European Discovery and South Australian Administration of the Northern Territory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

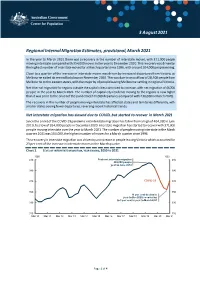

Regional Internal Migration Estimates, Provisional, March 2021

3 August 2021 Regional Internal Migration Estimates, provisional, March 2021 In the year to March 2021 there was a recovery in the number of interstate moves, with 371,000 people moving interstate compared with 354,000 moves in the year to December 2020. This recovery was driven by the highest number of interstate moves for a March quarter since 1996, with around 104,000 people moving. Close to a quarter of the increase in interstate moves was driven by increased departures from Victoria, as Melbourne exited its second lockdown in November 2020. This was due to an outflow of 28,500 people from Melbourne to the eastern states, with the majority of people leaving Melbourne settling in regional Victoria. Net internal migration for regions outside the capital cities continued to increase, with net migration of 44,700 people in the year to March 2021. The number of capital city residents moving to the regions is now higher than it was prior to the onset of the pandemic (244,000 departures compared with 230,000 in March 2020). The recovery in the number of people moving interstate has affected states and territories differently, with smaller states seeing fewer departures, reversing recent historical trends. Net interstate migration has slowed due to COVID, but started to recover in March 2021 Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic net interstate migration has fallen from a high of 404,000 in June 2019, to a low of 354,000 people in December 2020. Interstate migration has started to recover with 371,000 people moving interstate over the year to March 2021. -

The Nature of Northern Australia

THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects 1 (Inside cover) Lotus Flowers, Blue Lagoon, Lakefield National Park, Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 2 Northern Quoll. Photo by Lochman Transparencies 3 Sammy Walker, elder of Tirralintji, Kimberley. Photo by Sarah Legge 2 3 4 Recreational fisherman with 4 barramundi, Gulf Country. Photo by Larissa Cordner 5 Tourists in Zebidee Springs, Kimberley. Photo by Barry Traill 5 6 Dr Tommy George, Laura, 6 7 Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 7 Cattle mustering, Mornington Station, Kimberley. Photo by Alex Dudley ii THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects AUTHORS John Woinarski, Brendan Mackey, Henry Nix & Barry Traill PROJECT COORDINATED BY Larelle McMillan & Barry Traill iii Published by ANU E Press Design by Oblong + Sons Pty Ltd The Australian National University 07 3254 2586 Canberra ACT 0200, Australia www.oblong.net.au Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Printed by Printpoint using an environmentally Online version available at: http://epress. friendly waterless printing process, anu.edu.au/nature_na_citation.html eliminating greenhouse gas emissions and saving precious water supplies. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry This book has been printed on ecoStar 300gsm and 9Lives 80 Silk 115gsm The nature of Northern Australia: paper using soy-based inks. it’s natural values, ecological processes and future prospects. EcoStar is an environmentally responsible 100% recycled paper made from 100% ISBN 9781921313301 (pbk.) post-consumer waste that is FSC (Forest ISBN 9781921313318 (online) Stewardship Council) CoC (Chain of Custody) certified and bleached chlorine free (PCF). -

Adelaide Coastal Waters Information Sheet No. 3

Adelaide Coastal Waters Information Sheet No. 3 Changes in urban environments Issued August 2009 EPA 769/09: This information sheet is part of a series of Fact Sheets on the Adelaide coastal waters and the findings of the Adelaide Coastal Waters Study (ACWS). Introduction Since European settlement in the 1830s, the Adelaide plains and Adelaide’s coastal environment have been subject to considerable change and pressure from a continually increasing population. In recent years there has been growing community concern about the effects of coastal and catchment development on the marine environment. Increases in stormwater flows and waste from wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) have also been of concern. Nutrients and other pollutants introduced to Adelaide’s nearshore waters from urban and rural runoff, WWTPs and some industrial sources have been found by the Adelaide Coastal Waters Study (ACWS) to have had a negative impact on Adelaide’s nearshore marine environment, including the loss of over 5,000 hectares of seagrass. Historical catchment changes When Adelaide was selected by Colonel William Light for South Australia’s state capital in 1836 there was a wide belt of coastal dunes and wide sandy beaches stretching to the north and south of Glenelg. From Seacliff to Outer Harbor there was a 30 km stretch of sand dunes broken only by the Patawalonga Creek at Glenelg. The Torrens River flowed into a series of swamps lying behind the coastal dunes and drained both north and south to the sea through the Patawalonga Creek and Port River system. The stretch of sand dunes comprised two or more parallel ridges each about 70 to 100 metres wide separated by narrow depressions or swales, consequently very little surface catchment runoff would have reached the coastline. -

Inbound Flights Into Adelaide Sydney to Adelaide

INBOUND FLIGHTS INTO ADELAIDE SYDNEY TO ADELAIDE DATE AIRLINE FLIGHT NUMBER DEPARTURE CITY DEPARTURE TIME ARRIVAL CITY ARRIVAL TIME 11 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ762 SYDNEY 0700 ADELAIDE 0835 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF1555 SYDNEY 0815 ADELAIDE 0955 11 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA412 SYDNEY 0840 ADELAIDE 1020 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF741 SYDNEY 1045 ADELAIDE 1220 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF751 SYDNEY 1235 ADELAIDE 1410 11 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA418 SYDNEY 1240 ADELAIDE 1420 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF759 SYDNEY 1355 ADELAIDE 1530 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF761 SYDNEY 1510 ADELAIDE 1645 11 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ764 SYDNEY 1530 ADELAIDE 1705 11 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA428 SYDNEY 1610 ADELAIDE 1750 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF765 SYDNEY 1640 ADELAIDE 1815 11 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ768 SYDNEY 1725 ADELAIDE 1900 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF743 SYDNEY 1815 ADELAIDE 1950 11 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA436 SYDNEY 1815 ADELAIDE 1955 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF783 SYDNEY 1955 ADELAIDE 2130 11 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ770 SYDNEY 2015 ADELAIDE 2150 11 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA444 SYDNEY 2015 ADELAIDE 2155 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF785 SYDNEY 2035 ADELAIDE 2210 DATE AIRLINE FLIGHT NUMBER DEPARTURE CITY DEPARTURE TIME ARRIVAL CITY ARRIVAL TIME 12 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA403 SYDNEY 0645 ADELAIDE 0825 12 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ762 SYDNEY 0700 ADELAIDE 0835 12 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF735 SYDNEY 0705 ADELAIDE 0840 12 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF739 SYDNEY 0820 ADELAIDE 0955 12 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA412 SYDNEY 0840 ADELAIDE 1020 12 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ766 SYDNEY 1025 ADELAIDE 1200 12 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF741 SYDNEY 1045 ADELAIDE 1220 12 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF1557 SYDNEY 1130 ADELAIDE 1310 For any queries -

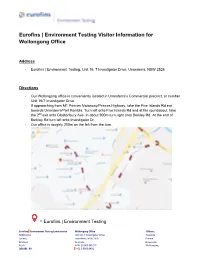

Environment Testing Visitor Information for Wollongong Office

Eurofins | Environment Testing Visitor Information for Wollongong Office Address - Eurofins | Environment Testing, Unit 16, 7 Investigator Drive, Unanderra, NSW 2526 Directions - Our Wollongong office is conveniently located in Unanderra’s Commercial precinct, at number Unit 16/7 Investigator Drive. - If approaching from M1 Princes Motorway/Princes Highway, take the Five Islands Rd exit towards Unanderra/Port Kembla. Turn left onto Five Islands Rd and at the roundabout, take the 2nd exit onto Glastonbury Ave. In about 900m turn right onto Berkley Rd. At the end of Berkley Rd turn left onto Investigator Dr. - Our office is roughly 200m on the left from the turn. = Eurofins | Environment Testing Eurofins Environment Testing Laboratories Wollongong Office Offices : Melbourne Unit 16, 7 Investigator Drive Adelaide Sydney Unanderra, NSW 2526 Darwin Brisbane Australia Newcastle Perth ABN: 50 005 085 521 Wollongong QS1081_R0 +61 2 9900 8492 Parking - There are 3 car spaces directly in front of the building, if the spaces are all occupied there is also on street parking out the front of the complex. General Information - The Wollongong office site includes a client services room available 24 hours / 7 days a week for clients to drop off samples and / or pick up bottles and stock. This facility available for Eurofins | Environment Testing clients, is accessed via a coded lock. For information on the code and how to utilize this access service, please contact Elvis Dsouza on 0447 584 487. - Standard office opening hours are between 8.30am to 5.00pm, Monday to Friday (excluding public holidays). We look forward to your visit. Eurofins | Environment Testing Management & Staff Eurofins Environment Testing Laboratories Wollongong Office Offices : Melbourne Unit 16, 7 Investigator Drive Adelaide Sydney Unanderra, NSW 2526 Darwin Brisbane Australia Newcastle Perth ABN: 50 005 085 521 Wollongong QS1081_R0 +61 2 9900 8492 . -

Nineteenth-Century Lunatic Asylums in South Australia and Tasmania (1830-1883)

AUSTRALASIAN HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, 19,2001 Convicts and the Free: Nineteenth-century lunatic asylums in South Australia and Tasmania (1830-1883) SUSAN PIDDOCK While most ofus are familiar with the idea ofthe lunatic asylum, few people realise that lunatic asylums were intended to be curative places where the insane were return to sanity. In the early nineteenth century a new treatment regime that emphasised the moral management of the insane person in the appropriate environment became popular. This environment was to be provided in the new lunatic asylums being built. This article looks at what this moral environment was and then considers it in the context ofthe provisions made for the insane in two colonies: South Australia and Tasmania. These colonies had totally different backgrounds, one as a colony offree settlers and the other as a convict colony. The continuing use ofnineteenth-century lunatic asylums as modern mental hospitals means that alternative approaches to the traditional approaches ofarchaeology have to be considered, and this article discusses documentary archaeology as one possibility. INTRODUCTION and Australia. In this paper a part of this study is highlighted, that being the provision of lunatic asylums in two colonies of While lunacy and the lunatic asylum are often the subject of Australia: South Australia and Tasmania. The first a colony academic research, little attention has been focused on the that prided itself on the lack of convicts within its society, and asylums themselves, as built environments in which the insane the second a colony which received convicts through the were to be bought back to sanity and returned to society. -

Cross-Cultural Conflicts in Fire Management in Northern Australia

Table of Contents Cross−cultural Conflicts in Fire Management in Northern Australia: Not so Black and White......................0 ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................................................0 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................1 INTEGRATING SCIENCE AND FIRE MANAGEMENT..........................................................................3 FIRE MANAGEMENT WITHOUT SCIENCE............................................................................................4 Strategic objectives...........................................................................................................................4 Performance indicators and feedback through research and monitoring..........................................5 ACQUISITION AND USE OF INFORMATION IN FIRE MANAGEMENT............................................5 CONCLUSION..............................................................................................................................................6 RESPONSES TO THIS ARTICLE...............................................................................................................8 Acknowledgments:.........................................................................................................................................8 LITERATURE CITED..................................................................................................................................9 -

SA Climate Ready Climate Projections for South Australia

South East SA Climate Ready Climate projections for South Australia This document provides a summary of rainfall The region and temperature (maximum and minimum) information for the South East (SE) Natural Resources The SE NRM region (from the Management (NRM) region generated using the northern Coorong and Tatiara districts latest group of international global climate models. to the coast in the south and west, Information in this document is based on a more and Victoria to the east) has wet, cool detailed regional projections report available winters and dry, mild-hot summers; at www.goyderinstitute.org. with increasing rainfall from north to south; coastal zones are dominated by Climate projections at a glance winter rainfall, whilst more summer rain is experienced in inland areas. The future climate of the SE NRM region will be drier and hotter, though the amount of global action on decreasing greenhouse The SA Climate Ready project gas emissions will influence the speed and severity of change. The Goyder Institute is a partnership between the South Decreases in rainfall are projected for all seasons, Australian Government through the Department of Environment, with the greatest decreases in spring. Water and Natural Resources, CSIRO, Flinders University, Average temperatures (maximum and minimum) are University of Adelaide, and the University of South Australia. projected to increase for all seasons. Slightly larger increases In 2011, the Goyder Institute commenced SA Climate Ready, in maximum temperature occur for the spring season. a project to develop climate projections for South Australia. The resulting information provides a common platform on which Government, business and the community can By the end of the 21st century develop solutions to climate change adaptation challenges. -

Returning to the Returning to the Northern Territory

Population Studies Group POPULATION STUDIES School for Social and Policy Research Charles Darwin University RESEARCH BRIEF Northern Territory 0909 ISSUE Number 2008004 [email protected] School for Social and Policy Research 2008 RETURNING TO THE NNNORTHERNNORTHERN TERRITORY KEY FINDINGS RESEARCH AIM • Although some out-migrants may be lost to To identify the the Northern Territory altogether, the characteristics of people who return to the telephone survey showed that 30% of Northern Territory respondents had left and returned to the after a period of absence Territory at least once. and the reasons fforororor • Return migration is often planned from the their return outset and can occur, for example, at the completion of fixed-term employment, medical treatment, study, travel or undertaking family commitments This Research Brief draws on data from the elsewhere. Territory Mobility • Return migration may be for a limited time Survey and in-depth with 23% of telephone survey respondents interviews conducted as saying they planned to leave again with two part of the Northern or three years. Territory Mobility Project. Funding for • Retaining a family home in the Territory the research was provides an emotional connection which may provided by an ARC encourage return migration. Linkage Grant. • Climate, suitable housing and existing social networks may encourage return migration of older ex-Territory residents. • For many years, the Northern Territory has This Research Brief been a destination to which people return. was prepared by What can be done to encourage people to Elizabeth CreedCreed. return and to extend the period of time they plan to spend in the Territory? POPULATION STUDIES GROUP RESEARCH BRIEF ISSUE 2008004: RETURNING TO THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Background Consistently high rates of population turnover in the Northern Territory result in annual gains and losses of significant numbers of residents. -

Soils of the Northern Territory Factsheet

Soils of the Northern Territory | factsheet Soils are developed over thousands of years and are made up of air, water, minerals, organic material and microorganisms. They can take on a wide variety of characteristics and form ecosystems which support all life on earth. In the NT, soils are an important natural resource for land-based agricultural industries. These industries and the soils that they depend on are a major contributor to the Northern Territory economy and need to be managed sustainably. Common Soils in the Northern Territory Kandosols Tenosols Hydrosols Often referred to as red, These weakly developed or sandy These seasonally inundated yellow and brown earths, soils are important for horticulture in soils support both high value these massive and earthy the Ali Curung and Alice Springs conservation areas important soils are important for regions. They soils show some for ecotourism as well as the agricultural and horticultural degree of development (minor pastoral industry. They production. They occur colour or soil texture increase in generally occur in higher throughout the NT and are subsoil) down the profile. They rainfall areas on coastal widespread across the Top include sandplains, granitic soils floodplains, swamps and End, Sturt plateau, Tennant and the sand dunes of beach ridges drainage lines. They also Creek and Central Australian and deserts. include soils in mangroves and regions. salt flats. Darwin sandy Katherine loamy Red Alice Springs Coastal floodplain Red Kandosol Kandosol sandplainTenosol Hydrosol Rudosols Chromosols These are very shallow soils or those with minimal These are soils with an abrupt increase in clay soil development. Rudosols include very shallow content below the top soil. -

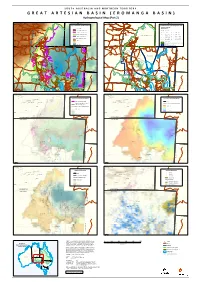

GREAT ARTESIAN BASIN Responsibility to Any Person Using the Information Or Advice Contained Herein

S O U T H A U S T R A L I A A N D N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y G R E A T A R T E S I A N B A S I N ( E RNturiyNaturiyaO M A N G A B A S I N ) Pmara JutPumntaara Jutunta YuenduYmuuendumuYuelamu " " Y"uelamu Hydrogeological Map (Part " 2) Nyirri"pi " " Papunya Papunya ! Mount Liebig " Mount Liebig " " " Haasts Bluff Haasts Bluff ! " Ground Elevation & Aquifer Conditions " Groundwater Salinity & Management Zones ! ! !! GAB Wells and Springs Amoonguna ! Amoonguna " GAB Spring " ! ! ! Salinity (μ S/cm) Hermannsburg Hermannsburg ! " " ! Areyonga GAB Spring Exclusion Zone Areyonga ! Well D Spring " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " " " " Extent of Saturated Aquifer ! D 1 - 500 ! D 5001 - 7000 Extent of Confined Aquifer ! D 501 - 1000 ! D 7001 - 10000 Titjikala Titjikala " " NT GAB Management Zone ! D ! Extent of Artesian Water 1001 - 1500 D 10001 - 25000 ! D ! Land Surface Elevation (m AHD) 1501 - 2000 D 25001 - 50000 Imanpa Imanpa ! " " ! ! D 2001 - 3000 ! ! 50001 - 100000 High : 1515 ! Mutitjulu Mutitjulu ! ! D " " ! 3001 - 5000 ! ! ! Finke Finke ! ! ! " !"!!! ! Northern Territory GAB Water Control District ! ! ! Low : -15 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! FNWAP Management Zone NORTHERN TERRITORY Birdsville NORTHERN TERRITORY ! ! ! Birdsville " ! ! ! " ! ! SOUTH AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!!!!! !!!! D !! D !!! DD ! DD ! !D ! ! DD !! D !! !D !! D !! D ! D ! D ! D ! D ! !! D ! D ! D ! D ! DDDD ! Western D !! ! ! ! ! Recharge Zone ! ! ! ! ! ! D D ! ! ! ! ! ! N N ! ! A A ! L L ! ! ! ! S S ! ! N N ! ! Western Zone E -

Australia's Northern Territory: the First Jurisdiction to Legislate Voluntary Euthanasia, and the First to Repeal It

DePaul Journal of Health Care Law Volume 1 Issue 3 Spring 1997: Symposium - Physician- Article 8 Assisted Suicide November 2015 Australia's Northern Territory: The First Jurisdiction to Legislate Voluntary Euthanasia, and the First to Repeal It Andrew L. Plattner Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jhcl Recommended Citation Andrew L. Plattner, Australia's Northern Territory: The First Jurisdiction to Legislate Voluntary Euthanasia, and the First to Repeal It, 1 DePaul J. Health Care L. 645 (1997) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jhcl/vol1/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Health Care Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AUSTRALIA'S NORTHERN TERRITORY: THE FIRST JURISDICTION TO LEGISLATE VOLUNTARY EUTHANASIA, AND THE FIRST TO REPEAL IT AndreivL. Plattner INTRODUCTION On May 25, 1995, the legislature for the Northern Territory of Australia enacted the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act,' [hereinafter referred to as the Act] which becane effective on July 1, 1996.2 However, in less than a year, on March 25, 1997, the Act was repealed by the Australian National Assembly.3 Australia's Northern Territory for a brief time was the only place in the world where specific legislation gave terminally ill patients the right to seek assistance from a physician in order to hasten a patient's death.4 This Article provides a historical account of Australia's Rights of the Terminally Ill Act, evaluates the factors leading to the Act's repeal, and explores the effect of the once-recognized right to assisted suicide in Australia.