Concrete: Art Design Architecture Education Resource Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

新成立/ 註冊及已更改名稱的公司名單list of Newly Incorporated

This is the text version of a report with Reference Number "RNC063" and entitled "List of Newly Incorporated /Registered Companies and Companies which have changed Names". The report was created on 31-08-2015 and covers a total of 2879 related records from 24-08-2015 to 30-08-2015. 這是報告編號為「RNC063」,名稱為「新成立 / 註冊及已更改名稱的公司名單」的純文字版報告。這份報告在 2015 年 8 月 31 日建立,包含從 2015 年 8 月 24 日到 2015 年 8 月 30 日到共 2879 個相關紀錄。 Each record in this report is presented in a single row with 6 data fields. Each data field is separated by a "Tab". The order of the 6 data fields are "Sequence Number", "Current Company Name in English", "Current Company Name in Chinese", "C.R. Number", "Date of Incorporation / Registration (D-M-Y)" and "Date of Change of Name (D-M-Y)". 每個紀錄會在報告內被設置成一行,每行細分為 6 個資料。 每個資料會被一個「Tab 符號」分開,6 個資料的次序為「順序編號」、「現用英文公司名稱」、「現用中文公司名稱」、「公司註冊編號」、「成立/註 冊日期(日-月-年)」、「更改名稱日期(日-月-年)」。 Below are the details of records in this report. 以下是這份報告的紀錄詳情。 1. (D & A) Development Limited 2280098 28-08-2015 2. 100 Business Limited 100 分顧問有限公司 2278033 24-08-2015 3. 13 GLOBAL GROUP LIMITED 壹三環球集團有限公司 2279402 26-08-2015 4. 262 Island Trading Group Limited 2278529 24-08-2015 5. 3 Mentors Limited 2278378 24-08-2015 6. 3a Network Limited 三俠網絡有限公司 2278169 24-08-2015 7. 3D Systems Hong Kong Co., Limited 1016514 26-08-2015 8. 716 Studio Company Limited 716 工作室有限公司 2280037 28-08-2015 9. 80 INNOVATE TECHNOLOGY LIMITED 百翎創新科技有限公司 2278139 24-08-2015 10. -

National Architecture Award Winners 1981 – 2019

NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARDS WINNERS 1981 - 2019 AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARD WINNERS 1 of 81 2019 NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARDS COLORBOND® Award for Steel Architecture Yagan Square (WA) The COLORBOND® Award for Steel Architecture Lyons in collaboration with Iredale Pedersen Hook and landscape architects ASPECT Studios COMMERCIAL ARCHITECTURE Dangrove (NSW) The Harry Seidler Award for Commercial Architecture Tzannes Paramount House Hotel (NSW) National Award for Commercial Architecture Breathe Architecture Private Women’s Club (VIC) National Award for Commercial Architecture Kerstin Thompson Architects EDUCATIONAL ARCHITECTURE Our Lady of the Assumption Catholic Primary School (NSW) The Daryl Jackson Award for Educational Architecture BVN Braemar College Stage 1, Middle School National Award for Educational Architecture Hayball Adelaide Botanic High School (SA) National Commendation for Educational Architecture Cox Architecture and DesignInc QUT Creative Industries Precinct 2 (QLD) National Commendation for Educational Architecture KIRK and HASSELL (Architects in Association) ENDURING ARCHITECTURE Sails in the Desert (NT) National Award for Enduring Architecture Cox Architecture HERITAGE Premier Mill Hotel (WA) The Lachlan Macquarie Award for Heritage Spaceagency architects Paramount House Hotel (NSW) National Award for Heritage Breathe Architecture Flinders Street Station Façade Strengthening & Conservation National Commendation for Heritage (VIC) Lovell Chen Sacred Heart Building Abbotsford Convent Foundation -

24 March 2020 Mr Tim Smith Director Operations Heritage NSW

Upper Fort Street, Observatory Hill Millers Point, NSW 2000 GPO BOX 518 Sydney NSW 2001 T +61 2 9258 0123 F +61 2 9251 1110 www.nationaltrust.org.au/NSW 24 March 2020 Mr Tim Smith Director Operations Heritage NSW Department of Premier and Cabinet Locked Bag 5020 PARRAMATTA NSW 2124 Email: [email protected] Dear Tim, Ultimo Power House – SHR Nomination The Exhibited Nomination Form I refer to the exhibited Nomination Form for the former Ultimo Power House that is proposed to be presented to the Heritage Council for consideration for inclusion on the NSW State Heritage Register. Although the nomination carries the National Trust’s name, in its current form it is very different to the nomination submitted by the National Trust in 2015. It appears to have been considerably re-worded since its receipt by Heritage NSW. The Ultimo Power House is clearly of State-level significance and should be included in the State Heritage Register (SHR), to give it the appropriate level of statutory oversight and protection. However, the National Trust is gravely concerned that, if the Power House were to be listed on the State Heritage Register for the reasons set out in the advertised nomination, then it would be listed for inadequate and poorly stated reasons (even if this were preferable to it not being listed at all). When the National Trust nominated the Ultimo Power House in 2015, we believed that the site involved larger heritage significance issues associated with its operation as part of the Powerhouse Museum. At the time, we had insufficient information to pursue that aspect of its significance. -

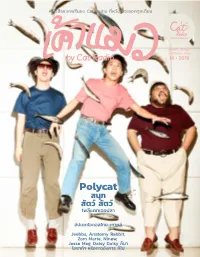

By Cat Radio 16 • 2019

หนังสือแจกฟรีของ Cat Radio ทีหวังว่าจะออกทุกเดือน่ แจกฟรี มีไม่เยอะ เก็บไว้เหอะ ...เมียว้ by Cat Radio 16 • 2019 Polycat สนุก สัตว์ สัตว์ โพลีแคทเจอปลา อัปเดตไอดอลไทย-เกาหลี Jeebbs, Anatomy Rabbit, Zom Marie, Ninew, Jesse Meg, Daisy1 Daisy ก็มา โอซาก้า หรือดาวอังคาร ก็ไป Undercover สืบจากปก by _punchspmngknlp คุณยาย บ.ก. ของเรา เสนอปกเล่มนี้ตอนทุกคนก�าลังยุ่งกับการ เตรียมงาน Cat Tshirt 6 แล้วอาศัยโอกาสลงมือท�าเลย จึงไม่มีโมเมนต์ การอภิปรายหรือเห็นชอบจากใคร อย่าได้ถามถึงความชอบธรรมใดๆ ว่า ท�าไมปกเค้าแมวกลับมาเป็นศิลปินชายอีกแล้ว (วะ) แต่ชีวิตไม่สิ้นก็ดิ้นกันไป เราได้เสนอปกรวมดาวไอดอลชุดแซนตี้ ช่วง คริสมาสต์ไปแล้ว เราสัญญาว่าเราจะไฟต์ ให้ก�าลังใจเราด้วย แต่ถ้าไม่ได้ก็ คือไม่ได้ จบ รักนะ (O,O) 2 3 เข้าช่วงท้ายของพุทธศักราช 2562 แล้ว เราจึงชวนวงดนตรีที่เพิ่งมีคอนเสิร์ตใหญ่ครั้งแรก 2 วงมาขึ้น ในฐานะผู้สังเกตการณ์ นับเป็นปีที่ ปกเค้าแมวฉบับเดียวกัน แม้จะต่างทั้งชั่วโมงบินในการท�างาน น่าชื่นใจของหลายศิลปินที่มีคอนเสิร์ต สไตล์ดนตรี สังกัด แต่เราคิดว่าทั้งคู่คงมีความสุขในการใช้เวลา ใหญ่/คอนเสิร์ตแรก ตลอดจนการไปเล่น ร่วมกับแฟนเพลงในคอนเสิร์ตเต็มรูปแบบของตนเอง รวมถึงการ CAT Intro ในเวที/เทศกาลดนตรีนานาชาติ หรือมี ท�าอะไรหลายอย่างที่น่าสนุกอย่างมาก พูดแบบกันเองก็สนุกสัสๆ RADIO ผลงานใดๆ ที่แฟนเพลงต่างสนับสนุน เราเลยจัดสัตว์มาถ่ายรูปขึ้นปกกับพวกเขาด้วยในคอนเซปต์ “สนุก อุดหนุน และภาคภูมิใจไปด้วย สัตว์ สัตว์” แต่อย่างที่เคยได้ยินกันว่าท�างานกับสัตว์ก็ไม่ง่าย ภาพ DJ Shift อาจเปรียบดังรางวัลหรือก�าลังใจ ที่ได้จึงมีทั้งสัตว์จริงและไม่จริง แต่กล่าวด้วยความสัตย์จริงว่าเรา จากการท�างานหนัก/ทุ่มเทให้สิ่งที่รัก สนุกกับการท�างานกับทั้งสองวง และหวังว่าบทสนทนาที่ปรากฏจะ -

Hijjas Kasturi and Harry Seidler in Malaysia

Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand 30, Open Papers presented to the 30th Annual Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand held on the Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia, July 2-5, 2013. http://www.griffith.edu.au/conference/sahanz-2013/ Amit Srivastava, “Hijjas Kasturi and Harry Seidler in Malaysia: Australian-Asian Exchange and the Genesis of a ‘Canonical Work’” in Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 30, Open, edited by Alexandra Brown and Andrew Leach (Gold Coast, Qld: SAHANZ, 2013), vol. 1, p 191-205. ISBN-10: 0-9876055-0-X ISBN-13: 978-0-9876055-0-4 Hijjas Kasturi and Harry Seidler in Malaysia Australian-Asian Exchange and the Genesis of a “Canonical Work” Amit Srivastava University of Adelaide In 1980, months after his unsuccessful competition entries for the Australian Parliament House and the Hong Kong Shanghai Bank headquarters, Harry Seidler entered into collaboration with Malaysian architect Hijjas (bin) Kasturi that proved much more fruitful. Their design for an office building for Laylian Realty in Kuala Lumpur was a departure from Seidler’s quadrant geometries of the previous decade, introducing a sinuous “S” profile that would define his subsequent work. Although never realised, Kenneth Frampton has described this project as a “canonical work” that was the “basic prototype for a new generation of medium to high-rise commercial structures.” But Seidler’s felicitous collaboration with Hijjas was evidently more than just circumstantial, arising from a longer term relationship that is part of a larger story of Australian-Asian exchange. -

Religion, Cultural Diversity and Safeguarding Australia

Cultural DiversityReligion, and Safeguarding Australia A Partnership under the Australian Government’s Living In Harmony initiative by Desmond Cahill, Gary Bouma, Hass Dellal and Michael Leahy DEPARTMENT OF IMMIGRATION AND MULTICULTURAL AND INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS and AUSTRALIAN MULTICULTURAL FOUNDATION in association with the WORLD CONFERENCE OF RELIGIONS FOR PEACE, RMIT UNIVERSITY and MONASH UNIVERSITY (c) Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2004 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth available from the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Intellectual Property Branch, Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts, GPO Box 2154, Canberra ACT 2601 or at http:www.dcita.gov.au The statement and views expressed in the personal profiles in this book are those of the profiled person and are not necessarily those of the Commonwealth, its employees officers and agents. Design and layout Done...ByFriday Printed by National Capital Printing ISBN: 0-9756064-0-9 Religion,Cultural Diversity andSafeguarding Australia 3 contents Chapter One Introduction . .6 Religion in a Globalising World . .6 Religion and Social Capital . .9 Aim and Objectives of the Project . 11 Project Strategy . 13 Chapter Two Historical Perspectives: Till World War II . 21 The Beginnings of Aboriginal Spirituality . 21 Initial Muslim Contact . 22 The Australian Foundations of Christianity . 23 The Catholic Church and Australian Fermentation . 26 The Nonconformist Presence in Australia . 28 The Lutherans in Australia . 30 The Orthodox Churches in Australia . -

Fiche 2003 Modern Movement

Harry and Penelope Seidler House, Killara Sydney, NSW Australia d o c o m o m o _ _ ! ! International working party for documentation and conservation New International Selection of buildings, sites and neighbourhoods of the Full Documentation Fiche 2003 modern movement for office use only composed by national/regional working party of: Australia 0. Picture of building/ group of buildings/ urban scheme/ landscape/ garden depicted item: Harry and Penelope Seidler House source: Harry Seidler & associates web site http://www.seidler.net.au depicted item: Harry and Penelope Seidler House source: Harry Seidler & associates web site http://www.seidler.net.au d o ! c o _ m o ! m o _ International working party for ISC/R members update 2003 documentation and conservation of buildings, sites and neighbourhoods of the for office use only modern movement 1 of 10 Harry and Penelope Seidler House, Killara Sydney, NSW Australia 1. Identity of building/ group of buildings/ group of buildings/ landscape/ garden 1.1 Data for identification current name: HARRY AND PENELOPE SEIDLER HOUSE former/original/variant name: Harry and Penelope Seidler House number(s) and name(s) of street(s): 13 Kalang Avenue town: Killara, Sydney province/state: NSW post code: 2071 block: lot: country: Australia national topographical grid reference: current typology: Residence former/original/variant typology: Residence comments on typology: 1.2 Status of protection protected by: state/province/town/record only Proposed for listing on the State Heritage Register by the RAIA www.heritage.nsw.gov.ay -

08.14 | the Burg | 1 Community Publishers

08.14 | The Burg | 1 Community Publishers As members of Harrisburg’s business community, we are proud to support TheBurg, a free publication dedicated to telling the stories of the people of greater Harrisburg. Whether you love TheBurg for its distinctive design, its in-depth reporting or its thoughtful features about the businesses and residents who call our area home, you know the value of having responsible, community-centered coverage. We’re thrilled to help provide greater Harrisburg with the local publication it deserves. Realty Associates, Inc. Wendell Hoover ray davis 2 | The Burg | 08.14 CoNTeNTS |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| General and leTTers NeWS 2601 N. FroNT ST., SuITe 101 • hArrISBurg, PA 17101 WWW.TheBurgNeWS.CoM 7. NEWS DIGEST ediTorial: 717.695.2576 9. cHucklE Bur G ad SALES: 717.695.2621 10. cITy vIEW 12. state strEET PuBLISher: J. ALeX hArTZLer [email protected] COVER arT By: KrisTin KesT eDITor-IN-ChIeF: LAWrANCe BINDA IN The Burg www.KesTillUsTraTion.CoM [email protected] "The old Farmer's Almanac 2015 garden 14. from THE GrouND up Calendar, yankee Publishing Co." SALeS DIreCTor: LAureN MILLS 22. mIlestoNES [email protected] leTTer FroM THe ediTor SeNIor WrITer: PAuL BArker [email protected] “Nobody on the road/Nobody on the beach” BuSINess AccouNT eXeCuTIve: ANDreA Black More than once, I’ve thought of those lyrics [email protected] 26. fAcE of Business from Don henley’s 30-year-old song, “Boys 28. SHop WINDoW of Summer,” after a stroll down 2nd Street ConTriBUTors: or along the riverfront on a hot August day. It seems that everyone has left for TArA Leo AuChey, Today’S The day hArrISBurg the summer—to the shore, the mountains, [email protected] abroad. -

METRON T2M MM Title4 MM Title5 Sydney Metro Southwest Metro Design Services (SMDS)

METRON T2M MM_Title4 MM_Title5 Sydney Metro Southwest Metro Design Services (SMDS) METRON T2M Punchbowl Station Design & Precinct Plan Sydney Metro Southwest Metro Design Services (SMDS) 09 March 2021 Document: SMCSWSWM-MTM-WPS-UD-REP-241000 A Joint Venture of Principal sub-consultant METRON is a joint venture of Arcadis and Mott MacDonald, with principal sub-consultant DesignInc METRON is a joint venture of Arcadis and Mott MacDonald, with principal sub-consultant Design Inc. Sydney Metro Southwest Metro Design Services (SMDS) Approval Record Amendment Record Function Position Name Date Date Document Number/s Revision Amendment Description By Prepared by Senior Urban Designer & Ben Coulston & Remy Miles 08 March 2021 21 May 2020 SMCSWSWM-MTM-WPS-UD-REP-241000 A 100% Draft Ben Coulston with input Urban Designer from UD and LA team Technical Checker Principal Urban Designer Lynne Hancock 08 March 2021 28 July 2020 SMCSWSWM-MTM-WPS-UD-REP-241000 B 100% Draft Ben Coulston with input from UD and LA team Reviewed by T2M Urban Design Lead Mary Anne McGirr 08 March 2021 09 March 2021 SMCSWSWM-MTM-WPS-UD-REP-241000 C 100% Final Ben Coulston with input Approved by Director Ian Armstrong 08 March 2021 from UD and LA team Punchbowl Station Design & Precinct Plan. Document: SMCSWSWM-MTM-WPS-UD-REP-241000 Sydney Metro Southwest Metro Design Services (SMDS) Contents 1.0 Introduction 1 4.0 Design 35 5.0 Transport and Access 63 1.1 Project description 1 4.1 Project design 35 5.1 Transport and access design measures 63 1.2 Purpose and scope 3 4.2 Station -

North Shore Houses Project

NORTH SHORE HOUSES, State Library of New South Wales Generously supported by the Upper North Architects Network (SPUN), Australian Institute of Architects. Compiled by John Johnson Arranged alphabetically by architect. Augustus Aley Allen & Jack Architects (Russell Jack) Allen, Jack & Cottier (Russell Jack) Sydney Ancher Adrian Ashton Arthur Baldwinson Arthur Baldwinson (Baldwinson & Booth) John Brogan Hugh Buhrich Neville Gruzman Albert Hanson Edward Jeaffreson Jackson Richard Leplastrier Gerard McDonnell D.T. Morrow and Gordon Glen Murcutt Nixon & Adam (John Shedden Adam) Pettit, Sevitt & Partners Exhibition Houses Ross Brothers (Herbert Ernest Ross and Colin John Ross) Ernest A Scott (Green & Scott) Harry Seidler Harry and Penelope Seidler Douglas Snelling John Sulman War Service Homes Commission Leslie Wilkinson Wilson & Neave (William Hardy Wilson) Architect: Augustus Aley ‘Villa Maria’ (House for Augustus Aley), 1920 8 Yosefa Avenue, Warrawee Architect Augustus Aley (1883-1968) built 4 houses in Yosefa Avenue, Warrawee (Nos. 7, 8, 9, 11) two of which were constructed for himself. He and wife Beatrice (1885?-1978) moved into Villa Maria in 1920 and developed a fine garden. In 1929 they moved to a new house, Santos, at 11 Yosefa Ave. “Mr Aley, the architect, and incidentally the owner, has planned both house and garden with the utmost care, so that each should combine to make a delightful whole. The irregular shape and sloping nature of the ground presented many difficulties, but at the same time abounded with possibilities, of which he has taken full advantage. The most important thing, in a house of this sort, and indeed in any house, is aspect, and here it is just right. -

Marmalade at the Jam Factory

Marmalade at the Jam Factory Droylsden A collection of 2, 3 and 4 bedroom homes ‘ A reputation built on solid foundations Bellway has been building exceptional quality new homes throughout the UK for over 75 years, creating outstanding properties in desirable locations. During this time, Bellway has earned a strong Our high standards are reflected in our dedication to reputation for high standards of design, build customer service and we believe that the process of quality and customer service. From the location of buying and owning a Bellway home is a pleasurable the site, to the design of the home, to the materials and straightforward one. Having the knowledge, selected, we ensure that our impeccable attention support and advice from a committed Bellway team to detail is at the forefront of our build process. member will ensure your home-buying experience is seamless and rewarding, at every step of the way. We create developments which foster strong communities and integrate seamlessly with Bellway abides by The the local area. Each year, Bellway commits Consumer Code, which is to supporting education initiatives, providing an independent industry transport and highways improvements, code developed to make healthcare facilities and preserving - as well as the home buying process creating - open spaces for everyone to enjoy. fairer and more transparent for purchasers. Over 75 years of housebuilding expertise and innovation distilled into our flagship range of new homes. Artisan traditions sit at the heart of Bellway, who refreshed and improved internal specification for more than 75 years have been constructing carefully marries design with practicality, homes and building communities. -

“Knowing Is Seeing”: the Digital Audio Workstation and the Visualization of Sound

“KNOWING IS SEEING”: THE DIGITAL AUDIO WORKSTATION AND THE VISUALIZATION OF SOUND IAN MACCHIUSI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO September 2017 © Ian Macchiusi, 2017 ii Abstract The computer’s visual representation of sound has revolutionized the creation of music through the interface of the Digital Audio Workstation software (DAW). With the rise of DAW- based composition in popular music styles, many artists’ sole experience of musical creation is through the computer screen. I assert that the particular sonic visualizations of the DAW propagate certain assumptions about music, influencing aesthetics and adding new visually- based parameters to the creative process. I believe many of these new parameters are greatly indebted to the visual structures, interactional dictates and standardizations (such as the office metaphor depicted by operating systems such as Apple’s OS and Microsoft’s Windows) of the Graphical User Interface (GUI). Whether manipulating text, video or audio, a user’s interaction with the GUI is usually structured in the same manner—clicking on windows, icons and menus with a mouse-driven cursor. Focussing on the dialogs from the Reddit communities of Making hip-hop and EDM production, DAW user manuals, as well as interface design guidebooks, this dissertation will address the ways these visualizations and methods of working affect the workflow, composition style and musical conceptions of DAW-based producers. iii Dedication To Ba, Dadas and Mary, for all your love and support. iv Table of Contents Abstract ..................................................................................................................