Northern Territory Statehood Steering Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

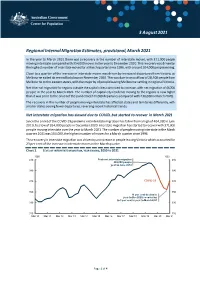

Regional Internal Migration Estimates, Provisional, March 2021

3 August 2021 Regional Internal Migration Estimates, provisional, March 2021 In the year to March 2021 there was a recovery in the number of interstate moves, with 371,000 people moving interstate compared with 354,000 moves in the year to December 2020. This recovery was driven by the highest number of interstate moves for a March quarter since 1996, with around 104,000 people moving. Close to a quarter of the increase in interstate moves was driven by increased departures from Victoria, as Melbourne exited its second lockdown in November 2020. This was due to an outflow of 28,500 people from Melbourne to the eastern states, with the majority of people leaving Melbourne settling in regional Victoria. Net internal migration for regions outside the capital cities continued to increase, with net migration of 44,700 people in the year to March 2021. The number of capital city residents moving to the regions is now higher than it was prior to the onset of the pandemic (244,000 departures compared with 230,000 in March 2020). The recovery in the number of people moving interstate has affected states and territories differently, with smaller states seeing fewer departures, reversing recent historical trends. Net interstate migration has slowed due to COVID, but started to recover in March 2021 Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic net interstate migration has fallen from a high of 404,000 in June 2019, to a low of 354,000 people in December 2020. Interstate migration has started to recover with 371,000 people moving interstate over the year to March 2021. -

In the Name of Failure: a Generational Revolution in Indigenous Affairs Will Sanders

In the Name of Failure: A Generational Revolution in Indigenous Affairs Will Sanders Introduction In April 2004, towards the end of its third term, the Howard Government announced its intention to abolish the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), the statutory centerpiece of Commonwealth Indigenous affairs administration over the previous fifteen years. In so doing Prime Minister Howard and his Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs, Senator Amanda Vanstone, referred to ATSIC as an ‘experiment in separate….elected representation, for Indigenous people’ which had been a ‘failure’ and which would not be replaced. Instead a group of ‘distinguished Indigenous people’ would be appointed to ‘advise’ the government and ATSIC’s former programs would be ‘mainstreamed’ to line government departments, though there would still be ‘a major policy role’ for the Minister for Indigenous Affairs (Howard and Vanstone 2004). In this essay, I will focus on the way in which the idea of past policy failure has become the driving motif of Australian Indigenous affairs during the fourth Howard Government and how, in the name of failure, the Government has argued repeatedly for significant organizational and policy change. The first section of the essay documents, in chronological style, this constant linking of the idea of failure with arguments for change. The second section asks, in a more analytic style, what sort of change is now occurring in Australian Indigenous affairs? I argue that the change is best thought of as a generational revolution, which combines a major disowning of the work of the previous generation in Indigenous affairs with a significant ideological swing to the right. -

1 to 8 Assembly

Legislative Assembly of the Northern Territory Northern Territory Government Ministries (CLP) 1st to 8 th Assembly 1974 - 2001 FIRST LETTS EXECUTIVE (November 1974 to August 1975) Dr G A Letts MLA Majority Leader and Executive Member for Primary Industry and the NT Public Service Mr P A E Everingham MLA Deputy Majority Leader and Executive Member for Finance and Law Mr G E J Tambling MLA Executive Member for Community Development Ms E J Andrew MLA Executive Member for Education and Consumer Services Mr D L Pollock MLA Executive Member for Social Affairs Mr I L Tuxworth MLA Executive Member for Resource Development Mr R Ryan MLA Executive Member for Transport and Secondary Industry SECOND LETTS EXECUTIVE (August 1975 to November 1975) Dr G A Letts MLA Majority Leader and Executive Member for Primary Industry and the NT Public Service Mr B F Kilgariff MLA Deputy Majority Leader and Executive Member for Finance and Law Mr G E J Tambling MLA Executive Member for Community Development Ms E J Andrew MLA Executive Member for Education and Consumer Services Mr D L Pollock MLA Executive Member for Social Affairs Mr I L Tuxworth MLA Executive Member for Resource Development Mr R Ryan MLA Executive Member for Transport and Secondary Industry THIRD LETTS EXECUTIVE (December 1975 to December 1976) Dr G A Letts MLA Majority Leader and Executive Member for Primary Industry and the NT Public Service Mr G E J Tambling MLA Deputy Majority Leader and Executive Member for Finance and Community Development Mr M B Perron MLA Executive Member for Municipal -

Northern Territory Government >Tm~

Submission No 29 Inquiry into Australia’s relationship with India as an emerging world power Organisation: Chief Minister — Minister for Asian Relation & Trade (Norhtern Territory Government) Contact Person: dare Martin Chief Minister Address: GPO BOX 3146 DARWIN NT 0801 Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Foreign Affafrs Sub-Committee CHIEF MINISTER MINISTER FOR ASIAN RELATIONS AND Pailioment House State Square Oarwb NT 08W T~ephone: 088901 4000 [email protected] Facsimile: 088901 4099 Senator AJan Ferguson Chair Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Senator Thank you for your letter of 3 April 2006, requesting the Northern Territory Minister for Primary industry, Fisheries and Mines to provide a submission to the inquiry into Australia’s relationship with India as an emerging world power. This request has been referred to me, as Minister for Asian Relations and Trade frw a response. India has enjoyed significant economic reform and growth over the past few years and various sectors have been opened up lbr trade and investment. The Northern Territory supports the strengthening of economic, political and sodal links for the mutual benefit of Australia and India. While merchandise trade with India is not strong, the Northern Territory is particularly interested in building and strengthening ties in the areas of skiiled migration, tertiary education, sport and the supply of gas to the Indian market. (Northern Territory — India trade sheetis attached). Australia’s total trade with India for 2005 amounted to $8 billion. With this volume of trade, there is an opportunity for the Northern Territory to position itself to take advantage of the two-way trade, through the Port of Darwin, as well as to develop shipping links with the major ports of India. -

Returning to the Returning to the Northern Territory

Population Studies Group POPULATION STUDIES School for Social and Policy Research Charles Darwin University RESEARCH BRIEF Northern Territory 0909 ISSUE Number 2008004 [email protected] School for Social and Policy Research 2008 RETURNING TO THE NNNORTHERNNORTHERN TERRITORY KEY FINDINGS RESEARCH AIM • Although some out-migrants may be lost to To identify the the Northern Territory altogether, the characteristics of people who return to the telephone survey showed that 30% of Northern Territory respondents had left and returned to the after a period of absence Territory at least once. and the reasons fforororor • Return migration is often planned from the their return outset and can occur, for example, at the completion of fixed-term employment, medical treatment, study, travel or undertaking family commitments This Research Brief draws on data from the elsewhere. Territory Mobility • Return migration may be for a limited time Survey and in-depth with 23% of telephone survey respondents interviews conducted as saying they planned to leave again with two part of the Northern or three years. Territory Mobility Project. Funding for • Retaining a family home in the Territory the research was provides an emotional connection which may provided by an ARC encourage return migration. Linkage Grant. • Climate, suitable housing and existing social networks may encourage return migration of older ex-Territory residents. • For many years, the Northern Territory has This Research Brief been a destination to which people return. was prepared by What can be done to encourage people to Elizabeth CreedCreed. return and to extend the period of time they plan to spend in the Territory? POPULATION STUDIES GROUP RESEARCH BRIEF ISSUE 2008004: RETURNING TO THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Background Consistently high rates of population turnover in the Northern Territory result in annual gains and losses of significant numbers of residents. -

Maurice Blackburn Oration an Issue of Equity: Is It Fair and Just That There

1 Maurice Blackburn Oration An Issue of Equity: Is it fair and just that there are 230,000 second-class citizens in the Northern Territory? Professor Clare Martin. It’s a great privilege to be invited to give the Maurice Blackburn Oration and to be the first from the Northern Territory to do so. My thanks to the Moreland City Council for the invitation and I pay my respects to the Wurundjeri people on whose land we meet tonight. Being the first Northern Territorian to deliver this prestigious oration, I thought it only appropriate to bring a Northern Territory perspective with me – a perspective that comes from living and working in the north for nearly 30 years and being a member of the Territory Parliament for 13 of those years, including six as Chief Minister. So my choice of subject tonight and one that I hope would be thoroughly approved of by both Maurice and Doris Blackburn is: An Issue of Equity: Is it fair and just that Northern Territorians, all 230,000 of us, are second-class citizens? And if, as I contend, we are second- class citizens, what does that actually mean? How have those lesser rights affected the course of Territory history; what affect has there been on our political institutions, our political effectiveness and engagement and importantly what effect on our community, especially Aboriginal Territorians who make up a third of our population? So some context about the Northern Territory to start For much of our history since European settlement the Territory has been unloved: a bit of an orphan. -

Arafura Resources Social Impact Assessment March 2016 37

3.2.3 Alice Springs The town of Alice Springs, initially called Stuart, grew up around the Telegraph Station on the Todd River and captured the Australian imagination as a ‘frontier’ land settled by cattle pioneers following the trails of early explorers. Current transport routes, geographical features and place names reflect the travels and aspirations of these early settlers and their colonial masters. In 1860, the Scottish-born explorer John McDouall Stuart travelled through, naming the MacDonnell Ranges after the Governor of South Australia and writing in glowing terms of the Central Australian landscape, which he 37 believed held out excellent prospects for pastoral development (Carment 1991). In 1863, what is now the Northern Territory was transferred from New South Wales to South Australia. In October 1870, the South Australian Government decided to build a telegraph line from Port Augusta to Port Darwin to link with a sub-sea cable to Britain, the first of many nation-building projects associated with the Northern Territory. The work began under the supervision of Charles Todd, with new telegraph stations at Charlotte Waters, Alice Springs, Barrow Creek and Powell Creek. Planning a route for the telegraph line brought in explorers such as WC Gosse who named Ayers Rock in 1873 after South Australian Premier, Sir Henry Ayres, while Alice Springs was the name given to the springs at the telegraph station after Todd’s wife, Alice. The present town of Alice Springs was named after Stuart and proclaimed in 1888. It was close to the Alice Springs Telegraph Station and just north of Heavitree Gap. -

Māori and Aboriginal Women in the Public Eye

MĀORI AND ABORIGINAL WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC EYE REPRESENTING DIFFERENCE, 1950–2000 MĀORI AND ABORIGINAL WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC EYE REPRESENTING DIFFERENCE, 1950–2000 KAREN FOX THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Fox, Karen. Title: Māori and Aboriginal women in the public eye : representing difference, 1950-2000 / Karen Fox. ISBN: 9781921862618 (pbk.) 9781921862625 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Women, Māori--New Zealand--History. Women, Aboriginal Australian--Australia--History. Women, Māori--New Zealand--Social conditions. Women, Aboriginal Australian--Australia--Social conditions. Indigenous women--New Zealand--Public opinion. Indigenous women--Australia--Public opinion. Women in popular culture--New Zealand. Women in popular culture--Australia. Indigenous peoples in popular culture--New Zealand. Indigenous peoples in popular culture--Australia. Dewey Number: 305.4880099442 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover image: ‘Maori guide Rangi at Whakarewarewa, New Zealand, 1935’, PIC/8725/635 LOC Album 1056/D. National Library of Australia, Canberra. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Abbreviations . ix Illustrations . xi Glossary of Māori Words . xiii Note on Usage . xv Introduction . 1 Chapter One . -

Legislative Assembly Results Summary of Legislative Assembly Election

2001 NORTHERN TERRITORY ELECTION 18 August 2001 CONTENTS Page Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 Legislative Assembly Results Summary of Legislative Assembly Election ..................................................... 3 Legislative Assembly Results by Electoral Division ......................................... 6 Summary of Two-Party Preferred Results ..................................................... 11 Regional Summaries ..................................................................................... 12 By-elections 1997-2001 ............................................................................................ 14 Antony Green ABC Election Unit Symbols .. Nil or rounded to zero * Sitting MPs .… „Ghost‟ candidate, where a party contesting the previous election did not nominate for the current election Party Abbreviations (blank) Non-affiliated candidates CLP Country Liberal Party DEM Australian Democrats GRN Green IND Independent LAB Territory Labor ONP One Nation SAP Socialist Alliance Party TAP Territory Alliance Party 2001 Northern Territory Election INTRODUCTION This paper contains a summary of the 2001 Northern Territory election. For each Legislative Assembly electorate, details of the total primary and two-candidate preferred vote are provided. Where appropriate, a two-party preferred count is also included. The format for the results is as follows: First Count: For each candidate, the total primary vote received is shown. -

The Great Debate: ‘Income Tax Should Be Increased to Assist with Australia’S Economic Recovery’

The Great Debate: ‘Income Tax Should be Increased to Assist with Australia’s Economic Recovery’ Communities in Control Conference Melbourne, 16 June, 2009 Adjudicated by The Honourable Joan Kirner AM Victorian Community Ambassador, former Premier of Victoria And featuring Clare Martin CEO of ACOSS (Australian Council of Social Service) Brett de Hoedt showman, media trainer and Mayor, Hootville Communications Joan Hughes CEO, Carers Australia Lesley Hall CEO, Australian Federation of Disability Organisations Please Note: This was a light‐hearted debate. The views expressed in this transcript do not necessarily reflect those held by the speakers Page 2 Joan Kirner: Thank you very much, Joe. Thank you everyone for your welcome but it wasn’t really loud enough. [Applause] That’s better. You can say that when you’re no longer in power. You can’t say it when you’re in power. This is my one opportunity to exercise power for the year,l rea power. I’ve got the time and I’ve got some control, although having Clare over there worries me a bit. And we’re going to have our usual great debate. But I’ll first acknowledge that I’m standing on the land of the Kulin Nation and thank them for their custodianship of this land and pledge to work with them, their current Elders and their communities, to get the kind of community in control that Mick was talking about. And, you know, I can never resist interfering with a motion, so if you’re going to send a letter to Jenny Macklin, I think that’s a terrific idea but it’s an even better to ask for a deputation of many of the organisations represented here. -

Essay: Trapped in the Aboriginal Reality Show

Essay: Trapped in the Aboriginal reality show Author: Marcia Langton ean Baudrillard generated international controversy when he described in his essay ‘War Porn’ the way images from Abu Graib prison in Iraq and other J‘consensual and televisual’ violence were used in the aftermath to September 11, 2001. Strong words – perversity, vileness – sparked in his brief, acute analysis: ‘The worst is that it all becomes a parody of violence, a parody of the war itself, pornography becoming the ultimate form of the abjection of war which is unable to be simply war, to be simply about killing, and instead turns itself into a grotesque infantile reality‐show, in a desperate simulacrum of power. These scenes are the illustration of a power, without aim, without purpose, without a plausible enemy, and in total impunity. It is only capable of inflicting gratuitous humiliation.’ This made me think about the everyday suffering of Aboriginal children and women, the men who assault and abuse them, and the use of this suffering as a kind of visual and intellectual pornography in Australian media and public debates. The very public debate about child abuse is like Baudrillard’s ‘war porn’. It has parodied the horrible suffering of Aboriginal people. The crisis in Aboriginal society is now a public spectacle, played out in a vast ‘reality show’ through the media, parliaments, public service and the Aboriginal world. This obscene and pornographic spectacle shifts attention away from everyday lived crisis that many Aboriginal people endure – or do not, dying as they do at excessive rates. This spectacle is not a new phenomenon in Australian public life, but the debate about ‘Indigenous affairs’ has reached a new crescendo, fuelled by the accelerated and uncensored exposé of the extent of Aboriginal child abuse. -

Report on Statehood Program

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Report on Statehood Program Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee Tabled February 2012 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee Report on the Statehood Program Tabled in the Legislative Assembly in February 2012 CONTENTS Contents ................................................................................................... i Chair’s Overview ............................................................................................ ii Committee Members ..................................................................................... iv Committee Secretariat ................................................................................... v 1. Introduction.............................................................................................. 1 2. Background.............................................................................................. 2 Recommendations of the SSC ................................................................................................. 2 Northern Territory Constitutional Convention Committee......................................................... 4 Information Campaign .............................................................................................................. 4 Current Status of the Statehood Program ................................................................................ 4 3. Convention Planning..............................................................................