Downloads Onto Iphones Or As Print-On-Demand Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction: Borderlines: Contemporary Scottish Gothic

Notes Introduction: Borderlines: Contemporary Scottish Gothic 1. Caroline McCracken-Flesher, writing shortly before the latter film’s release, argues that it is, like the former, ‘still an outsider tale’; despite the emphasis on ‘Scottishness’ within these films, they could only emerge from outside Scotland. Caroline McCracken-Flesher (2012) The Doctor Dissected: A Cultural Autopsy of the Burke and Hare Murders (Oxford: Oxford University Press), p. 20. 2. Kirsty A. MacDonald (2009) ‘Scottish Gothic: Towards a Definition’, The Bottle Imp, 6, 1–2, p. 1. 3. Andrew Payne and Mark Lewis (1989) ‘The Ghost Dance: An Interview with Jacques Derrida’, Public, 2, 60–73, p. 61. 4. Nicholas Royle (2003) The Uncanny (Manchester: Manchester University Press), p. 12. 5. Allan Massie (1992) The Hanging Tree (London: Mandarin), p. 61. 6. See Luke Gibbons (2004) Gaelic Gothic: Race, Colonization, and Irish Culture (Galway: Arlen House), p. 20. As Coral Ann Howells argues in a discussion of Radcliffe, Mrs Kelly, Horsley-Curteis, Francis Lathom, and Jane Porter, Scott’s novels ‘were enthusiastically received by a reading public who had become accustomed by a long literary tradition to associate Scotland with mystery and adventure’. Coral Ann Howells (1978) Love, Mystery, and Misery: Feeling in Gothic Fiction (London: Athlone Press), p. 19. 7. Ann Radcliffe (1995) The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne, ed. Alison Milbank (Oxford: Oxford University Press), p. 3. 8. As James Watt notes, however, Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne remains a ‘derivative and virtually unnoticed experiment’, heavily indebted to Clara Reeves’s The Old English Baron. James Watt (1999) Contesting the Gothic: Fiction, Genre and Cultural Conflict, 1764–1832 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), p. -

08.2013 Edinburgh International Book Festival

08.2013 Edinburgh International Book Festival Celebrating 30 years Including: Baillie Gifford Children’s Programme for children and young adults Thanks to all our Sponsors and Supporters The Edinburgh International Book Festival is funded by Benefactors James and Morag Anderson Jane Attias Geoff and Mary Ball Lel and Robin Blair Richard and Catherine Burns Kate Gemmell Murray and Carol Grigor Fred and Ann Johnston Richard and Sara Kimberlin Title Sponsor of Schools and Children’s Alexander McCall Smith Programmes & the Main Theatre Media Partner Fiona Reith Lord Ross Richard and Heather Sneller Ian Tudhope and Lindy Patterson Claire and Mark Urquhart William Zachs and Martin Adam and all those who wish to remain anonymous Trusts The Barrack Charitable Trust The Binks Trust Booker Prize Foundation Major Sponsors and Supporters Carnegie Dunfermline Trust The John S Cohen Foundation The Craignish Trust The Crerar Hotels Trust The final version is the white background version and applies to situations where only the wordmark can be used. Cruden Foundation The Educational Institute of Scotland The MacRobert Trust Matthew Hodder Charitable Trust The Morton Charitable Trust SINCE Scottish New Park Educational Trust Mortgage Investment The Robertson Trust 11 Trust PLC Scottish International Education Trust 909 Over 100 years of astute investing 1 Tay Charitable Trust Programme Supporters Australia Council for the Arts British Centre for Literary Translation and the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Edinburgh Unesco City of Literature Goethe Institute Italian Cultural Insitute The New Zealand Book Council Sponsors and Supporters NORLA (Norwegian Literature Abroad) Publishing Scotland Scottish Poetry Library South Africa’s Department of Arts and Culture Word Alliance With thanks The Edinburgh International Book Festival is sited in Charlotte Square Gardens by kind permission of the Charlotte Square Proprietors. -

Meet Author Alan Bissett Sporting Achievements the Stirling Fund

2012 alumni, staff and friends Meet author alan Bissett The 2011 Glenfiddich SpiriT of ScoTland wriTer of The year sporting achieveMents our STirlinG SporTS ScholarS the stirling Fund we Say Thank you 8 12 16 4 NEWS HIGHLIGHTS Successes and key developments 8 ALAN BISSETT Putting words on paper and on screen 12 HAZEL IRVINE An Olympic career 14 SPORT at STIRLING contents Thirty years of success 16 RESEARCH ROUND UP Stirling's contribution 38 18 MEET THE PRINCIPAL An interview with Professor Gerry McCormac 20 THE LOST GENERatiON? Graduate employment prospects 22 GOING WILD IN THE ARCHIVES Exhibition on campus 22 24 A CELEBRatiON OF cOLOUR AND SPRING Book launches at the University 25 THE STIRLING FUND Donations and developments 29 29 ADOPT A BOOK Support our campaign 31 CLASS NOTES 43 Find your friends 37 A WORD FROM THE PRESIDENT Your chance to get involved 38 MAKING THEIR MARK Graduates tell their story 43 WHERE ARE THEY NOW? Senior concierges in the halls 45 EVENTS FOR YOUR DIARY Let us entertain you 2 / stirling minds / Alumni, staff and Friends reasons to keep 10 in touch With over 44,000 Stirling alumni in 151 countries around the world there welcome are many reasons why you should keep in touch: Welcome to the 2012 edition of Stirling Minds which provides a glimpse into what has been an exciting 1. Maintain lifelong friendships. year for the University – from the presentation of 2. Network. Connection with the new Strategic Plan in the Scottish Parliament last alumni in similar fields, September to the ranking in a new THE (under 50 positions and locations. -

Alan Bissett

Alan Bissett Agent: Jonathan Kinnersley ([email protected]) Alan is a Scottish writer for screen, stage and page (the latter represented by AM Heath). Alan’s one man show (MORE) MOIRA MONOLOGUES won a Fringe First at the Edinburgh Festival in 2017 and was nominated for ‘Best New Play’ at the Critics’ Awards for Theatre in Scotland. It’s a sequel to THE MOIRA MONOLOGUES, which enjoyed two sold-out Edinburgh Fringe runs, numerous tours and whose lead character was declared ‘The most charismatic character to appear on a Scottish stage in a decade’ ★★★★ (Scotsman). Reviews: ★★★★★ – The Scotsman ★★★★ – The List ★★★★★ – Broadway Baby ★★★★★ – The National Scot ★★★★ – Edinburgh Spotlight In 2016 Alan’s play ONE THINKS OF IT ALL AS A DREAM toured Scotland, having been commissioned by the Scottish Mental Health Arts and Film Festival. It’s an ‘insightful eulogy’ (The Guardian) for the former Pink Floyd frontman, Syd Barrett: ★★★★ - ‘a lovingly and intensively researched play’ –The Herald ★★★★– ‘impressive, perfectly-judged’ – The Scotsman ‘a gem…beautifully honed and truly evocative mini-drama’ – The Sunday Herald Alan’s first play, THE CHING ROOM, a co-production between Glasgow’s Oran Mor and Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh, ran at both theatres in March 2009 to great critical acclaim. It since been revived at Glasgow’s Citizens Theatre, the Royal Exchange, Manchester and in Philadelphia. Alan also collaborated with The Moira Monologues’ director Sacha Kyle on TURBO FOLK (Oran Mor) which was nominated for Best New Play at the 2010 Critics’ Awards for Theatre in Scotland, and BAN THIS FILTH! which was shortlisted for an Amnesty International Freedom of Expression Award in 2013. -

The Poetry of Civic Nationalism: Jackie Kay's 'Bronze Head from Ife'

Article How to Cite: McFarlane, A 2017 The Poetry of Civic Nationalism: Jackie Kay’s ‘Bronze Head From Ife’. C21 Literature: Journal of 21st-century Writings, 5(2): 5, pp. 1–18, DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/c21.23 Published: 10 March 2017 Peer Review: This article has been peer reviewed through the double-blind process of C21 Literature: Journal of 21st-century Writings, which is a journal of the Open Library of Humanities. Copyright: © 2017 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distri- bution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: C21 Literature: Journal of 21st-century Writings is a peer-reviewed open access journal. Digital Preservation: The Open Library of Humanities and all its journals are digitally preserved in the CLOCKSS scholarly archive service. The Open Library of Humanities is an open access non-profit publisher of scholarly articles and monographs. Anna McFarlane, ‘The Poetry of Civic Nationalism: Jackie Kay’s ‘Bronze Head From Ife’’ (2017) 5(2): 5 C21 Literature: Journal of 21st-century Writings, DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/c21.23 ARTICLE The Poetry of Civic Nationalism: Jackie Kay’s ‘Bronze Head From Ife’ Anna McFarlane University of Glasgow, GB [email protected] This article examines the work of the newly-minted Scots makar, Jackie Kay, charting her development as a black Scottish writer committed to the interrogation of identity categories. -

1966-Pages.Pdf

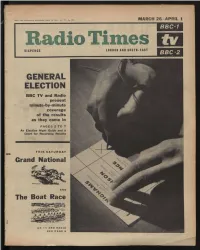

THE GENERAL On Thursday night and Friday morning the BBC both in Television and Radio will be giving you the fastest possible service of Election Results. Here David Butler, one of the expert commentators on tv, explains the background to the broadcasts TELEVISION A Guide for Election Night AND RADIO 1: Terms the commentators use 2: The swing and what it means COVERAGE THERE are 630 constituencies in the United Kingdom in votes and more than 1,600 candidates. The number of seats won by a major is fairly BBC-1 will its one- party begin compre- DEPOSIT Any candidate who fails to secure exactly related to the proportion of the vote which hensive service of results on eighth (12.5%), of the valid votes in his constituency it wins. If the number of seats won by Liberals and soon after of L150. Thursday evening forfeits to the Exchequer a deposit minor parties does not change substantially the close. the polls STRAIGHT FIGHT This term is used when only following table should give a fair guide of how the At the centre of operations two candidates are standing in a constituency. 1966 Parliament will differ from the 1964 Parlia- in the Election studio at ment. (In 1964 Labour won 44.1% of vote and huge MARGINAL SEATS There is no precise definition the TV Centre in London will be 317 seats; Conservatives won 43.4 % of the vote and of a marginal seat. It is a seat where there was a Cliff Michelmore keeping you 304 seats; Liberals 11.2% of the vote and nine seats small majority at the last election or a seat that in touch with all that is �a Labour majority over all of going is to change hands. -

4 Modern Shakespeare Festivals

UNIVERSIDAD DE MURCIA ESCUELA INTERNACIONAL DE DOCTORADO Festival Shakespeare: Celebrating the Plays on the Stage Festival Shakespeare: Celebrando las Obras en la Escena Dª Isabel Guerrero Llorente 2017 Page intentionally left blank. 2 Agradecimientos / Acknoledgements / Remerciments Estas páginas han sido escritas en lugares muy diversos: la sala becarios en la Universidad de Murcia, la British Library de Londres, el centro de investigación IRLC en Montpellier, los archivos de la National Library of Scotland, la Maison Jean Vilar de Aviñón, la biblioteca del Graduate Center de la City University of New York –justo al pie del Empire State–, mi habitación en Torre Pacheco en casa de mis padres, habitaciones que compartí con Luis en Madrid, Londres y Murcia, trenes con destinos varios, hoteles en Canadá, cafeterías en Harlem, algún retazo corregido en un avión y salas de espera. Ellas son la causa y el fruto de múltiples idas y venidas durante cuatro años, ayudándome a aunar las que son mis tres grandes pasiones: viajar, el estudio y el teatro.1 Si bien los lugares han sido esenciales para definir lo que aquí se recoge, aún más primordial han sido mis compañeros en este viaje, a los que hoy, por fin, toca darles las gracias. Mis primeras gracias son para mi directora de tesis, Clara Calvo. Gracias, Clara, por la confianza depositada en mí estos años. Gracias por propulsar tantos viajes intelectuales. Gracias también a Ángel-Luis Pujante y Vicente Cervera, quienes leyeron una versión preliminar de algunos capítulos y cuyos consejos han sido fundamentales para su mejora. Juanfra Cerdá fue uno de los primeros lectores de la propuesta primigenia y consejero excepcional en todo este proceso. -

The World, in Words News Release

THE WORLD, IN WORDS CHARLOTTE SQUARE GARDENS NEWS RELEASE EDINBURGH www.edbookfest.co.uk 11 – 27 AUGUST 2012 Sunday 12 th August 2012 FOR IMMEDIATE USE SCOTLAND NEEDS TO STOP BEING AFRAID OF ‘GETTING IT WRONG’ SAYS CAROL CRAIG Scotland needs to stop being afraid of ‘getting it wrong’ and increase its confidence if it is to move forward as a nation, argued Carol Craig, author of The Scots Crisis of Confidence, at the Edinburgh International Book Festival today. Speaking to a sold-out crowd on the second day of the Festival, Craig called upon her fellow Scots to radically rethink their nation’s psyche, particularly in the climate of independence. The author said that “there was something about Scottish beliefs and values that have an impact on people who live in the country”, commenting that immigrants were not changing Scottish culture but rather, “we change them, they don’t change us”. Comparing Scotland to America, Craig noted a distinct difference between the two country’s attitudes to success and equality, “In the US there is a notion that we are all equal, whereas in Scotland it is more that we are not of equal worth, but equally worthless.” The author, who is also the Chief Executive of The Centre for Confidence and Well-Being based in Glasgow, has rewritten her book, factoring in the SNP victory of 2007 which began a “palpable increase in collective confidence.” Craig suggested that by moving away from the critical culture which has become common-place in Scotland, the country would be better placed to move forward. -

EVENTS SECTION ONE 149.Indd

.V1$ .VR5 :GV``V1R.Q:R5 Q`JQ1:75CVQ`V115 VC7 %QG1CV7 VC7 %QG7 I:1C71J`Q Q`JQ1:7R@1]8HQ8%@ 1118IHC:%$.C1J]C:J 8HQ8%@ 1118 Q`JQ1:7@1]8HQ8%@ 22 Francis Street Stornoway •#%& ' Insurance Services R & G RMk Isle of Lewis Jewellery HS1 2NB •#'&( ) Risk Management &'()#'* t: 01851 704949 #* +# ,( ADVICE • Health & Safety YOU CAN ( )) www.rmkgroup.co.uk TRUST Zany's Summer Zone * +(,-../0/1 Section Four The local one stop solution for all your printing and design needs. S S 01851 700924 [email protected] Eilidh to www.sign-print.co.uk @signprintsty Church House, James St. Stornoway !7ryyShq premier &"%#% Gaelic song $ ! " # $ at HebCelt %&'& $ ())' 2 " See Section Four Page D9 "' "' ' +4 BANGLA SPICE Eilidh Mackenzie &'("' )* , ! - $' '+ $" !"# ./)#! ,-.0$1 0)12)30+454 6 7 8 8 8hyy # # # # # # # ! \ !" GhCyvr " $"$ % #$!% '$ & '%$ S G !"#$"%& %'$ #$% % &\ ' Zany's Ury) '$ &$( (Ah) '$ &#&#" !)*+ Summer Zone ! Section Four EVENTS SECTION ONE - Page 2 www.hebevents.com 05/07/18 - 01/08/18 Providing a lifeline of Mile of Pennies challenge for befrienders welfare and support to efriending Lewis, a local organisation Befriending Lewis currently support about Bworking to tackle loneliness and sixty one-to-one befriending relationships and fishermen and their social isolation in our community, will be have another dozen matches currently being attempting to build a MILE OF PENNIES this established. Over 100 people are supported families month! through the group befriending programme which offers monthly activities such as Fish’n The group invites you to come along to Chips lunches, activity/games/craft sessions, Tesco in Stornoway on Saturday 14th July to minibus trips around the island, music and help them achieve this. -

Reality 1–26 October, 2013

FILM THEATRE MUSIC COMEDY LITERATURE VISUAL ARTS WORKSHOPS AND MORE REALITY 1–26 OCTOBER, 2013 MHFESTIVAL.COM 2 / Partners The Scottish Mental Health Arts and Film Festival is hosted by the Mental Health Foundation in association with national partners If you would like to know more about the designers behind this year’s brochure, visit ostreet.co.uk Contents / 3 WELCOME TO THE 2013 FESTIVAL This October is all about reality. What does reality mean to you? Does anyone else see the world exactly as you do? Why do so many artists find mental health to be such a fertile ground for creativity? Launching in the Highlands, this year’s Festival will explore all these questions and more. Our line-up is our biggest and best yet, encompassing nearly 300 events stretching the length and breadth of Scotland. Our exhilarating film programme will challenge you to see life through a different lens; while theatre invites you to enter new worlds through live performance. We have a brand new collaboration in the shape of a weekend literature festival with Aye Write! And, as always, our festival is rooted in the creativity of communities throughout Scotland, with a backbone of workshops, exhibitions and celebrations from those working to promote positive mental health and challenge stigma all year round. Thanks to our fantastic network of artists, activists and organisers, we are now one of the largest social justice festivals in the world. Join us and be moved, amused, provoked and inspired. And help us create new realities and possibilities. Lee Knifton -

Contemporary Poetry in Scots

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository 1 Roderick Watson Living with the double tongue: contemporary poetry in Scots The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature, Volume Three: Modern Transformations: New Identities (from 1918) Edinburgh University Press, 2006, pp. 163-175. At the beginning of the 20th century literary renaissance one of the main drivers of Scottish writing was the socio-political need to establish cultural difference from what was perceived as an English tradition— to make room for one’s own, so to speak. In this regard Hugh MacDiarmid’s propaganda for the use of Scots to counter the hegemony of standard English has been of immense importance to 20th century Scottish writing –even for those writers such as Tom Leonard and James Kelman who would disagree with his political nationalism. More than that, MacDiarmid’s case was a seminal one in the development of all literatures in English, and his essay on ‘English Ascendancy in British Literature’, first published in Eliot’s The Criterion in July 1931, is a key —if often neglected— document in the early history of postcolonial studies. Nor would Kelman and Leonard be out of sympathy with the case it makes for difference, plurality and so-called ‘marginal’ utterance. By the 1930s MacDiarmid’s claims for a tri-lingual Scotland were well established and the case for linguistic and cultural pluralism has been upheld with increasing sophistication ever since. The use of a plural title for the magazine Scotlands in 1994 is a case in point, as is the slowly growing recognition since then that ‘Scottish’ literature might even be written in languages other than English, Gaelic or Scots as it is, for example, in the polyglot Urdu / Glaswegian demotic in Suhayl Saadi’s 2004 novel Psychoraag. -

32Nd All Scotland Results 2016

32nd All Scotland Championships o Competition Name Under 6 Mixed Competition N 1 OVERALL RESULT Date 18-21 Feb 2016 Competitor Position Total Marks Competitor Name School Location Number 1 300.00 16 Avelene Mulligan Doherty-Petri Belfast, Ireland & New York USA 2 210.00 4 Doireann Moffatt Sylvan Kelly Co Mayo, Ireland 3 200.00 19 Evie Georgina Roberts Duffy-Travis North West Region, England 4 176.50 17 Garet Zagorski Southern Southern Region, USA 5 170.00 7 Aoibheann Doherty Deery Derry, Ireland 6 151.00 15 Tabitha Sherlock Kelly Hendry North East Region, England 7 145.00 9 Kristina Dawson Kidd-Cieslak Denny, Scotland 8 142.00 12 Aine Gaynor Claddagh Essex & London, England 9 140.50 10 Alex O'Donnell Sarah McGowan Derry, Ireland 10 135.00 6 Megan Mallen Kelly Hendry North East Region, England 11 128.00 1 Leah Dorrian Domican Donegal, Ireland 12 118.00 18 Molly Young Kilkenny The Hague, Netherlands 13 116.00 3 Elizabeth Campbell Maguire-O'Shea London, England 14 113.00 8 Fayth Flynn Manning Southern Region, England 15 107.50 11 Luke McMorrow Maguire-O'Shea London, England 16 105.50 2 Mia Lambden Feely-Bates Kildare & Dublin, Ireland 17 104.00 14 Dylan Frederick Aaron Crosbie Southern Region, England 32nd All Scotland Championships o Competition Name Under 7 Mixed Competition N 2 OVERALL RESULT Date 18-21 Feb 2016 Competitor Position Total Marks Competitor Name School Location Number 1 260.00 36 Isabella Zibe Kelly Hendry North East Region, England 2 250.00 32 Khloe McConomy Bradley McConomy-Bradley Ulster, Ireland 3 205.00 35 Kyra Himawan