Field Effect Transistors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quantum Well Devices: Applications of the PIAB

Quantum Well Devices: Applications of the PIAB. H2A Real World Friday What is a semiconductor? no e- Conduction Band Empty e levels a few e- Empty e levels lots of e- Empty e levels Filled e levels Filled e levels Filled e levels Insulator Semiconductor Metal Electrons in the conduction band of semiconductors like Si or GaAs can move about freely. Conduction band a few e- Eg = hν Energy Bandgap in Valence band Filled e levels Semiconductors We can get electrons into the conduction band by either thermal excitation or light excitation (photons). Solar cells use semiconductors to convert photons to electrons. A "quantum well" structure made from AlGaAs-GaAs-AlGaAs creates a potential well for conduction electrons. 10-20 nm! A conduction electron that get trapped in a quantum well acts like a PIAB. A conduction electron that get trapped in a quantum well acts like a PIAB. Quantum Wells are used to make Laser Diodes Quantum Well Laser Diodes Quantum Wells are used to make Laser Diodes Quantum Well Laser Diodes Multiple Quantum Wells work even better. Multiple Quantum Well Laser Diodes Multiple Quantum Wells work even better. Multiple Quantum Well LEDs Multiple Quantum Wells work even better. Multiple Quantum Well Laser Diodes Multiple Quantum Wells also are used to make high efficiency Solar Cells. Quantum Well Solar Cells Multiple Quantum Wells also are used to make high efficiency Solar Cells. The most common approach to high efficiency photovoltaic power conversion is to partition the solar spectrum into separate bands and each absorbed by a cell specially tailored for that spectral band. -

Fundamentals of Nanoelectronics (Fone)

ESF EUROCORES Programme Fundamentals of NanoElectronics (FoNE) Highlights European Science Foundation (ESF) Physical and Engineering Sciences (PESC) The European Science Foundation (ESF) is an The Physical and Engineering Sciences are key drivers independent, non-governmental organisation, the for research and innovation, providing fundamental members of which are 78 national funding agencies, insights and creating new applications for mankind. research performing agencies, academies and learned The goal of the ESF Standing Committee for Physical societies from 30 countries. and Engineering Sciences (PESC) is to become the The strength of ESF lies in its influential membership pan-European platform for innovative research and and in its ability to bring together the different domains competitive new ideas while addressing societal of European science in order to meet the challenges of issues in a more effective and sustainable manner. the future. The Committee is a unique cross-disciplinary Since its establishment in 1974, ESF, which has its group, with networking activities comprising a good headquarters in Strasbourg with offices in Brussels mix of experimental and theoretical approaches. and Ostend, has assembled a host of organisations It distinguishes itself by focusing on fundamental that span all disciplines of science, to create a research and engineering. PESC covers the following common platform for cross-border cooperation in broad spectrum of fields: chemistry, mathematics, Europe. informatics and the computer sciences, physics, ESF is dedicated to promoting collaboration in fundamental engineering sciences and materials scientific research, funding of research and science sciences. policy across Europe. Through its activities and instruments ESF has made major contributions to science in a global context. -

Dephasing in an Electronic Mach-Zehnder Interferometer,” Phys

Dephasing and Quantum Noise in an electronic Mach-Zehnder Interferometer Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) der Fakultät für Physik der Universität Regensburg vorgelegt von Andreas Helzel aus Kelheim Dezember 2012 ii Promotionsgesuch eingereicht am: 22.11.2012 Die Arbeit wurde angeleitet von: Prof. Dr. Christoph Strunk Prüfungsausschuss: Prof. Dr. G. Bali (Vorsitzender) Prof. Dr. Ch. Strunk (1. Gutachter) Dr. F. Pierre (2. Gutachter) Prof. Dr. F. Gießibl (weiterer Prüfer) iii In Gedenken an Maria Höpfl. Sie war die erste Taxifahrerin von Kelheim und wurde 100 Jahre alt. Contents 1. Introduction1 2. Basics 5 2.1. The two dimensional electron gas....................5 2.2. The quantum Hall effect - Quantized Landau levels...........8 2.3. Transport in the quantum Hall regime.................. 10 2.3.1. Quantum Hall edge states and Landauer-Büttiker formalism.. 10 2.3.2. Compressible and incompressible strips............. 14 2.3.3. Luttinger liquid in the QH regime at filling factor 2....... 16 2.4. Non-equilibrium fluctuations of a QPC.................. 24 2.5. Aharonov-Bohm Interferometry..................... 28 2.6. The electronic Mach-Zehnder interferometer............... 30 3. Measurement techniques 37 3.1. Cryostat and devices........................... 37 3.2. Measurement approach.......................... 39 4. Sample fabrication and characterization 43 4.1. Fabrication................................ 43 4.1.1. Material.............................. 43 4.1.2. Lithography............................ 44 4.1.3. Gold air bridges.......................... 45 4.1.4. Sample Design.......................... 46 4.2. Characterization.............................. 47 4.2.1. Filling factor........................... 47 4.2.2. Quantum point contacts..................... 49 4.2.3. Gate setting............................ 50 5. Characteristics of a MZI 51 5.1. -

Notes for Lab 1 (Bipolar (Junction) Transistor Lab)

ECE 327: Electronic Devices and Circuits Laboratory I Notes for Lab 1 (Bipolar (Junction) Transistor Lab) 1. Introduce bipolar junction transistors • “Transistor man” (from The Art of Electronics (2nd edition) by Horowitz and Hill) – Transistors are not “switches” – Base–emitter diode current sets collector–emitter resistance – Transistors are “dynamic resistors” (i.e., “transfer resistor”) – Act like closed switch in “saturation” mode – Act like open switch in “cutoff” mode – Act like current amplifier in “active” mode • Active-mode BJT model – Collector resistance is dynamically set so that collector current is β times base current – β is assumed to be very high (β ≈ 100–200 in this laboratory) – Under most conditions, base current is negligible, so collector and emitter current are equal – β ≈ hfe ≈ hFE – Good designs only depend on β being large – The active-mode model: ∗ Assumptions: · Must have vEC > 0.2 V (otherwise, in saturation) · Must have very low input impedance compared to βRE ∗ Consequences: · iB ≈ 0 · vE = vB ± 0.7 V · iC ≈ iE – Typically, use base and emitter voltages to find emitter current. Finish analysis by setting collector current equal to emitter current. • Symbols – Arrow represents base–emitter diode (i.e., emitter always has arrow) – npn transistor: Base–emitter diode is “not pointing in” – pnp transistor: Emitter–base diode “points in proudly” – See part pin-outs for easy wiring key • “Common” configurations: hold one terminal constant, vary a second, and use the third as output – common-collector ties collector -

Engineered Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene for Nanoelectronics And

Engineered Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene for Nanoelectronics and Nanomechanics E. H. Yang Stevens Institute of Technology, Castle Point on Hudson, Hoboken, NJ, USA, 07030 ABSTRACT We are exploring nanoelectronic engineering areas based on low dimensional materials, including carbon nanotubes and graphene. Our primary research focus is investigating carbon nanotube and graphene architectures for field emission applications, energy harvesting and sensing. In a second effort, we are developing a high-throughput desktop nanolithography process. Lastly, we are studying nanomechanical actuators and associated nanoscale measurement techniques for re-configurable arrayed nanostructures with applications in antennas, remote detectors, and biomedical nanorobots. The devices we fabricate, assemble, manipulate, and characterize potentially have a wide range of applications including those that emerge as sensors, detectors, system-on-a-chip, system-in-a-package, programmable logic controls, energy storage systems, and all-electronic systems. INTRODUCTION A key attribute of modern warfare is the use of advanced electronics and information technologies. The ability to process, analyze, distribute and act upon information from sensors and other data at very high- speeds has given the US military unparalleled technological superiority and agility in the battlefield. While recent advances in materials and processing methods have led to the development of faster processors and high-speed devices, it is anticipated that future technological breakthroughs in these areas will increasingly be driven by advances in nanoelectronics. A vital enabler in generating significant improvements in nanoelectronics is graphene, a recently discovered nanoelectronic material. The outstanding electrical properties of both carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [1] and graphene [2] make them exceptional candidates for the development of novel electronic devices. -

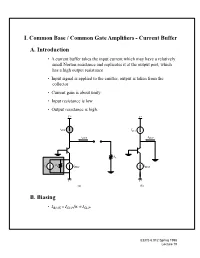

I. Common Base / Common Gate Amplifiers

I. Common Base / Common Gate Amplifiers - Current Buffer A. Introduction • A current buffer takes the input current which may have a relatively small Norton resistance and replicates it at the output port, which has a high output resistance • Input signal is applied to the emitter, output is taken from the collector • Current gain is about unity • Input resistance is low • Output resistance is high. V+ V+ i SUP ISUP iOUT IOUT RL R is S IBIAS IBIAS V− V− (a) (b) B. Biasing = /α ≈ • IBIAS ISUP ISUP EECS 6.012 Spring 1998 Lecture 19 II. Small Signal Two Port Parameters A. Common Base Current Gain Ai • Small-signal circuit; apply test current and measure the short circuit output current ib iout + = β v r gmv oib r − o ve roc it • Analysis -- see Chapter 8, pp. 507-509. • Result: –β ---------------o ≅ Ai = β – 1 1 + o • Intuition: iout = ic = (- ie- ib ) = -it - ib and ib is small EECS 6.012 Spring 1998 Lecture 19 B. Common Base Input Resistance Ri • Apply test current, with load resistor RL present at the output + v r gmv r − o roc RL + vt i − t • See pages 509-510 and note that the transconductance generator dominates which yields 1 Ri = ------ gm µ • A typical transconductance is around 4 mS, with IC = 100 A • Typical input resistance is 250 Ω -- very small, as desired for a current amplifier • Ri can be designed arbitrarily small, at the price of current (power dissipation) EECS 6.012 Spring 1998 Lecture 19 C. Common-Base Output Resistance Ro • Apply test current with source resistance of input current source in place • Note roc as is in parallel with rest of circuit g v m ro + vt it r − oc − v r RS + • Analysis is on pp. -

Precision Current Sources and Sinks Using Voltage References

Application Report SNOAA46–June 2020 Precision Current Sources and Sinks Using Voltage References Marcoo Zamora ABSTRACT Current sources and sinks are common circuits for many applications such as LED drivers and sensor biasing. Popular current references like the LM134 and REF200 are designed to make this choice easier by requiring minimal external components to cover a broad range of applications. However, sometimes the requirements of the project may demand a little more than what these devices can provide or set constraints that make them inconvenient to implement. For these cases, with a voltage reference like the TL431 and a few external components, one can create a simple current bias with high performance that is flexible to fit meet the application requirements. Current sources and sinks have been covered extensively in other Texas Instruments application notes such as SBOA046 and SLYC147, but this application note will cover other common current sources that haven't been previously discussed. Contents 1 Precision Voltage References.............................................................................................. 1 2 Current Sink with Voltage References .................................................................................... 2 3 Current Source with Voltage References................................................................................. 4 4 References ................................................................................................................... 6 List of Figures 1 Current -

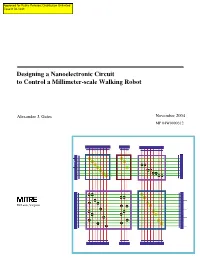

Designing a Nanoelectronic Circuit to Control a Millimeter-Scale Walking Robot

Designing a Nanoelectronic Circuit to Control a Millimeter-scale Walking Robot Alexander J. Gates November 2004 MP 04W0000312 McLean, Virginia Designing a Nanoelectronic Circuit to Control a Millimeter-scale Walking Robot Alexander J. Gates November 2004 MP 04W0000312 MITRE Nanosystems Group e-mail: [email protected] WWW: http://www.mitre.org/tech/nanotech Sponsor MITRE MSR Program Project No. 51MSR89G Dept. W809 Approved for public release; distribution unlimited. Copyright © 2004 by The MITRE Corporation. All rights reserved. Gates, Alexander Abstract A novel nanoelectronic digital logic circuit was designed to control a millimeter-scale walking robot using a nanowire circuit architecture. This nanoelectronic circuit has a number of benefits, including extremely small size and relatively low power consumption. These make it ideal for controlling microelectromechnical systems (MEMS), such as a millirobot. Simulations were performed using a SPICE circuit simulator, and unique device models were constructed in this research to assess the function and integrity of the nanoelectronic circuit’s output. It was determined that the output signals predicted for the nanocircuit by these simulations meet the requirements of the design, although there was a minor signal stability issue. A proposal is made to ameliorate this potential problem. Based on this proposal and the results of the simulations, the nanoelectronic circuit designed in this research could be used to begin to address the broader issue of further miniaturizing circuit-micromachine systems. i Gates, Alexander I. Introduction The purpose of this paper is to describe the novel nanoelectronic digital logic circuit shown in Figure 1, which has been designed by this author to control a millimeter-scale walking robot. -

Lecture 12 Digital Circuits (II) MOS INVERTER CIRCUITS

Lecture 12 Digital Circuits (II) MOS INVERTER CIRCUITS Outline • NMOS inverter with resistor pull-up –The inverter • NMOS inverter with current-source pull-up • Complementary MOS (CMOS) inverter • Static analysis of CMOS inverter Reading Assignment: Howe and Sodini; Chapter 5, Section 5.4 6.012 Spring 2007 Lecture 12 1 1. NMOS inverter with resistor pull-up: Dynamics •CL pull-down limited by current through transistor – [shall study this issue in detail with CMOS] •CL pull-up limited by resistor (tPLH ≈ RCL) • Pull-up slowest VDD VDD R R VOUT: VOUT: HI LO LO HI V : VIN: IN C LO HI CL HI LO L pull-down pull-up 6.012 Spring 2007 Lecture 12 2 1. NMOS inverter with resistor pull-up: Inverter design issues Noise margins ↑⇒|Av| ↑⇒ •R ↑⇒|RCL| ↑⇒ slow switching •gm ↑⇒|W| ↑⇒ big transistor – (slow switching at input) Trade-off between speed and noise margin. During pull-up we need: • High current for fast switching • But also high incremental resistance for high noise margin. ⇒ use current source as pull-up 6.012 Spring 2007 Lecture 12 3 2. NMOS inverter with current-source pull-up I—V characteristics of current source: iSUP + 1 ISUP r i oc vSUP SUP _ vSUP Equivalent circuit models : iSUP + ISUP r r vSUP oc oc _ large-signal model small-signal model • High current throughout voltage range vSUP > 0 •iSUP = 0 for vSUP ≤ 0 •iSUP = ISUP + vSUP/ roc for vSUP > 0 • High small-signal resistance roc. 6.012 Spring 2007 Lecture 12 4 NMOS inverter with current-source pull-up Static Characteristics VDD iSUP VOUT VIN CL Inverter characteristics : iD = V 4 3 VIN VGS I + DD SUP roc 2 1 = vOUT vDS VDD (a) VOUT 1 2 3 4 VIN (b) High roc ⇒ high noise margins 6.012 Spring 2007 Lecture 12 5 PMOS as current-source pull-up I—V characteristics of PMOS: + S + VSG _ VSD G B − _ + IDp 5 V + D − V + G − V − D − ID(VSG,VSD) (a) = VSG 3.5 V 300 V = V + V = V − 1 V 250 (triode SD SG Tp SG region) V = 3 V 200 SG − IDp (µA) (saturation region) 150 = VSG 25 100 = 0, 0.5, VSG 1 V (cutoff region) V = 2 V 50 SG = VSG 1.5 V 12345 VSD (V) (b) Note: enhancement-mode PMOS has VTp <0. -

Chapter 10 Differential Amplifiers

Chapter 10 Differential Amplifiers 10.1 General Considerations 10.2 Bipolar Differential Pair 10.3 MOS Differential Pair 10.4 Cascode Differential Amplifiers 10.5 Common-Mode Rejection 10.6 Differential Pair with Active Load 1 Audio Amplifier Example An audio amplifier is constructed as above that takes a rectified AC voltage as its supply and amplifies an audio signal from a microphone. CH 10 Differential Amplifiers 2 “Humming” Noise in Audio Amplifier Example However, VCC contains a ripple from rectification that leaks to the output and is perceived as a “humming” noise by the user. CH 10 Differential Amplifiers 3 Supply Ripple Rejection vX Avvin vr vY vr vX vY Avvin Since both node X and Y contain the same ripple, their difference will be free of ripple. CH 10 Differential Amplifiers 4 Ripple-Free Differential Output Since the signal is taken as a difference between two nodes, an amplifier that senses differential signals is needed. CH 10 Differential Amplifiers 5 Common Inputs to Differential Amplifier vX Avvin vr vY Avvin vr vX vY 0 Signals cannot be applied in phase to the inputs of a differential amplifier, since the outputs will also be in phase, producing zero differential output. CH 10 Differential Amplifiers 6 Differential Inputs to Differential Amplifier vX Avvin vr vY Avvin vr vX vY 2Avvin When the inputs are applied differentially, the outputs are 180° out of phase; enhancing each other when sensed differentially. CH 10 Differential Amplifiers 7 Differential Signals A pair of differential signals can be generated, among other ways, by a transformer. -

Transistor Current Source

PY 452 Advanced Physics Laboratory Hans Hallen Electronics Labs One electronics project should be completed. If you do not know what an op-amp is, do either lab 2 or lab 3. A written report is due, and should include a discussion of the circuit with inserted equations and plots as appropriate to substantiate the words and show that the measurements were taken. The report should not consist of the numbered items below and short answers, but should be one coherent discussion that addresses most of the issues brought out in the numbered items below. This is not an electronics course. Familiarity with electronics concepts such as input and output impedance, noise sources and where they matter, etc. are important in the lab AND SHOULD APPEAR IN THE REPORT. The objective of this exercise is to gain familiarity with these concepts. Electronics Lab #1 Transistor Current Source Task: Build and test a transistor current source, , +V with your choice of current (but don't exceed the transistor, power supply, or R ratings). R1 Rload You may wish to try more than one current. (1) Explain your choice of R1, R2, and Rsense. VCE (a) In particular, use the 0.6 V drop of VBE - rule for current flow to calculate I in R2 VBE Rsense terms of Rsense, and the Ic/Ib rule to estimate Ib hence the values of R1&R2. (2) Try your source over a wide range of Rload values, plot Iload vs. Rload and interpret. You may find it instructive to look at VBE and VCE with a floating (neither side grounded) multimeter. -

Current Source & Source Transformation Notes

EE301 – CURRENT SOURCES / SOURCE CONVERSION Learning Objectives a. Analyze a circuit consisting of a current source, voltage source and resistors b. Convert a current source and a resister into an equivalent circuit consisting of a voltage source and a resistor c. Evaluate a circuit that contains several current sources in parallel Ideal sources An ideal source is an active element that provides a specified voltage or current that is completely independent of other circuit elements. DC Voltage DC Current Source Source Constant Current Sources The voltage across the current source (Vs) is dependent on how other components are connected to it. Additionally, the current source voltage polarity does not have to follow the current source’s arrow! 1 Example: Determine VS in the circuit shown below. Solution: 2 Example: Determine VS in the circuit shown above, but with R2 replaced by a 6 k resistor. Solution: 1 8/31/2016 EE301 – CURRENT SOURCES / SOURCE CONVERSION 3 Example: Determine I1 and I2 in the circuit shown below. Solution: 4 Example: Determine I1 and VS in the circuit shown below. Solution: Practical voltage sources A real or practical source supplies its rated voltage when its terminals are not connected to a load (open- circuited) but its voltage drops off as the current it supplies increases. We can model a practical voltage source using an ideal source Vs in series with an internal resistance Rs. Practical current source A practical current source supplies its rated current when its terminals are short-circuited but its current drops off as the load resistance increases. We can model a practical current source using an ideal current source in parallel with an internal resistance Rs.