Thirteen Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Not for Kids Only: a History of Surveillance Through Comic Book Images

Not For Kids Only: A History of Surveillance Through Comic Book Images Gary T. Marx I am here to fight for truth, justice and the American way. —Superman 1978 It's too bad for us "literary" enthusiasts, but it's the truth nevertheless—pictures tell any story more effectively than words. —W. M. Moulton (creator of Wonder Woman, and pioneer polygrapher) In Guernica Picasso expresses the tragedy that is taking place without showing piles of bloody flesh. The import- tant thing in art is after all to transpose reality into an image which is sufficiently enthralling and meaningful so that the viewer gets an even better grasp of that reality. —Jacques Ellul1 Gary T. Marx received his PhD from the University of California, Berkeley. He has held positions there and at Harvard and the University of Colorado. He is Professor Emeritus MIT and the author of Protest and Prejudice (1967); Undercover: Police Surveillance in America (1988); Undercover: Police Surveillance in Comparative Perspective (with C.J. Fijnaut 1995); Windows into the Soul: Surveillance and Society in an Age of High Technology (2017) and articles in the scholarly and popular press. He is rooted in the sociology of knowledge and in the centrality of reflexivity, but with the firm conviction that there are transcendent truths to pursue and fight for. Figuring them out is what it is all about. Additional information is at www.garymarx.net . Ivan Greenberg, illustrated by Everett Patterson and Joseph Canias, forward by Ralph Nader: The Machine Never Blinks A Graphic History of Spying and Surveillance Fantagraphics, Seattle, Wa., 2020, 132 p., $22.99 I grew up with Classic Comic Books and might even have used them as a cheat sheet for books I was supposed to have read. -

Fragility, Aid, and State-Building

Fragility, Aid, and State-building Fragile states pose major development and security challenges. Considerable international resources are therefore devoted to state-building and institutional strengthening in fragile states, with generally mixed results. This volume explores how unpacking the concept of fragility and studying its dimensions and forms can help to build policy-relevant under- standings of how states become more resilient and the role of aid therein. It highlights the particular challenges for donors in dealing with ‘chronically’ (as opposed to ‘temporarily’) fragile states and those with weak legitimacy, as well as how unpacking fragility can provide traction on how to take ‘local context’ into account. Three chapters present new analysis from innovative initiatives to study fragility and fragile state transitions in cross- national perspective. Four chapters offer new focused analysis of selected countries, drawing on comparative methods and spotlighting the role of aid versus historical, institu- tional and other factors. It has become a truism that one-size-fits-all policies do not work in development, whether in fragile or non-fragile states. This should not be confused with a broader rejection of ‘off-the-rack’ policy models that can then be further adjusted in particular situations. Systematic thinking about varieties of fragility helps us to develop this range, drawing lessons – appropriately – from past experience. This book was originally published as a special issue of Third World Quarterly, and is available online as an Open Access monograph. Rachel M. Gisselquist is a political scientist and currently a Research Fellow with UNU-WIDER. She works on the politics of the developing world, with particular attention to ethnic politics and group-based inequality, state fragility, governance and democratiza- tion in sub-Saharan Africa. -

Copyright by Mason Russell Mcwatters 2013

Copyright by Mason Russell McWatters 2013 The Dissertation Committee for Mason Russell McWatters certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Unworlding and Worlding of Agoraphobia Committee: ____________________________________ Paul C. Adams, Supervisor ____________________________________ Steven D. Hoelscher ____________________________________ Kathleen C. Stewart ____________________________________ Rebecca M. Torres ____________________________________ Leo E. Zonn The Unworlding and Worlding of Agoraphobia by Mason Russell McWatters, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2013 Dedicated to Catherine, my eternal sunshine. Acknowledgements I want to thank Paul Adams for his many years of support, guidance and mentorship during my both my master’s and doctoral studies. I first encountered Paul when I registered for his “Place, Politics and Culture” graduate seminar during my second semester in the interdisciplinary Latin American Studies master’s program. Up until that point, I had felt placeless at UT, floating between history, government and sociology courses that left me feeling uninspired and intellectually homeless. However, as soon as I set foot in Paul’s seminar, I knew I had found my proverbial academic home in geography. His genuine enthusiasm and creativity as a teacher made the study of place, space and landscape seem limitless, inviting and full of possibility. Through his eyes, mundane practices like walking through a city or looking at advertising in the suburbs became transformed into infinitely fascinating reflections on culture and society. I can say without a doubt that I would have never become a geographer were it not for Paul’s creative inspiration. -

Learn Workbook

LEARN THE WORKBOOK M THISGIRLISONFIRE.COM 2 STAGE 2: LEARN Congratulations! Well done on completing Stage 1 of this course, and taking a huge step away from feeling stuck, scared, and like you’re just existing rather than truly living. Now that you are in Stage 2 I know you’re feeling nervously excited, ready to change, committed, engaged and really believing that you CAN change. I am so fired up, knowing what’s in store for you over the next few parts! You are going to be making HUGE strides towards breaking the fear that is holding you back, learning to understand it, control it and shut down that inner voice that tells you “you can’t”. I’m here to show you that YOU CAN! Once again… take your time with this, don’t rush through it, ticking things off and diving on to the next thing. You’re going to be working through some uncomfortable things here, so take as long as you need to, there is no time scale and this will always be here for you. This is the part where you let it go to grow. By the time you finish this SECOND STAGE of the course, you will have learned how to: Cope with fear when it happens - because it WILL happen. Deal with “What’s the worst that could happen? Figure out if your fears are real, or if your brain is simply gossiping with you and freaking you out. Keep your emotions appropriate to your situation, and not blow them out of control. -

Essays from the Edge: Citizenship and the Outsider in Literature and History

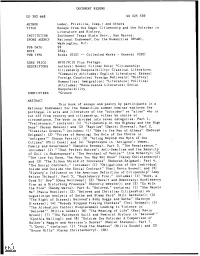

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 392 668 SO 025 539 AUTHOR Leder, Priscilla, Comp.; And Others TITLE Essays from the Edge: Citizenship and the Outsider in Literature and History. INSTITUTION Southwest Texas State Univ., San Marcos. SPONS AGENCY National Endowment for the Humanities (NFAH), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 234p. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Books; Citizen Role; *Citizenship; Citizenship Responsibility; Classical Literature; *Community Attitudes; English Literature; Essays; Foreign Countries; Foreign Nationals; *History; Humanities; Immigration; *Literature; Political Attitudes; *Renaissance Literature; Social Responsibility IDENTIFIERS *Greece ABSTRACT This book of essays and poetry by participants in a National Endowment for the Humanities summer seminar explores the portrayal in arts and literature of the "outsider" or "alien" who is cut off from country and citizenship, either by choice or circumstance. The book is divided into seven categories. Part 1, "Preliminary," contains: (1) "Citizenship on the Highway and the High Seas" (Susan Hanson); and (2) "Baptism" (Daniel Stevens). Part 2, "Classical Greece," includes:(1) "Ode to the Men of Athens" (Deborah Seigman) ;(2) "Voices of Warning: The Role of the Chorus in 'Antigone' (Susan Farris); (3) "Acting Beyond the Myth of the Citizen" (Phil Cook); and (4) "Sophrosyne in 'Antigone': Women, Family and Government" (Danette Bermea). Part 3, "The Renaissance," includes: (1) "-That Perfect Hatred': Anti-Semitism and the Banality of Evil in Shakespeare's 'The Merchant of Venice'" (JimMcGarry); (2) "The tore You Know, The Moor You May Not Know" (Carey Christenberry); and (3) "The Silken Shield of Innocence" (Deborah Seigman) .Part 4, "The Social Contract," includes:(1) "Obligations of the Individual Inside and Outside the Social Contract" (Karl Kevin Brown); and (2) "Slavery's Influence on the American Definition of Citizenship"(Amy Nelson Thibaut). -

Nine Inch Nails the Fragile Mp3, Flac, Wma

Nine Inch Nails The Fragile mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock Album: The Fragile Country: Europe Released: 1999 Style: Alternative Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1779 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1848 mb WMA version RAR size: 1742 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 856 Other Formats: TTA DTS DMF AC3 AUD AHX MMF Tracklist A1 Somewhat Damaged A2 The Day The World Went Away A3 The Frail A4 The Wretched B1 We're In This Together B2 The Fragile B3 Just Like You Imagined B4 Even Deeper C1 Pilgrimage C2 No, You Don't C3 La Mer C4 The Great Below D1 The Way Out Is Through D2 Into The Void D3 Where Is Everybody? D4 The Mark Has Been Made E1 10 Miles High E2 Please E3 Starfuckers, Inc. E4 Complication E5 The New Flesh F1 I'm Looking Forward To Joining You, Finally F2 The Big Come Down F3 Underneath It All F4 Ripe Notes The vinyl version of The Fragile features two tracks not available on the CD version: 10 Miles High and The New Flesh. Comes in a gatefold sleeve with 24 page booklet. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 606949 047313 Label Code: LC 06406 Matrix / Runout (Side A): 490-473-1-A Matrix / Runout (Side B): 490-473-1-B Matrix / Runout (Side C): 490-473-1-C Matrix / Runout (Side D): 490-473-1-D Matrix / Runout (Side E): 490-473-1-E Matrix / Runout (Side F): 490-473-1-F Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Nothing Nine The Fragile Records, 0694904732 Inch (2xCD, Album, 0694904732 US 1999 Interscope Nails Tri) Records Nine Nothing The Fragile 490 473-2 Inch Records, 490 473-2 Argentina 1999 -

1980-04-01.Pdf (3.1MB)

• News 3 Nothing in the least interesting, infor Cry Rape! mative, or that hasn't already been covered in the HOYA We have been raped. Arts 9 The Voice is very much like a woman: proud, sen A review of a play that closed two sitive, very aware of it's rightful place in the world. We weeks ago; a pretentious and verbose critique of an album that no one is go even run on our own cycle. But, unlike a woman, we ing to but anyway have a sense of honor, and that sense of honor has been . sullied by the shocking act that resulted in the theft of Cover 10 this newspaper, whose monetary value is approximately A last-ditch attempt to get people to get people to pick up our newsmagazine 1200 dollars. But the issue is not money, but rape. We in spite of the cliche-ridden prose and demand satisfaction, and, aga,in like a woman, we pro non-sequitor commentary. Behind bably won't get it. Sports II The facts in the case are simple. We work hard all Now that the basketball season is week gathering the news, sports, and features that you over, pretty lean pickings. Reports on see tastefully presented in our pages. Monday night we minor sports that get almost no funding theLinM and lose all the time. take what we in the newspaper business call "flats", worth around 1200 dollars, to our printers, the Nor C.S. Lewis once said that thern Virginia Sun. Sometime between nine and nine "You always hurt the one you eleven, the flats, (worth over a thousand dollars), were Board 0/ Worth love", and he almost certainly agree that, at least at Georgetown found to be missing, searched for, declared officially Mark Whimp. -

The Sherlock Holmes Paradigm in Contemporary Crime Series

Echoing the Eccentric Genius – The Sherlock Holmes Paradigm in Contemporary Crime Series Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philologischen Fakultät der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg i. Br. vorgelegt von Isabell Ewers aus Baden-Baden SS 2020 Erstgutachter/in: Frau Prof. Dr. Barbara Korte Zweitgutachter/in: Frau PD Dr. Nicole Falkenhayner Vorsitzende/r des Promotionsausschusses der Gemeinsamen Kommission der Philologischen und der Philosophischen Fakultät: Prof. Dr. Dietmar Neutatz Datum der Fachprüfung im Promotionsfach: 22.03.2021 Table of contents 0. Introduction 4-10 1. The creation and popularisation of the eccentric genius 1.1. Explaining the continuum of an ambivalent fascination 1.1.1. Eccentrics and geniuses: terminology, parallels and the question of definition 11-12 1.1.2. “Great men” or madmen? The eccentric genius in the eyes of the Victorians 13-21 1.1.3. A new working definition based on family resemblance: ten key features 22-31 1.2. Adapting the paradigm to the small screen 1.2.1. The ‘what’ and the ‘why’: a sociological turn of adaptation studies 32-41 1.2.2. The ‘how’: medium-specific codes and the potential of television series 41-48 2. The Sherlock Holmes stories by Arthur Conan Doyle 2.1. The (integrational) functions of an eccentric genius 2.1.1. The birth and background of the Sherlock Holmes paradigm 49-53 2.1.2. A genius put to use: Holmes’s profession and its attraction for society 53-69 2.1.3. Decadence, domestic life and mental state of a singular and other-worldly (?) genius 69-78 2.2. -

THE MAD GENIUS: a RETROSPECT to John Barrymore

Warners’ Edward G. Robinson, will now go THE MAD GENIUS: A RETROSPECT to John Barrymore. No reason is given for the switch, but surely Warners, delighted by By Greg Mank Svengali, wants a follow-up similar in style and scope. For 1931 moviegoers, beholding At Last! Barrymore on the screen is akin to 2010 audi- The Great John BARRYMORE ences watching a rock star—a crazy, unbridled At His Zenith! talent, shooting off sparks of what Greta Garbo –Warner Bros. Publicity for later hailed as the man’s “divine madness.” The Mad Genius, 1931 Barrymore himself had discussed film- ing Hamlet for Warner Bros., but The Genius Monday, March 9, 1931. impressed the studio as the perfect vehicle Bella Vista is an estate, almost fairy- to follow Svengali—fresh enough to avoid tale in its extravagance, nestled on a seeming a carbon copy, and melodramatic mountain in Beverly Hills. In the pre-dawn enough to allow the star to explode in his darkness, the virtual castle, with a tower, frenetic fashion. pools, and aviary, glistens under a waning While Svengali traced back to George Du full moon. The entranceway gate bears a Maurier’s venerable 1894 novel Trilby, many coat of arms, personally designed by Bella stage productions, and at least three film Vista’s master and revealing his repellent versions, The Genius has no such pedigree. Marian Marsh as Trilby and John Barrymore as the title character in Svengali self-image: a serpent wearing a crown. (1931). Warner Bros.’ high hopes for this film’s popularity inspired production It’s based on a Broadway-bound play by As the master arises, he probably doesn’t of The Mad Genius. -

Cinéma, De Notre Temps

PROFIL Cinéma, de notre Temps Une collection dirigée par Janine Bazin et André S. Labarthe John Ford et Alfred Hitchcock Le loup et l’agneau le 4 juillet 2001 Danièle Huillet et Jean-Marie Straub le 11 juillet 2001 Aki Kaurismäki le 18 juillet 2001 Georges Franju, le visionnaire le 25 juillet 2001 Rome brûlée, portrait de Shirley Clarke le 1er août 2001 Akerman autoportrait le 8 août 2001 23.15 tous les mercredis du 4 juillet au 8 août Contact presse : Céline Chevalier / Nadia Refsi - 01 55 00 70 41 / 70 40 [email protected] / [email protected] La collection Cinéma, de notre temps Cinéma, de notre temps, collection deux fois née*, c'est tout le contraire d'un pèlerinage à Hollywood, " cette marchande de coups de re v o l v e r et (…) de tout ce qui fait circuler le sang ". C'est la tentative obstinée d'éclairer et de montre r, dans chacun des films qui la composent, comment le cinéma est bien l'art de notre temps et combien il est, à ce titre, redevable de bien autre chose que de réponses mondaines, de commentaires savants ou de célébrations. La programmation de cette collection est l'occasion de de constater combien ces " œuvres de télévision " échappent aux outrages du temps et constituent une constellation unique au monde dans le ciel du 7è m e a rt . Thierry Garrel Directeur de l'Unité de Programmes Documentaires à ARTE France *En 1964, Janine Bazin et André S Labarthe créent Cinéastes de notre temps. -

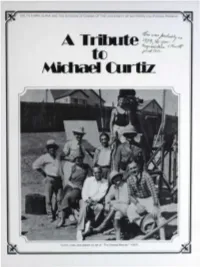

A Tribute to Michael Curtiz 1973

Delta Kappa Alpha and the Division of Cinema of the University of Southern California present: tiz November-4 * Passage to Marseilles The Unsuspected Doctor X Mystery of the Wax Museum November 11 * Tenderloin 20,000 Years in Sing Sing Jimmy the Gent Angels with Dirty Faces November 18 * Virginia City Santa Fe Trail The Adventures of Robin Hood The Sea Hawk December 1 Casablanca t December 2 This is the Army Mission to Moscow Black Fury Yankee Doodle Dandy December 9 Mildred Pierce Life with Father Charge of the Light Brigade Dodge City December 16 Captain Blood The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex Night and Day I'll See You in My Dreams All performances will be held in room 108 of the Cinema Department. Matinees will start promptly at 1:00 p.m., evening shows at 7:30 p.m. A series of personal appearances by special guests is scheduled for 4:00 p.m. each Sunday. Because of limited seating capacity, admission will be on a first-come, first-served basis, with priority given to DKA members and USC cinema students. There is no admission charge. * If there are no conflicts in scheduling, these programs will be repeated in January. Dates will be announced. tThe gala performance of Casablanca will be held in room 133 of Founders Hall at 8:00 p.m., with special guests in attendance. Tickets for this event are free, but due to limited seating capacity, must be secured from the Cinema Department office (746-2235). A Mmt h"dific Uredrr by Arthur Knight This extended examination of the films of Michael Only in very recent years, with the abrupt demise of Curtiz is not only long overdue, but also altogether Hollywood's studio system, has it become possible to appropriate for a film school such as USC Cinema. -

SING-A-LONG BOOK (Revision Two, August, 2007)

AN UNOFFICIAL ALLEY SING-A-LONG BOOK (Revision Two, August, 2007) AN UNOFFICIAL ALLEY SING-A-LONG BOOK (Revision Two, August 2007 Acknowledgments: Original Concept, Research, Layout and Design: Robert V. Carey Assistant: Joanne M. Binder Edited by: Robert V. Carey & Paul Rose Revision One Research and Layout: Paul Rose Revision Two Research and Layout: Paul Rose Special Appreciation for Sponsorship: Richard McCall, Dave Chapman, Kitty Explanation of Abbreviations (w) “words by” (P) “Popularized by” (CR) "Cover Record" i.e., a (m) “music by” (R) “Rerecorded by” competing record made of the same (wm) “words and music by” (RR) “Revival Recording” song shortly after the original record (I) “Introduced by” (usually the first has been issued record) NARAS Award Winner –Grammy Award The contents of this volume are intended solely for entertainment purposes. The contents contained herein are not to be distributed in whole or in part for commercial use. All copyrights, international and otherwise are secured and reserved by the copyright holders. For all works contained herein: Unauthorized copying, arranging, adapting, recording or public performance for commercial gain is an infringement of copyright. If you “accidentally” take this book home, shame on you. These books have been donated by other patrons of The Alley. Please know that each copy cost one of your fellow singers about $14. CALL ME IRRESPONSIBLE .......................... 12 A CAN’T HELP FALLING IN LOVE WITH YOU ..................................................................... 14 A, YOU’RE ADORABLE (THE ALPHABET CAN’T HELP LOVIN’ DAT MAN .................. 13 SONG) ........................................................... 1 CAN’T WE BE FRIENDS ............................... 14 ABA DABA HONEYMOON, THE ..................... 1 CAROLINA IN THE MORNING ....................