Kingship in the Age of Extraction: the Reshaping of Nigerian Identity And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mis-Education of the African Child: the Evolution of British Colonial Education Policy in Southern Nigeria, 1900–1925

Athens Journal of History - Volume 7, Issue 2, April 2021 – Pages 141-162 The Mis-education of the African Child: The Evolution of British Colonial Education Policy in Southern Nigeria, 1900–1925 By Bekeh Utietiang Ukelina Education did not occupy a primal place in the European colonial project in Africa. The ideology of "civilizing mission", which provided the moral and legal basis for colonial expansion, did little to provide African children with the kind of education that their counterparts in Europe received. Throughout Africa, south of the Sahara, colonial governments made little or no investments in the education of African children. In an attempt to run empire on a shoestring budget, the colonial state in Nigeria provided paltry sums of grants to the missionary groups that operated in the colony and protectorate. This paper explores the evolution of the colonial education system in the Southern provinces of Nigeria, beginning from the year of Britain’s official colonization of Nigeria to 1925 when Britain released an official policy on education in tropical Africa. This paper argues that the colonial state used the school system as a means to exert power over the people. Power was exercised through an education system that limited the political, technological, and economic advancement of the colonial people. The state adopted a curricular that emphasized character formation and vocational training and neglected teaching the students, critical thinking and advanced sciences. The purpose of education was to make loyal and submissive subjects of the state who would serve as a cog in the wheels of the exploitative colonial machine. -

Festival Events 1

H.E. Lieutenant-General Olusegun Obasanjo, Head of State of Nigeria and Festival Patron. (vi) to facilitate a periodic 'return to origin' in Africa by Black artists, writers and performers uprooted to other continents. VENUE OFEVENTS The main venue is Lagos, capital of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. But one major attraction, the Durbar. will take place in Kaduna, in the northern part basic facts of the country. REGISTRATION FEES Preparations are being intensified for the Second World There is a registration fee of U.S. $10,000 per partici- Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture to be held pating country or community. in Nigeria from 15th January to 12th February, 1977. The First Festival was held in Dakar, Senegal, in 1966. GOVERNING BODY It was then known simply as the World Festival of Negro The governing body for the Festival is the International Arts. Festival Committee representing the present 16 Festival At the end of that First Festival in 1966, Nigeria was Zones into which the Black African world has been invited to host the Second Festival in 1970. Nigeria divided. These 16 Zones are: South America, the accepted the invitation, but because of the internal Caribbean countries, USA/Canada, United Kingdom and situation in the country, it was not possible to hold the Ireland, Europe, Australia/Asia, Eastern Africa, Southern Festival that year. Africa, East Africa (Community), Central Africa I and II, At the end of the Nigerian civil war, the matter was WestAfrica (Anglophone), West Africa (Francophone) I resuscitated, and the Festival was rescheduled to be held and II, North Africa and the Liberation Movements at the end of 1975. -

Taxes, Institutions, and Governance: Evidence from Colonial Nigeria

Taxes, Institutions and Local Governance: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Colonial Nigeria Daniel Berger September 7, 2009 Abstract Can local colonial institutions continue to affect people's lives nearly 50 years after decolo- nization? Can meaningful differences in local institutions persist within a single set of national incentives? The literature on colonial legacies has largely focused on cross country comparisons between former French and British colonies, large-n cross sectional analysis using instrumental variables, or on case studies. I focus on the within-country governance effects of local insti- tutions to avoid the problems of endogeneity, missing variables, and unobserved heterogeneity common in the institutions literature. I show that different colonial tax institutions within Nigeria implemented by the British for reasons exogenous to local conditions led to different present day quality of governance. People living in areas where the colonial tax system required more bureaucratic capacity are much happier with their government, and receive more compe- tent government services, than people living in nearby areas where colonialism did not build bureaucratic capacity. Author's Note: I would like to thank David Laitin, Adam Przeworski, Shanker Satyanath and David Stasavage for their invaluable advice, as well as all the participants in the NYU predissertation seminar. All errors, of course, remain my own. Do local institutions matter? Can diverse local institutions persist within a single country or will they be driven to convergence? Do decisions about local government structure made by colonial governments a century ago matter today? This paper addresses these issues by looking at local institutions and local public goods provision in Nigeria. -

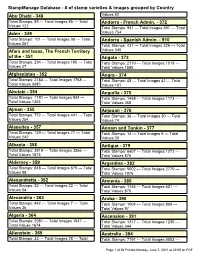

Stampmanage Database

StampManage Database - # of stamp varieties & images grouped by Country Abu Dhabi - 348 Values 82 Total Stamps: 89 --- Total Images 85 --- Total Andorra - French Admin. - 372 Values 122 Total Stamps: 941 --- Total Images 587 --- Total Aden - 349 Values 754 Total Stamps: 101 --- Total Images 98 --- Total Andorra - Spanish Admin. - 910 Values 267 Total Stamps: 437 --- Total Images 326 --- Total Afars and Issas, The French Territory Values 340 of the - 351 Angola - 373 Total Stamps: 294 --- Total Images 180 --- Total Total Stamps: 2170 --- Total Images 1019 --- Values 27 Total Values 1580 Afghanistan - 352 Angra - 374 Total Stamps: 2184 --- Total Images 1768 --- Total Stamps: 48 --- Total Images 42 --- Total Total Values 3485 Values 101 Aitutaki - 354 Anguilla - 375 Total Stamps: 1191 --- Total Images 934 --- Total Stamps: 1468 --- Total Images 1173 --- Total Values 1303 Total Values 365 Ajman - 355 Anjouan - 376 Total Stamps: 772 --- Total Images 441 --- Total Total Stamps: 36 --- Total Images 30 --- Total Values 254 Values 74 Alaouites - 357 Annam and Tonkin - 377 Total Stamps: 139 --- Total Images 77 --- Total Total Stamps: 14 --- Total Images 6 --- Total Values 242 Values 28 Albania - 358 Antigua - 379 Total Stamps: 3919 --- Total Images 3266 --- Total Stamps: 6607 --- Total Images 1273 --- Total Values 1873 Total Values 876 Alderney - 359 Argentina - 382 Total Stamps: 848 --- Total Images 675 --- Total Total Stamps: 5002 --- Total Images 2770 --- Values 88 Total Values 7076 Alexandretta - 362 Armenia - 385 Total Stamps: 32 --- Total -

Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean

BLACK INTERNATIONALISM AND AFRICAN AND CARIBBEAN INTELLECTUALS IN LONDON, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Professor Bonnie G. Smith And approved by _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2008 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean Intellectuals in London, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA Dissertation Director: Bonnie G. Smith During the three decades between the end of World War I and 1950, African and West Indian scholars, professionals, university students, artists, and political activists in London forged new conceptions of community, reshaped public debates about the nature and goals of British colonialism, and prepared the way for a revolutionary and self-consciously modern African culture. Black intellectuals formed organizations that became homes away from home and centers of cultural mixture and intellectual debate, and launched publications that served as new means of voicing social commentary and political dissent. These black associations developed within an atmosphere characterized by a variety of internationalisms, including pan-ethnic movements, feminism, communism, and the socialist internationalism ascendant within the British Left after World War I. The intellectual and political context of London and the types of sociability that these groups fostered gave rise to a range of black internationalist activity and new regional imaginaries in the form of a West Indian Federation and a United West Africa that shaped the goals of anticolonialism before 1950. -

Colonialism and Economic Development in Africa

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES COLONIALISM AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA Leander Heldring James A. Robinson Working Paper 18566 http://www.nber.org/papers/w18566 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 November 2012 We are grateful to Jan Vansina for his suggestions and advice. We have also benefitted greatly from many discussions with Daron Acemoglu, Robert Bates, Philip Osafo-Kwaako, Jon Weigel and Neil Parsons on the topic of this research. Finally, we thank Johannes Fedderke, Ewout Frankema and Pim de Zwart for generously providing us with their data. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2012 by Leander Heldring and James A. Robinson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Colonialism and Economic Development in Africa Leander Heldring and James A. Robinson NBER Working Paper No. 18566 November 2012 JEL No. N37,N47,O55 ABSTRACT In this paper we evaluate the impact of colonialism on development in Sub-Saharan Africa. In the world context, colonialism had very heterogeneous effects, operating through many mechanisms, sometimes encouraging development sometimes retarding it. In the African case, however, this heterogeneity is muted, making an assessment of the average effect more interesting. -

The Colonial Office Group of the Public Record Office, London with Particular Reference to Atlantic Canada

THE COLONIAL OFFICE GROUP OF THE PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE, LONDON WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO ATLANTIC CANADA PETER JOHN BOWER PUBLIC ARCHIVES OF CANADA rn~ILL= - importance of the Coioniai office1 records housed in the Public Record Office, London, to an under- standing of the Canadian experience has long been recog- nized by our archivists and scholars. In the past one hundred years, the Public Archives of Canada has acquired contemporary manuscript duplicates of documents no longer wanted or needed at Chancery Lane, but more importantly has utilized probably every copying technique known to improve its collection. Painfully slow and tedious hand- transcription was the dominant technique until roughly the time of the Second World War, supplemented periodi- cally by typescript and various photoduplication methods. The introduction of microfilming, which Dominion Archivist W. Kaye Lamb viewed as ushering in a new era of service to Canadian scholars2, and the installation of a P.A.C. directed camera crew in the P.R.O. initiated a duplica- tion programme which in the next decade and a half dwarfed the entire production of copies prepared in the preceding seventy years. It is probably true that no other former British possession or colony has undertaken so concerted an effort to collect copies of these records which touch upon almost every aspect of colonial history. While the significance of the British records for . 1 For the sake of convenience, the term "Colonial Office'' will be used rather loosely from time to time to include which might more properly be described as precur- sors of the department. -

Revisiting the Budgetary Deficit Factor in the 1914 Amalgamation of Northern and Southern Protectorates: a Case Study of Zaria Province, 1903-1914

International Journal of Liberal Arts and Social Science Vol. 5 No. 9 December 2017 Revisiting the Budgetary Deficit Factor in the 1914 Amalgamation of Northern and Southern Protectorates: A Case Study of Zaria Province, 1903-1914 Dr Attahiru Ahmad SIFAWA Department of History, Faculty of Arts and social sciences, Sokoto State University Sokoto, Nigeria Email: [email protected] Dr SIRAJO Muhammad Sokoto Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies Sokoto State University, Sokoto, Nigeria Murtala MARAFA Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Sokoto State University, Sokoto, Nigeria Email: [email protected] Corresponding Author: Dr Attahiru Ahmad SIFAWA Sponsored by: Tertiary Education Trust Fund, Nigeria 1 International Journal of Liberal Arts and Social Science ISSN: 2307-924X www.ijlass.org Abstract One of the widely propagated notion on the British Administration of Northern Nigeria, and in particular, the 1914 Amalgamation of Northern and Southern protectorates was that the absence of seaboard and custom duties therefrom, and other sources of revenue, made the protectorate of Northern Nigeria depended mostly on direct taxation as its sources of revenue. The result was the inadequacy of the locally generated revenue to meet even the half of the region’s financial expenditure for over 10 years. Consequently, the huge budgetary deficit from the North had to be met with grant – in-aid which averaged about a quarter of a million sterling pounds from the British tax payers’ money annually. Northern Nigeria was thus amalgamated with Southern Nigeria in order to benefit from the latter’s huge budgetary surpluses and do away with imperial grant –in- aid from Britain. -

Republic of Sierra Leone

Grids & Datums REPUBLIC OF SIE rr A LEONE by Clifford J. Mugnier, C.P., C.M.S. “European contacts with Sierra Leone were among the first in West ary between the territories of Sierra Leone and Guinea from the Atlantic Africa. In 1652, the first slaves in North America were brought from Ocean inland along the drainage divide of the Great Scarcies and Sierra Leone to the Sea Islands off the coast of the southern United Melikhoure to an indefinite point in the interior. On August 10, 1889, States. During the 1700s there was a thriving trade bringing slaves France and the United Kingdom signed an arrangement extending from Sierra Leone to the plantations of South Carolina and Georgia the Guinea–Sierra Leone boundary northward to the 10th parallel and where their rice-farming skills made them particularly valuable. In then eastward to the 13th meridian west of Paris (10° 39’ 46.05” West 1787 the British helped 400 freed slaves from the United States, of Greenwich). In order to determine the boundary between British Nova Scotia, and Great Britain return to Sierra Leone to settle in what and French spheres of influence west and south of the upper Niger they called the ‘Province of Freedom.’ Disease and hostility from the river, an Anglo-French agreement of June 26, 1891, stated that the indigenous people nearly eliminated the first group of returnees. 13th meridian west of Paris was to be followed where possible from This settlement was joined by other groups of freed slaves and soon the 10th parallel to Timbekundu (the source of the Timbe or Niger). -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

Colonial Administration Records (Migrated Archives): Basutoland (Lesotho) FCO 141/293 to 141/1021

Colonial administration records (migrated archives): Basutoland (Lesotho) FCO 141/293 to 141/1021 Most of these files date from the late 1940s participation of Basotho soldiers in the Second Constitutional development and politics to the early 1960s, as the British government World War. There is included a large group of considered the future constitution of Basutoland, files concerning the medicine murders/liretlo FCO 141/294-295: Constitutional reform in although there is also some earlier material. Many which occurred in Basutoland during the late Basutoland (1953-59) – of them concern constitutional developments 1940s and 1950s, and their relation to political concerns the development of during the 1950s, including the establishment and administrative change. For research already representative government of a legislative assembly in the late 1950s and undertaken on this area see: Colin Murray and through the establishment of a the legislative election in 1960. Many of the files Peter Sanders, Medicine Murder in Colonial Lesotho legislative assembly. concern constitutional development. There is (Edinburgh UP 2005). also substantial material on the Chief designate FCO 141/318: Basutoland Constitutional Constantine Bereng Seeiso and the role of the http://www.history.ukzn.ac.za/files/sempapers/ Commission; attitude of Basutoland British authorities in his education and their Murray2004.pdf Congress Party (1962); concerns promotion of him as Chief designate. relations with South Africa. The Resident Commisioners of Basutoland from At the same time, the British government 1945 to 1966 were: Charles Arden-Clarke (1942-46), FCO 141/320: Constitutional Review Commission considered the incorporation of Basutoland into Aubrey Thompson (1947-51), Edwin Arrowsmith (1961-1962); discussion of form South Africa, a position which became increasingly (1951-55), Alan Chaplin (1955-61) and Alexander of constitution leading up to less tenable as the Nationalist Party consolidated Giles (1961-66). -

World Bank Document

RESTRICTED R Report NO. EA-79 Public Disclosure Authorized This report was prepared for use within the Bank. In making it available to others, the Bank assumes no responsibility to them for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein. INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT Public Disclosure Authorized THE ECONOMY OF NIGERIA Public Disclosure Authorized April 18, 1958 Public Disclosure Authorized Department of Operations - Europe, Africa and Australasia CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Unit: West African i I West African i - L 1 Sterling - U.S. $2.80 In this report the f sign, when not otherwise identified, means the West African pound. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page BASIC STATISTICS MAPS CHARTS................................................8, 22, 23, 25, 31, 32 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS....................................... 1 I. GENERAL BACKGROUND....................................... 3 Natural Setting.......................................... 3 Population.............................................. 3 Political Setting......................................... 5 II. STRUCTURE OF THE ECONOMY................................... 7 Economic Growth............................................ 7 National Accounts......................................... 8 Economic Organization.................. ........... ....... 9 III. DEVELOPMENT OF MAJOR SECTORS............................... 12 Agriculture............................... ............... 12 Mining.................................................. 16 Industry..................