Albuquerque Museum Oral History Project Johnny J. Armijo November 26, 2002 This Interview Was Conducted As Part of a Project By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the Governor's Commission to Rebuild Texas

EYE OF THE STORM Report of the Governor’s Commission to Rebuild Texas John Sharp, Commissioner BOARD OF REGENTS Charles W. Schwartz, Chairman Elaine Mendoza, Vice Chairman Phil Adams Robert Albritton Anthony G. Buzbee Morris E. Foster Tim Leach William “Bill” Mahomes Cliff Thomas Ervin Bryant, Student Regent John Sharp, Chancellor NOVEMBER 2018 FOREWORD On September 1 of last year, as Hurricane Harvey began to break up, I traveled from College Station to Austin at the request of Governor Greg Abbott. The Governor asked me to become Commissioner of something he called the Governor’s Commission to Rebuild Texas. The Governor was direct about what he wanted from me and the new commission: “I want you to advocate for our communities, and make sure things get done without delay,” he said. I agreed to undertake this important assignment and set to work immediately. On September 7, the Governor issued a proclamation formally creating the commission, and soon after, the Governor and I began traveling throughout the affected areas seeing for ourselves the incredible destruction the storm inflicted Before the difficulties our communities faced on a swath of Texas larger than New Jersey. because of Harvey fade from memory, it is critical that Since then, my staff and I have worked alongside we examine what happened and how our preparation other state agencies, federal agencies and local for and response to future disasters can be improved. communities across the counties affected by Hurricane In this report, we try to create as clear a picture of Harvey to carry out the difficult process of recovery and Hurricane Harvey as possible. -

A FAILURE of INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina

A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina U.S. House of Representatives 4 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Union Calendar No. 00 109th Congress Report 2nd Session 000-000 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Report by the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoacess.gov/congress/index.html February 15, 2006. — Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U. S. GOVERNMEN T PRINTING OFFICE Keeping America Informed I www.gpo.gov WASHINGTON 2 0 0 6 23950 PDF For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 COVER PHOTO: FEMA, BACKGROUND PHOTO: NASA SELECT BIPARTISAN COMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE THE PREPARATION FOR AND RESPONSE TO HURRICANE KATRINA TOM DAVIS, (VA) Chairman HAROLD ROGERS (KY) CHRISTOPHER SHAYS (CT) HENRY BONILLA (TX) STEVE BUYER (IN) SUE MYRICK (NC) MAC THORNBERRY (TX) KAY GRANGER (TX) CHARLES W. “CHIP” PICKERING (MS) BILL SHUSTER (PA) JEFF MILLER (FL) Members who participated at the invitation of the Select Committee CHARLIE MELANCON (LA) GENE TAYLOR (MS) WILLIAM J. -

BREAKING ALL the RULES As Recorded by Ozzy Osbourne (From the 1988 Album "No Rest for the Wicked")

BREAKING ALL THE RULES As recorded by Ozzy Osbourne (from the 1988 Album "No Rest For The Wicked") Transcribed by /\X/\M Words by Ozzy Osbourne, Bob Daisley, Zakk Wylde, J.Sinclair & Randy Castillo Music by Ozzy Osbourne, Bob Daisley, Zakk Wylde, J.Sinclair & Randy Castillo All Guitars Tuned Down 1/2 Step A Intro P = 120 1 j k V V V R I J V V V } } V V } } V } } V V P V VgV f } V V V } } V V } } V } } V V V } V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V Gtr I 1/2 P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. M 0 0 0 T 0 0 0 9 9 0 4 2 4 0 A 7 9 9 x x 5 7 x x 5 x x 7 2 4 0 x B 7 7 7 x x 3 5 x x 3 x x 5 2 x 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 sl. 6 R I V } } V V } } V } } V V P V V gV f } V } } V V } } V } } V V V } V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V 1/2 P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. M T 4 2 4 0 A 2 x x 5 7 x x 5 x x 7 9 4 0 x B 2 x x 3 5 x x 3 x x 5 7 x 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 sl. -

Music 6581 Songs, 16.4 Days, 30.64 GB

Music 6581 songs, 16.4 days, 30.64 GB Name Time Album Artist Rockin' Into the Night 4:00 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Caught Up In You 4:37 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Hold on Loosely 4:40 Wild-Eyed Southern Boys .38 Special Voices Carry 4:21 I Love Rock & Roll (Hits Of The 80's Vol. 4) 'Til Tuesday Gossip Folks (Fatboy Slimt Radio Mix) 3:32 T686 (03-28-2003) (Elliott, Missy) Pimp 4:13 Urban 15 (Fifty Cent) Life Goes On 4:32 (w/out) 2 PAC Bye Bye Bye 3:20 No Strings Attached *NSYNC You Tell Me Your Dreams 1:54 Golden American Waltzes The 1,000 Strings Do For Love 4:41 2 PAC Changes 4:31 2 PAC How Do You Want It 4:00 2 PAC Still Ballin 2:51 Urban 14 2 Pac California Love (Long Version 6:29 2 Pac California Love 4:03 Pop, Rock & Rap 1 2 Pac & Dr Dre Pac's Life *PO Clean Edit* 3:38 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2006 2Pac F. T.I. & Ashanti When I'm Gone 4:20 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3:58 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Bailen (Reggaeton) 3:41 Tropical Latin September 2002 3-2 Get Funky No More 3:48 Top 40 v. 24 3LW Feelin' You 3:35 Promo Only Rhythm Radio July 2006 3LW f./Jermaine Dupri El Baile Melao (Fast Cumbia) 3:23 Promo Only - Tropical Latin - December … 4 En 1 Until You Loved Me (Valentin Remix) 3:56 Promo Only: Rhythm Radio - 2005/06 4 Strings Until You Love Me 3:08 Rhythm Radio 2005-01 4 Strings Ain't Too Proud to Beg 2:36 M2 4 Tops Disco Inferno (Clean Version) 3:38 Disco Inferno - Single 50 Cent Window Shopper (PO Clean Edit) 3:11 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2005 50 Cent Window Shopper -

Instrumental Song Gospel Song Mariachi Song Vocal Duo Bilingual Song Mark Ipiotis Award

NMHMA Hispano Music Awards Nominees-2016 . SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Instrumental El Zopilote Mojado Mario Romero Gunshot Los Serranos Y Familia Song Polka Melodia Grupo Melodia of The Year Polka Zapatos Gony, Barbara & The Boyz Valse De Mis Padres The Dave Maestas Band SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Gospel Desde Que Dios Amanece Marcelina Velasquez Mundo Malo Cuarenta Y Cinco Song No Hay Dios Como Tu Jerry Dean & Alex Garcia of the Year Pescador De Hombres Al Hurricane Jr. Te Vas Angel Mio Bobby Madrid & Christina Perea SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Mariachi Cielito Lindo Huasteco Mariachi Sonidos Del Monte Song El Jinete Antonio Reyna of The Year El Mundo Es Mio Eddie Y Vengancia Te Vas Angel Mio Christina Perea Y Bobby Madrid VOCAL DUO SONG TITLE Vocal Christina Perea & Anita Lopez Flor De Las Flores Darren Cordova & Matthew Martinez Dos Hombres Y Un Destino Duo Jerry Dean & Christian Sanchez Mi Padrecito of The Year Severo Martinez & Jenna Baila Conmigo Tanya Griego & Justin Anaya Regresa Muy Pronto A Mi SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Bilingual Before The Next Tear Drop Falls Andrew Gonzales En El Mistico Black Pearl Band NM Song I Need to Know-Aye Dimelo Latino Persuasion of The Year Please Don’t Go Chelsea Chavez Wasted Days & Wasted Nights Miguel Timoteo NOMINEE Mark Glenda Martinez/KDCE Radio Ipiotis Kevin Otero-KANW Radio Mariachi Mike/KDCE Radio Award Mike Baca/KFUN Radio Norberto Martinez/KXMT Radio NMHMA Hispano Music Awards Nominees-2016 . SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Conjunto Chiquito Pero Picoso Rhythm Divine Norteño La Mala Vida Latino Persuasion Song Ojitos Verdes Eddie Y Venganzia of The Year Que Te Faltaba Andrew Gonzales Soy Toda Tuya Tanya Griego SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Crossover Chile Verde Rock Lluvia Negra Band El Retrato Chris Arellano Song En El Mistico Black Pearl Band NM of The Year I Got Mexico Cuarenta Y Cinco Please Don’t Go Chelsea Chavez SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Cumbia Doña Juana Dwayne Ortega Band El Regañado Cuarenta Y Cinco Song La Roncona Al Hurricane Jr. -

Ebook I Am Ozzy Freeware "They've Said Some Crazy Things About Me Over the Years

Ebook I Am Ozzy Freeware "They've said some crazy things about me over the years. I mean, okay: 'He bit the head off a bat.' Yes. 'He bit the head off a dove.' Yes. But then you hear things like, 'Ozzy went to the show last night, but he wouldn't perform until he'd killed fifteen puppies . .' Now me, kill fifteen puppies? I love puppies. I've got eighteen of the f**king things at home. I've killed a few cows in my time, mind you. And the chickens. I shot the chickens in my house that night. It haunts me, all this crazy stuff. Every day of my life has been an event. I took lethal combinations of booze and drugs for thirty f**king years. I survived a direct hit by a plane, suicidal overdoses, STDs. I've been accused of attempted murder. Then I almost died while riding over a bump on a quad bike at f**king two miles per hour. People ask me how come I'm still alive, and I don't know what to say. When I was growing up, if you'd have put me up against a wall with the other kids from my street and asked me which one of us was gonna make it to the age of sixty, which one of us would end up with five kids and four grandkids and houses in Buckinghamshire and Beverly Hills, I wouldn't have put money on me, no f**king way. But here I am: ready to tell my story, in my own words, for the first time. -

Black Sabbath the Complete Guide

Black Sabbath The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 17 May 2010 12:17:46 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Black Sabbath 1 The members 23 List of Black Sabbath band members 23 Vinny Appice 29 Don Arden 32 Bev Bevan 37 Mike Bordin 39 Jo Burt 43 Geezer Butler 44 Terry Chimes 47 Gordon Copley 49 Bob Daisley 50 Ronnie James Dio 54 Jeff Fenholt 59 Ian Gillan 62 Ray Gillen 70 Glenn Hughes 72 Tony Iommi 78 Tony Martin 87 Neil Murray 90 Geoff Nicholls 97 Ozzy Osbourne 99 Cozy Powell 111 Bobby Rondinelli 118 Eric Singer 120 Dave Spitz 124 Adam Wakeman 125 Dave Walker 127 Bill Ward 132 Related bands 135 Heaven & Hell 135 Mythology 140 Discography 141 Black Sabbath discography 141 Studio albums 149 Black Sabbath 149 Paranoid 153 Master of Reality 157 Black Sabbath Vol. 4 162 Sabbath Bloody Sabbath 167 Sabotage 171 Technical Ecstasy 175 Never Say Die! 178 Heaven and Hell 181 Mob Rules 186 Born Again 190 Seventh Star 194 The Eternal Idol 197 Headless Cross 200 Tyr 203 Dehumanizer 206 Cross Purposes 210 Forbidden 212 Live Albums 214 Live Evil 214 Cross Purposes Live 218 Reunion 220 Past Lives 223 Live at Hammersmith Odeon 225 Compilations and re-releases 227 We Sold Our Soul for Rock 'n' Roll 227 The Sabbath Stones 230 Symptom of the Universe: The Original Black Sabbath 1970–1978 232 Black Box: The Complete Original Black Sabbath 235 Greatest Hits 1970–1978 237 Black Sabbath: The Dio Years 239 The Rules of Hell 243 Other related albums 245 Live at Last 245 The Sabbath Collection 247 The Ozzy Osbourne Years 249 Nativity in Black 251 Under Wheels of Confusion 254 In These Black Days 256 The Best of Black Sabbath 258 Club Sonderauflage 262 Songs 263 Black Sabbath 263 Changes 265 Children of the Grave 267 Die Young 270 Dirty Women 272 Disturbing the Priest 273 Electric Funeral 274 Evil Woman 275 Fairies Wear Boots 276 Hand of Doom 277 Heaven and Hell 278 Into the Void 280 Iron Man 282 The Mob Rules 284 N. -

November 1987

EDUCATION DRIVER'S SEAT Playing In Two or Four by Ed Shaughnessy 48 IN THE STUDIO Those First Sessions by Craig Krampf 50 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC Two-Surface Riding: Part 1 by Rod Morgenstein 52 CORPS SCENE Flim-Flams by Dennis DeLucia 66 MASTER CLASS Portraits in Rhythm: Etude #9 by Anthony J. Cirone 76 ELECTRONIC INSIGHTS MIDI System Interconnections by Jim Fiore 78 ROCK CHARTS Carl Palmer: "Brain Salad Surgery" by William F. Miller 80 Cover Photo by Michael S. Jachles ROCK PERSPECTIVES Ringo Starr: The Middle Period by Kenny Aronoff 90 RANDY CASTILLO JAZZ DRUMMERS' WORKSHOP Imagine this: You are at home with a broken leg, and you get a Your Drum Setup call to audition for Ozzy Osbourne. That happened to Randy by Peter Erskine 94 Castillo, and he got the gig. Here, he discusses such topics as SOUTH OF THE BORDER his double bass drum work and showmanship in drumming. Latin Rhythms On Drumset by John Santos 96 by Robyn Flans 16 CONCEPTS The Natural Drummer CURT CRESS by Roy Burns 104 Known for his work in Germany's recording studios and his CLUB SCENE playing with the band Passport, Curt Cress has also recorded Hecklers And Hasslers with Freddie Mercury, Meatloaf, and Billy Squier. Curt by Rick Van Horn 106 explains why the German approach is attracting British and EQUIPMENT American artists and producers. SHOP TALK by Simon Goodwin 22 Evaluating Your Present Drumset by Patrick Foley 68 PRODUCT CLOSE-UP DRUMMERS OF Pearl MLX/BLX Pro Series Drumkits by Bob Saydlowski, Jr 110 CONTEMPORARY ELECTRONIC REVIEW Korg DDD-1 Drum Machine CHRISTIAN MUSIC: by Rick Mattingly 112 NEW AND NOTABLE 124 PART 1 PROFILES John Gates, Art Noble, and Keith Thibodeaux discuss their PORTRAITS work with a variety of Christian music bands, and clarify what Thurman Barker Christian music is and what it is not. -

SAVE the DATE Tv.Org/Overdose - a Panel of Experts Discuss the Drug Epidemic in the U.S., and Offer Solid, Timely Information About Prevention and Treatment

October, 2018 EDUCATION NEWS Sponsored Content: http://wxxi.org/opiods Do No Harm: The Opioid Epidemic: #101 – The Odyssey of Ignorance & Greed - Airs 10/15 at 9 p.m. (repeats 10/21 at 1 p.m.) #102 Ground Zero - Airs 10/21 at 2 p.m. #103 – Rocky Road to Recovery - Airs 10/21 at 3 p.m. Nova – Addiction - http://pbs.org/wgbh/nova/body/ addiction.html - Delve into America's opioid crisis - in a world in which many other diseases can be traced to addictive behavior, how do addictions work, and what can the science of addiction tell us about how we can resolve this dire social issue? Airs 10/17 at 9 p.m. Frontline—Chasing Heroin - https://pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/ film/chasing-heroin/ - Facing a heroin epidemic, America is experimenting with radical new approaches to the drug problem. More Information: https://www2.naz.edu/arts-center/school-shows/ Following four addicts in Seattle, examine U.S. drug policy and what happens when heroin is treated like a public health crisis, not a crime. Airs 10/18 at 9 p.m. (repeats 10/20 at 10 p.m.) Second Opinion Special: Inside the Epidemic - secondopinion- SAVE THE DATE tv.org/overdose - A panel of experts discuss the drug epidemic in the U.S., and offer solid, timely information about prevention and treatment. Airs 10/20 at 5 p.m. Opioids From Inside - There is a person’s story behind every opioid addiction. And each story of addiction has a ripple http://wxxi.org/indielens effect. Opioids from Inside, a WXXI, Blue Sky Project and PBS WORLD production, is a half-hour film that follows the journey of three women, all mothers, who have served time in New York State WXXI is proud to host a neighborhood screening series that jails for opioid-related crimes. -

HM 108 Page 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

1 A MEMORIAL 2 RECOGNIZING THE HISPANIC HERITAGE COMMITTEE FOR ITS 3 COLLABORATION EFFORTS IN PROMOTING GREATER AWARENESS, 4 APPRECIATION AND CULTURAL PRESERVATION OF NEW MEXICO MUSIC 5 AND MARIACHI MUSIC IN NEW MEXICO FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS. 6 7 WHEREAS, New Mexico music stretches back centuries, with 8 roots in thirteenth century pueblo music, and incorporates 9 ranchera, Navajo, country and western folk styles; and 10 WHEREAS, New Mexico music is a unique musical genre, 11 recognized for its up-tempo rhythms, ranchera polka, bolero 12 rhythms and distinctive vocals; and 13 WHEREAS, New Mexico music has been influenced by many 14 legendary New Mexican artists, such as Al Hurricane, Al 15 Hurricane, Jr., Tobias Rene, the Blue Ventures band, Gonzalo, 16 Sparx, Lorenzo Antonio and Darren Cordova; and 17 WHEREAS, mariachi music has New Mexico's historical 18 influence and instills pride in cultural heritage; and 19 WHEREAS, mariachi music is historically known as "la 20 musica de la gente", or music of the people, the common folk, 21 with musical ballads that describe an array of human 22 emotions, including feelings of nostalgia that bring 23 communities together to celebrate life while connecting to 24 the rich traditions of the past; and 25 WHEREAS, the Hispanic heritage committee has identified HM 108 Page 1 1 the decline in popularity of both New Mexico music and 2 mariachi music in New Mexico; 3 NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED BY THE HOUSE OF 4 REPRESENTATIVES OF THE STATE OF NEW MEXICO that the Hispanic 5 heritage committee be recognized -

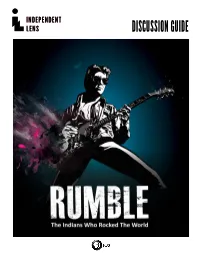

DISCUSSION GUIDE Table of Contents Using This Guide 3

DISCUSSION GUIDE Table of Contents Using This Guide 3 Indie Lens Pop-Up We Are All Neighbors Theme 4 About the Film 5 From the Filmmakers 6 Artist Profiles 8 Background Information 13 What is Indigenous Music? 13 Exclusion and Expulsion 14 Music and Cultural Resilience 15 The Ghost Dance and Wounded Knee 16 Native and African American Alliances 17 Discussion 18 Conversation Starter 18 Post-Screening Discussion Questions 19 Engagement Ideas 20 Potential Partners and Speakers 20 Activities Beyond a Panel 21 Additional Resources 22 Credits 23 DISCUSSION GUIDE RUMBLE: THE INDIANS WHO ROCKED THE WORLD 2 USING THIS GUIDE This discussion guide is a resource to support organizations hosting Indie Lens Pop-Up events for the film RUMBLE: The Indians Who Rocked the World. Developed primarily for facilitators, this guide offers background information and engagement strategies designed to raise awareness and foster dialogue about the integral part Native Americans have played in the evolution of popular music. Viewers of the film can use this guide to think more deeply about the discussion started in RUMBLE and find ways to participate in the national conversation. RUMBLE: The Indians Who Rocked the World is an invitation to come together with neighbors and pay tribute to Native influences on America’s most celebrated music. The film makes its PBS broadcast premiere on the Independent Lens series on January 21, 2019. Indie Lens Pop-Up is a neighborhood series that brings people together for film screenings and community-driven conversations. Featuring documentaries seen on PBS’s Independent Lens, Indie Lens Pop-Up draws local residents, leaders, and organizations together to discuss what matters most, from newsworthy topics to family and relationships. -

Metallimusiikki Musiikkiyhtye & Musiikin Esittã¤J㤠Lista

Metallimusiikki Musiikkiyhtye & Musiikin esittäjä Lista Masterpiece https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/masterpiece-22967514/albums Mikko Härkin https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/mikko-h%C3%A4rkin-1079969/albums Blaze Bayley https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/blaze-bayley-1756800/albums Chainsaw https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/chainsaw-5395589/albums Brats https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/brats-4958082/albums Piet Sielck https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/piet-sielck-69837/albums Machine Men https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/machine-men-498636/albums Dan Nelson https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/dan-nelson-3298514/albums Gotham Road https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/gotham-road-3773639/albums Oliver/Dawson Saxon https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/oliver%2Fdawson-saxon-1092373/albums Stonegard https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/stonegard-12003345/albums Symbols https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/symbols-3507540/albums T & N https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/t-%26-n-2382920/albums Masterstroke https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/masterstroke-5479786/albums Kobus! https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/kobus%21-3643369/albums Saber Tiger https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/saber-tiger-11543506/albums Motör Militia https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/mot%C3%B6r-militia-1718843/albums Tribuzy https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/tribuzy-3998670/albums JonnyX and the Groadies https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/jonnyx-and-the-groadies-6275706/albums