Interrogating British Residential Segregation in Nigeria, 1899-1919

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mis-Education of the African Child: the Evolution of British Colonial Education Policy in Southern Nigeria, 1900–1925

Athens Journal of History - Volume 7, Issue 2, April 2021 – Pages 141-162 The Mis-education of the African Child: The Evolution of British Colonial Education Policy in Southern Nigeria, 1900–1925 By Bekeh Utietiang Ukelina Education did not occupy a primal place in the European colonial project in Africa. The ideology of "civilizing mission", which provided the moral and legal basis for colonial expansion, did little to provide African children with the kind of education that their counterparts in Europe received. Throughout Africa, south of the Sahara, colonial governments made little or no investments in the education of African children. In an attempt to run empire on a shoestring budget, the colonial state in Nigeria provided paltry sums of grants to the missionary groups that operated in the colony and protectorate. This paper explores the evolution of the colonial education system in the Southern provinces of Nigeria, beginning from the year of Britain’s official colonization of Nigeria to 1925 when Britain released an official policy on education in tropical Africa. This paper argues that the colonial state used the school system as a means to exert power over the people. Power was exercised through an education system that limited the political, technological, and economic advancement of the colonial people. The state adopted a curricular that emphasized character formation and vocational training and neglected teaching the students, critical thinking and advanced sciences. The purpose of education was to make loyal and submissive subjects of the state who would serve as a cog in the wheels of the exploitative colonial machine. -

Urban Governance and Turning African Ciɵes Around: Lagos Case Study

Advancing research excellence for governance and public policy in Africa PASGR Working Paper 019 Urban Governance and Turning African CiƟes Around: Lagos Case Study Agunbiade, Elijah Muyiwa University of Lagos, Nigeria Olajide, Oluwafemi Ayodeji University of Lagos, Nigeria August, 2016 This report was produced in the context of a mul‐country study on the ‘Urban Governance and Turning African Cies Around ’, generously supported by the UK Department for Internaonal Development (DFID) through the Partnership for African Social and Governance Research (PASGR). The views herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those held by PASGR or DFID. Author contact informaƟon: Elijah Muyiwa Agunbiade University of Lagos, Nigeria [email protected] or [email protected] Suggested citaƟon: Agunbiade, E. M. and Olajide, O. A. (2016). Urban Governance and Turning African CiƟes Around: Lagos Case Study. Partnership for African Social and Governance Research Working Paper No. 019, Nairobi, Kenya. ©Partnership for African Social & Governance Research, 2016 Nairobi, Kenya [email protected] www.pasgr.org ISBN 978‐9966‐087‐15‐7 Table of Contents List of Figures ....................................................................................................................... ii List of Tables ........................................................................................................................ iii Acronyms ............................................................................................................................ -

Kareem Olawale Bestoyin*

Historia Actual Online, 46 (2), 2018: 43-57 ISSN: 1696-2060 OIL, POLITICS AND CONFLICTS IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF NIGERIA AND SOUTH SUDAN Kareem Olawale Bestoyin* *University of Lagos, Nigeria. E-mail: [email protected] Recibido: 3 septiembre 2017 /Revisado: 28 septiembre 2017 /Aceptado: 12 diciembre 2017 /Publicado: 15 junio 2018 Resumen: A lo largo de los años, el Áfica sub- experiencing endemic conflicts whose conse- sahariana se ha convertido en sinónimo de con- quences have been under development and flictos. De todas las causas conocidas de conflic- abject poverty. In both countries, oil and poli- tos en África, la obtención de abundantes re- tics seem to be the driving force of most of cursos parece ser el más prominente y letal. these conflicts. This paper uses secondary data Nigeria y Sudán del Sur son algunos de los mu- and qualitative methodology to appraise how chos países ricos en recursos en el África sub- the struggle for the hegemony of oil resources sahariana que han experimentado conflictos shapes and reshapes the trajectories of con- endémicos cuyas consecuencias han sido el flicts in both countries. Hence this paper de- subdesarrollo y la miserable pobreza. En ambos ploys structural functionalism as the framework países, el petróleo y las políticas parecen ser el of analysis. It infers that until the structures of hilo conductor de la mayoría de estos conflic- governance are strengthened enough to tackle tos. Este artículo utiliza metodología de análisis the developmental needs of the citizenry, nei- de datos secundarios y cualitativos para evaluar ther the amnesty programme adopted by the cómo la pugna por la hegemonía de los recur- Nigerian government nor peace agreements sos energéticos moldea las trayectorias de los adopted by the government of South Sudan can conflictos en ambos países. -

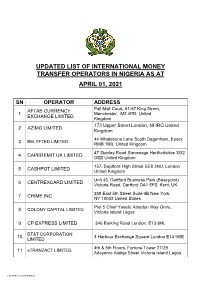

Updated List of International Money Transfer Operators in Nigeria As At

UPDATED LIST OF INTERNATIONAL MONEY TRANSFER OPERATORS IN NIGERIA AS AT APRIL 01, 2021 SN OPERATOR ADDRESS AFTAB CURRENCY Pall Mall Court, 61-67 King Street, 1 Manchester, M2 4PD, United EXCHANGE LIMITED Kingdom 173 Upper Street London, NI IRG United 2 AZIMO LIMITED Kingdom 44 Whalebone Lane South Dagenham, Essex 3 BELYFTED LIMITED RMB 1BB, United Kingdom 47 Stanley Road Stevenage Hertfordshire SG2 4 CAPEREMIT UK LIMITED OEE United Kingdom 157, Deptford High Street SE8 3NU, London 5 CASHPOT LIMITED United Kingdom Unit 46, Dartford Business Park (Basepoint) 6 CENTREXCARD LIMITED Victoria Road, Dartford DA1 5FS, Kent, UK 239 East 5th Street Suite 4B New York, 7 CHIME INC. NY 10003 United States Plot 5 Chief Yesefu Abiodun Way Oniru, 8 COLONY CAPITAL LIMITED Victoria Island Lagos 9 CP EXPRESS LIMITED 346 Barking Road London, E13 8HL DT&T CORPORATION 10 3 Harbour Exchange Square London E14 9GE LIMITED 4th & 5th Floors, Fortune Tower 27/29 11 eTRANZACT LIMITED Adeyemo Alakija Street Victoria Island Lagos Classified as Confidential FIEM GROUP LLC DBA 1327, Empire Central Drive St. 110-6 Dallas 12 PING EXPRESS Texas 6492 Landover Road Suite A1 Landover 13 FIRST APPLE INC. MD20785 Cheverly, USA FLUTTERWAVE 14 TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS 8 Providence Street, Lekki Phase 1 Lagos LIMITED FORTIFIED FRONTS LIMITED 15 in Partnership with e-2-e PAY #15 Glover Road Ikoyi, Lagos LIMITED FUNDS & ELECTRONIC 16 No. 15, Cameron Road, Ikoyi, Lagos TRANSFER SOLUTION FUNTECH GLOBAL Clarendon House 125 Shenley Road 17 COMMUNICATIONS Borehamwood Heartshire WD6 1AG United LIMITED Kingdom GLOBAL CURRENCY 1280 Ashton Old Road Manchester, M11 1JJ 18 TRAVEL & TOURS LIMITED United Kingdom Rue des Colonies 56, 6th Floor-B1000 Brussels 19 HOMESEND S.C.R.L Belgium IDT PAYMENT SERVICES 20 520 Broad Street USA INC. -

Anchoring the African Internet Ecosystem

Anchoring the African Internet Ecosystem Anchoring the African Internet Ecosystem: Lessons from Kenya and Nigeria’s Internet Exchange Point Growth By Michael Kende June 2020 CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 internetsociety.org 1 Anchoring the African Internet Ecosystem Table of contents 3 Executive summary 6 Background: A vision for Africa 8 Introduction: How to get there from here 13 Success stories: Kenya and Nigeria today 18 Results that stand the test of time 20 Change factors: Replicable steps toward measurable outcomes 27 Market gaps 29 Recommendations 33 Conclusions 34 Annex A: Kenya Internet Exchange Point 35 Annex B: Internet Exchange Point of Nigeria 36 Annex C: Acknowledgments 37 Annex D: Glossary of terms 38 Annex E: List of figures and tables CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 internetsociety.org 2 Anchoring the African Internet Ecosystem Executive summary In 2010, the Internet Society’s team in Africa set an The rapid pace of Internet ecosystem ambitious goal that 80% of African Internet traffic development in both Kenya and Nigeria since would be locally accessible by 2020. 2012 underscores the critical role that IXPs Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) are key to realizing and the accompanying infrastructure play in this goal in that they enable local traffic exchange and the establishment of strong and sustainable access to content. To document this role, in 2012, the Internet ecosystems. Internet Society commissioned a study to identify and quantify the significant benefits of two leading African This development produces significant day-to-day IXPs at the time: KIXP in Kenya and IXPN in Nigeria. value—the present COVID-19 crisis magnifies one such The Internet Society is pleased to publish this update benefit in the smooth accommodation of sudden of the original study. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Here Is a List of Assets Forfeited by Cecilia Ibru

HERE IS A LIST OF ASSETS FORFEITED BY CECILIA IBRU 1. Good Shepherd House, IPM Avenue , Opp Secretariat, Alausa, Ikeja, Lagos (registered in the name of Ogekpo Estate Managers) 2. Residential block with 19 apartments on 34, Bourdillon Road , Ikoyi (registered in the name of Dilivent International Limited). 3.20 Oyinkan Abayomi Street, Victoria Island (remainder of lease or tenancy upto 2017). 4. 57 Bourdillon Road , Ikoyi. 5. 5A George Street , Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited), 6. 5B George Street , Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 7. 4A Iru Close, Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 8. 4B Iru Close, Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 9. 16 Glover Road , Ikoyi (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 10. 35 Cooper Road , Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 11. Property situated at 3 Okotie-Eboh, SW Ikoyi. 12. 35B Isale Eko Avenue , Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi. 13. 38A Isale Eko Avenue , Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi (registered in the name of Meeky Enterprises Limited). 14. 38B Isale Eko Avenue , Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi (registered in the name of Aleksander Stankov). 15. Multiple storey multiple user block of flats under construction 1st Avenue , Banana Island , Ikoyi, Lagos , (with beneficial interest therein purchased from the developer Ibalex). 16. 226, Awolowo Road , Ikoyi, Lagos (registered in the name of Ogekpo Estate Managers). 17. 182, Awolowo Road , Ikoyi, Lagos , (registered in the name of Ogekpo Estate Managers). 18. 12-storey Tower on one hectare of land at Ozumba Mbadiwe Water Front, Victoria Island . -

Taxes, Institutions, and Governance: Evidence from Colonial Nigeria

Taxes, Institutions and Local Governance: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Colonial Nigeria Daniel Berger September 7, 2009 Abstract Can local colonial institutions continue to affect people's lives nearly 50 years after decolo- nization? Can meaningful differences in local institutions persist within a single set of national incentives? The literature on colonial legacies has largely focused on cross country comparisons between former French and British colonies, large-n cross sectional analysis using instrumental variables, or on case studies. I focus on the within-country governance effects of local insti- tutions to avoid the problems of endogeneity, missing variables, and unobserved heterogeneity common in the institutions literature. I show that different colonial tax institutions within Nigeria implemented by the British for reasons exogenous to local conditions led to different present day quality of governance. People living in areas where the colonial tax system required more bureaucratic capacity are much happier with their government, and receive more compe- tent government services, than people living in nearby areas where colonialism did not build bureaucratic capacity. Author's Note: I would like to thank David Laitin, Adam Przeworski, Shanker Satyanath and David Stasavage for their invaluable advice, as well as all the participants in the NYU predissertation seminar. All errors, of course, remain my own. Do local institutions matter? Can diverse local institutions persist within a single country or will they be driven to convergence? Do decisions about local government structure made by colonial governments a century ago matter today? This paper addresses these issues by looking at local institutions and local public goods provision in Nigeria. -

Lagos Property Market Consensus Report (H1 2020)

Lagos State Branch C H A N G IN G T H E SK YL INES Lagos Property Market Consensus Report H1 2020 A consensus of 178 Estate Surveyors & Valuers and Property Professionals in Lagos, Nigeria Lagos State Branch From the Branch Chairman's Desk 1 Dotun Bamigbola FNIVS, FRICS August, 2020 Chairman, NIESV Lagos State Branch The Data Agenda from 30 major neighbourhoods across Lagos State. Data is the singular most important missing factor in the Nigerian real estate The report, of course, has come at a market over the years. challenging time with the closure of the world economy, Nigeria inclusive, due to the While most advanced economies have lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic, moved ahead with the availability of big which is currently being eased out. data, for development and investment decision making by both public and private The earlier prediction that the Nigerian real sector players in real estate and housing, estate sector was expected to grow at 2.65 the Nigerian market still suffers from a percent in 2020, has now been distorted by dearth of data availability. the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, the initial plan for a quarterly release of this With the real estate sector still contributing report has also been affected, hence the H1 low to Nigeria's GDP at 7% and in view of 2020 report which covers major 30 the expected growth by all players in neighourhoods in Lagos State, categorised private and public sectors over the years, under seven (7) zones. there is need for data to aid the growth of this all-important sector of the economy. -

CIFORB Country Profile – Nigeria

CIFORB Country Profile – Nigeria Demographics • Nigeria has a population of 186,053,386 (July 2016 estimate), making it Africa's largest and the world's seventh largest country by population. Almost two thirds of its population (62 per cent) are under the age of 25 years, and 43 per cent are under the age of 15. Just under half the population lives in urban areas, including over 21 million in Lagos, Africa’s largest city and one of the fastest-growing cities in the world. • Nigeria has over 250 ethnic groups, the most populous and politically influential being Hausa-Fulani 29%, Yoruba 21%, Igbo (Ibo) 18%, Ijaw 10%, Kanuri 4%, Ibibio 3.5%, Tiv 2.5%. • It also has over 500 languages, with English being the official language. Religious Affairs • The majority of Nigerians are (mostly Sunni) Muslims or (mostly Protestant) Christians, with estimates varying about which religion is larger. There is a significant number of adherents of other religions, including indigenous animistic religions. • It is difficult and perhaps not sensible to separate religious, ethnic and regional divides in Nigerian domestic politics. In simplified terms, the country can be broken down between the predominantly Hausa-Fulani and Kunari, and Muslim, northern states, the predominantly Igbo, and Christian, south-eastern states, the predominantly Yoruba, and religiously mixed, central and south-western states, and the predominantly Ogoni and Ijaw, and Christian, Niger Delta region. Or, even more simply, the ‘Muslim north’ and the ‘Christian south’ – finely balanced in terms of numbers, and thus regularly competing for ‘a winner-take-all fight for presidential power between regions.’1 Although Nigeria’s main political parties are pan-national and secular in character, they have strong regional, ethnic and religious patterns of support. -

Revisiting the Budgetary Deficit Factor in the 1914 Amalgamation of Northern and Southern Protectorates: a Case Study of Zaria Province, 1903-1914

International Journal of Liberal Arts and Social Science Vol. 5 No. 9 December 2017 Revisiting the Budgetary Deficit Factor in the 1914 Amalgamation of Northern and Southern Protectorates: A Case Study of Zaria Province, 1903-1914 Dr Attahiru Ahmad SIFAWA Department of History, Faculty of Arts and social sciences, Sokoto State University Sokoto, Nigeria Email: [email protected] Dr SIRAJO Muhammad Sokoto Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies Sokoto State University, Sokoto, Nigeria Murtala MARAFA Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Sokoto State University, Sokoto, Nigeria Email: [email protected] Corresponding Author: Dr Attahiru Ahmad SIFAWA Sponsored by: Tertiary Education Trust Fund, Nigeria 1 International Journal of Liberal Arts and Social Science ISSN: 2307-924X www.ijlass.org Abstract One of the widely propagated notion on the British Administration of Northern Nigeria, and in particular, the 1914 Amalgamation of Northern and Southern protectorates was that the absence of seaboard and custom duties therefrom, and other sources of revenue, made the protectorate of Northern Nigeria depended mostly on direct taxation as its sources of revenue. The result was the inadequacy of the locally generated revenue to meet even the half of the region’s financial expenditure for over 10 years. Consequently, the huge budgetary deficit from the North had to be met with grant – in-aid which averaged about a quarter of a million sterling pounds from the British tax payers’ money annually. Northern Nigeria was thus amalgamated with Southern Nigeria in order to benefit from the latter’s huge budgetary surpluses and do away with imperial grant –in- aid from Britain. -

Diatoms and Dinoflagellates of an Estuarine Creek in Lagos

JournalSci. Res. Dev., 2005/2006, Vol. 10,73‐82 Diatoms and Dinoflagellates of an Estuarine Creek in Lagos. I.C. Onyema*, D.I. Nwankwo and T. Oduleye Department of Marine Sciences, University of Lagos, Akoka‐Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria. ABSTRACT The diatoms and dinoflagellates phytoplankton of an estuarine creek in Lagos was investigated at two stations between July and December, 2004. A total of 37 species centric diatom (18 species) pennate diatoms (12 species) and 7 species of dinoflagellates were recorded. Values of species diversity (1 ‐ 14), abundance (10 ‐ 800 individuals), species richness (0 ‐ 2.40) and Shannon and Weiner index (0 ‐ 2.8f) were higher in the wet period (July ‐ October) than the dry season (November ‐ December). These bio‐indices were higher in station A than Bfor most of the study period. Almost all the diatoms and dinoflagellates recorded for this investigation have been reported by earlier workers for the Lagos lagoon, associated tidal creeks and offshore Lagos. The source of recruitment of the lagoonal dinoflagellates is probably the adjacent sea as most reported species were warm water oceanic forms. Keywords: diatoms, dinoflagellates, plankton, hydrology, salinity. INTRODUCTION In Nigeria there are few studies on the diatoms and dinoflagellates of marine and coastal aquatic ecosystems. Some of these studies are Olaniyan (1957), Nwankwo (1990a), Nwankwo and Kasumu‐Iginla (1997), Nwankwo (1991) and Nwankwo (1997). Other works such as Chindah and Pudo (1991), Nwankwo (1986, 1996), Chindah (1998), Kadiri (1999), Onyema et al. (2003, 2007), Onyema (2007, 2008) have investigated phytoplankton assemblages and pointed out the dominance of diatoms. Diatoms and dinoflagellates are important components of the photosynthetic organisms that form the base of the aquatic food chain (Davis, 1955; Sverdrop et al., 2003).