Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preliminary Demographic Analysis of First Nations and Métis People

○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ APPENDIX F Preliminary Demographic Analysis of First Nations and Métis People A Background Paper Prepared for the Regina QuAppelle Health Region Working Together Towards Excellence Project September 2002 1. Introduction ........................................................................ 2 By Project Staff Team: Rick Kotowich 2. Findings Joyce Racette ........................................................................ 3 Dale Young The Size of the First Nations and Métis Alex Keewatin Populations ..................................................... 3 John Hylton The Characteristics of These Populations....... 6 The Trends ...................................................... 8 3. Conclusion ........................................................................ 9 Appendix F 1 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 1. Introduction 2. It has been well documented that even in the CMAs where census data is available, it often significantly underestimates the true size of the Aboriginal Regina Qu’Appelle Health Region population. This occurs for many reasons, including the fact that Aboriginal people tend to fill out fewer The purpose of this brief paper is to provide a census forms. Moreover, conventional methods for preliminary analysis of available population and estimating the gap in reporting do not always take demographic data for the First Nations and Métis account of the larger size of Aboriginal people who live within the geographic -

Kakisiwew Final Written Arguments

Court File No. T-2155-00 FEDERAL COURT – TRIAL DIVISION BETWEEN: WESLEY BEAR, FREIDA SPARVIER, JANET HENRY, FREDA ALLARY, ROBERT GEORGE, AUDREY ISAAC, SHIRLEY FLAMONT, KELLY MANHAS, MAVIS BEAR and MICHAEL KENNY, on their own behalf and on behalf of all other members of the KAKISIWEW INDIAN BAND, Plaintiffs, - and - HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN IN RIGHT OF CANADA, as represented by THE MINISTER OF INDIAN AND NORTHERN AFFAIRS and THE OCHAPOWACE INDIAN BAND NO. 71, Defendants. Court File No.: T-2153-00 FEDERAL COURT – TRIAL DIVISION BETWEEN: PETER WATSON, SHARON BEAR, CHARLIE BEAR, WINSTON BEAR and SHELDON WATSON, being the Heads of Family of the direct descendants of the Chacachas Indian Band, representing themselves and all other members of the CHACACHAS INDIAN BAND, Plaintiffs, - and - HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN IN RIGHT OF CANADA, as represented by THE MINISTER OF INDIAN AND NORTHERN AFFAIRS CANADA and THE OCHAPOWACE FIRST NATION, Defendants. FINAL WRITTEN REPRESENTATIONS On behalf of the Plaintiffs Wesley Bear et al. BOUDREAU LAW Barristers & Solicitors 100-1619 Pembina Highway Winnipeg, MB R3T 3Y6 Phone: 204-318-2688 Facsimile: 204-477-6057 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Overview 2 Part I FACTS 2 Part II POINTS OF ISSUE 13 Part III SUBMISSIONS 13 Part IV ORDER SOUGHT 50 Part V LIST OF AUTHORITIES 52 1 OVERVIEW 1. This final submission is provided on behalf of the Plaintiffs Wesley Bear et al. (the “Bear” or “Kakisiwew” plaintiffs) in Court Action T-2155-00. 2. The Kakisiwew Indian Band was a recognized Band under Treaty 4 and the Indian Act, (1876). Chief Kakisiwew was the first to put his mark on Treaty 4 on September 15, 1874. -

Local Alberta Treaties, Metis Nation of Alberta Regions, Metis Settlements, and Indigenous Nations Acknowledgements

Local Alberta Treaties, Metis Nation of Alberta Regions, Metis Settlements, and Indigenous Nations Acknowledgements Prepared for the Alberta Council of Women’s Shelters and their members by Lewis Cardinal, March 2018 Contents ACWS Acknowledgments 4 Traditional Land Acknowledgments 4 On Reserve Member Recognition 4 Why we do Treaty Acknowledgments 5 Local Alberta Treaties, Metis Nation of Alberta Regions, Metis Settlements, and Indigenous Nations Acknowledgements 6 Banff 6 Bow Valley Emergency Shelter 6 Brooks 6 Cantera Safe House 6 Calgary 6 Kerby Rotary Shelter 6 YWCA Sheriff King Home 6 The Brenda Strafford Centre for the Prevention of Domestic Violence 7 Discovery House 7 Sonshine Centre 7 Calgary Women’s Emergency Shelter 7 Camrose 8 Camrose Women’s Shelter 8 Cold Lake 8 Dr. Margaret Savage Crisis Centre 8 Joie’s Phoenix House 8 Edmonton 8 SAGE Senior’s Safe House 8 WIN House 9 Lurana Shelter 9 La Salle 9 Wings of Providence 10 Enilda 10 Next Step 10 Sucker Creek Emergency Women’s Shelter 10 Fairview 10 Crossroads Resource Centre 10 Wood Buffalo Region 11 Wood Buffalo Second Stage Housing 11 Unity House 11 Grande Cache 11 Grande Cache Transition House 11 Grande Prairie 11 Odyssey House 11 Serenity Place 12 High Level 12 Safe Home 12 High River 12 2 | Page Rowan House Emergency Shelter 12 Hinton 12 Yellowhead Emergency Shelter 12 Lac La Biche 13 Hope Haven Emergency Shelter 13 Lynne’s House 13 Lethbridge 13 YWCA Harbour House 13 Lloydminster 13 Dolmar House 13 Lloydminster Interval Home 14 Maskwacis 14 Ermineskin Women’s Shelter 14 Medicine Hat 14 Musasa House 14 Phoenix Safe House 14 Morley 14 Eagle’s Nest Stoney Family Shelter 14 Peace River 15 Peace River Regional Women’s Shelter 15 Pincher Creek 15 Pincher Creek Women’s Emergency Shelter 15 Red Deer 15 Central Alberta Women’s Emergency Shelter 15 Rocky Mountain House 15 Mountain Rose Women’s Shelter 15 Sherwood Park 16 A Safe House 16 Slave Lake 16 Northern Haven Women’s Shelter 16 St. -

Treaties in Canada, Education Guide

TREATIES IN CANADA EDUCATION GUIDE A project of Cover: Map showing treaties in Ontario, c. 1931 (courtesy of Archives of Ontario/I0022329/J.L. Morris Fonds/F 1060-1-0-51, Folder 1, Map 14, 13356 [63/5]). Chiefs of the Six Nations reading Wampum belts, 1871 (courtesy of Library and Archives Canada/Electric Studio/C-085137). “The words ‘as long as the sun shines, as long as the waters flow Message to teachers Activities and discussions related to Indigenous peoples’ Key Terms and Definitions downhill, and as long as the grass grows green’ can be found in many history in Canada may evoke an emotional response from treaties after the 1613 treaty. It set a relationship of equity and peace.” some students. The subject of treaties can bring out strong Aboriginal Title: the inherent right of Indigenous peoples — Oren Lyons, Faithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation’s Turtle Clan opinions and feelings, as it includes two worldviews. It is to land or territory; the Canadian legal system recognizes title as a collective right to the use of and jurisdiction over critical to acknowledge that Indigenous worldviews and a group’s ancestral lands Table of Contents Introduction: understandings of relationships have continually been marginalized. This does not make them less valid, and Assimilation: the process by which a person or persons Introduction: Treaties between Treaties between Canada and Indigenous peoples acquire the social and psychological characteristics of another Canada and Indigenous peoples 2 students need to understand why different peoples in Canada group; to cause a person or group to become part of a Beginning in the early 1600s, the British Crown (later the Government of Canada) entered into might have different outlooks and interpretations of treaties. -

For More Information Or to Contact the Committee, Please Visit Iamc-Line3.Com

December 10, 2019 Re: Advice to Government and the CER from Indigenous Members of the Line 3 IAMC Dear Minister O’Regan, On behalf of the Indigenous Committee members of the Line 3 Indigenous Advisory and Monitoring Committee (IAMC), we would like to congratulate you on your appointment as Minister of Natural Resources. Since 2017, the Line 3 IAMC has been hard at work implementing our mandate and drawing on our shared experience to develop advice for the federal government and the Canada Energy Regulator (CER). We are pleased to provide our Advice to the Government of Canada and the CER which was recently approved by a majority of Indigenous Committee members. We look forward to working with you on the advice, and would like to extend an invitation for you and your staff to meet the Committee in the new year. The mandate of the IAMC is to integrate Indigenous perspectives into the monitoring and regulatory oversight of the Line 3 Replacement Program (L3RP), and provide recommendations to the federal government and regulator. The Committee brings together 16 Indigenous and two senior federal representatives to monitor the L3RP, and to provide advice to government and regulators. Committee members have a shared goal of safety and protection of environmental and Indigenous interests along the Line 3 corridor over the lifecycle of the project. As per clause 15 of the Committee’s Terms of Reference, advice supported by the majority of members may be put forward provided that all Committee members were provided with an opportunity to explain, in writing, why they could not support the advice. -

Environmental Overview

Vantage Pipeline Project Environmental and Socio-Economic Assessment Section 18: Traditional Knowledge Study Table 18-1 Legislation, Guidelines and Policies Related to First Nation and Métis Consultation REGULATORY GUIDELINES, PERMITS, GOVERNMENT AGENCIES LEGISLATION POLICIES Government of Alberta Various Various Guidelines are set out in Alberta’s First Nations Consultation Guidelines on Land Management and Resource Development (2007) Government of Various Various Guidelines are set out First Saskatchewan Nation and Métis Consultation Policy Framework June 2010 (2010) Federal Various The NEB Act Guidelines set out in (Government of Aboriginal Consultation Canada 1985) and Accommodation: CEAA Interim Guidelines for (Government of Federal Officials to Fulfill Canada 1992) the Legal Duty to Consult (2008) Aboriginal engagement and a TKS is a required by the NEB under the CEAA 18.2 Cultural and Historical Setting Individual Aboriginal consultation and TKS are part of a larger political, historical, and cultural framework which is unique for each First Nation and Métis community (Frideres and Krosenbrink-Gelissen 1998, Dickason 2010). Consultation often takes place between communities with very different worldviews and political histories. Recognizing this context is key to successful consultation which can benefit Aboriginal groups and other stakeholders. 18.3 Participating Aboriginal Groups Identifying Aboriginal groups which may be impacted by the Project is difficult. Proximity of the proposed right-of-way (ROW) to reserves or communities cannot be the only measure as it may not engage all interested communities given the modern political landscape does not fully reflect traditional land use. Prior to the signing of treaties and the reserve system, Aboriginal groups had much larger areas of traditional land use (Binnema 2001, Peck 2010). -

White Bear First Nations' Participation in World Wars

boundaries eh; just a territory which was Sioux or Cree and you couldn’t go west because the Blackfoot were controlling the foothills and mountain areas. That’s my understanding (WBFNs Elder George Sparvier, 2012). That was the Riel Rebellion. The paranoia of the soldiers and the people; they sent them down here. Grandfather was registered in Turtle Mountain. (During the Riel Rebellion) They didn’t want them to get involved in the Riel Rebellion (WBFNs Elder Almer Standingready, 2012). Especially the young men. So a number of them went down (to Turtle Mountain) (WBFNs Elder Phyllis Gibson, 2012) Upon the end of this rebellion, the Government of Canada convicted 19 Métis and 33 natives of offenses related to the uprising. Ironically, only a few Métis were hanged but Canadians witnessed a mass hanging of non-Métis native people who participated in the rebellion. Cree Chiefs Big Bear, Poundmaker, and One Arrow were each found guilty of treason-felony, and sentenced to three years in Stoney Mountain Penitentiary. A fourth Chief, the Dakota leader White Cap, was acquitted of charges despite being a member of Riel’s Exovedate9 Council (Canadian Encyclopedia, 2012). After the Northwest/ Riel Rebellion the Government instituted a series of repressive policies against the indigenous peoples. These measures, which went against the spirit of the treaties, included forcible confinement to Reserves, the dismantling of aboriginal culture and the removal of children to residential schools for assimilation (Stonechild, 2007). These measures were in stark contrast to the results of the first resistance in Manitoba and had deep and lasting effects upon indigenous peoples in Canada including the White Bear First Nations, despite the fact that White Bear did not participate in the Rebellion. -

BITTERNOSE-THESIS.Pdf (1.420Mb)

KIHCI-ASOTAMÂTOWIN (THE TREATY SOVEREIGNS’ SACRED AGREEMENTS) AND THE CROWN’S CONSTITUTIONAL OBLIGATIONS TO HOLDERS OF TREATY RIGHTS THROUGH CONSULTATION AND RESTORATION OF TREATY CONSTITUTIONALISM. 1 A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Masters of Laws In the College of Law University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Leah M. Bitternose April 2014 © Copyright Leah M. Bitternose, 2014. All Rights Reserved 1 Treaty 3 Medallion signed on October 3, 1873 between the Saulteaux, Ojibway Nations and the Crown depicting Kihci-Asotamâtowin, The Treaty Sovereigns’ Sacred Undertakings to each other with the enduring symbolism of the sun shining, the grass growing and the river flowing. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirement for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my thesis work, or, in his absence, by the Dean of the College of Law. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Dean of the College of Law 15 Campus Drive University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7N 5A6 Canada i ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to assess the Crown’s Constitutional duty of consultation and its application on the holders of Treaty rights. -

Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory

Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory September 2017 CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory September 2017 The following document offers the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) recommended territorial acknowledgement for institutions where our members work, organized by province. While most of these campuses are included, the list will gradually become more complete as we learn more about specific traditional territories. When requested, we have also included acknowledgements for other post-secondary institutions as well. We wish to emphasize that this is a guide, not a script. We are recommending the acknowledgements that have been developed by local university-based Indigenous councils or advisory groups, where possible. In other places, where there are multiple territorial acknowledgements that exist for one area or the acknowledgements are contested, the multiple acknowledgements are provided. This is an evolving, working guide. © 2016 Canadian Association of University Teachers 2705 Queensview Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K2B 8K2 \\ 613-820-2270 \\ www.caut.ca Cover photo: “Infinity” © Christi Belcourt CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples and Traditional Territory September 2017 Contents 1| How to use this guide Our process 2| Acknowledgement statements Newfoundland and Labrador Prince Edward Island Nova Scotia New Brunswick Québec Ontario Manitoba Saskatchewan Alberta British Columbia Canadian Association of University Teachers 3 CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples and Traditional Territory September 2017 1| How to use this guide The goal of this guide is to encourage all academic staff context or the audience in attendance. Also, given that association representatives and members to acknowledge there is no single standard orthography for traditional the First Peoples on whose traditional territories we live Indigenous names, this can be an opportunity to ensure and work. -

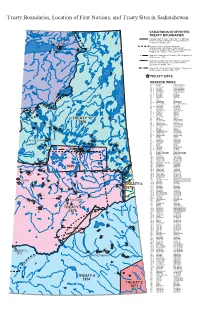

Treaty Boundaries Map for Saskatchewan

Treaty Boundaries, Location of First Nations, and Treaty Sites in Saskatchewan VARIATIONS IN DEPICTED TREATY BOUNDARIES Canada Indian Treaties. Wall map. The National Atlas of Canada, 5th Edition. Energy, Mines and 229 Fond du Lac Resources Canada, 1991. 227 General Location of Indian Reserves, 225 226 Saskatchewan. Wall Map. Prepared for the 233 228 Department of Indian and Northern Affairs by Prairie 231 224 Mapping Ltd., Regina. 1978, updated 1981. 232 Map of the Dominion of Canada, 1908. Department of the Interior, 1908. Map Shewing Mounted Police Stations...during the Year 1888 also Boundaries of Indian Treaties... Dominion of Canada, 1888. Map of Part of the North West Territory. Department of the Interior, 31st December, 1877. 220 TREATY SITES RESERVE INDEX NO. NAME FIRST NATION 20 Cumberland Cumberland House 20 A Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 B Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 C Muskeg River Cumberland House 20 D Budd's Point Cumberland House 192G 27 A Carrot River The Pas 28 A Shoal Lake Shoal Lake 29 Red Earth Red Earth 29 A Carrot River Red Earth 64 Cote Cote 65 The Key Key 66 Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 66 A Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 68 Pheasant Rump Pheasant Rump Nakota 69 Ocean Man Ocean Man 69 A-I Ocean Man Ocean Man 70 White Bear White Bear 71 Ochapowace Ochapowace 222 72 Kahkewistahaw Kahkewistahaw 73 Cowessess Cowessess 74 B Little Bone Sakimay 74 Sakimay Sakimay 74 A Shesheep Sakimay 221 193B 74 C Minoahchak Sakimay 200 75 Piapot Piapot TREATY 10 76 Assiniboine Carry the Kettle 78 Standing Buffalo Standing Buffalo 79 Pasqua -

Dradt 2019 Muscowpetung Constitution

Muscowpetung Saulteaux First Nation Constitution Short Title This legislation may be cited as the Muscowpetung Saulteaux First Nation Constitution Preamble Preamble Muscowpetung Saulteaux First Nation signed Treaty 4 with representatives of Her Majesty the Queen of the British Crown as a sovereign Nation and occupier of lands now identified as Treaty 4 territory and other ancestral lands. We the people of Muscowpetung Saulteaux First Nation assert our inherent and sovereign right to self- government and self• determination as we have done since time immemorial. This Constitution shall govern our lands and territories, the establishment of self-governing laws and frameworks for justice, liberty, peace and order, lands, resources, minerals and good governance. This Constitution shall protect and encourage the fundamental principles of Muscowpetung Saulteaux First Nation including, our natural and traditional laws, culture, language, traditions, heritage, history, peace, order, good governance and our sovereign Treaty relationship with the British Crown. Article One Assertion of Sovereignty 1.01 Muscowpetung Saulteaux First Nation hereby asserts its sovereignty and the right to exercise its inherent jurisdiction to govern its affairs, lands, resources and Citizens. Sovereignty Article Two Fundamental Rights & Freedoms 2.01 Citizens shall, without hindrance, enjoy equality, treaty rights, freedom of worship, culture, conscience, speech, assembly, press, association, and the right to due General process subject to reasonable limits founded in a free and democratic society and the Rights cultural values and teachings of Muscowpetung Saulteaux First Nation. 2.02 Citizens have equal opportunity to participate in all programs and services of the Muscowpetung Saulteaux First Nation subject to reasonable limitations, and have Special rights specific to persons identified as Citizens in legislation of Muscowpetung Rights Saulteaux First Nation passed from time to time. -

Emergency Response Exercise National Energy Board (“NEB”) Certificate OC-063

Adam Oswell Enbridge Sr Regulatory Advisor tel 587-233-6368 200, 425 – 1st Street SW Law, Regulatory Affairs fax 403-767-3863 Calgary, Alberta T2P 3L8 [email protected] Canada April 1, 2021 E-FILE Canada Energy Regulator Suite 210, 517 – 10th Avenue SW Calgary, AB T2E 0A8 Attention: Jean-Denis Charlebois, Secretary of the Commission Dear Mr. Charlebois, Re: Enbridge Pipelines Inc. (“Enbridge”) Line 3 Replacement Program (“Project”) Condition 35 – Emergency Response Exercise National Energy Board (“NEB”) Certificate OC-063 Condition 35 requires Enbridge to conduct both tabletop and equipment mobilization exercises in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. Condition 35 b) states the following: b) Provide the Board in writing, at least 45 days prior to the date of each emergency response exercise referred to in a), the following: i) location of the exercise; ii) exercise coordinator; iii) date of the exercise; iv) duration of the exercise; v) confirmation that a representative from each province (that is, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba) has been invited to participate in or observe the exercise; vi) the name and organization of each individual, including representatives from Aboriginal groups, invited to participate in the exercise; vii) type of exercise (that is, tabletop, or equipment deployment); and viii) goals (for example, focus of exercise, scope, scale, extent of play, format, evaluation method), and how success is measured. A full scale exercise will be held on May 19, 2021. The Incident Command Post will be organized virtually over Microsoft Teams. The equipment and field deployment will take place on the Souris River, in Wawanesa, MB. The exercise coordinator will be , Emergency Response Specialist, Prairie Region.