19. Liberty Square

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

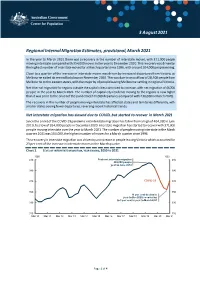

Regional Internal Migration Estimates, Provisional, March 2021

3 August 2021 Regional Internal Migration Estimates, provisional, March 2021 In the year to March 2021 there was a recovery in the number of interstate moves, with 371,000 people moving interstate compared with 354,000 moves in the year to December 2020. This recovery was driven by the highest number of interstate moves for a March quarter since 1996, with around 104,000 people moving. Close to a quarter of the increase in interstate moves was driven by increased departures from Victoria, as Melbourne exited its second lockdown in November 2020. This was due to an outflow of 28,500 people from Melbourne to the eastern states, with the majority of people leaving Melbourne settling in regional Victoria. Net internal migration for regions outside the capital cities continued to increase, with net migration of 44,700 people in the year to March 2021. The number of capital city residents moving to the regions is now higher than it was prior to the onset of the pandemic (244,000 departures compared with 230,000 in March 2020). The recovery in the number of people moving interstate has affected states and territories differently, with smaller states seeing fewer departures, reversing recent historical trends. Net interstate migration has slowed due to COVID, but started to recover in March 2021 Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic net interstate migration has fallen from a high of 404,000 in June 2019, to a low of 354,000 people in December 2020. Interstate migration has started to recover with 371,000 people moving interstate over the year to March 2021. -

Suncorp Bank Family Friendly City Report Introduction

Suncorp Bank Family Friendly City Report Introduction Launceston and Canberra have scooped the pool as Australia’s most family friendly cities, bumping Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane to 14th, 23rd and 24th positions respectively, according to a study into the family friendliness of the nation’s 30 largest cities. The inaugural Suncorp Bank Family Friendly Index shows that half of the top 10 family friendly cities are not state or territory capitals and instead include the smaller, regional cities of Albury/Wodonga, Toowoomba, and Launceston. The report finds that crowded, stressful, urban jungles and under serviced Eastern seaboard capitals are being upstaged by regional towns as the most family friendly cities in Australia. The inaugural Suncorp Bank Family Friendly City Index monitors the most populated 30 cities in Australia and ranks them according to which city is the most family friendly across 10 key indicators. The indicators themselves are divided into two categories; Primary and Secondary. Primary indicators refer to those indicators that have a larger bearing on a city’s ‘livability’, (such as, crime education and housing) as such these indicators are weighted double that of the secondary indicators. While the Index analyses indicators such as Education, Crime, Health, Income, Unemployment and Connectivity, some notable omissions include Environment (climate and weather), Lifestyle (beaches and parks) which have not been included due to their subjective nature and a lack of consistent data for each of the 30 cities analysed. Methodology To derive the rankings for the Suncorp Bank Family Friendly City Index each city was systematically ranked on each of the 10 indicators. -

International Course Guide 2022

International Course Guide 2022 01 Federation University Australia acknowledges Wimmera Wotjobaluk, Jaadwa, Jadawadjali, Wergaia, Jupagulk the Traditional Custodians of the lands and waters where our campuses, centres and field Ballarat Wadawurrung stations are located and we pay our respects to Elders past and present. We extend this Berwick Boon Wurrung and Wurundjeri respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and First Nations Peoples. Gippsland Gunai Kurnai The Aboriginal Traditional Custodians of the Nanya Station Mutthi Mutthi and Barkindji lands and waters where our campuses, centres and field stations are located include: Brisbane Turrbal and Jagera At Federation University, we’re driven to make a real difference. To the lives of every student who Federation University 01 Education and Early Childhood 36 walks through our doors, and to the communities Reasons to choose Federation University 03 Engineering 42 Find out where you belong 05 Health 48 we help build and are proud to be part of. Regional and city living 06 Humanities, Social Sciences, Criminology We are one of Australia’s oldest universities, known today and Social Work 52 Our campuses and locations 08 for our modern approach to teaching and learning. For 150 years Information Technology 56 we have been reaching out to new communities, steadily building Industry connections 12 Performing Arts, Visual Arts and Design 60 a generation of independent thinkers united in the knowledge Student accommodation 14 that they are greater together. Psychology 62 Our support services and programs 16 Science 64 Be part of our diverse community International Student Support 18 Sport, Health, Physical and Outdoor Education 66 Today, we are proud to have more than 21,000 Australian Experience uni life 19 and international students and 114,000 alumni across Australia Higher Degrees by Research 68 Study abroad and exchange 20 and the world. -

Returning to the Returning to the Northern Territory

Population Studies Group POPULATION STUDIES School for Social and Policy Research Charles Darwin University RESEARCH BRIEF Northern Territory 0909 ISSUE Number 2008004 [email protected] School for Social and Policy Research 2008 RETURNING TO THE NNNORTHERNNORTHERN TERRITORY KEY FINDINGS RESEARCH AIM • Although some out-migrants may be lost to To identify the the Northern Territory altogether, the characteristics of people who return to the telephone survey showed that 30% of Northern Territory respondents had left and returned to the after a period of absence Territory at least once. and the reasons fforororor • Return migration is often planned from the their return outset and can occur, for example, at the completion of fixed-term employment, medical treatment, study, travel or undertaking family commitments This Research Brief draws on data from the elsewhere. Territory Mobility • Return migration may be for a limited time Survey and in-depth with 23% of telephone survey respondents interviews conducted as saying they planned to leave again with two part of the Northern or three years. Territory Mobility Project. Funding for • Retaining a family home in the Territory the research was provides an emotional connection which may provided by an ARC encourage return migration. Linkage Grant. • Climate, suitable housing and existing social networks may encourage return migration of older ex-Territory residents. • For many years, the Northern Territory has This Research Brief been a destination to which people return. was prepared by What can be done to encourage people to Elizabeth CreedCreed. return and to extend the period of time they plan to spend in the Territory? POPULATION STUDIES GROUP RESEARCH BRIEF ISSUE 2008004: RETURNING TO THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Background Consistently high rates of population turnover in the Northern Territory result in annual gains and losses of significant numbers of residents. -

Soils of the Northern Territory Factsheet

Soils of the Northern Territory | factsheet Soils are developed over thousands of years and are made up of air, water, minerals, organic material and microorganisms. They can take on a wide variety of characteristics and form ecosystems which support all life on earth. In the NT, soils are an important natural resource for land-based agricultural industries. These industries and the soils that they depend on are a major contributor to the Northern Territory economy and need to be managed sustainably. Common Soils in the Northern Territory Kandosols Tenosols Hydrosols Often referred to as red, These weakly developed or sandy These seasonally inundated yellow and brown earths, soils are important for horticulture in soils support both high value these massive and earthy the Ali Curung and Alice Springs conservation areas important soils are important for regions. They soils show some for ecotourism as well as the agricultural and horticultural degree of development (minor pastoral industry. They production. They occur colour or soil texture increase in generally occur in higher throughout the NT and are subsoil) down the profile. They rainfall areas on coastal widespread across the Top include sandplains, granitic soils floodplains, swamps and End, Sturt plateau, Tennant and the sand dunes of beach ridges drainage lines. They also Creek and Central Australian and deserts. include soils in mangroves and regions. salt flats. Darwin sandy Katherine loamy Red Alice Springs Coastal floodplain Red Kandosol Kandosol sandplainTenosol Hydrosol Rudosols Chromosols These are very shallow soils or those with minimal These are soils with an abrupt increase in clay soil development. Rudosols include very shallow content below the top soil. -

Our Cultural Collections a Guide to the Treasures Held by South Australia’S Collecting Institutions Art Gallery of South Australia

Our Cultural Collections A guide to the treasures held by South Australia’s collecting institutions Art Gallery of South Australia. South Australian Museum. State Library of South Australia. Car- rick Hill. History SA. Art Gallery of South Aus- tralia. South Australian Museum. State Library of South Australia. Carrick Hill. History SA. Art Gallery of South Australia. South Australian Museum. State Library of South Australia. Car- rick Hill. History SA. Art Gallery of South Aus- Published by Contents Arts South Australia Street Address: Our Cultural Collections: 30 Wakefield Street, A guide to the treasures held by Adelaide South Australia’s collecting institutions 3 Postal address: GPO Box 2308, South Australia’s Cultural Institutions 5 Adelaide SA 5001, AUSTRALIA Art Gallery of South Australia 6 Tel: +61 8 8463 5444 Fax: +61 8 8463 5420 South Australian Museum 11 [email protected] www.arts.sa.gov.au State Library of South Australia 17 Carrick Hill 23 History SA 27 Artlab Australia 43 Our Cultural Collections A guide to the treasures held by South Australia’s collecting institutions The South Australian Government, through Arts South Our Cultural Collections aims to Australia, oversees internationally significant cultural heritage ignite curiosity and awe about these collections comprising millions of items. The scope of these collections is substantial – spanning geological collections, which have been maintained, samples, locally significant artefacts, internationally interpreted and documented for the important art objects and much more. interest, enjoyment and education of These highly valuable collections are owned by the people all South Australians. of South Australia and held in trust for them by the State’s public institutions. -

Australia's Northern Territory: the First Jurisdiction to Legislate Voluntary Euthanasia, and the First to Repeal It

DePaul Journal of Health Care Law Volume 1 Issue 3 Spring 1997: Symposium - Physician- Article 8 Assisted Suicide November 2015 Australia's Northern Territory: The First Jurisdiction to Legislate Voluntary Euthanasia, and the First to Repeal It Andrew L. Plattner Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jhcl Recommended Citation Andrew L. Plattner, Australia's Northern Territory: The First Jurisdiction to Legislate Voluntary Euthanasia, and the First to Repeal It, 1 DePaul J. Health Care L. 645 (1997) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jhcl/vol1/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Health Care Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AUSTRALIA'S NORTHERN TERRITORY: THE FIRST JURISDICTION TO LEGISLATE VOLUNTARY EUTHANASIA, AND THE FIRST TO REPEAL IT AndreivL. Plattner INTRODUCTION On May 25, 1995, the legislature for the Northern Territory of Australia enacted the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act,' [hereinafter referred to as the Act] which becane effective on July 1, 1996.2 However, in less than a year, on March 25, 1997, the Act was repealed by the Australian National Assembly.3 Australia's Northern Territory for a brief time was the only place in the world where specific legislation gave terminally ill patients the right to seek assistance from a physician in order to hasten a patient's death.4 This Article provides a historical account of Australia's Rights of the Terminally Ill Act, evaluates the factors leading to the Act's repeal, and explores the effect of the once-recognized right to assisted suicide in Australia. -

Influences of German Science and Scientists on Melbourne Observatory

CSIRO Publishing The Royal Society of Victoria, 127, 43–58, 2015 www.publish.csiro.au/journals/rs 10.1071/RS15004 INFLUENCES OF GERMAN SCIENCE AND SCIENTISTS ON MELBOURNE OBSERVATORY Barry a.J. Clark Astronomical Society of Victoria Inc. PO Box 1059, GPO Melbourne 3001 Correspondence: Barry Clark, [email protected] ABSTRACT: The multidisciplinary approach of Alexander von Humboldt in scientific studies of the natural world in the first half of the nineteenth century gained early and lasting acclaim. Later, given the broad scientific interests of colonial Victoria’s first Government Astronomer Robert Ellery, one could expect to find some evidence of the Humboldtian approach in the operations of Williamstown Observatory and its successor, Melbourne Observatory. On examination, and without discounting the importance of other international scientific contributions, it appears that Melbourne Observatory was indeed substantially influenced from afar by Humboldt and other German scientists, and in person by Georg Neumayer in particular. Some of the ways in which these influences acted are obvious but others are less so. Like the other Australian state observatories, in its later years Melbourne Observatory had to concentrate its diminishing resources on positional astronomy and timekeeping. Along with Sydney Observatory, it has survived almost intact to become a heritage treasure, perpetuating appreciation of its formative influences. Keywords: Melbourne Observatory, 19th century, Neumayer, German science The pioneering holistic approach of Alexander von (Geoscience Australia 2015). In 1838 Carl Friedrich Gauss Humboldt in his scientific expeditions to study the natural helped put Humboldt’s call into practice by setting up world had a substantial, lasting and international influence the Göttinger Magnetische Verein (Göttingen Magnetic on a broad range of scientific fields. -

Settlement Engagement and Transition Support (SETS)

Settlement Engagement and Transition Support (SETS) - Successful Applicants Note: The final list of providers is subject to Funding Agreement negotiations with successful applicants. State/Territory of LEGAL ENTITY NAME Service Area/s Service Area/s Client Services Access Community Services Ltd QLD Gold Coast, Ipswich, Logan - Beaudesert African Women's Federation of SA Inc SA Adelaide - North, Adelaide - South, Adelaide - West Albury-Wodonga Volunteer Resource Bureau Inc NSW & VIC Albury (NSW), Wodonga (VIC) Anglicare N.T. Ltd NT Darwin Anglicare SA Ltd SA Adelaide - North Arabic Welfare Inc VIC Brunswick - Coburg, Moreland - North, Tullamarine - Broadmeadows, Whittlesea - Wallan Asian Women at Work Inc NSW Auburn, Bankstown, Blacktown, Canterbury, Fairfield, Hurstville Assyrian Australian Association NSW Blacktown, Ryde, Sydney South West Australian Afghan Hassanian Youth Association Inc NSW NSW Australian Muslim Women's Centre for Human Rights Inc VIC Melbourne - Inner, Melbourne - North East, Melbourne - North West, Melbourne - South East, Melbourne - West Australian Refugee Association Inc SA Adelaide - Central and Hills, Adelaide - North, Adelaide - South, Adelaide - West Ballarat Community Health VIC Ararat Region, Ararat, Ballarat Bendigo Community Health Services Ltd VIC Bendigo Brisbane South Division Ltd QLD Brisbane - East, Brisbane - North, Brisbane - South, Brisbane - West, Brisbane - Inner City Bundaberg & District Neighbourhood Centre Inc QLD Bundaberg CatholicCare Victoria Tasmania VIC & TAS TAS: Hobart VIC: Melbourne -

BENDIGO EC U 0 10 Km

Lake Yando Pyramid Hill Murphy Swamp July 2018 N Lake Lyndger Moama Boort MAP OF THE FEDERAL Little Lake Boort Lake BoortELECTORAL DIVISION OF Echuca Woolshed Swamp MITIAMO RD H CA BENDIGO EC U 0 10 km Strathallan Y RD W Prairie H L O Milloo CAMPASPE D D I D M O A RD N Timmering R Korong Vale Y P Rochester Lo d d o n V Wedderburn A Tandarra N L R Greens Lake L E E M H IDLAND Y ek T HWY Cre R O Corop BENDIGO Kamarooka East N R Elmore Lake Cooper i LODDON v s N H r e W e O r Y y r Glenalbyn S M e Y v i Kurting N R N E T Bridgewater on Y Inglewood O W H Loddon G N I Goornong O D e R N D N p C E T A LA s L B ID a H D M p MALLEE E E R m R Derby a Huntly N NICHOLLS Bagshot C H Arnold Leichardt W H Y GREATER BENDIGO W Y WIMM Marong Llanelly ERA HWY Moliagul Newbridge Bendigo M Murphys CIVOR Tarnagulla H Creek WY Redcastle STRATHBOGIE Strathfieldsaye Knowsley Laanecoorie Reservoir Lockwood Shelbourne South Derrinal Dunolly Eddington Bromley Ravenswood BENDIGO Lake Eppalock Heathcote Tullaroop Creek Ravenswood South Argyle C Heathcote South A L D locality boundary E Harcourt R CENTRAL GOLDFIELDS Maldon Cairn Curran Dairy Flat Road Reservoir MOUNT ALEXANDER Redesdale Maryborough PYRENEES Tooborac Castlemaine MITCHELL Carisbrook HW F Y W Y Moolort Joyces Creek Campbells Chewton Elphinstone J Creek Pyalong o Newstead y c Strathlea e s Taradale Talbot Benloch locality MACEDON Malmsbury boundary Caralulup C RANGES re k ek e re Redesdale Junction C o Kyneton Pastoria locality boundary o r a BALLARAT g Lancefield n a Clunes HEPBURN K Woodend Pipers Creek -

Front Cover Page

The Rotary Club of Darwin Sunrise TThhee FFiirrsstt 1166 YYeeaarrss 1989-2005 The logo was designed by Past District Governor and Charter member of the Rotary Club of Darwin Sunrise Guan Teik Yeo and depicts an image of a rising sun, in the form of the Rotary Wheel radiating the energy of Rotary, and an Aboriginal art stylised barramundi. The barramundi is a well known icon of the Top End and is shown as "Walking on Water". The barramundi has not been incorporated in any other Rotary banner in Australia, and the Aboriginal-like design recognises the Indigenous heritage in the Northern Territory. First Edition: 2005 Published by the Rotary Club of Darwin Sunrise Incorporated GPO Box 994, DARWIN, NT 0801 www.rotarnet.com.au/darwinsunrise Launched by His Honour, Mr Ted Egan AO, Administrator of the Northern Territory on 26th July 2005 at Government House. Acknowledgments and thanks to the Club History Working Party Chairperson IPP Malika Okeil Committee Members PP Reg Prasad PHF, PP Martyn Wilkinson PHF, PP Frank Stewart PHF, and other contributing present and past members FFOORREEWWOORRDD By Historian Alan Powell - Emeritus Professor of History, Charles Darwin University and Charter Member of the Rotary Club of Darwin Sunrise. In Rotary's Centennial year 2005 it is timely to remember the achievements of both Rotary International and the Rotary Club of Darwin Sunrise. Rotary was founded in the last years of true liberalism, when British historian, Lord Acton, could say that history equated with progress and all understanding was within reach of humankind. Rotary's ideals reflect that view; fairness, truth, peace, service. -

Aboriginal-Darwin-Contents.Pdf

Aboriginal Darwin contents Contents Welcome to Larrakia Country Responsible Travel Acknowledgements Authors About this Book Aboriginal Darwin Today Looking Back Tour Suggestions and Getting Around Precincts and Sites Aboriginal Events and Organisations Selected References Travelling Respectfully Index Precincts and Sites Precinct 1 Darwin Harbour Site 1 Darwin Harbour Site 2 Charles Darwin National Park Precinct 2 The Wharf Site 3 Stokes Hill Wharf Site 4 Australian Pearling Exhibition Site 5 WWII Oil Storage Tunnels Read about Fort Hill Wharf Read about Police Paddock Precinct 3 Along the Esplanade Site 6 Government House Site 7 Damoe-Ra Park Site 8 Lyons Cottage Site 9 Old Darwin Oval Site 10 Lameroo Beach and Doctors Gully Site 11 North Australia Observer Unit Commemorative Plaque Site 12 200 Remarkable Territorians Commemorative Tiles Precinct 4 CBD Site 13 NT Legislative Assembly, State Square Site 14 NT Supreme Court, State Square Site 15 City Centre Precinct 5 Myilly Point and the Gardens Site 16 Gardens Oval Site 17 George Brown Darwin Botanic Gardens Site 18 Mindil Beach Read about Emery Point Read about Kahlin Aboriginal Compound and the Half-Caste Home Precinct 6 Fannie Bay Site 19 Bullocky Point and Vesteys Beach Site 20 Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT) Site 21 Fannie Bay Gaol Read about Parap Camp Precinct 7 East Point Reserve Site 22 Monsoon Forest Walk and Mangrove Board Walk Site 23 East Point Military Museum and surrounds Precinct 8 Northern Suburbs Site 24 Karu Park Site 25 Nightcliff Nungalinya Fish Trap Site 26 Casuarina Coastal Reserve Site 27 Rapid Creek (Gurumbai) Read about Bagot Aboriginal Community Inc.