Cultural Responsiveness Framework

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of FNCFS Agencies in Saskatchewan

There are currently 19 Delegated Child and Family Services Agencies in Saskatchewan providing Child Protection and Prevention Services for First Nations Communities. Delegated Child & Family Service Agencies in Saskatchewan 1 Agency Chiefs Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-883-3345 Pelican Lake First Nation P.O. Box 329 TFree: 1-888-225-2244 Witchekan Lake First Nation Spiritwood, SK S0J 2M0 Fax: 306-883-3838 Whitecap Dakota First Nation Executive Director: Rick Dumais Email: [email protected] 2 Ahtahkakoop Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-468-2520 Ahtahkakoop First Nation P.O. Box 10 TFree: 1-888-745-0478 Mont Nebo, SK S0J 1X0 Fax: 306-468-2524 Executive Director: Anita Ahenakew Email: [email protected] 3 Athabasca Denesuline Child & Family Services Phone: 306-284-4915 Black Lake Denesuline Nation Inc. TFree: 1-888-439-4995 Fond du Lac Denesuline Nation (Yuthe Dene Sekwi Chu L A Koe Betsedi Inc.) Fax: 306-284-4933 Hatchet Lake Denesuline Nation P.O. Box 189 Black Lake, SK S0J 0H0 Acting Executive Director: Rosanna Good Email: Rgood@[email protected] 4 Awasisak Nikan Child & Family Services Phone: 306-845-1426 Thunderchild First Nation Thunderchild Child and Family Services Inc. Executive Director: Bertha Paddy Email: [email protected] 5 Kanaweyimik Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-445-3500 Moosomin First Nation P.O. Box 1270 TFree: 1-888-445-5262 Mosquito Grizzly Bear’s Head Battleford, SK S0M 0E0 Fax: 306-445-2533 First Nation Red Pheasant First Nation Executive Director: Marlene Bugler Saulteaux First Nation Email: [email protected] Sweetgrass First Nation 6 Keyanow Child & Family Centre Inc. -

Preliminary Demographic Analysis of First Nations and Métis People

○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ APPENDIX F Preliminary Demographic Analysis of First Nations and Métis People A Background Paper Prepared for the Regina QuAppelle Health Region Working Together Towards Excellence Project September 2002 1. Introduction ........................................................................ 2 By Project Staff Team: Rick Kotowich 2. Findings Joyce Racette ........................................................................ 3 Dale Young The Size of the First Nations and Métis Alex Keewatin Populations ..................................................... 3 John Hylton The Characteristics of These Populations....... 6 The Trends ...................................................... 8 3. Conclusion ........................................................................ 9 Appendix F 1 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 1. Introduction 2. It has been well documented that even in the CMAs where census data is available, it often significantly underestimates the true size of the Aboriginal Regina Qu’Appelle Health Region population. This occurs for many reasons, including the fact that Aboriginal people tend to fill out fewer The purpose of this brief paper is to provide a census forms. Moreover, conventional methods for preliminary analysis of available population and estimating the gap in reporting do not always take demographic data for the First Nations and Métis account of the larger size of Aboriginal people who live within the geographic -

Imprisonment, Carceral Space, and Settler Colonial Governance in Canada

COLONIAL CARCERALITY AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: IMPRISONMENT, CARCERAL SPACE, AND SETTLER COLONIAL GOVERNANCE IN CANADA By JESSICA E. JURGUTIS B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Jessica E. Jurgutis, September 2018 i DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (2018) McMaster University (Political Science) Hamilton, ON TITLE: Colonial Carcerality and International Relations: Imprisonment, Carceral Space, and Settler Colonial Governance in Canada AUTHOR: Jessica E. Jurgutis, B.A. (McMaster University), M.A. (York University) SUPERVISOR: Professor J. Marshall Beier NUMBER OF PAGES: vii, 335 ii Abstract This dissertation explores the importance of colonial carcerality to International Relations and Canadian politics. I argue that within Canada, practices of imprisonment and the production of carceral space are a foundational method of settler colonial governance because of the ways they are utilized to reorganize and reconstitute the relationships between bodies and land through coercion, non-consensual inclusion and the use of force. In this project I examine the Treaties and early agreements between Indigenous and European nations, pre-Confederation law and policy, legislative and institutional arrangements and practices during early stages of state formation and capitalist expansion, and contemporary claims of “reconciliation,” alongside the ongoing resistance by Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island. I argue that Canada employs carcerality as a strategy of assimilation, dispossession and genocide through practices of criminalization, punishment and containment of bodies and lands. Through this analysis I demonstrate the foundational role of carcerality to historical and contemporary expressions of Canadian governance within empire, by arguing land as indispensable to understanding the utility of imprisonment and carceral space to extending the settler colonial project. -

Environmental Overview

Vantage Pipeline Project Environmental and Socio-Economic Assessment Section 18: Traditional Knowledge Study Table 18-1 Legislation, Guidelines and Policies Related to First Nation and Métis Consultation REGULATORY GUIDELINES, PERMITS, GOVERNMENT AGENCIES LEGISLATION POLICIES Government of Alberta Various Various Guidelines are set out in Alberta’s First Nations Consultation Guidelines on Land Management and Resource Development (2007) Government of Various Various Guidelines are set out First Saskatchewan Nation and Métis Consultation Policy Framework June 2010 (2010) Federal Various The NEB Act Guidelines set out in (Government of Aboriginal Consultation Canada 1985) and Accommodation: CEAA Interim Guidelines for (Government of Federal Officials to Fulfill Canada 1992) the Legal Duty to Consult (2008) Aboriginal engagement and a TKS is a required by the NEB under the CEAA 18.2 Cultural and Historical Setting Individual Aboriginal consultation and TKS are part of a larger political, historical, and cultural framework which is unique for each First Nation and Métis community (Frideres and Krosenbrink-Gelissen 1998, Dickason 2010). Consultation often takes place between communities with very different worldviews and political histories. Recognizing this context is key to successful consultation which can benefit Aboriginal groups and other stakeholders. 18.3 Participating Aboriginal Groups Identifying Aboriginal groups which may be impacted by the Project is difficult. Proximity of the proposed right-of-way (ROW) to reserves or communities cannot be the only measure as it may not engage all interested communities given the modern political landscape does not fully reflect traditional land use. Prior to the signing of treaties and the reserve system, Aboriginal groups had much larger areas of traditional land use (Binnema 2001, Peck 2010). -

Line 3 Replacement Program Engagement Log

Enbridge Pipelines Inc. Quarter 3 Line 3 Replacement Program Aboriginal Engagement Log (June 15 - September 15, 2015) Line 3 Replacement Program Engagement Log Records Found: 100 Agency Chiefs Tribal Council Aboriginal - First Nations Community Contact Date: Jul 08, 2015 15:30 Enbridge Representative: Jody Whitney, Enbridge Representative, Dennis Esperance Method: Meeting / Consultation - In Person Meeting Public Synopsis: Jody Whitney, Jason Jensen, and Dennis Esperance met with Agency Chiefs Tribal Council representatives at the Coast Plaza Hotel in Calgary, Alberta, to discuss the business opportunities available on the Line 3 Replacement Program. JW provided an overview of the L3RP and the associated business opportunities. An Agency Chiefs Tribal Council representative provided an overview of their business capacity and partnerships, and indicated they would like to provide training for Agency Chiefs Tribal Council members between the ages of 18 and 24 years old. DE agreed to facilitate a follow-up meeting to establish a business relationship with the Agency Chiefs Tribal Council. Printed on October 5, 2015 Page 1 / 202 Enbridge Pipelines Inc. Quarter 3 Line 3 Replacement Program Aboriginal Engagement Log (June 15 - September 15, 2015) Line 3 Replacement Program Engagement Log Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation Aboriginal - First Nations Community Contact Date: Jul 09, 2015 14:00 Enbridge Representative: Jody Whitney, Enbridge Representative, Dennis Esperance Method: Meeting / Consultation - In Person Meeting Public Synopsis: Jody Whitney, Jason Jensen, and Dennis Esperance met with Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation representatives at Grey Eagle Resort located on Tsuu T'ina First Nation. An Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation representative informed Enbridge they were hosting evacuees who had been displaced as a result of forest fires in Saskatchewan and requested financial support to host the evacuees. -

Diabetes Directory

Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory February 2015 A Directory of Diabetes Services and Contacts in Saskatchewan This Directory will help health care providers and the general public find diabetes contacts in each health region as well as in First Nations communities. The information in the Directory will be of value to new or long-term Saskatchewan residents who need to find out about diabetes services and resources, or health care providers looking for contact information for a client or for themselves. If you find information in the directory that needs to be corrected or edited, contact: Primary Health Services Branch Phone: (306) 787-0889 Fax : (306) 787-0890 E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Saskatchewan Ministry of Health acknowledges the efforts/work/contribution of the Saskatoon Health Region staff in compiling the Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory. www.saskatchewan.ca/live/health-and-healthy-living/health-topics-awareness-and- prevention/diseases-and-disorders/diabetes Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................... - 1 - SASKATCHEWAN HEALTH REGIONS MAP ............................................. - 3 - WHAT HEALTH REGION IS YOUR COMMUNITY IN? ................................................................................... - 3 - ATHABASCA HEALTH AUTHORITY ....................................................... - 4 - MAP ............................................................................................................................................... -

Dmjohnson Draft Thesis Apr 1 2014(3)

“This Is Our Land!” Indigenous Rhetoric and Resistance on the Northern Plains by Daniel Morley Johnson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Comparative Literature University of Alberta © Daniel Morley Johnson, 2014 Abstract This thesis examines Indigenous rhetorics of resistance from the Treaty Six negotiations in 1876 to the 1930s. Using methods from Comparative Literature and Indigenous literary studies, the thesis situates the rhetoric of northern Plains Indigenous peoples in the context of settler-colonial studies, Indigenous literary nationalism, and Plains Indigenous concepts of nationhood and governance, and introduces the concept of rhetorical autonomy (an extension of literary nationalism) as an organizing framework. The thesis examines the ways Plains Indigenous writers and leaders have resisted settler-colonialism through both rhetorical and physical acts of resistance. Making use of archival and published works, the thesis is a literary and political history of Indigenous peoples from their origins on the northern plains to the period of political organizing after World War I. ii Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge and thank the Indigenous peoples of Treaty Six who have generously allowed me to live and work here in their territory: I hope this thesis honours your histories, is respectful of your stories, and can – in some small way – contribute to your futures. I am grateful to my doctoral committee for their support and guidance: my supervisor, Professor Jonathan Hart, and committee members and examiners, Professors Keavy Martin, Isabel Altamirano-Jiménez, Ellen bielawski, and Odile Cisneros. I am also grateful to Professor Priscilla Settee of the University of Saskatchewan for serving on my committee as external examiner. -

Emergency Response Exercise National Energy Board (“NEB”) Certificate OC-063

Adam Oswell Enbridge Sr Regulatory Advisor tel 587-233-6368 200, 425 – 1st Street SW Law, Regulatory Affairs fax 403-767-3863 Calgary, Alberta T2P 3L8 [email protected] Canada April 1, 2021 E-FILE Canada Energy Regulator Suite 210, 517 – 10th Avenue SW Calgary, AB T2E 0A8 Attention: Jean-Denis Charlebois, Secretary of the Commission Dear Mr. Charlebois, Re: Enbridge Pipelines Inc. (“Enbridge”) Line 3 Replacement Program (“Project”) Condition 35 – Emergency Response Exercise National Energy Board (“NEB”) Certificate OC-063 Condition 35 requires Enbridge to conduct both tabletop and equipment mobilization exercises in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. Condition 35 b) states the following: b) Provide the Board in writing, at least 45 days prior to the date of each emergency response exercise referred to in a), the following: i) location of the exercise; ii) exercise coordinator; iii) date of the exercise; iv) duration of the exercise; v) confirmation that a representative from each province (that is, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba) has been invited to participate in or observe the exercise; vi) the name and organization of each individual, including representatives from Aboriginal groups, invited to participate in the exercise; vii) type of exercise (that is, tabletop, or equipment deployment); and viii) goals (for example, focus of exercise, scope, scale, extent of play, format, evaluation method), and how success is measured. A full scale exercise will be held on May 19, 2021. The Incident Command Post will be organized virtually over Microsoft Teams. The equipment and field deployment will take place on the Souris River, in Wawanesa, MB. The exercise coordinator will be , Emergency Response Specialist, Prairie Region. -

Calling to Justice, 1St Annual Conference for Change

Calling to Justice, 1st Annual Conference for Change Presented by the Saskatchewan First Nations Women’s Commission MARCH 24-25-26, 2021 CALLING TO JUSTICE, 1ST ANNUAL CONFERENCE FOR CHANGE This March 24-26, the Saskatchewan First Nations Women’s Commission presents the first annual We Rise Conference, dedicated to advancing a regional action plan for change. In 2007, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) moved to enshrine the rights that “constitute the minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world.” In 2015, the Truth & Reconciliation Commission released 94 Calls to Action to redress the legacy of residential schools and advance reconciliation. Four years later, Reclaiming Power and Place: the Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls called for transformative legal and social changes to resolve the crisis that has devastated Indigenous communities across the country. Many First Nations people in Saskatchewan have shared their insight and experiences to build a better world for future generations. This three-day conference acknowledges our part in advocating for change, and that of our allies, and reflects on what we’ve accomplished so far, helping us to move forward to the next steps, together. A Red Eagle Lodge event, all associated proceeds from We Rise will be directed toward front-line programs and services for First Nations women, the keepers of the home fire, and devote resources to strategic goals including the advancement of Women’s Rights and Sovereignty. ONLINE DELIVERY: Due to COVID-19 restrictions, We Rise will be delivered in an online format through Webinar Ninja. -

5 Traditional Land and Resource Use

CA PDF Page 1 of 92 Energy East Project Part B: Saskatchewan and Manitoba Volume 16: Socio-Economic Effects Assessment Section 5: Traditional Land and Resource Use This section was not updated in 2015, so it contains figures and text descriptions that refer to the October 2014 Project design. However, the analysis of effects is still valid. This TLRU assessment is supported by Volume 25, which contains information gathered through TLRU studies completed by participating Aboriginal groups, oral traditional evidence and TLRU-specific results of Energy East’s aboriginal engagement Program from April 19, 2014 to December 31, 2015. The list of First Nation and Métis communities and organizations engaged and reported on is undergoing constant revision throughout the discussions between Energy East and potentially affected Aboriginal groups. Information provided through these means relates to Project effects and cumulative effects on TLRU, and recommendations for mitigating effects, as identified by participating Aboriginal groups. Volume 25 for Prairies region provides important supporting information for this section; Volume 25 reviews additional TRLU information identifies proposed measures to mitigate potential effects of the Project on TRLU features, activities, or sites identified, as appropriate. The TLRU information provided in Volume 25 reflects Project design changes that occurred in 2015. 5 TRADITIONAL LAND AND RESOURCE USE Traditional land and resource use (TLRU)1 was selected as a valued component (VC) due to the potential for the Project to affect traditional activities, sites and resources identified by Aboriginal communities. Project Aboriginal engagement activities and the review of existing literature (see Appendix 5A.2) confirmed the potential for Project effects on TLRU. -

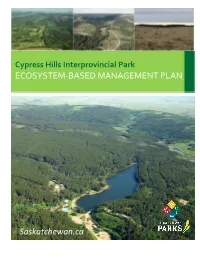

Ecosystem-Based Management Plan for Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park

Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park ECOSYSTEM-BASED MANAGEMENT PLAN Saskatchewan.ca Ecosystem-Based Management Plan February 19, 2020 Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park ECOSYSTEM-BASED MANAGEMENT PLAN PROJECT REFERENCE NUMBER: 1467-5 March 11, 2020 Revised: March 2021 Prepared for: Saskatchewan Ministry of Parks, Culture and Sport 3211 Albert St Regina, SK S4S 5W6 Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park Page | 1 Approval Form The Ecosystem-based Management Plan for Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park (2020) is hereby approved for use by the Ministry of Parks, Culture and Sport in the management of the ecosystem and landscape of Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park. March 11, 2020 Darryl Sande, RPF, Plan Author Date FORSITE Inc. Recommended for approval by: March 1, 2021 Thuan Chu, Senior Park Landscape Ecologist Date Landscape Protection Unit Ministry of Parks, Culture and Sport Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park Page | ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park (CHIPP) is a 183 square kilometre Natural Environment Park within the southwestern corner of Saskatchewan. The park encompasses the unique geological features and elevation of the Cypress Hills formation. The area contains a mix of Boreal and Montane forest elements as well as Prairie grassland elements. The area is surrounded by agricultural and pasture lands. The park is made up of a mix of natural forests and grasslands, which is classified into nine ecosites. Upland ecosites include plains rough fescue grassland on silty clay loam, lodgepole pine-dominated stands on sandy clay, white spruce stands on silty clay, aspen stands on clay loam, aspen-white spruce mixedwoods on silty clay soils, and aspen-lodgepole pine mixedwoods on clay loam. -

Analysis Report

Analysis Report WHETHER TO DESIGNATE THE NINE AGRICULTURAL DRAINAGE NETWORK PROJECTS IN SASKATCHEWAN December 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS PURPOSE ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 PROJECTS .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 CONTEXT OF REQUESTS ..................................................................................................................................... 2 PROJECT CONTEXT ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Project Overview ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Project Components and Activities ............................................................................................................... 5 Blackbird Creek Drainage Network (Red/Assiniboine River watershed) ........................................................... 5 Saline Lake Drainage Network (Upper Assiniboine River watershed) ............................................................... 6 600 Creek Drainage Network (Lower Souris River watershed) ......................................................................... 6 Vipond Drainage Network (Moose Mountain Lake and Lower Souris River watersheds)