The Need for a National Hurricane Initiative Hearing Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation Un

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Featured News

October 31, 2017 Volume 36, Issue 21 Subscribe to Update In This Issue FEATURED NEWS COSSA Joins Societies in Requesting Changes to NIH Clinical Trial Policy CONG RESSIONAL NEWS Rand Paul Introduces Bill to "Reform" Federal Research Grant System Labor, Health and Human Services Subcommittee Holds Hearing on Indirect Costs of Research FEDERAL AG ENCY & ADMINISTRATION NEWS William Beach, Former Budget Committee Economist, Nominated as BLS Commissioner GAO to Study Potential Federal Interference in Science NSF's Statistical Division Seeks Director GAO Report on Firearm Storage Highlights Lack of Federal Funding for Gun Research PUBLICATIONS & COMMUNITY EVENTS CNSTAT Issues Report on Federal Statistics, Multiple Data Sources, and Privacy Protection NDD United Highlights Impacts of Budget Cuts in Faces of Austerity 2.0 Report COSSA MEMBER SPOTLIG HT John Holdren Wins 2018 Moynihan Prize SRCD Accepting Application for Federal, State Policy Fellowships EVENTS CALENDAR FEATURED NEWS COSSA Joins Societies in Requesting Changes to NIH Clinical Trial Policy In a letter sent to National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director Francis Collins on October 27, COSSA and 21 other scientific societies and associations requested that NIH revisit a new policy that alters the definition of "clinical trials" funded by the agency and institutes new reporting requirements for such research (see COSSA's coverage of this issue). While the letter is supportive of the goal of enhancing transparency of NIH-funded research, including introducing registration and reporting requirements, the signatories express concern that "basic science research is being redefined as a clinical trial at NIH and that "basic science investigators will be unnecessarily burdened with requirements relating to conducting clinical trials that have nothing to do with their own research." The organizations hope to work with NIH leadership to find a solution that addresses the concerns of the basic science community while still improving transparency for true clinical trial research. -

Report of the Governor's Commission to Rebuild Texas

EYE OF THE STORM Report of the Governor’s Commission to Rebuild Texas John Sharp, Commissioner BOARD OF REGENTS Charles W. Schwartz, Chairman Elaine Mendoza, Vice Chairman Phil Adams Robert Albritton Anthony G. Buzbee Morris E. Foster Tim Leach William “Bill” Mahomes Cliff Thomas Ervin Bryant, Student Regent John Sharp, Chancellor NOVEMBER 2018 FOREWORD On September 1 of last year, as Hurricane Harvey began to break up, I traveled from College Station to Austin at the request of Governor Greg Abbott. The Governor asked me to become Commissioner of something he called the Governor’s Commission to Rebuild Texas. The Governor was direct about what he wanted from me and the new commission: “I want you to advocate for our communities, and make sure things get done without delay,” he said. I agreed to undertake this important assignment and set to work immediately. On September 7, the Governor issued a proclamation formally creating the commission, and soon after, the Governor and I began traveling throughout the affected areas seeing for ourselves the incredible destruction the storm inflicted Before the difficulties our communities faced on a swath of Texas larger than New Jersey. because of Harvey fade from memory, it is critical that Since then, my staff and I have worked alongside we examine what happened and how our preparation other state agencies, federal agencies and local for and response to future disasters can be improved. communities across the counties affected by Hurricane In this report, we try to create as clear a picture of Harvey to carry out the difficult process of recovery and Hurricane Harvey as possible. -

A FAILURE of INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina

A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina U.S. House of Representatives 4 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Union Calendar No. 00 109th Congress Report 2nd Session 000-000 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Report by the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoacess.gov/congress/index.html February 15, 2006. — Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U. S. GOVERNMEN T PRINTING OFFICE Keeping America Informed I www.gpo.gov WASHINGTON 2 0 0 6 23950 PDF For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 COVER PHOTO: FEMA, BACKGROUND PHOTO: NASA SELECT BIPARTISAN COMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE THE PREPARATION FOR AND RESPONSE TO HURRICANE KATRINA TOM DAVIS, (VA) Chairman HAROLD ROGERS (KY) CHRISTOPHER SHAYS (CT) HENRY BONILLA (TX) STEVE BUYER (IN) SUE MYRICK (NC) MAC THORNBERRY (TX) KAY GRANGER (TX) CHARLES W. “CHIP” PICKERING (MS) BILL SHUSTER (PA) JEFF MILLER (FL) Members who participated at the invitation of the Select Committee CHARLIE MELANCON (LA) GENE TAYLOR (MS) WILLIAM J. -

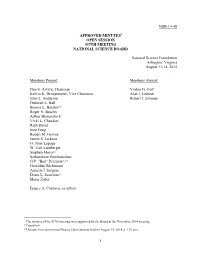

Open Session Minutes, May 2014

NSB-14-48 APPROVED MINUTES1 OPEN SESSION 437TH MEETING NATIONAL SCIENCE BOARD National Science Foundation Arlington, Virginia August 13-14, 2014 Members Present: Members Absent: Dan E. Arvizu, Chairman Vinton G. Cerf Kelvin K. Droegemeier, Vice Chairman Alan I. Leshner John L. Anderson Robert J. Zimmer Deborah L. Ball Bonnie L. Bassler** Roger N. Beachy Arthur Bienenstock Vicki L. Chandler Ruth David Inez Fung Robert M. Groves James S. Jackson G. Peter Lepage W. Carl Lineberger Stephen Mayo** Sethuraman Panchanathan G.P. “Bud” Peterson*,** Geraldine Richmond Anneila I. Sargent Diane L. Souvaine* Maria Zuber France A. Córdova, ex officio 1 The minutes of the 437th meeting were approved by the Board at the November 2014 meeting. *Consultant **Absent from reconvened Plenary Open Session held on August 14, 2014 at 1:30 p.m. 1 The National Science Board (Board, NSB) convened in Open Session on Wednesday, August 13, 2014 at 11:00 a.m. with Dr. Dan Arvizu, Chairman, presiding (Agenda NSB-14-37, Board Book page 307). In accordance with the Government in the Sunshine Act, this portion of the meeting was open to the public. AGENDA ITEM 1: Presentation by Waterman Award Recipient Dr. Feng Zhang, recipient of the 2014 Alan T. Waterman Award, gave a presentation to the Board, entitled, “Development and Application of Crispr-cas9 for Genome Editing” (Board Book Addendum). Dr. Zhang is a W. M. Keck Career Development Professor of Biomedical Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Core Member at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard University, and Investigator at the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT (Board Book page 309). -

Featured News

June 23, 2020 Volume 39, Issue 13 Subscribe to COSSA Washington Update | Subscribe to Members-Only Emails from COSSA In This Issue FEATURED NEWS White House Issues Ban on Entry of Skilled Foreign Workers Notable COVID-19 Resources COSSA IN ACTION Letters & Statements CONGRESSIONAL NEWS Policing Research Bill Introduced as Congress Continues Focus on Police Reform FEDERAL AGENCY & ADMINISTRATION NEWS Sethuraman Panchanathan Confirmed as Next NSF Director Nomination Opportunities Funding Opportunities Notices & Requests for Comment Recent Reports Open Positions COMMUNITY NEWS & REPORTS SEAN Releases Rapid Consultation on Evaluating Types of COVID-19 Data Scientific Community Responds to Racism and Police Violence through #ShutDownSTEM Campaign Nomination Opportunities COSSA MEMBER SPOTLIGHT SPSP Names New Executive Director EVENTS CALENDAR FEATURED NEWS White House Issues Ban on Entry of Skilled Foreign Workers On June 22, President Trump issued a proclamation further extending restrictions on foreign travel to the United States in order to reduce the competitiveness of the U.S. labor market. The proclamation argues that due to the economic downturn and resulting unemployment caused by the coronavirus pandemic, foreign workers "pose an unusual threat to the employment of American workers." The proclamation prohibits the entry of foreign workers under several visa categories commonly used by science and academic institutions to hire employees with unique skills and specialized training, including H-1B and H-4 visas, for skilled workers and their spouses respectively; J-1 visas, for scholarly and other cultural exchanges; most H-2B visas, for nonagricultural workers; and L-1 visas, for foreign employees of companies to transfer to U.S. locations. -

Music 6581 Songs, 16.4 Days, 30.64 GB

Music 6581 songs, 16.4 days, 30.64 GB Name Time Album Artist Rockin' Into the Night 4:00 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Caught Up In You 4:37 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Hold on Loosely 4:40 Wild-Eyed Southern Boys .38 Special Voices Carry 4:21 I Love Rock & Roll (Hits Of The 80's Vol. 4) 'Til Tuesday Gossip Folks (Fatboy Slimt Radio Mix) 3:32 T686 (03-28-2003) (Elliott, Missy) Pimp 4:13 Urban 15 (Fifty Cent) Life Goes On 4:32 (w/out) 2 PAC Bye Bye Bye 3:20 No Strings Attached *NSYNC You Tell Me Your Dreams 1:54 Golden American Waltzes The 1,000 Strings Do For Love 4:41 2 PAC Changes 4:31 2 PAC How Do You Want It 4:00 2 PAC Still Ballin 2:51 Urban 14 2 Pac California Love (Long Version 6:29 2 Pac California Love 4:03 Pop, Rock & Rap 1 2 Pac & Dr Dre Pac's Life *PO Clean Edit* 3:38 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2006 2Pac F. T.I. & Ashanti When I'm Gone 4:20 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3:58 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Bailen (Reggaeton) 3:41 Tropical Latin September 2002 3-2 Get Funky No More 3:48 Top 40 v. 24 3LW Feelin' You 3:35 Promo Only Rhythm Radio July 2006 3LW f./Jermaine Dupri El Baile Melao (Fast Cumbia) 3:23 Promo Only - Tropical Latin - December … 4 En 1 Until You Loved Me (Valentin Remix) 3:56 Promo Only: Rhythm Radio - 2005/06 4 Strings Until You Love Me 3:08 Rhythm Radio 2005-01 4 Strings Ain't Too Proud to Beg 2:36 M2 4 Tops Disco Inferno (Clean Version) 3:38 Disco Inferno - Single 50 Cent Window Shopper (PO Clean Edit) 3:11 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2005 50 Cent Window Shopper -

Instrumental Song Gospel Song Mariachi Song Vocal Duo Bilingual Song Mark Ipiotis Award

NMHMA Hispano Music Awards Nominees-2016 . SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Instrumental El Zopilote Mojado Mario Romero Gunshot Los Serranos Y Familia Song Polka Melodia Grupo Melodia of The Year Polka Zapatos Gony, Barbara & The Boyz Valse De Mis Padres The Dave Maestas Band SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Gospel Desde Que Dios Amanece Marcelina Velasquez Mundo Malo Cuarenta Y Cinco Song No Hay Dios Como Tu Jerry Dean & Alex Garcia of the Year Pescador De Hombres Al Hurricane Jr. Te Vas Angel Mio Bobby Madrid & Christina Perea SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Mariachi Cielito Lindo Huasteco Mariachi Sonidos Del Monte Song El Jinete Antonio Reyna of The Year El Mundo Es Mio Eddie Y Vengancia Te Vas Angel Mio Christina Perea Y Bobby Madrid VOCAL DUO SONG TITLE Vocal Christina Perea & Anita Lopez Flor De Las Flores Darren Cordova & Matthew Martinez Dos Hombres Y Un Destino Duo Jerry Dean & Christian Sanchez Mi Padrecito of The Year Severo Martinez & Jenna Baila Conmigo Tanya Griego & Justin Anaya Regresa Muy Pronto A Mi SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Bilingual Before The Next Tear Drop Falls Andrew Gonzales En El Mistico Black Pearl Band NM Song I Need to Know-Aye Dimelo Latino Persuasion of The Year Please Don’t Go Chelsea Chavez Wasted Days & Wasted Nights Miguel Timoteo NOMINEE Mark Glenda Martinez/KDCE Radio Ipiotis Kevin Otero-KANW Radio Mariachi Mike/KDCE Radio Award Mike Baca/KFUN Radio Norberto Martinez/KXMT Radio NMHMA Hispano Music Awards Nominees-2016 . SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Conjunto Chiquito Pero Picoso Rhythm Divine Norteño La Mala Vida Latino Persuasion Song Ojitos Verdes Eddie Y Venganzia of The Year Que Te Faltaba Andrew Gonzales Soy Toda Tuya Tanya Griego SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Crossover Chile Verde Rock Lluvia Negra Band El Retrato Chris Arellano Song En El Mistico Black Pearl Band NM of The Year I Got Mexico Cuarenta Y Cinco Please Don’t Go Chelsea Chavez SONG TITLE ARTIST/GROUP Cumbia Doña Juana Dwayne Ortega Band El Regañado Cuarenta Y Cinco Song La Roncona Al Hurricane Jr. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Digest of Other White House

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Digest of Other White House Announcements December 31, 2019 The following list includes the President's public schedule and other items of general interest announced by the Office of the Press Secretary and not included elsewhere in this Compilation. January 1 In the afternoon, the President posted to his personal Twitter feed his congratulations to President Jair Messias Bolsonaro of Brazil on his Inauguration. In the evening, the President had a telephone conversation with Republican National Committee Chairwoman Ronna McDaniel. During the day, the President had a telephone conversation with President Abdelfattah Said Elsisi of Egypt to reaffirm Egypt-U.S. relations, including the shared goals of countering terrorism and increasing regional stability, and discuss the upcoming inauguration of the Cathedral of the Nativity and the al-Fatah al-Aleem Mosque in the New Administrative Capital and other efforts to advance religious freedom in Egypt. January 2 In the afternoon, in the Situation Room, the President and Vice President Michael R. Pence participated in a briefing on border security by Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen M. Nielsen for congressional leadership. January 3 In the afternoon, the President had separate telephone conversations with Anamika "Mika" Chand-Singh, wife of Newman, CA, police officer Cpl. Ronil Singh, who was killed during a traffic stop on December 26, 2018, Newman Police Chief Randy Richardson, and Stanislaus County, CA, Sheriff Adam Christianson to praise Officer Singh's service to his fellow citizens, offer his condolences, and commend law enforcement's rapid investigation, response, and apprehension of the suspect. -

The State of Science in the Trump Era Damage Done, Lessons Learned, and a Path to Progress

The State of Science in the Trump Era Damage Done, Lessons Learned, and a Path to Progress {c S CenteD rfor Science and Democracy at the Union of Concerned Scientists The State of Science in the Trump Era Damage Done, Lessons Learned, and a Path to Progress Jacob Carter Emily Berman Anita Desikan Charise Johnson Gretchen Goldman January 2019 © 2019 Union of Concerned Scientists All Rights Reserved Jacob Carter is a scientist in the Center for Science and Democ- racy at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Emily Berman is the investigative researcher in the Center. Anita Desikan is a research analyst in the Center. Charise Johnson is a former research analyst in the Center. Gretchen Goldman is the research director of the Center. The Union of Concerned Scientists puts rigorous, independent science to work to solve our planet’s most pressing problems. Joining with citizens across the country, we combine technical analysis and effective advocacy to create innovative, practical solutions for a healthy, safe, and sustainable future. The Center for Science and Democracy at UCS works to strengthen American democracy by advancing the essential role of science, evidence-based decision making, and constructive debate as a means to improve the health, security, and prosperity of all people. More information about UCS and the Center for Science and Democracy is available on the UCS website: www.ucsusa.org This report is available online (in PDF format) at www.ucsusa.org/ ScienceUnderTrump Designed by: Tyler Kemp-Benedict Cover photo: Audrey Eyring/UCS -

Albuquerque Museum Oral History Project Johnny J. Armijo November 26, 2002 This Interview Was Conducted As Part of a Project By

Albuquerque Museum Oral History Project Johnny J. Armijo November 26, 2002 This interview was conducted as part of a project by the Albuquerque Museum to document the lives of people living in various city neighborhoods. Keywords and topics: Thee Chekkers, the South Valley, the Bosque, growing up in the South Valley, Ernie Pyle Middle School, Jack Ayala, Jerry Pacheco, Alfred Romero, David Nuñez, Nick Luchetti, Randy Castillo, Horn Oil, Atrisco Land Grant, Conrad Hilton, alcoholism, DWI Planning Council, Don Lesman’s Music Box, living in Salt Lake City, gang activity in the South Valley, Chicanismo, Sidro Garcia, Tom Barsanti, The Czars, Jim Burgett, Sloopy and the Red Barons, Fuller Brush and Rainbow Vacuum, Al Hurricane, Bennie Sanchez, meeting James Brown, Transmission Magazine, Los Padillas Community Center programming STEVENSON: This is Glen Stevenson with Johnny J. Armijo, November 25? ARMIJO: Sixth STEVENSON: Sixth. At the Los Padillas Community Center, in the South Valley. ARMIJO: Two thousand two. STEVENSON: Thanks, Johnny. ARMIJO: That was okay? [Interview starts at 00:22] ARMIJO: Part of what we were talking about is—or that I was talking about—is that, uh, I’m going to take you back, back, back. My dad was in a band—several bands, actually—he played with the Don Lesman Band, and he was in the 44th Army Band with the National Guard, J.J. Armijo, Johnny Jeremy. Anyway, from him and his band—he was a sax [saxophone] player: alto, tenor, and what’s the other one? Clarinet. [papers being shuffled in background] Played a little bit of piano. -

1 Dr. Kelvin Droegemeier Director, Office of Science and Technology

Dr. Kelvin Droegemeier Director, Office of Science and Technology Policy Executive Office of the President of the United States Before the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology United States House of Representatives on “The President’s FY 2021 Budget Request for Research & Development” February 27, 2020 Chairwoman Johnson, Ranking Member Lucas, and Members of the Committee, it is a privilege to be here with you today to discuss the President’s Budget for science and technology (S&T) research and development (R&D) in Fiscal Year (FY) 2021. In his State of the Union Address, President Trump declared that “We are pioneers” who “look at tomorrow and see unlimited frontiers just waiting to be explored.” Hearing these words, I was reminded of the words written in 1945 by Vannevar Bush, President Roosevelt’s de-facto science advisor. Dr. Bush wrote: “The pioneer spirit is still vigorous within this nation. Science offers a largely unexplored hinterland for the pioneer who has the tools for his task. The rewards of such exploration both for the Nation and the individual are great.” Since Dr. Bush, the architect of America’s post-World War II research framework, wrote these words in his treatise, Science—The Endless Frontier, America has experienced nearly uninterrupted growth in combined public, private, academic, and nonprofit research and development investment. Our Nation has created educational and training pathways into STEM for hard working, creative, and entrepreneurial Americans from every zip code, and we’ve attracted the best and brightest from every country. We have built the best discovery and innovation engine in history on bedrock American values, such as free inquiry, competition, and inclusion. -

Science at Risk? out of the Lab and Into the Public Sphere Fall 2018

SOCI 314: Science at Risk? Out of the Lab and Into the Public Sphere Fall 2018 Course Meetings: Tuesday and Thursday, 1-2:15pm, HRZ 210 Course Instructor: Simranjit Khalsa, PhD Candidate Office hours: Tuesdays and Thursdays after class or by appointment Office: Lovett 402 Email: [email protected] Course Overview Many of us have a love/hate relationship with science. We partake of science on a daily basis, through commonplace items like refrigeration and iPods and commonplace tasks like going to the doctor and driving across a bridge. Yet scientists struggle for acceptance by the general public, facing charges that science is not relevant enough to daily concerns and that some scientific advances raise troubling ethical issues. There is controversy over whether there should be more or less public funding for science and how much authority science should have over other ways of knowing, such as religion, or even if there are “other ways of knowing.” The scientific enterprise and scientists themselves are under pressure, by charges that the scientific workforce (and university science, in particular) does not represent the general public in terms of gender or racial make-up. Scientists are under pressure to please corporate and political interests. And general science knowledge among the US public is lower than in most industrialized nations. In this course we will explore all of these issues and more as we ask what happens when science enters the public sphere and the public sphere enters science. This course must be inherently inter-disciplinary. Politicians, ethicists, theologians, and public policy experts all discuss issues related to science and society and we read some of these works, including history, religious studies, and natural science texts.