Greekness, Identity and New Greek Cuisine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FOOD ENTREES Taramosalata • Cod Roe, Lemon, Onion, Bread, Spices Whole Fish Sbroiled and Served with Evoo, Kleftiko Briami Vegetable Medley Oven Oregano and Lemon

BRUNCH LUNCH SERVED TILL 2PM SERVED TILL 4PM avli's cassoulet $13 SANDWICHES SERVED TILL 4PM Gigandes beans, Greek sausage, basted egg, dakos rusks CHOOSE: CUP OF SOUP, SIDE SALAD, OR GREEK FRIES three eggs $10 avli's gyros beef & lamb slices, pita, onions, oregano, tomato & tzatziki $12 Served any way you like, w/toast, home style potatoes strapatsada $10 bbq pulled lamb sauteed onions, tangy sauce, fried leeks, on ciabatta bread $12 Grated tomatoes, eggs, EVOO, herbs, home style potatoes chicken breast chargrilled, onions, tomato, Tzatziki, on a pita $12 greek yogurt parfait $8 chicken tirokafteri grilled chicken breast, spicy feta, on a focaccia $12 Greek yogurt, housemade granola, Greek honey eggplant & zucchini with carmelized onions, arugula, feta, on ciabatta bread $12 greek yogurt and fruit $10 Greek yogurt, seasonal fruit, Greek honey lamb burger ground leg of lamb, herbs, spices, spicy feta, on ciabatta bread $12 three cheese omelet $10 spartan tacos Greek sausage, saganaki cheese, fried onions, spicy tzatziki, tortilla $11 eggs, feta, kefalograviera, manouri, home style potatoes pulled chicken chicken breast, onions, herbs, riganati sauce, on ciabatta bread $12 greek omelet $11 solomos smoked salmon, red onions, dill cheese, EVOO, on a focaccia $12 feta, spinach, onions, oregano, home style potatoes gyros omelet $11 vegetarian whole wheat pita, arugula, artichokes, peppers, olives, feta, dressing $12 Gyros added to Greek omelet, home style potatoes gluten free pita an additional $1.50 tsoureki french toast $10 Greek sweet bread, eggs, fresh milk, sugar, cinnamon pancakes $9 buttermilk pancakes, Greek honey, fruit applewood smoked bacon $4 gluten free vegetarian evoo=extra virgin olive oil avli homestyle potatoes $3 thick greek style toast with Greek Orange Marmalade $3 SPREADS KIRIO PIATO THALLASINA SEAFOOD ENTREES SERVED WITH PITA BREAD $7 TRADITIONAL ENTREES Taramosalata • cod roe, lemon, onion, bread, spices Whole Fish sbroiled and served with evoo, Kleftiko Briami Vegetable medley oven oregano and lemon. -

Signature Courses at Webster Athens

SIGNATURE COURSES AT WEBSTER ATHENS www.webster.edu.gr Archaeological Sites of Greece- Introduction to Archaeology: ANSO 1075 (3) The On-Site Experience: Archaeology, defined simply, is the study of humanity ANSO 3110 (3) through its material manifestations. It is also about trying The course is designed to introduce students to basic to understand something of our common humanity by archaeological site fields in the most beautiful settings examining the physical traces of the people of the past. in Greece and train them in the basics of These traces don't have to be old, and you don't have to archaeological survey practices. Students will work dig for them; the vast majority of archaeological work, with the course facilitator and will be visiting various however, does involve digging up old materials people archaeological sites in Athens- Acropolis, Ancient have left behind. The key, then, is the method. How do Agora, and throughout Greece: Epidaurus, Mycenae, you deal with the material? What kind of conclusions can Cape Sounion, Ancient Olympia, Delphi. Also, there be drawn from it, and how do you arrive at them? We will are visits to The National Archaeological Museum, examine the scope and usefulness of archaeology. Benaki museum, museums in Ancient Olympia, Delphi Epidaurus, Mycenae. There will be lectures and discussions on local prehistory, history, archaeology Greek Art & Archaeology: and ecology. The course combines theoretical classes with visits to the archaeological sites and students will ANSO 2025/ ARHS 2350 (3) have the opportunity to explore Greece, its museums A survey of the art and archaeology of Greece from the and monuments. -

Brunch Cocktails New Wine, Ancient Prices

cocktails krasi mimosa Greek bubbles, mango juice, dill 10 otto’s spritz brunch Otto’s vermouth, concord grape syrup, Greek bubbles 12 baklava muffin walnuts, Greek honey, cinnamon, clove 4 each aphrodite’s bellini bougatsa for two custard, semolina, phyllo, Greek bubbles, ouzo-infused apricots 12 powdered sugar, cinnamon 12 circe’s potion koulouri homemade sesame bread, Greek honey butter, Retsina, chamomile, grapefruit, spoon sweet 8 soda water 12 trahana bulgur, almond butter, banana, figs, coconut flakes, pistachios, Greek honey 10 bloody mitsos Psychis mastiha, housemade bloody mix, dips tzatziki, htipiti, taramosalata, sourdough 14 spicy feta olives, chicken skin 12 FIX it +4 solomo smoked salmon, lemon-dill manouri cream cheese, boiled egg, caper berries, carob bread 16 spiked frappe Metaxa, Nescafe cafe, vanilla syrup 14 tsoureki Merenda, kataifi crumble, Metaxa glazed apples, whipped cream 10 per slice greek negroni lalagites lemon-mizithra filled fried pancakes, grilled pineapple infused tsipouro, carob honey syrup, lemon zest 12 Otto’s vermouth, Bonanto 16 pita fresh-baked savory pie 12 add fried egg +2 saganaki fried egg, kasseri, feta, boukovo, cherry tomatoes, barley rusk 14 strapatsada tomato and feta scramble, mushrooms, New Wine, frigania toast 16 Ancient Prices strata loukaniko, spinach, olives, feta, mixed greens 14 In ancient Greece, when folks brought friends around to drink, the wine was free. Now we can’t peinirli tomato, pepper, onion, Metsovone, do that, we have rent and electricity to pay. sunny-side-up egg 12 What we can do is offer $20 carafes hand picked by us, your friends. Not free, but pretty close. Also, avga me patates sunny-side-up eggs, louza, Betty White is Greek. -

Desserts Gelatos Beverages Kids Menu

Desserts Beverages Persian Mini Baklavas Tea Greek honey, walnuts, pistachios, almonds, cinnamon/ English Earl Grey rose water syrup & mocha gelato 8 Galaktoboureko Green Tea Jasmine vanilla bean semolina custard, phyllo brittle, English Breakfast Decaf orange blossom syrup 8 Lemon Zinger Mountain Greek Souffle Sokolata Iced Tea a blend of dark & milk chocolate, hint of Greek coffee, served with vanilla gelato 8 3 Greek Cheesecake Cafe crispy phyllo base, whipped greek yogurt cheesecake, strawberry metaxa brandy topping 8 Greek Coffee Ekmek Sto Potiri 100% arabica single 3 • double 5 crispy kataifi, vanilla custard, grand marnier, Frappè whipped cream topping 8 served on the rocks with or without milk 4 Kataifi American Coffee 2.5 walnuts, pistachios, honey syrup, served with honey vanilla gelato 8 Espresso single 3 • double 5 Risogalo Brulè Cappuccino 6.5 our version of the traditional rice pudding Freddoccino different every season 8 6.5 Mykonos Crepe crepe, chocolate hazelnut praline, banana & Hot Delights chocolate parfait gelato 8 Cozy Chamomile lemon & Greek honey 3 Zesti Sokolata Greek hot chocolate, cinnamon, Gelatos creamy froth & honey 4 Kaimaki vanilla, mastiha, salepi Chocolate Parfait Bottled Water hazelnut praline, dark ghana chocolate, pistachio, (16 oz.) Bottled Water 2.5 orange confit & metaxa brandy Vikos Natural Mineral Water 9 Siko Pellegrino Sparkling Water 9 vanilla & kalamata dry fig soaked in ouzo Souroti Sparkling Water Frappè 9 mocha, cinnamon & cognac choice of three scoops Kids Menu 8 Grilled Cheese 8.5 Chicken Fingers 8.5 Greek Pizza 8.5 Mac N’ Cheese 8.5 Executive Chef: Sotirios Kontos Catering Available & Party Room for All Occasions Prices subject to change without notice. -

Kordas Menu English

κορδας Soups Santorini's Tomato Soup { Manestra } Soup of the day Salads Traditional Greek Salad with real Feta Cheese Fresh Greens Sautée virgin olive oil and lime dressing Ceasar's Salad Grilled chicken, lettuce, carrot and cucumber flakes, croutons, sauce Santorini's Salad tomatoes, anchovies, caper butoons, caper leaves, cucumber, goat cheese, onion and traditional Greek dried bread κορδας Starters Strapatsada { Greek dish with scrambled eggs, fresh tomatoes and spicies } Feta Rolls Topped with Tomato Marmalade Mushroom Homemade Tart Grilled Octopus with Fava { Yellow Pea Purée } Shrimps Saganaki - Ouzo and Feta Sauce Mushrooms Sautée in Wine and Thyme Sauce Mussels in Mustard and Beer Sauce Fried Potatoes Spinach Gratinee with Garlic and Cheese κορδας Kordas’ Specials Beef filet with mashed potatoes-vegetable and béarnaise sauce Pork tenderloin stuffed with sundried tomato-spinach and cold spaghetti salad Frame lamb with country potatoes and meat sauce flavored with rosemary See bass with risotto in lemon sauce- asparagus and meat sauce Manestra with chicken filet and local sour cheese Risotto mohito with chicken Risotto Daiquiri κορδας Fresh Grilled Meat Beef Steak served with Potato purée and Green Olive Sauce Pork Steak with Jacket Potato and Plum Sauce Lamb Chops in Rosemary Sauce and Grilled Mushrooms Greek Traditional Sausage with Herbs and Spices served with Eggplant Purée Chicken Souvlaki served with Grilled Vegetables and Mustard Sauce Grilled Burger with Grilled Vegetables and Jacket Potato Selection of Grilled Meat for -

Holy and Great Council Moving Forward; Patriarch Arrives Bartholomew Makes Last-Minute Request, but Russians and Other Churches Not Attending

S O C V st ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ W ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ E 101 ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald anniversa ry N www.thenationalherald.com A wEEkly GrEEk-AmEriCAN PuBliCATiON 1915-2016 VOL. 19, ISSUE 975 June 18-24, 2016 c v $1.50 Holy and Great Council Moving Forward; Patriarch Arrives Bartholomew Makes Last-Minute Request, but Russians and Other Churches not Attending By Theodore Kalmoukos to 28. For months now, a Small Synaxis of the Primates has been CRETE, GREECE – The Ortho - scheduled for June 17th as well. dox Church from throughout The agenda items are: 1) The the world will gather for a his - mission of the Orthodox Church toric Holy and Great Council in the contemporary world; 2) (also called the Great Synod) on The Orthodox diaspora; 3) Au - Crete, scheduled at press time tonomy and the manner of its from June 19 through 27, to proclamation; 4) The sacrament witness its unity and strength of marriage and its impedi - speaking with one voice and one ments; 5) The importance of heart, despite attempts made by fasting and its observance to - some Local Orthodox Churches day; and 6) The relationship of to postpone it. the Orthodox Church with the Specifically, the Churches of rest of the Christian world. Bulgaria, Russia, Georgia, and On June 15, Bartholomew Antioch decided not to partici - made a last-minute plea inviting pate in the Synod, invoking rea - all the Churches to participate. sons about the texts and docu - He was warmly greeted at the ments and also the ongoing airport by His Eminence Arch - dispute between the ancient and bishop Irineos of Crete and historic Patriarchates of Antioch members of the Holy Synod of and Jerusalem over the issue of the Semi-Autonomous Church the canonical and ecclesiastical of Crete, Undersecretary of For - jurisdiction of the Archdiocese eign Affairs of Greece Ioannis of Qatar, established some three Amanatidis, the Mayor of Cha - years ago by the Patriarchate of nia Tasos Vamboukas, and other TNH/COSTAS BEJ Jerusalem. -

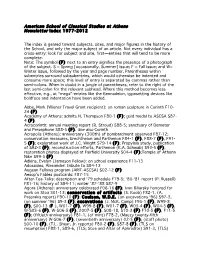

American School of Classical Studies at Athens Newsletter Index 1977-2012 the Index Is Geared Toward Subjects, Sites, and Major

American School of Classical Studies at Athens Newsletter Index 1977-2012 The index is geared toward subjects, sites, and major figures in the history of the School, and only the major subject of an article. Not every individual has a cross-entry: look for subject and site, first—entries that will tend to be more complete. Note: The symbol (F) next to an entry signifies the presence of a photograph of the subject. S = Spring [occasionally, Summer] Issue; F = Fall Issue; and W= Winter Issue, followed by the year and page number. Parentheses within subentries surround subsubentries, which would otherwise be indented and consume more space; this level of entry is separated by commas rather than semi-colons. When in doubt in a jungle of parentheses, refer to the right of the last semi-colon for the relevant subhead. Where this method becomes less effective, e.g., at “mega”-entries like the Gennadeion, typesetting devices like boldface and indentation have been added. Abbe, Mark (Wiener Travel Grant recipient): on roman sculpture in Corinth F10- 24 (F) Academy of Athens: admits H. Thompson F80-1 (F); gold medal to ASCSA S87- 4 (F) Acrocorinth: annual meeting report (R. Stroud) S88-5; sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone S88-5 (F). See also Corinth Acropolis (Athens): anniversary (300th) of bombardment observed F87-12; conservation measures, Erechtheion and Parthenon F84-1 (F), F88-7 (F), F91- 5 (F); exploration work of J.C. Wright S79-14 (F); Propylaia study, publication of S92-3 (F); reconstruction efforts, Parthenon (K.A. Schwab) S93-5 (F); restoration photos displayed at Fairfield University S04-4 (F);Temple of Athena Nike S99-5 (F) Adkins, Evelyn (Jameson Fellow): on school experience F11-13 Adossides, Alexander: tribute to S84-13 Aegean Fellows program (ARIT-ASCSA) S02-12 (F) Aesop’s Fables postcards: F87-15 After-Tea-Talks: description and ‘79 schedule F79-5; ‘80-‘81 report (P. -

B R E a K F a S T

B r e a k f a s t Greek Breakfast Vegetarian Breakfast Classic Breakfast Mini Greek Salad , Olives Avocado salad with Peppers, Eggs of your choice Kayanas with Salted Pork, Portobello Mushrooms Tost, Butter, Honey Yogurt with Honey sauted with Spinach, Homemade jam, Milk, Carob bread with Feta Mousse Quinoa with Yogurt and Tahini Hazelnut praline, Yogurt, Orange Juice Cereals Classics Chef's preference Eggs of your choice on toasted bread Pancakes with Smoked Salmon and Cream Cheese Omelette of your choice French Toast with Poached Eggs, Avocado, Lime and Chilly Scrambled eggs Scrambled Eggs with Crab, Cream Cheese and Fish Herring Raw Eggs Royale or Florentine or Benedict Patato Bread with Fried Eggs, Pastrami and grilled Tomato Mini Greek Salad Traditional Strapatsada served on Grilled Tomato and Bread Pancakes with Yogurt, Honey and Thyme Pancakes with Hazelnut, Banana and Biscuits Caramelized Tsoureki with Vanilla Cream Chocolate Ganache with Peanut Butter, Biscuits and Caramel Bakery Butter Croissant Chocolate Croissant Greek Yogurt & Fresh Fruits Greek Sweet Bread -Tsoureki Greek Yogurt with Honey, Nuts & Thyme Cake of the Day Granola, Strawberries, Kiwi, Raisins & Nuts Fresh Bread Greek Yogurt with Fresh Fruits Fresh Fruit Salald Beverages and Juices Espresso Filter Coffee Orange Juice Freddo Espresso Americano Carrot , Orange & Ginger Juice Cappuccino Black Tea Fresh Mixed Juice of the day Freddo Cappuccino Green Tea Hot chocolate Coffee Latte Lemon Tea Cold Chocolate Greek Coffee Milk / Almond Milk If you have any allergies or food intolerance, please advice a member of our staff Decaffeinated coffes are also available . -

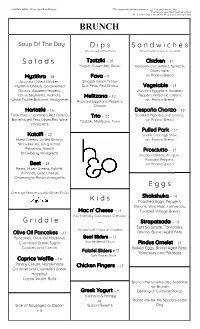

Menu Items Also Available

11:00PM-4:00PM | Weekends & Bank Holidays *The consumption of raw or uncooked eggs, meat, poultry or shellfish may increase your risk of food borne illness. Please inform your server of any allergies or dietary restrictions. BRUNCH Soup Of The Day D i p s S a n d w i c h e s Served with Pita Points Served with Crisps or Crudités Tzatziki – 10 – 17 S a l a d s Chicken Yogurt, Cucumber, Garlic Haloumi, Cucumbers, Spinach, Olive Paste, Myzithra – 18 Fava – 9 on Panino Bread Arugula, Grilled Chicken, Smooth Greek Yellow Myzithra Cheese, Caramelized Split Peas, Red Onions Vegetable – 13 Onions, Roasted Peppers, Zucchini, Eggplant, Roasted Citrus Segments, Walnuts, Melitzana – 13 Peppers, Balsamic Cream, White Truffle Balsamic Vinaigrette Roasted Eggplant, Peppers, on Panino Bread Onions Horiatiki – 16 Despaña Chorizo – 15 Tomatoes, Cucumbers,Red Onions, Trio – 22 Sautéed Peppers and Onions, Barrel-Aged Feta,Olives,Red Wine Tzatziki, Melitzana, Fava on Panino Bread Vinaigrette Pulled Pork – 17 Kataïfi – 22 Greek Cabbage Slaw, Mixed Greens, Grilled Shrimp, on Panino Bread Strawberries, Gorgonzola, Pistachios, Kataïfi, Prosciutto – 17 Strawberry Vinaigrette Kasseri Cheese, Arugula, Roasted Peppers, Beet – 18 on Panino Bread Beets, Mixed Greens, Falafel, Almonds, Goat Cheese, Champagne Raisin Vinaigrette E g g s Dressings Feature Locally-Owned EVOO Shakshuka – 14 K i d s Poached Eggs, Peppers, Onions, Vine Ripe Tomatoes, Mac n’ Cheese – 11 Toasted Village Bread Kid Friendly Cavatappi Cheddar G r i d d l e — Strapatsada – 13 Soft Scramble, Tomatoes, -

GREEK FOOD SOLIDARITIES (ALLILEGGIÍ) Communalism Vis-À-Vis Food in Crisis Greece

“NEW” GREEK FOOD SOLIDARITIES (ALLILEGGIÍ) Communalism vis-à-vis Food in Crisis Greece James Verinis, Roger Williams University, Bristol (USA) In this paper I extend the anthropological analyses of “new” solidarity (allileggií) networks or movements in Greece to rural regions and agricultural life as well as new groups of people. Food networks such as the “potato movement”, which facilitates the direct sales of agricultural produce, reveals rural aspects of networks that are thought to be simply urban phenomena. “Social kitch- ens” are revealed to be humanistic as well as nationalistic, bringing refugees, economic migrants, and Greeks together in arguably unprecedented ways. Through a review of such food solidarity movements – their rural or urban boundaries as well as their egalitarian or multicultural tenets – I consider whether they are thus more than mere extensions of earlier patterns of social solidarity identified in the anthropological record. Keywords: solidarity, rural–urban dichotomy, ethno-national identity, globalization, food “New” Greek Solidarity Movements well as the seemingly paradoxical evidence I had col- When I first began to reflect on the work I had con- lected during my dissertation fieldwork – that many ducted for my Ph.D. dissertation between 2008 and bonds between Greeks and non-Greeks in rural ar- 20101 in the southern Peloponnesian prefecture of eas had strengthened since the early 1990s.3 What is Laconia (which was primarily about Greek/non- more, to say that economic migrants are not simply Greek farmer relationships [Verinis 2015]), I sought exploited by neoliberalism is generally anathema to to account for some statistical evidence that many anthropology, despite its interest in data niches vis- non-Greeks had left Greece since the onset of the fi- à-vis qualitative approaches such as my focus on a nancial crisis.2 Mainstream media has focused heav- certain relatively small group of economic immi- ily on the rise of support for the Greek far right, par- grants. -

Brunchy Cocktails Breakfast & Pastries OPSO Egg Classics Larder Delicacies Mains to Share Sides

Brunchy Cocktails Larder Delicacies Chios Vibes 10 Tzatziki 9 Mastiha, Aperol, sparkling wine, pineapple Roasted garlic yoghurt spread, sesame za’atar Pink Mimosa 10 Feta Kataifi 12.5 Sparkling wine, grapefruit, peach bitters Thyme honey, sesame seeds Hugo Dates Raspberry 10 Spanakopita 15 Sparkling wine, raspberry cordial, mint Handmade spinach pie, feta cheese & Greek yoghurt Freddo Espresso Martini 10 Dakos Salad 17 Metaxa, Rakomelo, espresso, vanilla Greek salad, Kytherian olive oil rusks, 18 months barrel-matured feta Peinirli Tigania 14 Lemon-oregano chicken, tzatziki, peinirli pastry Breakfast & Pastries OPSO Granola 12 Oat & hazelnut crumble, cocoa nibs, thyme honey Mains to Share bitter chocolate, pomegranate, chilled blueberries Skate Wing 32 Very Berry Pancake 14 ‘Greek’ bottarga, brown butter, lemon Mascarpone cream, strawberry jam, chilled fresh berries Prime Rib Eye Steak 400gr 48 Lotus Pancake 15 Tartare sauce Lotus cookie crumble, milk chocolate cream, bananas, salted caramel Iberico Pork Steak Stifado 280gr 41 Bougatsa 17 Secreto cut, onions Thessaloniki’s traditional sweet pastry, semolina custard, cinnamon, icing sugar ‘Paidakia’ 380gr 53 Salted Caramel Choux 12 Wagyu short-rib chops, oregano, green olives ‘tsakistes’ Homemade pate choux, vanilla ice cream, milk chocolate caramel Sides OPSO Egg Classics Lettuce Salad 7.5 Green Kayanas 16 Grilled baby gem, feta cheese, spring onion, dill Scrambled eggs, spicy avocado mash, wilted cherry tomatoes 18 months barrel matured feta, toasted sourdough bread Potato Mash 6.5 Lemon-oregano -

University College London Department of Mtcient History a Thesis

MYCENAEAN AND NEAR EASTERN ECONOMIC ARCHIVES by ALEXMDER 1JCHITEL University College london Department of Mtcient History A thesis submitted in accordance with regulations for degree of Doctor of Phi]osophy in the University of London 1985 Moe uaepz Paxce AneKceee Ko3JIo3oI nocBaeTca 0NTEN page Acknowledgments j Summary ii List of Abbreviations I Principles of Comparison i 1. The reasons for comparison i 2. The type of archives ("chancellery" and "economic" archives) 3 3. The types of the texts 6 4. The arrangement of the texts (colophons and headings) 9 5. The dating systems 6. The "emergency situation" 16 Note5 18 II Lists of Personnel 24 1. Women with children 24 2. Lists of men (classification) 3. Lists of men (discussion) 59 a. Records of work-teams 59 b. Quotas of conscripts 84 o. Personnel of the "households" 89 4. Conclusions 92 Notes 94 III Cultic Personnel (ration lists) 107 Notes 122 IV Assignment of Manpower 124. l.An&)7 124 2. An 1281 128 3. Tn 316 132 4.. Conclusions 137 Notes 139 V Agricultural Manpower (land-surveys) 141 Notes 162 page VI DA-MO and IX)-E-R0 (wnclusions) 167 1. cia-mo 167 2. do-e-io 173 3. Conclusions 181 No tes 187 Indices 193 1. Lexical index 194 2. Index of texts 202 Appendix 210 1. Texts 211 2. Plates 226 -I - Acknowledgments I thank all my teachers in London and Jerusalem . Particularly, I am grateful to Dadid Ashen to whom I owe the very idea to initiate this research, to Amlie Kuhrt and James T.