual Re Bengtson, S. A. 1966a. [Observation on the sexual be port, pp. 55-60. havior of the common scoter, Melanitta nigra, on the Ali, S., & Ripley, D. 1968. Handbook of the birds of India breeding grounds, with special reference to courting and Pakistan, together with those of Nepal, Sikkim, parties.] Var Fagelvarld 25:202-26. -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

Returning to the Returning to the Northern Territory

Population Studies Group POPULATION STUDIES School for Social and Policy Research Charles Darwin University RESEARCH BRIEF Northern Territory 0909 ISSUE Number 2008004 [email protected] School for Social and Policy Research 2008 RETURNING TO THE NNNORTHERNNORTHERN TERRITORY KEY FINDINGS RESEARCH AIM • Although some out-migrants may be lost to To identify the the Northern Territory altogether, the characteristics of people who return to the telephone survey showed that 30% of Northern Territory respondents had left and returned to the after a period of absence Territory at least once. and the reasons fforororor • Return migration is often planned from the their return outset and can occur, for example, at the completion of fixed-term employment, medical treatment, study, travel or undertaking family commitments This Research Brief draws on data from the elsewhere. Territory Mobility • Return migration may be for a limited time Survey and in-depth with 23% of telephone survey respondents interviews conducted as saying they planned to leave again with two part of the Northern or three years. Territory Mobility Project. Funding for • Retaining a family home in the Territory the research was provides an emotional connection which may provided by an ARC encourage return migration. Linkage Grant. • Climate, suitable housing and existing social networks may encourage return migration of older ex-Territory residents. • For many years, the Northern Territory has This Research Brief been a destination to which people return. was prepared by What can be done to encourage people to Elizabeth CreedCreed. return and to extend the period of time they plan to spend in the Territory? POPULATION STUDIES GROUP RESEARCH BRIEF ISSUE 2008004: RETURNING TO THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Background Consistently high rates of population turnover in the Northern Territory result in annual gains and losses of significant numbers of residents. -

ON 23(4) 555-567.Pdf

ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 23: 555–567, 2012 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY AND PAIR BEHAVIOR DURING INCUBATION OF THE BLACK-NECKED SWAN (CYGNUS MELANOCORYPHUS) Carmen Paz Silva1, Roberto Pablo Schlatter2 & Mauricio Soto-Gamboa1 1Instituto de Ciencias Ambientales y Evolutivas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Austral de Chile, Valdivia, Chile. E-mail: [email protected] 2Instituto de Ciencias Marinas y Limnológicas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Austral de Chile, Valdivia, Chile. Resumen. – Biología reproductiva y comportamiento del Cisne de Cuello Negro (Cygnus melano- coryphus). – El cisne de cuello negro (Cygnus melanocoryphus) es la única especie del género Cygnus que habita en Sudamérica. Si bien, el resto de las especies del género han sido extensamente estudia- das, para C. melanocoryphus aún no se ha descrito la mayor parte de su biología reproductiva. En este estudio evaluamos el comienzo y extensión de la temporada reproductiva, y el tamaño de nidada utili- zando datos recolectados en el Santuario Carlos Anwandter (SCA), Valdivia, Chile; correspondientes a 18 temporadas reproductivas. Por otro lado, estudiamos el comportamiento de las parejas durante el periodo de incubación, durante una temporada reproductiva. Se estimó el presupuesto de tiempo y dis- tancia con respecto al nido en seis parejas nidificantes. El periodo de nidificación se puede extender desde junio a enero y está influenciado por el tamaño de la población reproductiva y las condiciones cli- máticas. El tamaño de nidada se mantiene constante con una moda de tres huevos (promedio 3.13 ± 0.017; n = 5897). Ambos miembros de la pareja desarrollan actividades de vigilancia y mantención del nido, sin embargo, la incubación es una tarea exclusiva de la hembra, mientras que la defensa activa del nido es realizada por el macho. -

Soils of the Northern Territory Factsheet

Soils of the Northern Territory | factsheet Soils are developed over thousands of years and are made up of air, water, minerals, organic material and microorganisms. They can take on a wide variety of characteristics and form ecosystems which support all life on earth. In the NT, soils are an important natural resource for land-based agricultural industries. These industries and the soils that they depend on are a major contributor to the Northern Territory economy and need to be managed sustainably. Common Soils in the Northern Territory Kandosols Tenosols Hydrosols Often referred to as red, These weakly developed or sandy These seasonally inundated yellow and brown earths, soils are important for horticulture in soils support both high value these massive and earthy the Ali Curung and Alice Springs conservation areas important soils are important for regions. They soils show some for ecotourism as well as the agricultural and horticultural degree of development (minor pastoral industry. They production. They occur colour or soil texture increase in generally occur in higher throughout the NT and are subsoil) down the profile. They rainfall areas on coastal widespread across the Top include sandplains, granitic soils floodplains, swamps and End, Sturt plateau, Tennant and the sand dunes of beach ridges drainage lines. They also Creek and Central Australian and deserts. include soils in mangroves and regions. salt flats. Darwin sandy Katherine loamy Red Alice Springs Coastal floodplain Red Kandosol Kandosol sandplainTenosol Hydrosol Rudosols Chromosols These are very shallow soils or those with minimal These are soils with an abrupt increase in clay soil development. Rudosols include very shallow content below the top soil. -

Australia's Northern Territory: the First Jurisdiction to Legislate Voluntary Euthanasia, and the First to Repeal It

DePaul Journal of Health Care Law Volume 1 Issue 3 Spring 1997: Symposium - Physician- Article 8 Assisted Suicide November 2015 Australia's Northern Territory: The First Jurisdiction to Legislate Voluntary Euthanasia, and the First to Repeal It Andrew L. Plattner Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jhcl Recommended Citation Andrew L. Plattner, Australia's Northern Territory: The First Jurisdiction to Legislate Voluntary Euthanasia, and the First to Repeal It, 1 DePaul J. Health Care L. 645 (1997) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jhcl/vol1/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Health Care Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AUSTRALIA'S NORTHERN TERRITORY: THE FIRST JURISDICTION TO LEGISLATE VOLUNTARY EUTHANASIA, AND THE FIRST TO REPEAL IT AndreivL. Plattner INTRODUCTION On May 25, 1995, the legislature for the Northern Territory of Australia enacted the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act,' [hereinafter referred to as the Act] which becane effective on July 1, 1996.2 However, in less than a year, on March 25, 1997, the Act was repealed by the Australian National Assembly.3 Australia's Northern Territory for a brief time was the only place in the world where specific legislation gave terminally ill patients the right to seek assistance from a physician in order to hasten a patient's death.4 This Article provides a historical account of Australia's Rights of the Terminally Ill Act, evaluates the factors leading to the Act's repeal, and explores the effect of the once-recognized right to assisted suicide in Australia. -

Breeding Biology of the Magpie Goose

BREEDING BIOLOGY OF THE MAGPIE GOOSE Paul A. Johnsgard Summary A B r e e d in g pair of Magpie Geese was studied at the Wildfowl Trust during one breeding season and part of a second. Nest-building was performed by both sexes and was done in the typical anatid fashion of passing material back over the shoulders. Nests were built on land of sticks and green vegetation. Two copulations were observed, both of which occurred on the nest, and precopulatory as well as postcopulatory behaviour appears to differ greatly from the typical anatid patterns. Eggs were laid at approximate day-and-a-half intervals, and the nest was guarded by both sexes. Incubation was also performed by both sexes, with the male normally sitting during the night. A simple nest-relief ceremony is present. The eggs hatched after 28 to 30 days, and the goslings left the nest the morning after hatching. Unlike all other Anatidae so far studied, the goslings, in addition to foraging independently, are fed directly by their parents and a special whistling begging call associated with a gaping posture is present. It is suggested that the bright bill colouration and unusual cinnamon-coloured heads of downy Magpie Geese are also related to this parental feeding. The parents constructed a “ brood nest ” of herbaceous vegetation that the goslings rested and slept on, which is also unique among the Anatidae. Family bonds are strong, and a rudimentary form of “ triumph ceremony ” is present. Development of the young and moulting sequences of downy, juvenal, and immature plumages are described ; the presence of separate juvenal and immature plumages which are distinct from the adult plumage is apparently unique. -

European Discovery and South Australian Administration of the Northern Territory

3 Prior to 1911: European discovery and South Australian administration of the Northern Territory The first of five time periods that will be used to structure this account of the development and deployment of vocational education and training in the Northern Territory covers the era when European explorers initially intruded upon the ancient Aboriginal tribal lands and culminates with the colony of South Australia gaining control of the jurisdiction. Great Britain took possession of the northern Australian coastline in 1824 when Captain Bremer declared this section of the continent as part of New South Wales. While there were several abortive attempts to establish settlements along the tropical north coast, the climate and isolation provided insurmountable difficulties for the would-be residents. Similarly, the arid southern portion of this territory proved to be inhospitable and difficult to settle. As part of an ongoing project of establishing the borders of the Australian colonies, the Northern Territory became physically separated from New South Wales when the Colonial Office of Great Britain gave control of the jurisdiction to the Government of the Colony of South Australia in 1863 (The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia 1974, p. 83) following the first non-Indigenous south to north crossing of the continent by the South Australian-based explorer John McDouall Stuart in the previous year. 35 VocatioNAL EducatioN ANd TRAiNiNg On the political front, in 1888 South Australia designated the Northern Territory as a single electoral district returning two members to its Legislative Assembly and gave representation in the Upper House in Adelaide. Full adult suffrage was extended by South Australia to all Northern Territory white residents in 1890 that demonstrated an explicit and purposeful disenfranchisement of the much more numerous Asian and Aboriginal populations. -

Wildlife Management Program for the Magpie Goose (Anseranas Semipalmata) in the Northern Territory of Australia 2020-2030 Consultation Draft

Wildlife Management Program for the Magpie Goose (Anseranas semipalmata) in the Northern Territory of Australia 2020-2030 Consultation Draft www.denr.nt.gov.au/magpiegoose Wildlife Management Program for the Magpie Goose (Anseranas Document title semipalmata) in the Northern Territory of Australia 2020-2030 Department of Department of Environment and Natural Resources Environment and Po Box 496, Palmerston NT 0831 Natural Resources Telephone 08 8995 5099 Email: [email protected] Web: www.denr.nt.gov.au Approved by Date approved Document review 5 years or earlier as required TRM number BD2019/0017 Version Date Author Changes made 1.0 27 September 2019 Tim Clancy Format version 1 Acronyms / Full form / Definitions Terms Aboriginal Harvest carried out by Aboriginal people in accordance with Section 122 of the traditional harvest Territory Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1976. B Billion CDU Charles Darwin University CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species DENR Department of Environment and Natural Resources DPIR Department of Primary Industry and Resources DTSC Department of Tourism, Sport and Culture EPBC Act Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 IUCN The International Union for Conservation of Nature K Carrying capacity or maximum population the habitat can sustain when conditions close to optimal NAIWB National Avian Influenza Wild Bird Steering Group NLC Northern Land Council Non-Aboriginal Harvest carried out by either Aboriginal or non-Aboriginal people in accordance harvest with