Identity and Multiplicity in Canetti's and Wagenstein's Birthplaces: Exploring the Rhizomatic Roots of Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Interest Table of Contents

OTHER PRESS JEWISH INTEREST TABLE OF CONTENTS UPCOMING 4 Nuestra América 4 by Claudio Lomnitz, translated by John Cullen Publication Date: 02/09/2021 Proustian Uncertainties 4 by Saul Friedländer Publication Date: 12/01/2020 JEWISH INTEREST 5 What You Did Not Tell 5 by Mark Mazower When Memory Comes 5 by Saul Friedländer, translated by Helen R. Lane Where Memory Leads 5 by Saul Friedländer A Brief Stop on the Road From Auschwitz 5 by Göran Rosenberg The Road to Rescue 5 by Mietek Pemper The Bell of Treason 6 by P. E. Caquet For Two Thousand Years 6 by Mihail Sebastian, translated by Philip Ó Ceallaigh The Brothers Ashkenazi 6 by I. J Singer The Witness House 6 by Christiane Kohl The Woman from Hamburg 7 by Hanna Krall Isaac’s Torah 7 by Angel Wagenstein, translated by Elizabeth Frank and Deliana Simeonova Farewell, Shanghai 7 by Angel Wagenstein, translated by Elizabeth Frank and Deliana Simeonova Stalemate 7 by Icchokas Meras and Jonas Zdanys The Impossible Exile 7 by George Prochnik A Guest in My Own Country 8 by George Konrad Stranger in a Strange Land 8 by George Prochnik Putnam Camp 8 by George Prochnik 2 The Sun and Her Stars 8 by Donna Rifkind And in the Vienna Woods the Trees Remain 8 By Elisabeth Åsbrink; translated by Saskia Vogel Hitler, My Neighbor 9 by Edgar Feuchtwanger and Bertil Scali, translated by Adriana Hunter Hurry Down Sunshine 9 by Michael Greenberg Beg, Borrow, Steal 9 by Michael Greenberg Departures 9 by Paul Zweig ISRAELI SOCIETY AND LITERATURE 10 Walled 10 by Sylvain Cypel, senior journalist from le Monde Breaking -

Imagens Para O Futuro O Cinema Da Alemanha Oriental

3 4 5 imagens para o futuro O CINEMA DA ALEMANHA ORIENTAL 31 JUL A 19 AGO DE 2018 8 9 ÍNDICE 13 A DEFA Robin Mallick 17 ENTRE IMAGENS E UTOPIAS Pedro Henrique Ferreira e Thiago Brito 23 DEFA: UM RESUMO HISTÓRICO Séan Allan 46 RESGATADO EM VÃO Thomas Elsaesser 71 A DESCOBERTA DO ORDINÁRIO Joshua Feinstein 117 OS FILMES PROIBIDOS Daniela Berghahn 131 SOBRE AS POSSIBILIDADES DE UMA ARTE CINEMATOGRÁFICA SOCIALISTA Konrad Wolf 140 ANDANDO NA CORDA BAMBA SOBRE TERRITÓRIO PROIBIDO Andrea Rinke 154 POR DETRÁS DAS CORTINAS DE UMA INDÚSTRIA CINEMATOGRÁFICA ESTATAL Margrit Frölich 180 ASSINCRONIA NO ÚLTIMO FILME DA DEFA Reinhild Steingröver 217 10 PERGUNTAS PARA EVELYN SCHMIDT Thiago Brito e Pedro Henrique Ferreira 222 DEFA: UMA VISÃO PESSOAL Wolfgang Kohlhaase 237 POSTERS 263 MINI-BIOS 270 SINOPSES 12 A DEFA Robin Mallick1 Depois que a DEFA teve que cancelar suas atividades, devido à unificação alemã em 1990, muitos dos filmes produzidos por ela foram esquecidos, até mesmo na Alemanha. Ao mesmo tempo, várias obras fazem sucesso até hoje em dia. O filme da DEFA de mais sucesso desde sua estreia em 1973 (com mais de 3 milhões de espectadores) até hoje é A lenda de Paul e Paula2. Heiner Carow conseguiu capturar no seu filme uma sensação de vida que não só impressionou o público dos anos 70, mas que prende os espectadores de quase todos os tempos. Seu filme Coming Out3 também marcou a história do cinema: a trama de um professor jovem que descobre sua homossexualidade não só quebrou vários tabus, mas também teve sua estreia em Berlim Oriental no dia 9 de novembro de 1989, dia da queda do Muro. -

L'homme, Band 26,2 (2015)

L’Homme. Z. F. G. 26, 2 (2015) Forum The Female Body of Jewish Suffering: The Cinematic Recreation of the Holocaust in the Bulgarian-East German Co-Production “Zvezdi/Sterne” (1959) Nadège Ragaru Distancing itself from earlier studies, recent scholarship on the cinematic representa- tion of the Holocaust has demonstrated that the portrayal of anti-Jewish persecution has not remained taboo throughout the socialist era in Eastern Europe.1 A segment of this scholarly literature has explored the gendered dimensions of the filmic rendering of Jewish victimhood and agency in Eastern Europe. In a recent contribution, for instance, Anke Pinkert has investigated the changing depictions of Jewish manhood in GDR cinema with a view to “re-examin[ing] discourses of victimisation and perpetration”.2 Focusing on the interpretation of womanhood in film, the present arti- cle aims to contribute to the growing body of literature by tracing the inception, mak- ing, and reception of “Zvezdi/Sterne” (Stars), a Bulgarian-East German co-production directed by Konrad Wolf. The film, which was awarded the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Festival in 1959, tells the story of an impossible love between a German Unter- offizier and a Greek Jewish woman who was detained with other Jews from Bulgarian- occupied Western Thrace in a Bulgarian transit camp, pending deportation to Poland. 1 On the Soviet case cf. Jeremy Hicks, First Films of the Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and the Genocide of the Jews, 1938–1946, Pittsburgh 2012; on the GDR, in an abundant literature, cf. Daniela Berghahn, Hollywood behind the Wall: The Cinema of East Germany, Manchester 2005; Christiane Mückenberger, The Anti-Fascist Past in DEFA Films, in: Seán Allan and John Sandford eds., DEFA: East German Cinema, 1946–1992, New York 2003, 58–76. -

Soviet Science Fiction Movies in the Mirror of Film Criticism and Viewers’ Opinions

Alexander Fedorov Soviet science fiction movies in the mirror of film criticism and viewers’ opinions Moscow, 2021 Fedorov A.V. Soviet science fiction movies in the mirror of film criticism and viewers’ opinions. Moscow: Information for all, 2021. 162 p. The monograph provides a wide panorama of the opinions of film critics and viewers about Soviet movies of the fantastic genre of different years. For university students, graduate students, teachers, teachers, a wide audience interested in science fiction. Reviewer: Professor M.P. Tselysh. © Alexander Fedorov, 2021. 1 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 1. Soviet science fiction in the mirror of the opinions of film critics and viewers ………………………… 4 2. "The Mystery of Two Oceans": a novel and its adaptation ………………………………………………….. 117 3. "Amphibian Man": a novel and its adaptation ………………………………………………………………….. 122 3. "Hyperboloid of Engineer Garin": a novel and its adaptation …………………………………………….. 126 4. Soviet science fiction at the turn of the 1950s — 1960s and its American screen transformations……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 130 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….… 136 Filmography (Soviet fiction Sc-Fi films: 1919—1991) ……………………………………………………………. 138 About the author …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 150 References……………………………………………………………….……………………………………………………….. 155 2 Introduction This monograph attempts to provide a broad panorama of Soviet science fiction films (including television ones) in the mirror of -

National Endowment for the Humanities Grant Awards and Offers, December 2010

OFFICE OF COMMUNICATIONS 1100 PENNSYLVANIA AVE., NW WASHINGTON, D.C. 20506 (202)606-8446 WWW.NEH.GOV NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES GRANT AWARDS AND OFFERS, DECEMBER 2010 Note: Projects that are part of the We the People program, which encourages and strengthens the teaching, study, and understanding of American history and culture, are denoted by an asterisk. ALABAMA (2) $12,000 Birmingham Birmingham Museum of Art Outright: $6,000 [Preservation Assistance Grants] Project Director: Melissa Mercurio Project Title: Rehousing of the Buten Wedgwood Collection Project Description: Purchase of storage equipment to rehouse the Buten Wedgwood Collection, which consists of almost 8,000 pieces of ceramics dating from the inception of the Wedgwood Company in 1759 through the 1980s. Harry and Nettie Buten began collecting Wedgwood in 1931 and opened their museum in Merion, Pennsylvania, to the public in 1957. The collection, which includes some of the most unique Wedgwood wares, was acquired by the Birmingham Museum of Art in 2008, a gift from the Buten family through the Wedgwood Society of New York. Montevallo University of Montevallo Outright: $6,000 [Preservation Assistance Grants] Project Director: Carey Heatherly Project Title: Continued Improvement of the University of Montevallo's University Archives and Special Collections Project Description: The purchase of preservation supplies to provide better care for the Carmichael Library's archives and special collections, documenting the history of the university and women's education in Alabama. The archive includes a collection of dolls created by the Works Progress Administration's Alabama Visual Education Project and the Olmstead Brothers' original design for the campus, a designated National Historic District. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION “Can we Europeans still entertain? Can we think in the dimensions of a global culture? . The fi rst who has a vision of the fi lm of the future, to him belongs BABELSBERG!”1 With this bold statement in 1992, Volker Schlöndorff, an acclaimed cineaste born in West Germany (the Federal Republic of Germany, or FRG; hereafter West Germany or FRG), invited European artists to take over the studios near Berlin. The same stu- dios had housed the now defunct East German state-run fi lm company, Deutsche Film-Aktiengesellschaft (DEFA; 1946–92) and before that, one of the largest motion picture industries on the continent, Universum Film-Aktiengesellschaft (UFA; 1917–45). As Babelsberg’s managing di- rector (1992–97), Schlöndorff had avowed earlier in his statement: “To me, the name DEFA has no color or odor. Like the name UFA, it belongs to history and to an era that is not mine. It should continue to live in history as a name.”2 This text and later interviews stirred a larger de- bate about the dismantling of DEFA right after the collapse of East Ger- many (the German Democratic Republic, or GDR; hereafter either East Germany or GDR)—a controversy in which hundreds of fi lmmakers and crew members were dismissed from their job because they were viewed as obsolete in a newly transformed industry. In what became known as the public battle for Babelsberg, former DEFA employees largely decried Schlöndorff’s failure to recognize how much they had in common with their Western counterparts, particularly in regard to their contribution to -

Monthly for the Promotion of Jewish Culture

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 16 09.00/09.30 Registration 09.30/10.00 Opening Notes Vice Rector Peter Riedler Dean of Studies of the Faculty of Humanities Margit Reitbauer Heads of the Institutes of Slavic Studies and Jewish Studies, Organizers 10.00/11.30 I IMPERIAL EXPERIENCES, ENTANGLEMENTS AND ENCOUNTERS KNOWLEDGE AND CULTURE THROUGH HISTORY Chair: Mirjam Rajner KARKASON, TAMIR The “Entangled Histories” of the Jewish Enlightenment in Ottoman Southeastern Europe ŠMID, KATJA Amarachi’s and Sasson’s Musar Ladino Work Sefer Darkhe ha-Adam. Between Reality and Intertextuality KEREM, YITZCHAK Albertos Nar, from Historian to Author and Ethnographer. Crossing from Salonikan Sephardic Historian to Greek Prose, Fiction, Social Commentary and Tracing Greek Influences on Salonikan and Izmir Sephardic Culture 11.30/12.00 Break 12.00/13.00 PERCEIVING THE SELF AND THE OTHER Chair: Željka Oparnica GRAZI, ALESSANDRO On the Road to Emancipation. Isacco Samuele Reggio’s Jewish and Italian Identity in 19th-century Gorizia Milovanovič, Stevan The Images of Sephardim in the Travel Book Oriente by Vicente Blasco Ibáñez 13.00/15.00 Lunch 15.00/16.30 POSTIMPERIAL EXPERIENCES Chair: Sonja Koroliov OSTAJMER, BRANKO Mavro Špicer (1862—1936) and His Views on the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy JURLINA, PETRA Small Town Elegy: Shaping and Guarding Memory in Rural Croatia. The Case of Vinica, Lepavina and Slatinski Drenovac SELVELLI, GIUSTINA The Multicultural Cities of Plovdiv and Ruse Through the Eyes of Elias Canetti and Angel Wagenstein. Two “Post-Ottoman” Jewish Writers 16.30/17.00 -

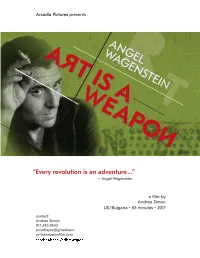

Pressive and Corrupt Regimes

facebook.com/artisaweapon ! ANGEL WAGENSTEIN: ART IS A WEAPON ! Synopsis ! ! “Angel Wagenstein’s life and work are a secret history of the tweneth century.” ! Elizabeth Frank ! This provocave documentary portrait of the Bulgarian Jewish film arst Angel Wagenstein introduces Western viewers to a brilliant and charisma,c storyteller, for whom art became a form of resistance against a series of oppressive and corrupt regimes. At 94, Wagenstein remains a passionate witness to history, and an acve parcipant in the polical debate on Europe’s rocky post-communist future. Wagenstein’s improbably adventurous life story includes command of a daredevil Jewish par,san brigade in WW2, early dreams of a socialist utopia, furious disappointment when those dreams began to crumble, and a central role in the democra,c reforms that ended communist rule in Bulgaria. But his most striking quality as a documentary subject -- in addion to his ferocious intelligence and massive charm -- is his willingness to think crically about whatever historical situaon he is placed in, !rather than succumb to the tempta,ons of ideological purity. ART IS A WEAPON explores many of Wagenstein’s beauful and deeply ironic films, focusing in parcular on STERNE (“STARS”), his autobiographical masterpiece, which beat Hiroshima Mon Amour and The 400 Blows to take the Special Jury prize at Cannes in 1959. STARS details an inially indifferent German soldier’s reluctant awakening to how he is personally implicated in the horror of what is happening to Europe’s Jews. It also brings to life a neglected chapter of Jewish resistance that !challenges toxic myths of Jewish passivity during the Shoah. -

New German Critique, No. 49, Special Issue on Alexander

new critiquegqrpian I L Number49 Winter1990 SPECIAL ISSUE ON ALEXANDER KLUGE AlexanderKluge The Assaultof the Presenton the Restof Time EricRentschler RememberingNot to Forget: A RetrospectiveReading of Kluge'sBrutality in Stone TimothyCorrigan The Commerceof Auteurism:a Voice withoutAuthority HelkeSander "You Can't AlwaysGet WhatYou Want": The Filmsof AlexanderKluge HeideSchliipmann Femininityas ProductiveForce: Kluge and CriticalTheory GertrudKoch AlexanderKluge's Phantomof the Opera AlexanderKluge On Opera, Filmand Feelings RichardWolin On MisunderstandingHabermas: A Responseto Rajchman JohnRajchman Rejoinder to Richard Wolin Marc Silberman Remembering History:The Filmmaker Konrad Wolf This content downloaded on Fri, 18 Jan 2013 09:51:49 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions NEW GERMAN an interdisciplinary journal of german studies CRITIQUE Editors:David Bathrick(Ithaca), Helen Fehervary(Columbus), Miriam Hansen (Chicago), AndreasHuyssen (New York),Anson Rabinbach (New York),Jack Zipes (Minneapolis). ContributingEditors: Leslie Adelson (Columbus), Geoff Eley (AnnArbor), Ferenc Feher (New York),Agnes Heller (New York),Peter U. Hohendahl(Ithaca), Douglas Kellner (Austin),Eberhard Kn6dler-Bunte (Berlin), Sara Lennox (Amherst),Andrei Markovits (Cambridge),Biddy Martin (Ithaca), Rainer Naigele (Baltimore),Eric Rentschler (Irvine),Henry Schmidt (Columbus), James Steakley (Madison). AssistantEditors: Ned Brinkley(Ithaca), and Karen Kenkel(Ithaca). ProjectAssistant: Cynthia Herrick (Ithaca). Publishedthree times a yearby TELOS PRESS, 431 E. 12thSt., New York,NY 10009. NewGerman Critique No. 49 correspondsto Vol. 17,No. 1. ? New GermanCritique Inc. 1990.All rightsreserved. New GermanCritique is a non-profit,educational organiza- tionsupported by theDepartment of GermanLiterature of CornellUniversity and by a grantfrom the Departmentof Germanand College of Humanitiesof Ohio State University. All editorialcorrespondence should be addressedto: NEW GERMAN CRITIQUE, Departmentof GermanStudies, 185 GoldwinSmith Hall, CornellUniversity, Ithaca, New York 14853. -

The Gendered Dimensions of "Zvezdi/Sterne" (1959)

The gendered dimensions of "Zvezdi/Sterne" (1959) On the Bulgarian-East German co-production of Konrad Wolf's Holocaust film Nadège Ragaru 27 January 2016 As part of a special focus in "L'homme" on gender and Cold War visual cultures, Nadège Ragaru goes behind the scenes of Konrad Wolf's feature film "Zvezdi/Sterne", to look at how the film's Bulgarian and German partners conceived of the "Jewish catastrophe" and imagined gender roles. Distancing itself from earlier studies, recent scholarship on the cinematic representation of the Holocaust has demonstrated that the portrayal of anti-Jewish persecution did not remain taboo throughout the socialist era in eastern Europe. [1] A segment of this scholarly literature has explored the gendered dimensions of the filmic rendering of Jewish victimhood and agency in eastern Europe. In a recent contribution, for instance, Anke Pinkert has investigated the changing depictions of Jewish manhood in GDR cinema with a view to “re-examin[ing] discourses of victimization and perpetration”. [2] Focusing on the interpretation of womanhood in film, the present article aims to contribute to the growing body of literature by tracing the inception, making and reception of Zvezdi (Bulgarian title), or Sterne (German title), a Bulgarian-East German co-production directed by Konrad Wolf. The film, which was awarded the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Festival in 1959, tells the story of an impossible love between a German Unteroffizier and a Greek Jewish woman who was detained with other Jews from Bulgarian-occupied Western Thrace in a Bulgarian transit camp, pending deportation to Poland. -

'Rescued in Vain'

Stars_PDF_Rescued in Vain_Layout 1 18.02.11 17:44 Seite 1 ‘Rescued in Vain’ Parapraxis and Deferred Action in Konrad Wolf’s Stars By Thomas Elsaesser y This essay is a chapter in Thomas Elsaesser's forthcoming book , Terror and TraUma: The Violence r a r b i of the Past in Germany's Present, and is pUblished here with the kind permission of the University of L m l i Minnesota Press. F A F E D e Konrad Wolf’s Sterne (Zvezdy / Stars , 1959) is one of the better known (thoUgh less often seen) films pro - h t y b dUced in the former GDR. As an early treatment of the reaction of an “ordinary” German to the concentration e s a e camps and the deportation of Jews, the film reflects the “clean conscience” of the state-owned DEFA film l e R stUdios in the process of coming to terms with the Nazi past ( VergangenheitsbewältigUng ). BUt Wolf’s film is D V D also aboUt love, self-sacrifice and resistance, and Uses filmic idioms reminiscent of classic melodrama and A • Italian neorealism, as well as the first stirrings of EUropean aUteUr cinema. Despite the almost sacrosanct s r a t S aUra sUrroUnding this film, we shoUld not hesitate to re-examine it, however, treating certain jUnctUres in its • s r plot strUctUre as a sort of palimpsest – that is, as a specific layering of moments, a sedimentation of known a t S s ’ images and historical references, whose political and hermeneUtic fUnction, I argUe, can be read anew in f l o retrospect. -

Film Aesthetics and the Politics of Identity in Divided Heaven and Solo Sunny

Spectral cinema from a phantom state: film aesthetics and the politics of identity in Divided Heaven and Solo Sunny Article (Accepted Version) Austin, Thomas (2016) Spectral cinema from a phantom state: film aesthetics and the politics of identity in Divided Heaven and Solo Sunny. Studies in Eastern European Cinema, 7 (3). pp. 274- 286. ISSN 2040-350X This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/61760/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Spectral cinema from a phantom state: film aesthetics and the politics of identity in Divided Heaven and Solo Sunny Thomas Austin * * [email protected] School of Media, Film and Music, University of Sussex, Brighton, BN1 9RQ, UK In this essay I draw on close textual analysis to consider the interface between film aesthetics and the politics of identity in Konrad Wolf’s Der geteilte Himmel / Divided Heaven (1964) and Solo Sunny (1979).