Articles from Theosophy — April 1896 to October 1897 Editors: E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Early Days of Theosophy in Europe by A.P

The Early Days of Theosophy in Europe by A.P. Sinnett The Early Days of Theosphy in Europe by A.P. Sinnett Theosophical Publishing House Ltd, London, 1922 NOTE [Page 5] Mr. Sinnett's literary Executor in arranging for the publication this volume is prompted to add a few words of explanation. There is naturally some diffidence experienced in placing before the public a posthumous MSS of personal reminiscences dealing in various instances with people still living. It would, however, be impossible to use the editorial blue pencil without destroying the historical value of the MSS. Mr. Sinnett's position and associations with the Theosophical Society together with his standing as an author in the Theosophical movement alike demand that his last writing should be published, and it is left to each reader to form his own judgment as to the value of the book in the light of his own study of the questions involved. Page 1 The Early Days of Theosophy in Europe by A.P. Sinnett CHAPTER - 1 - NO record could truly be called a History of the Theosophical Society if it concerned itself merely with events taking shape on the physical plane of life. From the first such events have been the result of activities on a higher plane; of steps taken by the unseen Powers presiding over human evolution, whose existence was unknown in the outer world when their great undertaking — the Theosophical Movement — was originally set on foot. To those known in the outer world as the Founders of the Theosophical Society — Madame Blavatsky and Colonel Olcott — the existence of these higher powers, The Brothers as they were called at first, was more or less imperfectly comprehended. -

Three Eminent Theosophists

Three Eminent Theosophists Three Eminent Theosophists v. 10.21, www.philaletheians.co.uk, 30 May 2021 Page 1 of 13 THEOSOPHY AND THEOSOPHISTS SERIES Three Eminent Theosophists 1 by Boris de Zirkoff 2 Archibald Keightley 1859–1930 3 Julia Wharton Keightley 1851–1915 8 Bertram Keightley 1860–1944 11 1 Title page illustration by James White, NeoWave Series 3. 2 [Boris Mihailovich de Zirkoff (Борис́ Михайлович́ Цирков́ ), 1902–1981, Russian-born American Theosophist, editor, and writer. He was born in Saint Petersburg, Russia, March 7th 1902. His father was Mihail Vassilyevich de Zirkoff, a Russian general; his mother, Lydia Dmitriyevna von Hahn, who was a second cousin to Helena Pe- trovna Blavatsky. The Russian Revolution forced his family to flee in 1917 to Stockholm across Finland. De Zirkoff studied in European universities, where he specialized in languages and classics. “At Baden-Baden in Germany, he met a Russian American, Nikolai Romanoff, and learned from him about the existence, at Point Loma, close San Diego in California, of the organization, named Universal Brotherhood and Theosophical Socie- ty. He wrote a letter to Mrs. Katherine Tingley, then head of the Society, and when she visited Europe, they met in Finland. Mrs. Tingley, who had learned that Boris was Blavatsky's relative, invited him to come to the head- quarters at Point Loma and promised him all the necessary help in regard to his travel to America.” — Anton Rozman. Also consult “De Zirkoff recalls his formative years in Russia,” in the same Series. — ED. PHIL.] Three Eminent Theosophists v. 10.21, www.philaletheians.co.uk, 30 May 2021 Page 2 of 13 THEOSOPHY AND THEOSOPHISTS SERIES ARCHIBALD KEIGHTLEY 1859–1930 From Blavatsky Collected Writings, (BIBLIOGRAPHY) IX pp. -

2020-11-21 Lecture Johanna Vermeulen HOW HPB TEACHES

H.P. Blavatsky H.P. Blavatsky The Secret Doctrine Commentaries The Unpublished 1889 Instructions Te Secret Doctrine Commentaries Te Unpublished 1889 Instructions TRANSCRIBED AND ANNOTATED BY MICHAEL GOMES Unique book to discover how HPB applied Raja Yoga Education principles: a.the educator invites the reincarnating ego outward, teaching him to bring his personality under his own inner discipline. b. the educator stimulates the own sense of responsibility of the pupil c. the educator stimulates the pupil to actively strenghten and ennoble his character (= transform all kama-manasic thinking (passions and egotistic tendencies) into buddhi-manasisch thinking (wisdom and idealism) d. the educator stimulates compassion: self-forgetfulness and living for others e. the educator stimulates a harmonious, well-balanced development: inner equilibrium in all situations 1884 H.P. Blavatsky from India to Europe 1884-6 H.P. Blavatsky works on The Secret Doctrine 1884 H.P. Blavatsky from India to Europe 1884-6 H.P. Blavatsky works on The Secret Doctrine 1887 (May 1) invited to London to finish The Secret Doctrine 1887 (May 19) starts Blavatsky Lodge 1887 starts Lucifer, the Lightbringer 1884 H.P. Blavatsky from India to Europe 1884-6 H.P. Blavatsky works on The Secret Doctrine 1887 (May 1) invited to London to finish The Secret Doctrine 1887 (May 19) starts Blavatsky Lodge 1887 starts Lucifer, the Lightbringer 1888 Volume 1 of The Secret Doctrine published 1888 starts Esoteric School (Esoteric Instructions) 1884 H.P. Blavatsky from India to Europe 1884-6 H.P. Blavatsky works on The Secret Doctrine 1887 (May 1) invited to London to finish The Secret Doctrine 1887 (May 19) starts Blavatsky Lodge 1887 starts Lucifer, the Lightbringer 1888 Volume 1 of The Secret Doctrine published 1888 starts Esoteric School (Esoteric Instructions) 1889 Blavatsky Lodge studies Stanza’s of Dzyan in SD 1 1889 The Key to Theosophy published 1889 The Voice of the Silence published 1890-1 Transactions of the Blavatsky Lodge published Study SD I Stanzas Jan - Jun 1889: 22 meetings Frederic L. -

The Real "H.P.B."

THE REAL "H.P.B." “We employ agents – the best available. Of these for the past thirty years the chief has been the personality known as H.P.B. to the world (but otherwise to us). Imperfect and very troublesome, no doubt, she proves to some, nevertheless, there is no likelihood of our finding a better one… – and your theosophists should be made to understand it. … Theosophists should learn it. You will understand later the significance of this declaration so keep it in mind. Her fidelity to our work being constant, and her sufferings having come upon her thro’ it, neither I nor either of my Brother associates will desert or supplant her. As I once before remarked, ingratitude is not among our vices.” - Master K.H. “About a month after I joined the Society I felt as it were a voice within myself whispering to me that Madam Blavatsky is not what she represents herself to be. It then assumed the form of a belief in me which grew so strong within a short time that four or five times I thought of throwing myself at her feet and beg her to reveal herself to me. But then I could not do so because I thought it would be useless, as I knew that I was quite impure and had led too bad a life to be trusted with that secret. I therefore remained silent with the consolation that she herself would confide the secret to me when she would find me worthy of it. I thought it must be some great Indian Adept that had assumed that illusionary form. -

The Theosophist

THE THEOSOPHIST VOL. 134 NO. 7 APRIL 2013 CONTENTS On the Watch-Tower 3 Radha Burnier Make Theosophy a Living Power 6 N. Sri Ram The Past, Present and the Future 7 Manju Sundaram Confirmation of the Existence of an Ancient Worldwide Wisdom Religion 14 Ray Walder and Edi Bilimoria The Making of The Secret Doctrine 20 Michael Gomes Time — Some Reflections 30 D. P. Sabnis How Can Ancient Wisdom Heal the Earth? 34 Kusum Galada Theosophical Work around the World 36 International Directory 40 Editor: Mrs Radha Burnier NOTE: Articles for publication in The Theosophist should be sent to the Editorial Office. Cover: An evening sky in Adyar — J. Suresh Official organ of the President, founded by H. P. Blavatsky, 1879. The Theosophical Society is responsible only for official notices appearing in this magazine. 1 THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY Founded 17 November 1875 President: Mrs Radha Burnier Vice-President: Mr M. P. Singhal Secretary: Mrs Kusum Satapathy Treasurer: Mr T. S. Jambunathan Headquarters: ADYAR, CHENNAI (MADRAS) 600 020, INDIA Secretary: [email protected] Treasury: [email protected] Adyar Library and Research Centre: [email protected] Theosophical Publishing House: [email protected] & [email protected] Fax: (+91-44) 2490-1399 Editorial Office: [email protected] Website: http://www.ts-adyar.org The Theosophical Society is composed of students, belonging to any religion in the world or to none, who are united by their approval of the Society’s Objects, by their wish to remove religious antagonisms and to draw together men of goodwill, whatsoever their religious opinions, and by their desire to study religious truths and to share the results of their studies with others. -

The University of Sydney Copyright in Relation to This Thesis·

The University of Sydney Copyright in relation to this thesis· Under the Copyright Act 1968 (several provision of which are referred to below), this thesis must be used only under the normal conditions of scholarly fair dealing for the purposes of research, criticism or review. In particular no results or conclusions should be extracted from it. nor should it be copied or closely paraphrased in whole or in part without the written consent of the author. Proper written acknowledgement should be made for any assistance obtained from this thesis. Under Section 35(2) of the Copyright Act 1968 'the author of a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is the owner of any copyright subsisting in the work'. By virtue of Section 32( I) copyright 'subsists in an original literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work that is unpublished' and of which the author was an Australian citizen, an Australian protected person or a person reSident in Australia. The Act. by Section 36( I) provides: 'Subject to this Act. the copyright in a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is mfringed by a person who, not being the owner of the copyright and without the licence of the owner of the copyright, does in Australia. or authorises the doing in Australia of, any act comprised in the copyright'. Section 31 (I )(a)(i) provides that copyright includes the exclusive right to 'reproduce the work in a material form'.Thus, copyright IS mfringed by a person who, not being the owner of the copyright. reproduces or authorises the reproduction of a work. -

The Key to Theosophy by H. P. Blavatsky

Theosophical University Press Online Edition THE KEY TO THEOSOPHY BY H. P. BLAVATSKY Being a Clear Exposition, in the Form of Question and Answer, of the ETHICS, SCIENCE, AND PHILOSOPHY for the Study of which The Theosophical Society has been Founded. Originally published 1889. Theosophical University Press electronic version ISBN 1- 55700-046-8 (print version also available). Due to current limitations in the ASCII character set, and for ease of searching, no diacritical marks appear in this electronic version of the text. Dedicated by "H. P. B." To all her Pupils that They may Learn and Teach in their turn. CONTENTS PREFACE SECTION 1: THEOSOPHY AND THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY (28K) ● The Meaning of the Name ● The Policy of the Theosophical Society ● The Wisdom-Religion Esoteric in all Ages ● Theosophy is not Buddhism SECTION 2: EXOTERIC AND ESOTERIC THEOSOPHY (44K) ● What the Modern Theosophical Society is not ● Theosophists and Members of the "T. S." ● The Difference between Theosophy and Occultism ● The Difference between Theosophy and Spiritualism ● Why is Theosophy accepted? SECTION 3: THE WORKING SYSTEM OF THE T. S. (22K) ● The Objects of the Society ● The Common Origin of Man ● Our other Objects ● On the Sacredness of the Pledge SECTION 4: THE RELATIONS OF THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY TO THEOSOPHY (15K) ● On Self-Improvement ● The Abstract and the Concrete SECTION 5: THE FUNDAMENTAL TEACHINGS OF THEOSOPHY (39K) ● On God and Prayer ● Is it Necessary to Pray? ● Prayer Kills Self-Reliance ● On the Source of the Human Soul ● The Buddhist -

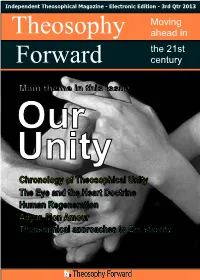

Theosophy Moving Forward

Independent Theosophical Magazine Electronic Edition 3rd Qtr 2013 Moving Theosophy ahead in the 21st Forward century Main theme in this issue Our Unity Chronology of Theosophical Unity The Eye and the Heart Doctrine Human Regeneration Adyar, Mon Amour Theosophical approaches to Christianity Theosophy Forward This independent electronic magazine offers a portal to Theosophy for all those who believe that its teachings are timeless. It shuns passing fads, negativity, and the petty squabbles of sectarianism that mar even some efforts to propagate the eternal Truth. Theosophy Forward offers a positive and constructive outlook on current affairs. Theosophy Forward encourages all Theosophists, of whatever organizations, as well as those who are unaligned but carry Theosophy in their hearts, to come together. Theosophists of any allegiance can meet and respectfully exchange views, because each of us is a centre for Theosophical work. It needs to be underscored that strong ties are maintained with all the existing Theosophical Societies, but the magazine's commitment lies with Theosophy only and not with individuals or groups representing these various vehicles. Theosophy Forward 4th Quarter 2013 Regular Edition of Theosophy Forward Front cover photo by David Grossman Published by Theosophy Forward Produced by the Rman Institute Copyright © Theosophy Forward 2013 Contents Page THEOSOPHY 6 Chelas and Lay Chelas by H. P. Blavatsky 7 Our Unity by Dorothy Bell 15 Our Unity by John Algeo 19 Our Unity The Aura of AllBeing by Nicholas -

KATALOG 18 Versandantiquariat Hans-Jürgen Lange Lerchenkamp 7A D-29323 Wietze

KATALOG 18 Versandantiquariat Hans-Jürgen Lange Lerchenkamp 7a D-29323 Wietze Tel.: 05146-986038 Email: [email protected] Bestellungen werden streng nach Eingang bearbeitet. Versandkosten (u. AGB) siehe letzte Katalogseite. Alchemie u. Alte Rosenkreuzer 1-35 Astrologie 36-74 Freimaurer u.a. Geheimbünde 75-102 Germanische Mythologie u. Vorgeschichte 103-130 Grenzwissenschaften 131-171 Heilkunde u. Ernährung 172-209 Lebensreform u. völkische Bewegungen 210-239 Okkultismus u. Magie 240-293 Runen u. Sinnbilder 294-317 Spiritismus u. Parapsychologie 318-357 Theosophie u. Anthroposophie 358-419 Utopie u. Phantastik 420-491 Volkskunde, Aberglaube u. Zauberei 492-525 Varia 526-666 Weitere Angebote - sowie PDF-Download dieses Katalogs (mit Farbabbildungen) - unter www.antiquariatlange.de . Wir sind stets am Ankauf antiquarischer Bücher aller Gebiete der Grenz - und Geheimwissenschaft en interessiert! Alchemie und Alte Rosenkreuzer 1. Andreä, Johann Valentin und Ferdinand Dr. Maack (Hrsg.): Die Johann Valentin Andreä zugeschriebenen vier Hauptschriften der alten Rosenkreuzer. 1. Chymische Hochzeit: Christiani Rosencreutz. 2. Allgemeine Reformation der gantzen Welt. 3. Fama Fraternitatis. 4. Confessio Fraternitatis. Mit einer allgemeinen und speziellen Einleitung herausgegeben von Dr. med. Ferdinand Maack. Mit Porträt Andreaes und Abbildungen. 1. Aufl. Berlin, Hermann Barsdorf Verlag, 1913. 5 Bll., LIV, 115, 84 S., mit Frontispiz, einer Taf. u. Textabb., 8°, Blaues illus. O-Leinen 128,00 € (= Geheime Wissenschaften. Eine Sammlung seltener älterer und neuerer Schriften über Alchemie, Magie, Kabbalah, Rosenkreuzerei, Freimaurerei, Hexen- und Teufelswesen usw. Unter Mitwirkung namhafter Autoren herausgegeben von A. v. d. Linden. Erster Band). - Ackermann V/17. - (1) Chymische Hochzeit: Christiani Rosencreutz. Anno 1459. Nach der zu Straßburg bei Lazari Zetners seel. Erben im Jahre 1616 erschienenen Ausgabe neugedruckt. -

The Theosophical Movement

THE THEOSOPHICAL MOVEMENT 1875 -1950 THE CUNNINGHAM PRESS Los ANGELES 32, CALIFORNIA COPYRIGHT, 1951 BY THE CUNNINGHAM PRESS All Rights Reserved PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA e-copy courtesy of http://www.phx-ult-lodge.org/theosophica%20lmovement.htm page numbers are at the top of the page “Night before last I was shown a bird’s eye view of the theosophical societies. I saw a few earnest reliable theosophists in a death struggle with the world in general and with other— nominal and ambitious theosophists. The former are greater in number than you may think, and they prevailed—as you in America will prevail, if you only remain staunch to the Master’s programme and true to yourselves.” —H. P. B., 1888 PREFACE IN 1925, just fifty years after the founding of the Theosophical Society in New York, the first accurate and thorough history of the Theosophical Movement was published by E. P. Dutton and Company. This volume, entitled The Theosophical Movement, 1875-1925, a History and a Survey, was com piled by the editors of Theosophy, a monthly journal devoted to the original objects of the Theosophical Movement. It provided theosophical students and others interested in the subject with a detailed and documented study of the lifework of H. P. Blavatsky and other leading figures of the Theosophical Movement. Encompassed in the 700 pages of the book were careful accounts of all the major events of Theosophical history, with enough evidence assembled for every reader to form his own conclusions regarding matters of controversy; or at least, sufficient to place serious inquirers well along on the path of individual investigation. -

Volume 4, Issue 5 September—October 2020

The Journal of CESNUR $ Volume 4, Issue 5 September—October 2020 $ The Journal of CESNUR $ Director-in-Charge | Direttore responsabile Marco Respinti Editor-in-Chief | Direttore Massimo Introvigne Center for Studies on New Religions, Turin, Italy Associate Editor | Vicedirettore PierLuigi Zoccatelli Pontifical Salesian University, Turin, Italy Editorial Board / International Consultants Milda Ališauskienė Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania Eileen Barker London School of Economics, London, United Kingdom Luigi Berzano University of Turin, Turin, Italy Antoine Faivre École Pratique des Hautes Études, Paris, France Holly Folk Western Washington University, Bellingham, Washington, USA Liselotte Frisk Dalarna University, Falun, Sweden J. Gordon Melton Baylor University, Waco, Texas, USA Susan Palmer McGill University, Montreal, Canada Stefania Palmisano University of Turin, Turin, Italy Bernadette Rigal-Cellard Université Bordeaux Montaigne, Bordeaux, France Instructions for Authors and submission guidelines can be found on our website at www.cesnur.net. ISSN: 2532-2990 The Journal of CESNUR is published bi-monthly by CESNUR (Center for Studies on New Religions), Via Confienza 19, 10121 Torino, Italy. $ The Journal of CESNUR $ Volume 4, Issue 5, September—October 2020 Contents Articles 3 A Brief History of the Theosophical Society in Japan in the Interwar Period Helena Čapková 27 A New Religion Fights for Peace: The Case of the Quakers in Korea J. Gordon Melton 42 Esotericism in the Mirror of COVID-19: Gregorian Bivolaru, MISA, and the Pandemic Massimo Introvigne 64 Abusus Non Tollit Usum? Korea’s Legal Response to Coronavirus and the Shincheonji Church of Jesus Ciarán Burke 86 COVID-19: Treatment of Clusters in Protestant Churches and the Shincheonji Church in South Korea. -

KATALOG 3 Versandantiquariat Hans-Jürgen Lange Lerchenkamp

KATALOG 3 Versandantiquariat Hans-Jürgen Lange Lerchenkamp 7a D-29323 Wietze Tel.: 05146-986038 Email: [email protected] Bestellungen werden streng nach Eingang bearbeitet. Versandkosten siehe letzte Seite. Alchemie 1-10 Astrologie 11-73 Charakterkunde, Handlesen, Graphologie 74-110 Fraternitas Saturni 111-170 Fraternitas Saturni - empfohlene Literatur 171-213 Freimaurer u.a. Geheimbünde 214-261 Grenzwissenschaften 262-291 Heilkunde u. Ernährung 292-379 Hypnose, Suggestion u. Magnetismus 380-408 Okkultismus u. Magie 409-449 Philosophie u. Psychologie 450-490 Radiästhesie 491-546 Spiritismus u. Parapsychologie 547-591 Theosophie u. Anthroposophie 592-651 Utopie u. Phantastik 652-722 Varia 723-888 Weitere Angebote unter www.AntiquariatLange.de. Wir sind stets am Ankauf antiquarischer Bücher aller Gebiete der Grenz- und Geheimwissenschaften interessiert! Gedruckt in 400 nummerierten Exemplaren. Nr. 1-260 wurden handkoloriert und erhielten eine montierte Abbildung. ................. Alchemie 1. Aquino, Thomas von: Abhandlung über den Stein der Weisen. Übersetzt, herausgegeben und mit einer ausführlichen Einleitung versehen von Gustav Meyrink. 1. Aufl. Leipzig, Zürich, Wien u. München-Planegg, Otto Wilhelm Barth-Verlag, 1925. XLVII, 56 S., 8°, Illus. goldbedruckter O-Karton 50,00 € U.a. über: Abhandlung des Heiligen Thomas vom Orden der Dominikaner über den Stein der Weisen u. zunächst über die außerirdischen Körper; Über die niederen Körper u. die Natur u. die Eigenschaften der Mineralien. Zunächst über die Steine; Von der Beschaffenheit u. der Essenz der Metalle; Von der Essentiellen Substanz der Metalle; Von der Verwandlung der Metalle u. zunächst von der, die sich auf künstlichem Wege vollzieht; Von der Natur u. der Herstellung eines neuen Goldes u. eines neuen Silbers mit Hilfe des Schwefels, der aus dem mineralischen Gestein gewonnen wird; Vom natürlichen animalischen u.