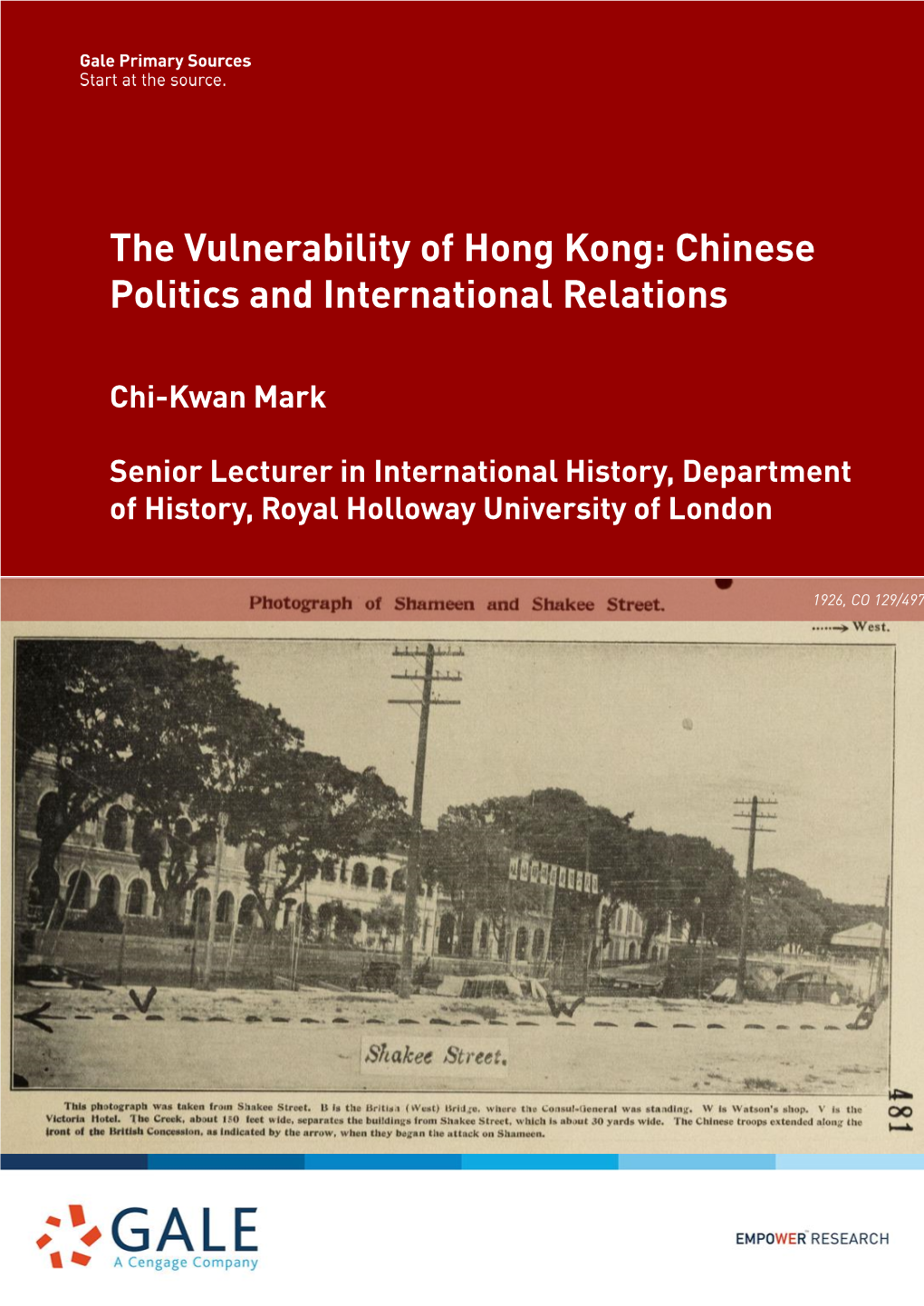

The Vulnerability of Hong Kong: Chinese Politics and International Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Icons, Culture and Collective Identity of Postwar Hong Kong

Intercultural Communication Studies XXII: 1 (2013) R. MAK & C. CHAN Icons, Culture and Collective Identity of Postwar Hong Kong Ricardo K. S. MAK & Catherine S. CHAN Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong S.A.R., China Abstract: Icons, which take the form of images, artifacts, landmarks, or fictional figures, represent mounds of meaning stuck in the collective unconsciousness of different communities. Icons are shortcuts to values, identity or feelings that their users collectively share and treasure. Through the concrete identification and analysis of icons of post-war Hong Kong, this paper attempts to highlight not only Hong Kong people’s changing collective needs and mental or material hunger, but also their continuous search for identity. Keywords: Icons, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Chinese, 1997, values, identity, lifestyle, business, popular culture, fusion, hybridity, colonialism, economic takeoff, consumerism, show business 1. Introduction: Telling Hong Kong’s Story through Icons It seems easy to tell the story of post-war Hong Kong. If merely delineating the sky-high synopsis of the city, the ups and downs, high highs and low lows are at once evidently remarkable: a collective struggle for survival in the post-war years, tremendous social instability in the 1960s, industrial take-off in the 1970s, a growth in economic confidence and cultural arrogance in the 1980s and a rich cultural upheaval in search of locality before the handover. The early 21st century might as well sum up the development of Hong Kong, whose history is long yet surprisingly short- propelled by capitalism, gnawing away at globalization and living off its elastic schizophrenia. -

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

Writing Home from Around the World, 1926–1927

Writing Home from Around the World, 1926–1927 A keen and amused observer, Tom Johnson is an articulate and conscien- tious letter writer. The reader has the feeling he was writing for himself as much as his family as he makes sentences and paragraphs of his impressions of the world at the height of colonialism. By THOMAS H. JOHNSON Edited with an introduction by LAURA JOHNSON WATERMAN y father, Thomas H. Johnson, the writer of these letters, was born in 1902 on the Connecticut River Valley farm known as Stone Cliff, located one mile north of the vil- Mlage of Bradford. In 1926, upon his graduation from Williams College, Tom Johnson embarked on a world cruise that was to last the length of a school year—September to May. He had been invited to teach Eliza- bethan Drama and American Literature (subjects he soon found to be not particularly relevant) on the fi rst ever student travel experiment. This was launched on a large scale with over fi fty faculty and four hun- dred and fi fty students, one hundred and twenty of them women. A. J. McIntosh, president of the University Travel Association, saw this as an opportunity to combine formal education with travel, and orga- nized the adventure by reaching out to colleges across the country. The project became known as the Floating University and was considered . LAURA JOHNSON WATERMAN is the author of Losing the Garden (2005), a memoir of thirty years of homesteading in East Corinth, Vermont. She co-authored with her late husband, Guy Waterman, fi ve books on the history of climbing the moun- tains of the Northeast and related environmental issues, among them, Forest and Crag (1989), Backwoods Ethics (1993), and Wilderness Ethics (1993). -

Modern Hong Kong

Modern Hong Kong Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History Modern Hong Kong Steve Tsang Subject: China, Hong Kong, Macao, and/or Taiwan Online Publication Date: Feb 2017 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.280 Abstract and Keywords Hong Kong entered its modern era when it became a British overseas territory in 1841. In its early years as a Crown Colony, it suffered from corruption and racial segregation but grew rapidly as a free port that supported trade with China. It took about two decades before Hong Kong established a genuinely independent judiciary and introduced the Cadet Scheme to select and train senior officials, which dramatically improved the quality of governance. Until the Pacific War (1941–1945), the colonial government focused its attention and resources on the small expatriate community and largely left the overwhelming majority of the population, the Chinese community, to manage themselves, through voluntary organizations such as the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. The 1940s was a watershed decade in Hong Kong’s history. The fall of Hong Kong and other European colonies to the Japanese at the start of the Pacific War shattered the myth of the superiority of white men and the invincibility of the British Empire. When the war ended the British realized that they could not restore the status quo ante. They thus put an end to racial segregation, removed the glass ceiling that prevented a Chinese person from becoming a Cadet or Administrative Officer or rising to become the Senior Member of the Legislative or the Executive Council, and looked into the possibility of introducing municipal self-government. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster

Mainstream or Alternative? The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster so Ming Hang A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Government and Public Administration © The Chinese University of Hong Kong June 2005 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. 卜二,A館書圆^^ m 18 1 KK j|| Abstract Theoretically, public broadcaster and commercial broadcaster are set up and run by two different mechanisms. Commercial broadcaster, as a proprietary organization, is believed to emphasize on maximizing the profit while the public broadcaster, without commercial considerations, is usually expected to achieve some objectives or goals instead of making profits. Therefore, the contribution by public broadcaster to the society is usually expected to be different from those by commercial broadcaster. However, the public broadcasters are in crisis around the world because of their unclear role in actual practice. Many politicians claim that they cannot find any difference between the public broadcasters and the commercial broadcasters and thus they asserted to cut the budget of public broadcasters or even privatize all public broadcasters. Having this unstable situation of the public broadcasting, the role or performance of the public broadcasters in actual practice has drawn much attention from both policy-makers and scholars. Empirical studies are divergent on whether there is difference between public and commercial broadcaster in actual practice. -

The Kodak Magazine; Vol. 7, No. 7; Dec. 1926

December 1926 Published in the interests of the men and women of the Kodak organi3ation by Eastman Kodak Company. Rochester. N. Y. MONTHLY ACCIDENT REPORT OCTOBER, 1926 Accident Cases Accidents per 1000 PLANT Employees 19~6 19~5 19~6 19~5 Kodak Office . .. .. .. 1 0 .77 0 Camera Works . .. ·. ... 7 2 2 .38 1.25 Hawk-Eye Works .. ... 0 1 0 3 .12 Kodak Park Works . 21 15 3.25 2.58 --- Total- Rochester Plants 29 18 2 .59 1.97 I I NATURE OF ACCIDENTS DURING MONTH 13 cases of injury through bruises, burns and lacerations, etc. 4 cases of injury through falling and slipping. l cases of injury through falling material. 1 case of injury through stepping on nail. 1 case of injury through sprains and strains. 2 cases of injury around press. 2 cases of injury through saw. 2 cases of injury through machine of special nature. 29 Employees' accident cases during month. A Merry Christmas and a Happy New rear to every one ofyou AT THE LANDING By Mary Callaghan, member, Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences From a recent Kodak Park Camera Club Interchange Exhibit VoL. VII DECEMBER, 19~6 No.7 VALUE $1.98 "ARAG and a bone and a hank of hair." do without iron? Of what use would your How is that for a description of a muscles and nerves be without all three woman? Recently comes this as the make and ten or so others besides? up of an "average man" (I suspect it fits Did you ever have that "run-down" an "average woman" as well)-"Four and feeling and go to your doctor and have a half pails of water, including the blood him tell you to build up your blood? And which .courses his veins, twenty-three whe.n you asked him how to do it you pounds offat, one-eighth of an ounce of iron, found that part of the prescription meant one-eighth of ~n ounce of sugar, one-half to eat foods which had plenty lime, iron, of an ounce of salt, one pound of lime, a phosphorus and the ten or so other min little potash, phosphorus, sulphur, etc. -

Gtr Ne25 408.Pdf

Perception of High-density Living in Hong Kong by LAWRENCE H. TRAVERS, assistant professor, State University of New York, College of Arts and Science, Oswego, N. Y. ABSTRACT.-Analysis of the Hong Kong experience of adaptation to urban living can provide insights into some of the problems that can be expected to occur in the rapidly expanding cities of the Third World. Population densities in Hong Kong are among the highest in the world, exceeding 400,000 persons per square mile in parts of Kowloon. Research based upon residence in a worker's dormitory and interviews with workers reveals a variety of adaptive strategies employed by people to cope with the stress of the crowded urban environment. An understanding of the individual's ability to adjust to the stress of high-density living must consider the meaning of density as a concept in the culture in addition to social and cultural norms. DESPITEDECADES OF CONCERN informal conversations with many of the about the possible effects of high residents, and through structured inter- living densities upon human behavior, views with cooperative individuals. we know very little about mankind's ability to adapt to crowded conditions. ACTUAL POPULATION DENSITIES Fears persist that the presence of a be- Densities in Hong Kong are among havioral sink among rat populations the highest in the world. In 1971 the forced to live in very crowded quarters Mongkok area in Kowloon had a density (Calhoun 1962) might have a correlate of 154,677 persons per square kilometer in human populations. Perhaps rather (or 400,612 persons per square mile) than simply observing human behavior which is almost five times the living den- in dense conditions, we might more sity of Manhattan Island (H. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

The Diminishing Power and Democracy of Hong Kong: an Analysis of Hong Kong's Umbrella Movement and the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College Summer 2021 The Diminishing Power and Democracy of Hong Kong: An Analysis of Hong Kong's Umbrella Movement and the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement Xiao Lin Kuang Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Other International and Area Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kuang, Xiao Lin, "The Diminishing Power and Democracy of Hong Kong: An Analysis of Hong Kong's Umbrella Movement and the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement" (2021). University Honors Theses. Paper 1126. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.1157 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The diminishing power and democracy of Hong Kong: an analysis of Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement and the Anti-extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement by Xiao Lin Kuang An undergraduate honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts In University Honors And International Development Studies And Chinese Thesis Adviser Maureen Hickey Portland State University 2021 The diminishing power and democracy of Hong Kong Kuang 1 Abstract The future of Hong Kong – one of the most valuable economic port cities in the world – has been a key political issue since the Opium Wars (1839—1860). -

1O1O Next GTM Around the Island Race 2009

for immediate release 7 November 2017 Turkish Airlines Around the Island Race Sunday 12 November Over 230 entries have been received for the 2017 edition of the Turkish Airlines Around the Island Race which will take place this Sunday 12 November. This year, the Title Sponsor is Star Alliance member, Turkish Airlines. The partnership between Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club (“Best Asian Yacht Club”) and Turkish Airlines (“The airline that flies to more countries than any other airline and the Skytrax award winner for four key categories in 2017”) will bring a lot of excitement to the Around the Island Race as the fleet flies around Hong Kong Island. Turkish Airlines is also sponsoring an Around the Island Race photography competition which will see one lucky person being chosen to win a return business class ticket from Hong Kong to any worldwide destination* operated by Turkish Airlines. Serhat Sari, General Manager of Turkish Airlines Hong Kong, said “we are very excited to be the Title Sponsor for Around the Island Race - the biggest public sailing event of the year in Hong Kong.” Mr. Sari continued, “This year is our 15th anniversary of operation in Hong Kong and we hope that through this sponsorship engagement with the sailing participants and a campaign with the public, will bring Turkish Airlines’ brand and service commitment even closer to this Asia’s World City. Anyone with the sight of the fleet from right at the waterfront in the harbor or from up on the Peak, or perhaps somewhere at the South Side stands a chance to snap that special photo and win.” This event is Hong Kong’s largest celebration of sail and will see Victoria Harbour filled to the brim with sailboats, before they set off on the 26nm circumnavigation of Hong Kong island. -

Newly Completed Babington Hill Residences at Mid-Levels West Now on the Market

Love・Home Newly completed Babington Hill residences at Mid-Levels West now on the market Babington Hill, the latest SHKP residential project in the traditional Island West district, is nestled amidst lush greenery in close proximity to excellent transport links and famous schools. These residences have been finished to exacting standards and boast fashionable interiors with a distinctive appearance. Units are now on the market receiving an encouraging response. The best of everything Babington Hill is a rare new development for the area offering a range of 79 quality residential units with two to four bedroom layouts, all with outdoor areas, such as a balcony, utility platform, flat roof and/or roof to create an open, comfortable living environment. The development benefits from the use of high-quality building materials. The exterior design features a large number of glass curtain walls to provide transparency and create a spacious feeling. The clean and comfortable interior includes a luxurious private clubhouse equipped with a gym and an outdoor swimming pool. Famous schools and convenient transport The Development is situated next to the University of Hong Kong and Dean's Residence in the Mid-Levels of Hong Kong Island. It is near the Lung Fu Shan hiking trails, which provides quick and easy access to nature as well as a sanctuary of peace and tranquility. The area is home to a traditional and well-established network of elite schools, such as St. Paul's College, St. Stephen's Girls' College and St. Joseph's College, all of which provide excellent scholastic environments for the next generation to learn and thrive.