Isandhlwana and the Passing of a Proconsul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Colonial Office Group of the Public Record Office, London with Particular Reference to Atlantic Canada

THE COLONIAL OFFICE GROUP OF THE PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE, LONDON WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO ATLANTIC CANADA PETER JOHN BOWER PUBLIC ARCHIVES OF CANADA rn~ILL= - importance of the Coioniai office1 records housed in the Public Record Office, London, to an under- standing of the Canadian experience has long been recog- nized by our archivists and scholars. In the past one hundred years, the Public Archives of Canada has acquired contemporary manuscript duplicates of documents no longer wanted or needed at Chancery Lane, but more importantly has utilized probably every copying technique known to improve its collection. Painfully slow and tedious hand- transcription was the dominant technique until roughly the time of the Second World War, supplemented periodi- cally by typescript and various photoduplication methods. The introduction of microfilming, which Dominion Archivist W. Kaye Lamb viewed as ushering in a new era of service to Canadian scholars2, and the installation of a P.A.C. directed camera crew in the P.R.O. initiated a duplica- tion programme which in the next decade and a half dwarfed the entire production of copies prepared in the preceding seventy years. It is probably true that no other former British possession or colony has undertaken so concerted an effort to collect copies of these records which touch upon almost every aspect of colonial history. While the significance of the British records for . 1 For the sake of convenience, the term "Colonial Office'' will be used rather loosely from time to time to include which might more properly be described as precur- sors of the department. -

Colonial Administration Records (Migrated Archives): Basutoland (Lesotho) FCO 141/293 to 141/1021

Colonial administration records (migrated archives): Basutoland (Lesotho) FCO 141/293 to 141/1021 Most of these files date from the late 1940s participation of Basotho soldiers in the Second Constitutional development and politics to the early 1960s, as the British government World War. There is included a large group of considered the future constitution of Basutoland, files concerning the medicine murders/liretlo FCO 141/294-295: Constitutional reform in although there is also some earlier material. Many which occurred in Basutoland during the late Basutoland (1953-59) – of them concern constitutional developments 1940s and 1950s, and their relation to political concerns the development of during the 1950s, including the establishment and administrative change. For research already representative government of a legislative assembly in the late 1950s and undertaken on this area see: Colin Murray and through the establishment of a the legislative election in 1960. Many of the files Peter Sanders, Medicine Murder in Colonial Lesotho legislative assembly. concern constitutional development. There is (Edinburgh UP 2005). also substantial material on the Chief designate FCO 141/318: Basutoland Constitutional Constantine Bereng Seeiso and the role of the http://www.history.ukzn.ac.za/files/sempapers/ Commission; attitude of Basutoland British authorities in his education and their Murray2004.pdf Congress Party (1962); concerns promotion of him as Chief designate. relations with South Africa. The Resident Commisioners of Basutoland from At the same time, the British government 1945 to 1966 were: Charles Arden-Clarke (1942-46), FCO 141/320: Constitutional Review Commission considered the incorporation of Basutoland into Aubrey Thompson (1947-51), Edwin Arrowsmith (1961-1962); discussion of form South Africa, a position which became increasingly (1951-55), Alan Chaplin (1955-61) and Alexander of constitution leading up to less tenable as the Nationalist Party consolidated Giles (1961-66). -

Migrated Archives): Bahamas

Colonial administration records (migrated archives): Bahamas The Bahamas is a nation consisting of more than Land ownership 3,000 islands. Following a period of sporadic occupation by Spain, English settlements were FCO 141/13101: copies of leases and maps concerning the transfer of coastal land plots and established in the mid seventeenth century on the adjacent sea bed in an area known as the ‘tongue of the ocean’ for an the islands of Eleuthera and New Providence and undersea test evaluation centre and oceanographic research station, land the Bahamas became a Crown colony in 1717. at San Salvador for a US Naval facility and land at New Providence (eastern In 1776 the Bahamas surrendered to American district) for War Office purposes, 1962-1973 forces and were captured by Spain in 1782 but they were recaptured by British forces in 1783 and were officially restored to Great Britain International later that year under the Treaty of Versailles. In 1973 the Bahamas became an independent state FCO 141/13102: Commonwealth Foundation: this file consists of a letter from the foundation within the Commonwealth. concerning joining fees upon independence, papers concerning the visit to Nassau of Mr Chadwick, director of the Commonwealth Foundation, and The third tranche of records relating to the an itinerary of his grand tour of the Pacific which took in Fiji, Tonga, New administration of the Bahamas covers the Hebrides, New Zealand, Australia, Papua New Guinea, Singapore, Sarawak, years 1962 – 1973 and concern preparations Brunei, Sabah, Kuala Lumpur, India and Mauritius, 1972-1973 for independence. The records are arranged below within subject areas based on the non- FCO 141/13104: Haiti, British diplomatic representation: despatches regarding the possibility standard registration system used within the of the Government of the Bahamas paying the balance of the salary of Mr le Commissioner’s and Governor’s private office. -

Sir Bartle Frere and the Zulu War

Sir Bartle Frere and the Zulu War. By D.P. O’Connor _____________________________________________________________________________________________ That the border violations of 1878 were an inadequate reason for Britain to invade Zululand in 1879 has long been recognised. The consensus has it that Sir Bartle Frere, an imperial administrator of great experience, had been sent out to South Africa as Governor to carry through a confederation of all the various political units of South Africa at the behest of the Colonial Secretary, Lord Carnarvon, in order to affect a settlement that would provide security, from both internal and external threats, for the Cape settlers, economic development and a closer relationship with Britain. It would also reduce costs for the government in London and provide both Carnarvon and Frere with suitable climaxes to their careers. The policy was always an ambitious one and was already in doubt by the time Frere reached Cape Town. When Carnarvon resigned over Disraeli’s policy in the Balkan crisis of 1878, it seemed that Confederation had lost its main driving force, reducing its chances of success still further. This did not prevent Frere from continuing with the policy and, accustomed to a wide degree of discretion being granted to him, attempting to settle the recurrent instability of the region on his own initiative. After the annexation of the Transvaal in 1877, he became convinced that the destruction of the Zulu army was an ‘urgent necessity’ if the process of Confederation was to continue because Confederation would necessarily involve the settler polities paying for their own defence in the eventuality of a war with the Zulus and this they were most reluctant to do. -

Creation and Collapse: the British Indian Empire in Mesopotamia Before and After World War I

Creation and Collapse: The British Indian Empire in Mesopotamia Before and After World War I Austin McCleery Department of History Honors Thesis University of Colorado Boulder Defense: April 2nd, 2018 Committee: Primary Advisor: Susan Kingsley Kent, Department of History Outside Advisor: Nancy Billica, Department of Political Science Honors Representative: Matthew Gerber, Department of History 1 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I am deeply indebted to Professor Kent for her expertise, guidance, and willingness to work with my schedule. Her support and immense knowledge made this paper far less daunting and ultimately far more successful. I would also like to extend my deepest gratitude to Professor Gerber for leading me through the thesis process and helping me switch topics when my initial choice fell through. To Professor Billica, thank you for encouraging my interests beyond this topic and offering invaluable career advice and much appreciated edits. Finally, to all my friends and family who listened to me talk about this thesis for almost two years, your patience and support played a huge role in getting me to the end. To those who spent innumerable hours in the library with me, I greatly appreciated the company. 2 Abstract This paper explores British India and the Government of India’s involvement in Mesopotamia [modern-day Iraq] before, during, and after World War I. By bringing these regions together, this study challenges prior assumptions that India and the Middle East exist in entirely distinct historic spheres. Instead I show that the two regions share close, interrelated histories that link both the British Empire and the changing colonial standards. -

Kingship in the Age of Extraction: the Reshaping of Nigerian Identity And

1 Kingship in the Age of Extraction: How British Deconstruction and Isolation of African Kingship Reshaped Identity and Spurred Nigeria’s North/South Divide, 1885-1937 By: Hurst Williamson Honors Thesis Rice University Fall 2014-Spring 2015 2 This thesis is dedicated to all of those whose tireless efforts and support made this work possible: my loving mother, my selfless father, my wonderful advisor Dr. Jared Staller, and our miraculous program director Dr. Lisa Balabanlilar. Thank you all for your encouragement and assistance, this thesis is for you. 3 Table of Contents: Map of Nigeria’s Linguistic Groups…………………………………………….3 Map of Southern Nigeria’s Three Colonial Entities…………………………...4 Introduction………………………………………………………………………5 The South: Declining Kings, Direct Rule……………………………………...12 The North: The Costs of Neglect, Indirect Rule……………………………....28 The Amalgamation: One Nigeria, Two Identities…………………………….42 The Church, the Mosque, the University, and the Army…………………….58 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………77 Work Cited……………………………………………………………………...80 4 5 Nigeria’s Linguistic Groups by Most-Populated Region 1 1 This map is a general representation of Nigeria’s major linguistic groups based on region. Nigeria has hundreds of people groups, so this map is representative of only the major population pockets of the largest groups; Central Intelligence Agency, “Map of linguistic groups in Nigeria,” (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1979. 6 Map of Southern Nigeria’s Three Colonial Entities 2 2 This map shows the three colonial entities (Lagos Colony, Royal Niger Company, Oil Rivers Protectorate) in southern Nigeria after the creation of the Southern Nigerian Protectorate in 1900; Dead Country Banknotes and Stamps, “Niger Coast Protectorate, 1893-1900,” (WordPress, 2012). -

'The Evils of Locust Bait': Popular Nationalism During the 1945 Anti-Locust Control Rebellion in Colonial Somaliland

‘THE EVILS OF LOCUST BAIT’: POPULAR NATIONALISM DURING THE 1945 ANTI-LOCUST CONTROL REBELLION IN COLONIAL SOMALILAND I Since the 1960s, students of working-class politics, women’s his- tory, slave resistance, peasant revolts and subaltern nationalism have produced a rich and global historiography on the politics of popular classes. Except for two case studies, popular politics have so far been ignored in Somali studies, yet anti-colonial nationalism was predominantly popular from the beginning of colonial rule in 1884, when Great Britain conquered the northern Somali coun- try, the Somaliland Protectorate (see Map).1 The British justified colonial conquest as an educational enterprise because the Somalis, as Major F. M. Hunt stated, were ‘wild’, ‘violent’, ‘uncivilised’, without any institutions or government; hence the occupation of the country was necessary to begin the task of ‘educating the Somal in self-government’.2 The Somalis never accepted Britain’s self-proclaimed mission. From 1900 to 1920, Sayyid Muhammad Abdulla Hassan organized a popular rural- based anti-colonial movement.3 From 1920 to 1939, various anti- colonial resistance acts were carried out in both the rural and urban areas, such as the 1922 tax revolt in Hargeysa and Burao, 1 This article is based mainly on original colonial sources and Somali poetry. The key documents are district weekly reports sent to the secretary to the government, and then submitted to the Colonial Office. These are the ‘Anti-Locust Campaign’ reports, and I include the reference numbers and the dates. I also use administrative reports, and yearly Colonial Office reports. All original sources are from the Public Record Office, London, and Rhodes House Library, Oxford, England. -

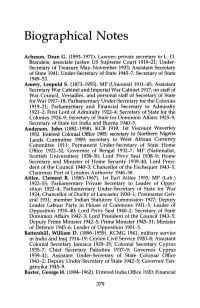

Biographical Notes

Biographical Notes Acheson, Dean G. (1893-1971). Lawyer; private secretary to L. D. Brandeis; associate justice US Supreme Court 1919-21; Und er Secretary of Treasury May-November 1933; Assistant Secretary of State 1941; Under-Secretary of State 1945-7; Secretary of State 1949-53. Amery, Leopold S. (1873-1955). MP (Unionist) 1911-45; Assistant Secretary War Cabinet and Imperial War Cabinet 1917; on staff of War Council, Versailles, and personal staff of Secretary of State for War 1917-18; Parliamentary Under-Secretary for the Colonies 1919-21; Parliamentary and Financial Secretary to Admiralty 1921-2; First Lord of Admiralty 1922-4; Secretary of State for the Colonies 1924-9; Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs 1925-9; Secretary of State for India and Burma 1940-5. Anderson, John (1882-1958). KCB 1919, 1st Viscount Waverley 1952. Entered Colonial Office 1905; secretary to Northem Nigeria Lands Committee 1909; secretary to West African Currency Committee 1911; Permanent Under-Secretary of State Horne Office 1922-32; Governor of Bengal 1932-7; MP (Nationalist, Scottish Universities) 1938-50; Lord Privy Seal 1938-9; Horne Secretary and Minister of Horne Security 1939-40; Lord Presi dent of the Counci11940-3; Chancellor of the Exchequer 1943-5; Chairman Port of London Authority 1946-58. Attlee, Clement R. (1883-1967). 1st Earl Attlee 1955; MP (Lab.) 1922-55; Parliamentary Private Secretary to Leader of Oppo sition 1922-4; Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for War 1924; Chancellor of Duchy of Lancaster 1930-1; Postmaster Gen eral 1931; member Indian Statutory Commission 1927; Deputy Leader Labour Party in House of Commons 1931-5; Leader öf Opposition 1935-40; Lord Privy Seal 1940-2; Secretary of State Dominion Affairs 1942-3; Lord President of the CounciI1943-5; Deputy Prime Minister 1942-5; Prime Minister 1945-51; Minister of Defence 1945-6; Leader of Opposition 1951-5. -

The British Occupation of Southern Nigeria, Thesis

374 Nei Ufa, ss THE BRITISH OCCUPATION OF SOUTHERN NIGERIA, 1851-1906 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Coundil of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Andrew 0. Igbineweka, B. A. Denton, Texas December, 1979 Igbineweka, Andrew 0., The British Occupation of Southern Nigeria, 1851-1906. Master of Arts (History), December, 1979, 72 pp., bibliography, 47 titles. The study indicates that the motives which impelled the creation of the Protectorate of Southern Nigeria were complex, variable, and sometimes contradictory. Many Englishmen within and without the government, indeed, ad- vocated the occupation of the area to suppress the slave trade, but this humanitarian ambition, on balance, was not as significant as political and economic interests. The importance of the Niger waterway, rivalry with France and other maritime nations, andmissionary work, all led Britain to adopt a policy of aggrandizement and to proclaim a pro- tectorate over the Niger districts, thereby laying the foundation for modern Nigeria. The London government ac- quired territory through negotiating treaties with the native chiefs, conquest, and purchase. British policy and consular rule between 1851 and 1906 was characterized by gunboat diplomacy, brutality, and flagrant disregard for treaty rights; nonetheless, the British presence has made a positive impact on Nigeria's historical, political, economic, intellectual, and cultural development. PRE FACE An investigation of the British occupation of Southern Nigeria reveals that recent historians -have neglected the genesis of this colonial enterprise and have emphasized the rise of Nigerian nationalism and federalism in the twentieth century. -

Herman Merivale and Colonial Office Indian Policy in the Mid-Nineteenth Century

HERMAN MERIVALE AND COLONIAL OFFICE INDIAN POLICY IN THE MID-NINETEENTH CENTURY DAVID T. MCNAB, Office of Indian Resource Policy, Ministry of Natural Resources, Whitney Block, Queen's Park, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M7A 1W3 ABSTRACT/RESUME This paper outlines the gradual movement of Indian policy from Britain, where Merivale was Instrumental in its development, to the various separate colonies of British North America. By the time Canada was formed in 1867, there existed a series of regional Indian policies, rather than a comprehensive, "sea-to-sea" policy. Cette étude décrit le déplacement graduel, de la Grande-Bretagne (où Merivale exerça une influence prépondérante sur son développement) vers les diverses colonies de l'Amérique du Nord britannique, du siège de la politique relative aux indigènes. A l'époque de la formation de l'union canadienne en 1887, le véritable éventail de politique régionales distinctes, qui darts ce domaine était déjà en place, tenait lieu d'une seule et unique politique pour tout le pays. 278 DAVID T. MCNAB Historians have examined the origins of Canadian Indian policy and have generally agreed that prior to Confederation, it was a product of the ideas and actions of politicians and administrators in the Canadas. ² This interpretation is partially true, but it has tended to obscure two important facts. In the first instance, before 1860, the Colonial Office in London, England and the colonial governors rather than the Indian Department were responsible for Indian (i.e. Indian and Metis) policy in British North America. The Indian Department dealt with administrative details while the British Government still held within its purview questions of policy. -

Framing Britain's Official Mind, 1854-1934 Blake Allen Duffield University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 The Grey Men of Empire: Framing Britain's Official Mind, 1854-1934 Blake Allen Duffield University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Recommended Citation Duffield, Blake Allen, "The Grey Men of Empire: Framing Britain's Official Mind, 1854-1934" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1447. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1447 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. “The Grey Men of Empire: Framing Britain’s Official Mind, 1854-1934" A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Blake Duffield Ouachita Baptist University Bachelor of Arts in History, 2008 University of Arkansas Master of Arts in History, 2010 May 2016 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. __________________________________ Dr. Benjamin Grob-Fitzgibbon Dissertation Chair ___________________________________ __________________________________ Dr. Joel Gordon Dr. Randall Woods Committee Member Committee Member Abstract “The Grey Men of Empire: Framing Britain’s Official Mind, 1854-1934,” examines the crucial, yet too often-undervalued role of Britain’s imperial bureaucracy in forging the ethos and identity behind the policy-decisions made across the Empire. Although historians have tended to dismiss them as the faceless and voiceless grey men of Empire, this study argues that the political officers of the Colonial Services represented the backbone of British colonial administration and, quite literally, were responsible for its survival and proliferation. -

Sir Bartle Frere: Colonial Administrator of the Victorian Period

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 12-1-1972 Sir Bartle Frere: Colonial administrator of the Victorian period Anthony C. Brewer University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Brewer, Anthony C., "Sir Bartle Frere: Colonial administrator of the Victorian period" (1972). Student Work. 390. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/390 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SIR BARTLE FRERE: COLONIAL ADMINISTRATOR OF THE VICTORIAN PERIOD A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska at Omaha In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts fcy ■ Anthony C., Brewer December 1972 UMI Number: EP73028 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. D lsseitsiion PSfc/blishiog UMI EP73028 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest' ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Accepted for the faculty of The Graduate College of the University of Nebraska at Omaha, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts.