Medicines Optimisation: a Pharmacist’S Contribution to Delivery and Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Literacy and ESOL) Certificate Additional Diploma in Teaching Mathematics (Numeracy) Certificate Additional Diploma in Teaching Disabled Learners

Certificate Additional Diploma in Teaching English (Literacy and ESOL) Certificate Additional Diploma in Teaching Mathematics (Numeracy) Certificate Additional Diploma in Teaching Disabled Learners Programme Specification 2014/15 Cohort PROGRAMME SPECIFICATION – Certificate Additional Diplomas in Teaching Course Record Information Name and level of Certificate Additional Diploma in Teaching English: Final and Intermediate Awards Literacy & ESOL Certificate Additional in Teaching Mathematics: Numeracy Certificate Additional Diploma in Teaching Disabled Learners Awarding Body/Institution University of Westminster Status of awarding Listed body body/institution Location of Delivery and University of Westminster Education Consortium teaching institutions Colleges: • Amersham & Wycombe College • City Literary Institute • Ealing, Hammersmith and West London College • Harrow College • Newham College • Richmond Adult Community College. • Uxbridge College • West Thames College Mode of Study Part-time, in-service UW Course Code BWBSADT Amersham & Wycombe College City Literary Institute Ealing, Hammersmith and West London College Harrow College Newham College Uxbridge College West Thames College JACS Code X141 Teacher Training UCAS Code Not applicable QAA Subject Benchmarking Education Studies Group Professional Body Accreditation Education and Training Foundation Institute for Learning Date of course validation/review 1 July 2014 Date of Programme February 2014 Specification Admissions Requirements Normally those applying to join the Course will: 1) be regularly employed in the education or training of participants in the Lifelong Learning Sector for normally at least an average of 3 hours per week or 100 hours a year in an approved placement, with relevant Literacy and ESOL or Numeracy or Disability teaching practice; 2) have responsibility for the group that they are teaching for planning and assessing the learning. -

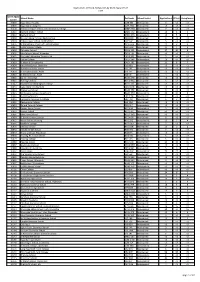

Updated 2011/12 Allocation/Maximum Contract Value

Skills Funding Agency Allocations 2011/12 as at 20 April 2012 Provider Provider Name Adult Skills 16-18 Adult Formal Additional 19+ Joint Employer *ESF Total UPIN Budget Apprenticeship Safeguarded First Step Learning Support Discretionary Investment Simplificatio 2011/12 2011/12 s 2011/12 Learning 2011/12 2011/12 (former Learner Support Programme n Pilot 2011/12 ALR ALS) 2011/12 2011/12 2011/12 105000 BARNFIELD COLLEGE £6,939,969 £1,400,991 £198,865 £0 £916,436 £440,173 £0 £0 £144,960 £10,041,394 105008 NACRO £566,737 £537,652 £0 £0 £0 £0 £0 £0 £868,461 £1,972,850 105010 NORTH HERTFORDSHIRE COLLEGE £9,729,688 £3,354,454 £0 £0 £595,579 £255,267 £0 £0 £954,750 £14,889,738 105017 CENTRAL BEDFORDSHIRE COLLEGE £3,469,386 £336,319 £40,016 £0 £284,133 £210,347 £0 £0 £0 £4,340,201 105019 AMERSHAM AND WYCOMBE COLLEGE £3,957,472 £324,469 £3,859 £28,698 £688,633 £117,960 £18,538 £0 £411,650 £5,551,279 105023 BERKSHIRE COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE £885,269 £0 £5,002 £0 £43,052 £86,366 £0 £0 £0 £1,019,689 105024 BRACKNELL AND WOKINGHAM COLLEGE £2,836,426 £652,651 £365,732 £0 £146,429 £89,755 £0 £0 £0 £4,090,993 105028 THE HENLEY COLLEGE £595,279 £343,619 £41,079 £0 £117,132 £15,453 £0 £0 £0 £1,112,562 105032 NG BAILEY LIMITED £67,560 £443,136 £0 £0 £0 £0 £0 £0 £0 £510,696 105037 SPAN TRAINING & DEVELOPMENT LIMITED £315,173 £806,486 £0 £0 £0 £0 £0 £0 £0 £1,121,659 105041 PERTEMPS LEARNING AND EDUCATION ALLIANCE LIMITED £1,077,159 £27,811 £0 £0 £0 £0 £0 £0 £583,335 £1,688,305 105044 UK TRAINING & DEVELOPMENT LIMITED £459,558 £806,961 £0 £0 £0 £0 £0 £0 £0 -

The Education (Listed Bodies) (Wales) Order 2007

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. WELSH STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2007 No. 2794 (W.234) EDUCATION, WALES The Education (Listed Bodies) (Wales) Order 2007 Made - - - - 19 September 2007 Coming into force - - 1 October 2007 The Welsh Ministers, in exercise of the powers conferred upon the Secretary of State by sections 216(2) and 232(5) of the Education Reform Act 1988(1) and now vested in them(2), make the following Order: Title, commencement and application 1.—(1) The title of this Order is the Education (Listed Bodies) (Wales) Order 2007 and it comes into force on 1 October 2007. (2) This Order applies to Wales. Listed Bodies 2. The bodies that are specified in the Schedule to this Order comprise all those bodies that appear to the Welsh Ministers to fall for the time being within section 216(3) of the Education Reform Act 1988. Revocation 3. The Education (Listed Bodies) (Wales) Order 2004(3) and the Education (Listed Bodies) (Wales) (Amendment) Order 2005 are revoked(4). (1) 1988 c. 40. (2) By virtue of the National Assembly for Wales (Transfer of Functions) Order 1999 (SI 1999/672), and paragraph 30(1) and (2)(a) of Schedule 11 to the Government of Wales Act 2006. (3) SI 2004/3095. (4) SI 2005/1648. Document Generated: 2017-08-03 Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. Jane E. -

Morley College London PROGRAMME

LEADING LEARNING FOR LIFE IN CHANGING TIMES Conference Programme 3 May 2018 #LeadingAdultEd Conference WELCOME to Morley College London PROGRAMME All events are located in Emma Cons Hall except where noted 9:30 Registration, networking and refreshments 10:00 Welcome Dr Andrew Gower, Morley College London SESSION 1 – PART 1 I am delighted you have 10.10 Policy context and leadership joined us for this conference. Dr Sue Pember OBE, HOLEX We are very pleased to 10:25 Leading in post-market conditions have you with us. Prof Martin Doel CBE, UCL Institute of Education 10:45 Q&A and panel discussion Morley has been part of the learning landscape of London for almost 130 years. Our core purpose remains true to the founding mission 11:25 Networking and refreshments of the College: celebrating the transformative power of learning for learners, their families, and their communities. As an Institute of Adult SESSION 1 – PART 2 Learning we recognise the need to adapt and evolve to continue to meet the changing learning needs of the communities we serve, and I am 11:40 Impact and devolution: implications for policy especially grateful to my colleague, Dragana Ramsden, Head of Morley’s and practice in the UK Centre for Community Learning and Engagement, for being the driving Mark Ravenhall, Learning and Work Institute force behind the event today. 12:05 Q&A and discussion This conference provides a privileged opportunity to bring together 12:35 Lunch the experience and expertise of presenters and delegates to discuss Location: Holst Room the challenges and opportunities leaders in adult education face in responding to drivers for change – whether in life, at work, or through SESSION 2 – A CHOICE BETWEEN policy. -

Association of Colleges 27/03/2015 09/04/2015 Barking and Dagenham

Migration Date Organisation Name Actual Delivery Date (RFCA Date) Association of Colleges 27/03/2015 09/04/2015 Barking and Dagenham College 24/07/2014 31/10/2014 Barnet and Southgate College (Barnet Campus) 27/06/2014 04/11/2014 Barnet and Southgate College (Southgate Campus) * 22/10/2014 11/11/2014 Bexley College 21/08/2014 28/08/2014 British Universities Film & Video Council Not Yet Delivered Not Yet Migrated Bromley College of Further and Higher Education (Orpington Campus) 24/07/2014 19/11/2014 Bromley College of Further and Higher Education (Bromley Campus) 11/11/2014 20/11/2014 Brooke House Sixth Form College 26/08/2014 18/09/2014 Cancer Research UK 29/05/2014 13/03/2014 Capel Manor College 27/06/2014 08/10/2014 Carshalton College 24/07/2014 10/09/2014 Christ the King Sixth Form College 27/06/2014 10/09/2014 Christ the King Sixth Form College (St Mary's Sixth Form College) 28/10/2014 16/12/2014 City and Islington College (Centre for Health, Social and Child Care) 24/07/2014 29/08/2014 City of Westminster College 23/12/2014 02/04/2015 City University * 22/10/2014 21/10/2014 College of North West London 27/06/2014 07/10/2014 Coulsdon Sixth Form College 23/12/2014 13/01/2015 Courtauld Institute of Art 18/12/2014 19/01/2015 Croydon College (Primary) 11/11/2014 13/01/2015 Croydon College 19/11/2014 13/01/2015 Ealing, Hammersmith and West London College (Ealing Campus) 03/10/2014 15/10/2014 Ealing, Hammersmith and West London College (Hammersmith Campus) 03/10/2014 14/10/2014 East Berkshire College 04/07/2014 21/08/2014 Esher College -

Module Record Only 1996/97

Module Record Only 1996/97 Module Record Field Field Description Field Field Field Nr. Abbrev'n Length Type 1 Record type indicator RECID 5 Numeric 2 HESA institution identifier INSTID 4 Alphanumeric 3 Campus identifier CAMPID 1 Alphanumeric 4 Module title MTITLE 80 Alphanumeric 5 Module identifier MODID 12 Alphanumeric 6 Proportion of FTE FTE 5 Numeric 7 Proportion not taught by this institution PCOLAB 5 Numeric 8 Credit transfer scheme CRDTSCM 1 Numeric 9 Credit value of module CRDTPTS 3 Numeric 10 Level of credit points LEVLPTS 1 Numeric 11 Module length MODLEN 2 Numeric 12 Cost centre 1 COSTCN01 2 Numeric 13 Subject area of study 1 SBJ01 3 Alphanumeric 14 Proportion of subject 1 SBJPER01 5 Numeric 15 Cost centre 2 COSTCN02 2 Numeric 16 Subject area of study 2 SBJ02 3 Alphanumeric 17 Proportion of subject 2 SBJPER02 5 Numeric 18 Not used VLEVEL 2 Numeric 19 Other institution providing teaching 1 TINST1 7 Alphanumeric 20 Guided learning hours GLHRS 5 Alphanumeric t Required for December return Field Field Description Field Field Field Nr. Abbrev'n Length Type 1 Record type indicator RECID 5 Numeric STATUS Compulsory. TIMESCALE Required in the July data collection only. VALID ENTRIES 96011 Combined student/course record. 96012 Student record. 96013 Module record. 96014 Aggregate record of non-credit-bearing courses. 96016 First destination supplement. 96017 Trainee teacher information supplement (Scotland). 96019 HE in FE Colleges. 96021 Staff individualised record. 96022 Staff aggregate record. 96023 Staff load record. 96024 Research output record. 96031 Finance statistics return. 96032 Estate record. 96111 Students on low credit-bearing courses - English and Welsh institutions only (Combined record). -

Funding Values for Grant and Procured Providers

Greater London Authority Adult Education Budget Allocation Grant Values 2020 to 2021 As at 1 August 2020 Version 1.0 UKPRN Provider Name Total GLA AEB funding value (2020/21) 10004927 ACTIVATE LEARNING £107,836 10000143 BARKING & DAGENHAM LONDON BOROUGH COUNCIL £1,679,207 10000528 BARKING AND DAGENHAM COLLEGE £5,996,283 10000533 BARNET & SOUTHGATE COLLEGE £13,285,990 10000560 BASINGSTOKE COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY £553,104 10001465 BATH COLLEGE £127,308 10000610 BEDFORD COLLEGE £369,070 10000146 BEXLEY LONDON BOROUGH COUNCIL £2,102,127 10000863 BRENT LONDON BOROUGH COUNCIL £3,062,001 10000878 BRIDGWATER AND TAUNTON COLLEGE £247,601 10000948 BROMLEY COLLEGE OF FURTHER AND HIGHER EDUCATION £6,422,450 10003987 BROMLEY LONDON BOROUGH COUNCIL £1,629,632 10000950 BROOKLANDS COLLEGE £110,746 10000473 BUCKINGHAMSHIRE COLLEGE GROUP £546,875 10001116 CAMBRIDGE REGIONAL COLLEGE £602,322 10003988 CAMDEN LONDON BOROUGH COUNCIL £1,275,584 10001148 CAPEL MANOR COLLEGE £1,963,131 10001467 CITY OF BRISTOL COLLEGE £293,395 10008915 COMMON COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF LONDON £713,615 10001778 CROYDON COLLEGE £3,627,156 10003989 CROYDON LONDON BOROUGH COUNCIL £4,335,989 10001919 DERBY COLLEGE GROUP £698,658 10004695 DN COLLEGES GROUP £99,923 10009206 EALING LONDON BOROUGH COUNCIL £827,145 10002094 EALING, HAMMERSMITH & WEST LONDON COLLEGE £8,065,215 10002130 EAST SURREY COLLEGE £882,583 10002923 EAST SUSSEX COLLEGE GROUP £390,066 10002143 EASTLEIGH COLLEGE £3,643,450 10006570 EKC GROUP £463,805 10002638 GATESHEAD COLLEGE £561,385 10002696 GLOUCESTERSHIRE COLLEGE £207,780 -

237 Colleges in England.Pdf (PDF,196.15

This is a list of the formal names of the Corporations which operate as colleges in England, as at 3 February 2021 Some Corporations might be referred to colloquially under an abbreviated form of the below College Type Region LEA Abingdon and Witney College GFEC SE Oxfordshire Activate Learning GFEC SE Oxfordshire / Bracknell Forest / Surrey Ada, National College for Digital Skills GFEC GL Aquinas College SFC NW Stockport Askham Bryan College AHC YH York Barking and Dagenham College GFEC GL Barking and Dagenham Barnet and Southgate College GFEC GL Barnet / Enfield Barnsley College GFEC YH Barnsley Barton Peveril College SFC SE Hampshire Basingstoke College of Technology GFEC SE Hampshire Bath College GFEC SW Bath and North East Somerset Berkshire College of Agriculture AHC SE Windsor and Maidenhead Bexhill College SFC SE East Sussex Birmingham Metropolitan College GFEC WM Birmingham Bishop Auckland College GFEC NE Durham Bishop Burton College AHC YH East Riding of Yorkshire Blackburn College GFEC NW Blackburn with Darwen Blackpool and The Fylde College GFEC NW Blackpool Blackpool Sixth Form College SFC NW Blackpool Bolton College FE NW Bolton Bolton Sixth Form College SFC NW Bolton Boston College GFEC EM Lincolnshire Bournemouth & Poole College GFEC SW Poole Bradford College GFEC YH Bradford Bridgwater and Taunton College GFEC SW Somerset Brighton, Hove and Sussex Sixth Form College SFC SE Brighton and Hove Brockenhurst College GFEC SE Hampshire Brooklands College GFEC SE Surrey Buckinghamshire College Group GFEC SE Buckinghamshire Burnley College GFEC NW Lancashire Burton and South Derbyshire College GFEC WM Staffordshire Bury College GFEC NW Bury Calderdale College GFEC YH Calderdale Cambridge Regional College GFEC E Cambridgeshire Capel Manor College AHC GL Enfield Capital City College Group (CCCG) GFEC GL Westminster / Islington / Haringey Cardinal Newman College SFC NW Lancashire Carmel College SFC NW St. -

Central London Area Review College Annex

Central London Area Review College annex February 2017 Contents1 City and Islington College 3 City of Westminster College 4 The College of Haringey, Enfield and North East London 5 Hackney Community College 6 Kensington and Chelsea College 7 Lambeth College 8 Lewisham Southwark College 10 South Thames College 11 Tower Hamlets College 12 Westminster Kingsway College 14 The Brooke House Sixth Form College 15 Christ The King Sixth Form College 16 St Charles Catholic Sixth Form College 17 St Francis Xavier Sixth Form College 18 Morley College 19 The City Literary Institute 20 The Working Men’s College 21 1 Please note that the information on the colleges included in this annex relates to the point at which the review was undertaken. No updates have been made to reflect subsequent developments or appointments since the completion of the review. 2 City and Islington College2 Type: General further education college Location: City and Islington College is a large college which operates from 5 main sites and over 25 satellite sites and community venues in the London Borough of Islington Local Enterprise Partnership: Greater London Authority Principal: Sir Frank McLoughlin CBE Corporation Chair: Alastair Da Costa Main offer includes: A range of curriculum areas that reflect the LEP’s priorities which include professional, scientific and technical areas, followed by administration, health, social work, IT and finance Technical qualifications are predominantly BTEC but there are some City and Guild courses in plumbing and engineering and Institute -

2017 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2017 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <3 <3 10006 Ysgol Gyfun Llangefni LL77 7NG Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 7 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 13 6 5 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 19 5 5 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 4 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 5 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 11 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 17 4 3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 27 10 8 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent 5 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 10 <3 <3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 21 8 7 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent <3 <3 <3 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 4 <3 <3 10040 Garth Hill College RG42 2AD Maintained <3 <3 <3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 3 <3 <3 10042 Bracknell and Wokingham College RG12 1DJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained 3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU -

Part 2 – Confidential Facts and Advice

Appendix A – Project List Successful Projects GLA capital Proj ect ti tl e Organisation contribution IT enabled S E ND provision New City College £300,000.00 Developing Invitational Centres London Borough of Lewisham Regeneration Unit £300,000.00 Outstanding Digital E xperience for Learners The City Literary Institute £219,714.00 Expanding Adult Education Digitally in Communities RB K ingston Upon Thames (K ingston Adult E ducation) £94,000.00 Digital Inclusion at WAES City of Westminster Council (WAES) £75,500.00 E xpansion of The Right Course LTE Group - Novus £108,376.00 Inspiring spaces: lecture and screening auditorium The City Literary Institute £231,516.00 Upgrading SEND facilities Barking & Dagenham College £300,000.00 Improving Learner E ngagement S utton College £69,450.00 Digital media for construction proposal Waltham Forest College (RH Architects) £300,000.00 Investing in Sculpture Skills Morley College London £80,500.00 MITSkills Limited Brentford Capital Bid 2019 MITSkills Limited £35,000.00 Building Infrastructure S kills for the F uture LONDON SKILLS & DEVELOP MENT NETWORK £65,000.00 British Academy of J ewellery British Academy of J ewellery £42,862.00 Design Innovation Room LB Redbridge - Redbridge Institute Community Learning and S kills £25,000.00 S ports facilities for sixth form students St Charles Sixth Form College £48,000.00 P erforming Arts S pace and S E ND Training K itchen S outh Thames Colleges Group £222,500.00 Outreach IT E ast London Advanced Technology Training (E LATT) £53,702.00 Improving Learning through -

Committee Ref

COMMITTEE REF: OSB/03/16 NOTICE OF MEETING OVERVIEW AND SCRUTINY BOARD Date : THURSDAY, 24 MARCH 2016 Time : 18:00 Place : COUNCIL CHAMBER TOWN HALL, LUTON Councillors: M. DOLLING (CHAIR) HOPKINS BAKER (VICE-CHAIR) KEENS RAFIQ (VICE-CHAIR) MALIK FRANKS MOLES GREEN RODEN Quorum: 3 elected Members Contact Officer: EUNICE LEWIS (01582 54 7149) EMERGENCY EVACUATION PROCEDURE Committee Rooms 1, 2, 4 & Council Chamber: Turn left, follow the green emergency exit signs to the main town hall entrance and proceed to the assembly point at St George's Square. Committee Room 3: Proceed straight ahead through the double doors, follow the green emergency exit signs to the main Town Hall entrance and proceed to the assembly point at St George's Square. Page 1 of 118 AGENDA Agenda Subject Page Item No. 1 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 2 MINUTES 2.1 17th February 2016 - Public Minutes 4 - 7 2.2 - 2nd February - To Follow 2.3 - 17th February - Private Minutes (Members Only) 3 CHAIR'S UPDATE Chair to report on issues since the last meeting. 4 DISCLOSURES OF INTEREST Members are reminded that they must disclose both the existence and nature of any disclosable pecuniary interest and any personal interest that they have in any matter to be considered at the meeting unless the interest is a sensitive interest in which event they need not disclose the nature of the interest. A member with a disclosable pecuniary interest must not further participate in any discussion of, vote on, or take any executive steps in relation to the item of business. A member with a personal interest, which a member of the public with knowledge of the relevant facts would reasonably regard as so significant that it is likely to prejudice the member’s judgment of the public interest, must similarly not participate in any discussion of, vote on, or take any executive steps in relation to the item of business.