Transcription Factor Zeb2 Regulates Commitment to Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell and Monocyte Fate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Olig1 and Sox10 Interact Synergistically to Drivemyelin Basic

The Journal of Neuroscience, December 26, 2007 • 27(52):14375–14382 • 14375 Cellular/Molecular Olig1 and Sox10 Interact Synergistically to Drive Myelin Basic Protein Transcription in Oligodendrocytes Huiliang Li,1 Yan Lu,2 Hazel K. Smith,1 and William D. Richardson1 1Wolfson Institute for Biomedical Research and Department of Biology, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, United Kingdom, and 2Medical Research Council, Clinical Sciences Centre, Imperial College London, London W12 0NN, United Kingdom The oligodendrocyte lineage genes (Olig1/2), encoding basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors, were first identified in screens for master regulators of oligodendrocyte development. OLIG1 is important for differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursors into myelin- forming oligodendrocytes during development and is thought to play a crucial role in remyelination during multiple sclerosis. However, itisstillunclearhowOLIG1interactswithitstranscriptionalcofactorsandDNAtargets.OLIG1wasreportedlyrestrictedtomammals,but we demonstrate here that zebrafish and other teleosts also possess an OLIG1 homolog. In zebrafish, as in mammals, Olig1 is expressed in the oligodendrocyte lineage. Olig1 associates physically with another myelin-associated transcription factor, Sox10, and the Olig1/Sox10 complex activates mbp (myelin basic protein) transcription via conserved DNA sequence motifs in the mbp promoter region. In contrast, Olig2 does not bind to Sox10 in zebrafish, although both OLIG1 and OLIG2 bind SOX10 in mouse. Key words: Olig1; Olig2; Sox10; Mbp; oligodendrocyte; myelin; zebrafish; mouse; evolution; development Introduction directly regulates Mbp transcription (Stolt et al., 2002), and over- Myelin, the multilayered glial sheath around axons, is one of the expression of SOX10 alone is sufficient to induce myelin gene defining features of jawed vertebrates (gnathostomes). It is expression in embryonic chick spinal cord (Liu et al., 2007). -

Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis of KRAS Mutant Cell Lines Ben Yi Tew1,5, Joel K

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of KRAS mutant cell lines Ben Yi Tew1,5, Joel K. Durand2,5, Kirsten L. Bryant2, Tikvah K. Hayes2, Sen Peng3, Nhan L. Tran4, Gerald C. Gooden1, David N. Buckley1, Channing J. Der2, Albert S. Baldwin2 ✉ & Bodour Salhia1 ✉ Oncogenic RAS mutations are associated with DNA methylation changes that alter gene expression to drive cancer. Recent studies suggest that DNA methylation changes may be stochastic in nature, while other groups propose distinct signaling pathways responsible for aberrant methylation. Better understanding of DNA methylation events associated with oncogenic KRAS expression could enhance therapeutic approaches. Here we analyzed the basal CpG methylation of 11 KRAS-mutant and dependent pancreatic cancer cell lines and observed strikingly similar methylation patterns. KRAS knockdown resulted in unique methylation changes with limited overlap between each cell line. In KRAS-mutant Pa16C pancreatic cancer cells, while KRAS knockdown resulted in over 8,000 diferentially methylated (DM) CpGs, treatment with the ERK1/2-selective inhibitor SCH772984 showed less than 40 DM CpGs, suggesting that ERK is not a broadly active driver of KRAS-associated DNA methylation. KRAS G12V overexpression in an isogenic lung model reveals >50,600 DM CpGs compared to non-transformed controls. In lung and pancreatic cells, gene ontology analyses of DM promoters show an enrichment for genes involved in diferentiation and development. Taken all together, KRAS-mediated DNA methylation are stochastic and independent of canonical downstream efector signaling. These epigenetically altered genes associated with KRAS expression could represent potential therapeutic targets in KRAS-driven cancer. Activating KRAS mutations can be found in nearly 25 percent of all cancers1. -

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE LEGENDS Supplemental Figure S1. RBPJ

Xie et al. SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE LEGENDS Supplemental Figure S1. RBPJ correlates with BTIC marker expression. A-D. The TCGA GBM dataset was downloaded and correlations analyzed by R. RBPJ mRNA levels were highly correlated with (A) Olig2, (B) Sox2, (C) CD133, and (D) Sox4 levels. E. RBPJ is preferentially expressed in proneural glioblastomas. The glioblastoma TCGA dataset was interrogated for RBPJ mRNA expression segregated by transcriptional profile. The proneural tumors were further divided into G-CIMP (glioma CpG-island methylator phenotype) or non-G-CIMP. **, p < 0.01. ****, p < 0.0001. *****, p < 0.00001. Supplemental Figure S2. Targeting RBPJ induces BTIC apoptosis. A. 3691 BTICs were transduced with shCONT, shRBPJ-1, or shRBPJ-2. Lysates were prepared and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. shRNA-mediated knockdown of RBPJ was associated with increased cleaved (activated) PARP. B. 3691 BTICs were transduced with shCONT, shRBPJ-1, or shRBPJ-2. Apoptosis measured by Annexin V staining. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (two- way ANOVA; **, p < 0.01; n = 3). Supplemental Figure S3. Targeting RBPJ does not affect non-BTIC proliferation. Non-BTICs (Top, 3691; Bottom, 4121) were transduced with shCONT, shRBPJ-1, or shRBPJ-2. Cell proliferation was measured by CellTiter-Glo. 42 Xie et al. Supplemental Figure S4. RBPJ induces transcriptional profiles in BTICs distinct from Notch activation. A. In parallel experiments, 3691 BTICs were either treated with DAPT (at either 5 μM or 10 μM) vs. vehicle control (DMSO) or transduced with shRBPJ vs. shCONT. RNA-Seq was performed and the results displayed as a heat map with normalization to the relevant control. -

Hormonal Regulation of Oligodendrogenesis I: Effects Across the Lifespan

biomolecules Review Hormonal Regulation of Oligodendrogenesis I: Effects across the Lifespan Kimberly L. P. Long 1,*,†,‡ , Jocelyn M. Breton 1,‡,§ , Matthew K. Barraza 2 , Olga S. Perloff 3 and Daniela Kaufer 1,4,5 1 Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA; [email protected] (J.M.B.); [email protected] (D.K.) 2 Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA; [email protected] 3 Memory and Aging Center, Department of Neurology, University of California, San Francisco, CA 94143, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 5 Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, Toronto, ON M5G 1M1, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected] † Current address: Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of California, San Francisco, CA 94143, USA. ‡ These authors contributed equally to this work. § Current address: Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027, USA. Abstract: The brain’s capacity to respond to changing environments via hormonal signaling is critical to fine-tuned function. An emerging body of literature highlights a role for myelin plasticity as a prominent type of experience-dependent plasticity in the adult brain. Myelin plasticity is driven by oligodendrocytes (OLs) and their precursor cells (OPCs). OPC differentiation regulates the trajectory of myelin production throughout development, and importantly, OPCs maintain the ability to proliferate and generate new OLs throughout adulthood. The process of oligodendrogenesis, Citation: Long, K.L.P.; Breton, J.M.; the‘creation of new OLs, can be dramatically influenced during early development and in adulthood Barraza, M.K.; Perloff, O.S.; Kaufer, D. -

Supplemental Data Olig2-Regulated Lineage-Restricted Pathway Controls Replication Competence in Neural Stem Cells and Malignant

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Caltech Authors Neuron, Volume 53 Supplemental Data Olig2-Regulated Lineage-Restricted Pathway Controls Replication Competence in Neural Stem Cells and Malignant Glioma Keith L. Ligon, Emmanuelle Huillard, Shwetal Mehta, Santosh Kesari, Hongye Liu, John A. Alberta, Robert M. Bachoo, Michael Kane, David N. Louis, Ronald A. DePinho, David J. Anderson, Charles D. Stiles, and David H. Rowitch Figure S1. Olig1/2+/- Ink4a/Arf-/-EGFRvIII Gliomas Express Characteristic Morphologic and Immunophenotypic Features of Human Malignant Gliomas (A) Tumors exhibit dense cellularity and atypia. (B) Characteristic infiltration of host SVZ stem cell niche. (C) Although occasional tumors exhibited pseudopalisading necrosis (n, arrowhead) and hemorrhage (h, arrowhead) similar to human GBM (Astrocytoma WHO Grade IV), most tumors lacked these features. (D) IHC for hEGFR highlights hallmark feature of human gliomas, including perivascular (pv) and subpial (sp) accumulation of tumor cells, (E) striking white matter tropism of tumor cells in corpus callosum (cc), and (F) distant single cell infiltration of cerebellar white matter (wm, arrows). (G-J) Immunohistochemical markers characteristic of human tumors (Gfap, Olig2, Olig1, Nestin) are present. (K and L) Weak staining for the early neuronal marker TuJ1 and absence of the differentiated neuronal marker, NeuN similar to human glioma and consistent with heterogeneous lines of partial differentiation. Figure S2. Olig1/2+/- Ink4a/Arf-/-EGFRvIII Neurospheres Are Multipotent and Olig1/2-/- Ink4a/Arf-/-EGFRvIII Neurospheres Are Bipotent Olig1/2+/- or Olig1/2-/- Ink4a/Arf-/-EGFRvIII neurospheres were allowed to differentiate for 6 days in medium without EGF. -

Transcription Factors Define the Neuroanatomical Organization Of

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 14 May 2013 NEUROANATOMY doi: 10.3389/fnana.2013.00007 Transcription factors define the neuroanatomical organization of the medullary reticular formation Paul A. Gray * Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA Edited by: The medullary reticular formation contains large populations of inadequately described, Kathleen S. Rockland, MIT, USA excitatory interneurons that have been implicated in multiple homeostatic behaviors Reviewed by: including breathing, viserosensory processing, vascular tone, and pain. Many hindbrain Joan S. Baizer, University of Buffalo, nuclei show a highly stereotyped pattern of localization across vertebrates suggesting USA Ruth Stornetta, University of a strong underlying genetic organization. Whether this is true for neurons within Virginia, USA the reticular regions of hindbrain is unknown. Hindbrain neurons are derived from *Correspondence: distinct developmental progenitor domains each of which expresses distinct patterns of Paul A. Gray, Department of transcription factors (TFs). These neuronal populations have distinct characteristics such Anatomy and Neurobiology, as transmitter identity, migration, and connectivity suggesting developmentally expressed Washington University School of Medicine, Box 8108, 660 S. Euclid TFs might identify unique subpopulations of neurons within the reticular formation. A Ave., St. Louis, MO 63110, USA. fate-mapping strategy using perinatal expression of reporter genes within Atoh1, Dbx1, e-mail: [email protected] Lmx1b,andPtf1a transgenic mice coupled with immunohistochemistry (IHC) and in situ hybridization (ISH) were used to address the developmental organization of a large subset of reticular formation glutamatergic neurons. All hindbrain lineages have relatively large populations that extend the entire length of the hindbrain. Importantly, the location of neurons within each lineage was highly constrained. -

Embryonic Development of the Hypothalamic Feeding Circuitry: Transcriptional, Nutritional, and Hormonal Influences

Minireview Embryonic development of the hypothalamic feeding circuitry: Transcriptional, nutritional, and hormonal influences Harry MacKay*, Alfonso Abizaid ABSTRACT Background: Embryonic neurogenesis and differentiation in the hypothalamic feeding circuitry is under the control of a variety of diffused morphogens and intrinsic transcription factors, leading to the unique structural and functional characteristics of each nucleus. Scope of review: The transcriptional regulation of the development of feeding neuroendocrine systems during the period of embryonic neurogenesis and differentiation will be reviewed here, with a special emphasis on genetic and environmental manipulations that yield an adverse metabolic phenotype. Major conclusions: Emerging data suggest that developmental mechanisms can be perturbed not only by genetic manipulation, but also by manipulations to maternal nutrition during the gestational period, leading to long-lasting behavioral, neurobiological, and metabolic conse- quences. Leptin is neurotrophic in the embryonic brain, and given that it varies in proportion to maternal energy balance, may mediate these effects through an interaction with the mechanisms of hypothalamic development. Ó 2014 The Authors. Published by Elsevier GmbH. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). Keywords Leptin; Developmental origins of health and disease; Hypothalamic neurogenesis; Basic helix-loop helix Homeostatic control over feeding and energy balance is regulated in 1. NEUROGENESIS AND DIFFERENTIATION IN THE large part by the hypothalamus, specifically a network of nuclei DEVELOPING HYPOTHALAMUS comprising the arcuate nucleus (ARC), ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH), paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and the lateral hypothalamus Neural tube development can be divided into stages, the first of which (LH). -

Table SII. Significantly Differentially Expressed Mrnas of GSE23558 Data Series with the Criteria of Adjusted P<0.05 And

Table SII. Significantly differentially expressed mRNAs of GSE23558 data series with the criteria of adjusted P<0.05 and logFC>1.5. Probe ID Adjusted P-value logFC Gene symbol Gene title A_23_P157793 1.52x10-5 6.91 CA9 carbonic anhydrase 9 A_23_P161698 1.14x10-4 5.86 MMP3 matrix metallopeptidase 3 A_23_P25150 1.49x10-9 5.67 HOXC9 homeobox C9 A_23_P13094 3.26x10-4 5.56 MMP10 matrix metallopeptidase 10 A_23_P48570 2.36x10-5 5.48 DHRS2 dehydrogenase A_23_P125278 3.03x10-3 5.40 CXCL11 C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 11 A_23_P321501 1.63x10-5 5.38 DHRS2 dehydrogenase A_23_P431388 2.27x10-6 5.33 SPOCD1 SPOC domain containing 1 A_24_P20607 5.13x10-4 5.32 CXCL11 C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 11 A_24_P11061 3.70x10-3 5.30 CSAG1 chondrosarcoma associated gene 1 A_23_P87700 1.03x10-4 5.25 MFAP5 microfibrillar associated protein 5 A_23_P150979 1.81x10-2 5.25 MUCL1 mucin like 1 A_23_P1691 2.71x10-8 5.12 MMP1 matrix metallopeptidase 1 A_23_P350005 2.53x10-4 5.12 TRIML2 tripartite motif family like 2 A_24_P303091 1.23x10-3 4.99 CXCL10 C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 A_24_P923612 1.60x10-5 4.95 PTHLH parathyroid hormone like hormone A_23_P7313 6.03x10-5 4.94 SPP1 secreted phosphoprotein 1 A_23_P122924 2.45x10-8 4.93 INHBA inhibin A subunit A_32_P155460 6.56x10-3 4.91 PICSAR P38 inhibited cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma associated lincRNA A_24_P686965 8.75x10-7 4.82 SH2D5 SH2 domain containing 5 A_23_P105475 7.74x10-3 4.70 SLCO1B3 solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 1B3 A_24_P85099 4.82x10-5 4.67 HMGA2 high mobility group AT-hook 2 A_24_P101651 -

Molecular Signatures Differentiate Immune States in Type 1 Diabetes Families

Page 1 of 65 Diabetes Molecular signatures differentiate immune states in Type 1 diabetes families Yi-Guang Chen1, Susanne M. Cabrera1, Shuang Jia1, Mary L. Kaldunski1, Joanna Kramer1, Sami Cheong2, Rhonda Geoffrey1, Mark F. Roethle1, Jeffrey E. Woodliff3, Carla J. Greenbaum4, Xujing Wang5, and Martin J. Hessner1 1The Max McGee National Research Center for Juvenile Diabetes, Children's Research Institute of Children's Hospital of Wisconsin, and Department of Pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin Milwaukee, WI 53226, USA. 2The Department of Mathematical Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI 53211, USA. 3Flow Cytometry & Cell Separation Facility, Bindley Bioscience Center, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA. 4Diabetes Research Program, Benaroya Research Institute, Seattle, WA, 98101, USA. 5Systems Biology Center, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20824, USA. Corresponding author: Martin J. Hessner, Ph.D., The Department of Pediatrics, The Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI 53226, USA Tel: 011-1-414-955-4496; Fax: 011-1-414-955-6663; E-mail: [email protected]. Running title: Innate Inflammation in T1D Families Word count: 3999 Number of Tables: 1 Number of Figures: 7 1 For Peer Review Only Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online April 23, 2014 Diabetes Page 2 of 65 ABSTRACT Mechanisms associated with Type 1 diabetes (T1D) development remain incompletely defined. Employing a sensitive array-based bioassay where patient plasma is used to induce transcriptional responses in healthy leukocytes, we previously reported disease-specific, partially IL-1 dependent, signatures associated with pre and recent onset (RO) T1D relative to unrelated healthy controls (uHC). -

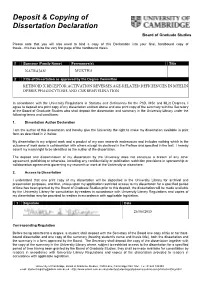

Deposit & Copying of Dissertation Declaration

Deposit & Copying of Dissertation Declaration Board of Graduate Studies Please note that you will also need to bind a copy of this Declaration into your final, hardbound copy of thesis - this has to be the very first page of the hardbound thesis. 1 Surname (Family Name) Forenames(s) Title NATRAJAN MUKTHA 2 Title of Dissertation as approved by the Degree Committee RETINOID X RECEPTOR ACTIVATION REVERSES AGE-RELATED DEFICIENCIES IN MYELIN DEBRIS PHAGOCYTOSIS AND CNS REMYELINATION In accordance with the University Regulations in Statutes and Ordinances for the PhD, MSc and MLitt Degrees, I agree to deposit one print copy of my dissertation entitled above and one print copy of the summary with the Secretary of the Board of Graduate Studies who shall deposit the dissertation and summary in the University Library under the following terms and conditions: 1. Dissertation Author Declaration I am the author of this dissertation and hereby give the University the right to make my dissertation available in print form as described in 2. below. My dissertation is my original work and a product of my own research endeavours and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration with others except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I hereby assert my moral right to be identified as the author of the dissertation. The deposit and dissemination of my dissertation by the University does not constitute a breach of any other agreement, publishing or otherwise, including any confidentiality or publication restriction provisions in sponsorship or collaboration agreements governing my research or work at the University or elsewhere. -

Deficits in Human Trisomy 21 Ipscs and Neurons

Deficits in human trisomy 21 iPSCs and neurons Jason P. Weicka,1, Dustie L. Helda, George F. Bonadurer IIIa, Matthew E. Doersa, Yan Liua, Chelsie Maguirea, Aaron Clarka, Joshua A. Knackerta, Katharine Molinaroloa, Michael Mussera, Lin Yaoa, Yingnan Yina, Jianfeng Lua, Xiaoqing Zhanga, Su-Chun Zhanga,b,c,d, and Anita Bhattacharyyaa,2 aWaisman Center, bNeuroscience Training Program, and Departments of cNeuroscience and dNeurology, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53705 Edited by Fred H. Gage, The Salk Institute for Biological Studies, San Diego, CA, and approved May 1, 2013 (received for review September 26, 2012) Down syndrome (trisomy 21) is the most common genetic cause of uniparental disomy (or isodisomy), which is often associated with intellectual disability, but the precise molecular mechanisms un- trisomy rescue (Fig. 1D). Short tandem repeats at various loci derlying impaired cognition remain unclear. Elucidation of these indicated that the Ts21 and euploid lines were isogenic other than mechanisms has been hindered by the lack of a model system that the presence of Ts21 (Fig. 1E). To increase statistical power, contains full trisomy of chromosome 21 (Ts21) in a human genome fibroblasts from a second DS individual were reprogrammed us- that enables normal gene regulation. To overcome this limitation, we ing Sendai virus (12), an RNA virus, which yielded another Ts21 created Ts21-induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from two sets of iPSC line (Fig. 1C). All iPSC clones were named according to Ts21 human fibroblasts. One of the fibroblast lines had low level standardized naming procedures (Fig. 1F) (13) and used in all mosaicism for Ts21 and yielded Ts21 iPSCs and an isogenic control experiments. -

Aberrant Dna Methylation in Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

ABERRANT DNA METHYLATION IN HUMAN NON-SMALL CELL LUNG CANCER DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Romulo Martin Brena, B.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by: Dr. Christoph Plass, Adviser Dr. Thomas J. Rosol ____________________________________ Dr. Michael C. Ostrowski Adviser Graduate Program in Molecular Genetics Dr. Gregory A. Otterson Dr. Laura J. Rush ABSTRACT Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. Given its impact on human health, extensive research is being conducted in an effort to reduce the global lung cancer death toll. Specifically, much interest has been placed on the development of biomarkers and the discovery of novel prognostic factors. Over the past 2 decades it has become evident that the cancer genome is not only affected by genetic abnormalities, such as mutations, deletions and chromosomal rearrangements, but also by epigenetic changes which, together, contribute to the deregulation of transcription profiles. Epigenetic changes are defined as heritable lesions to the DNA affecting gene expression without altering the primary DNA sequence. These lesions typically involve a genomewide reduction in 5-methylcytosine, increased DNA methylation in gene promoter sequences and substitutions in histone tail modifications. Epigenetic changes have been shown to interact with one another, resulting in genomic instability, silencing of tumor suppressor genes, activation of oncogenes and derepression of transposable elements. As opposed to the irreversible nature of genetic lesions, epigenetic lesions can be reversed. Because of their reversibility, epigenetic alterations have become an attractive target for new therapies, which has resulted in the development of new anticancer compounds, several of which are currently in clinical trials.