Women and Wwi Some Images

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19 to the 21 St Centuries

Centre for British Studies International Conference Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19th to the 21st centuries Belgrade, January 26-27, 2018 Conference: Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19th to the 21st centuries Belgrade, January 26-27, 2018 P R O G R A M M E Venue: Faculty of Political Science of the University of Belgrade, Jove Ilića 165 Friday, January 26, 2018 12.00–12.50 Opening of the Conference: H. E. Denis Keefe, CMG, HM Ambassador to Serbia Prof. Dragan Simić, Dean of the Faculty of Political Science, Belgrade Prof. em. Vukašin Pavlović, President of the Council of the Centre for British Studies, FPS, UoB 13.00–14.30 Panel 1: Serbia, the UK, and Global World Chairperson: Dr. Spyros Economides, London School of Economics and Political Science Panellists: Sir John Randall, former Member of Parliament and Government Deputy Chief Whip British-Serbian Relations H. E. Amb. Branimir Filipović, Assistant Minister, MFA of Serbia British-Serbian Relations since 2000. A View from Serbia David Gowan, CMG, former ambassador of the UK to Serbia and Montenegro British-Serbian Relations since 2000. A View from Britain Prof. Christopher Coker, London School of Economics Britain and the Balkans in Global World 14.30–15.45 Lunch break 1 Conference: Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19th to the 21st centuries Belgrade, January 26-27, 2018 15.45–17.15 Panel 2: Diffi cult Legacies and New Opportunities Chairperson: Prof. Slobodan G. Markovich, Centre for British Studies, FPS, UoB Panellists: Dr. Spyros Economides, London School of Economics Legacy of UN Interventionism in British-Serbian Relations Prof. -

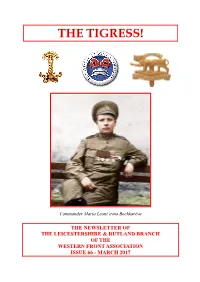

Issue 66 - March 2017 Editorial

THE TIGRESS! Commander Maria Leont’evna Bochkarëva THE NEWSLETTER OF THE LEICESTERSHIRE & RUTLAND BRANCH OF THE WESTERN FRONT ASSOCIATION ISSUE 66 - MARCH 2017 EDITORIAL Welcome again, Ladies and Gentlemen, to the latest edition of “The Tiger”, rechristened “The Tigress” for this special ladies edition! Despite whiling away many a youthful hour under a candlewick bedspread listening to Radio Luxembourg 208, I don’t seem to have much time these days to listen to the radio but I noticed that, on 8th March, Radio 3 dedicated its whole day’s playlist, in recognition of their bold and diverse contribution to music, to female composers one of whom being Elisabeth Lutyens, daughter of architect Edwin. Why did the BBC decide to do this? It was to celebrate International Women’s Day (IWD). I was reminded of the impending IWD last month when researching the remarkable exploits of Russian women in 1917 without whom the revolution may not have occurred exactly as it did 100 years ago. Their story will be recounted later in this Newsletter . The month of March itself could even be described as “Ladies Month” since its very flower, the daffodil, is also known as the birth flower, and its 31 days contain not only IWD (8th) but Lady Day or Annunciation Day (25th) and Mothering Sunday (26th). Militarily, of course, March was named after Mars, the Roman god of war whose month was Martius and from where originated the word martial. Another definition of March is “walk in a military manner with a regular measured tread”, a meaning which countless troops over the centuries learned as part of their basic training. -

Flora Sandes Born: 22

Flora Sandes BORN: 22. 01. 1876 About 80,000 women were employed NATIONALITY: English during World War I as nurses and orderlies at field hospitals. These were usually some distance away from the fighting. Only very PROFESSION: Nurse-turned-soldier few women entered active service in armies. in the Serbian Army Flora Sandes is one such example. DIED: 1955 (date unknown) The daughter of a clergyman, Flora Sandes grew up in the small Yorkshire town of Poppleton. She became a nurse and worked for the St John Ambulance and later worked for the First Aid When World War I began, Sandes was 38. She Nursing Yeomanry (FANY) in Britain. volunteered immediately for an ambulance unit in Serbia that was run by the Red Cross. In 1915, American female nurses carry gas masks with them as they walk through trenches in France. More the Serbian army retreated through the Albanian than 1,500 female nurses from the United States served in the forces during World War. mountains from the armies of Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria. Sandes became separated from her unit and was caught up in battle with a unit of As soon as she could, Sandes returned to Serbia. At the age of 64, Sandes returned to serve in the the Serbian Second Infantry Regiment. Picking She remained in the Serbian Army after the war Serbian forces – this time in World War II. She up a weapon to defend herself, she impressed ended. In June 1919, a special Act of Parliament was captured in uniform by the Germans and the company commander, Colonel Militch and in Serbia was passed to make Sandes the first taken to a military prison hospital. -

Chesterfield Wfa

CHESTERFIELD WFA Newsletter and Magazine issue 36 Patron –Sir Hew Strachan Welcome to Issue 36 - the December2018 FRSE FRHistS Newsletter and Magazine of Chesterfield President - Professor WFA. Peter Simkins MBE FRHistS Vice-Presidents Andre Colliot Professor John Bourne BA PhD FRHistS The Burgomaster of Ypres The Mayor of Albert Lt-Col Graham Parker OBE Professor Gary Sheffield BA MA PhD FRHistS Christopher Pugsley FRHistS Lord Richard Dannat GCB CBE MC DL th For our Meeting on Tuesday 4 December we welcome Roger Lee PhD jssc Dr Phylomena Badsey. Dr Badsey specialises in nursing during the First World War. She also maintains a broad Dr Jack Sheldon Interest in women and warfare, occupation and social www.westernfrontassociation.com change. Branch contacts Dr. Badsey`s presentation will be Tony Bolton (Chairman) "Auxiliary Hospitals and the role of Voluntary Aid anthony.bolton3@btinternet Detachment Nurses during the First World War" .com Mark Macartney The Branch meets at the Labour Club, Unity House, Saltergate, (Deputy Chairman) [email protected] Chesterfield S40 1NF on the first Tuesday of each month. There Jane Lovatt (Treasurer) is plenty of parking available on site and in the adjacent road. Grant Cullen Access to the car park is in Tennyson Road, however, which is (Secretary) [email protected] one way and cannot be accessed directly from Saltergate. Grant Cullen – Branch Secretary Facebook http://www.facebook.com/g roups/157662657604082/ http://www.wfachesterfield.com/ Western Front Association Chesterfield Branch – Meetings 2019 Meetings start at 7.30pm and take place at the Labour Club, Unity House, Saltergate, Chesterfield S40 1NF January 8th Jan.8th Note Date Change. -

AYESHA CONTEH, 8S the First World War

A VIRTUAL MUSEUM BY AYESHA CONTEH, 8S The First World war. All the facts and stories of the harrowing, long four year war. About the war - myths and truth. Yes, Women did not fight in the armed The First World War broke out in August forces of most nations in WW1, but 1914, killing over 9 million people and there were lots of women in a range of injuring over 21 million during 21 battles across the world. Fighting finally ceased roles including auxiliary roles in the on 11th November 1918 and the date has army as well as traditional nursing roles. since been commemorated as Some women were killed, some saw the Remembrance Day, in recognition of the trenches first-hand, and all of their scale of human lives lost in the conflict. roles were crucial to the war effort. A popular thought about the war is that women hardly contributed and that the war was fought and experienced by men, But The truth is surprisingly far from that. FLORA SANDES Officer of Royal Serbian Army, WW1. Born on January 22 1876, Flora Sandes was a British woman who served as an officer of the Royal Serbian Army and was the only British woman officially to serve as a soldier in WWI. She started off as a St. John Ambulance volunteer, and then travelled to the Kingdom of Serbia, where she was welcomed and went on to enroll in the Serbian army. Flora recalled how she "naturally drifted, in successive stages, from a nurse into a soldier. The soldiers seem to have taken it for granted that anyone who could ride and shoot, and I could do both, would be a soldier, in such a crisis." Where was WW1 fought? Did you know? When people remember the First World War in Britain today, That four million non white people from they usually pay respects by visiting local war memorials or different parts of the world were recruited visiting the graves of family members who were involved. -

WOBUL October 2018

Your local journal with news, past and future events and interesting articles 2 2 Palgrave Cinema – All The Money In The World, Saturday 13 October 3 Emma’s Jumble Sale, 27 October, Wortham Village Hall 4 Charity Fundraiser by Mike Bowen – Did You Jive in 55 – Sunday 14 October 5 Wortham & Burgate Sunday Club, 7 October, Wortham Village Hall 6 Osiligi Maasai Warriors, 9 October, Lophams’ Village Hall 7 Park Radio, Chris Moyes’s mid-morning coffee break 8 BSEVC Connecting Communities 9 WW1 Beacons of Light, 11 November, Wortham Beacon 10 The Sheila Rush Page 1 1 Wortham Village Hall Quiz Night & Hog Roast ISSUE 1 2 Sue, You Are a Magician Tea’s Made, every Wednesday afternoon 1 3-15 Two Remarkable British Women in WW1 16 Burgate Village News Wortham Walkers 17 Friends of Botesdale Health Centre – Race Night & Supper, 6 October, Rickinghall 18 Beyond the Wall – Out & About, Apple Day, 7 October 19 Bill’s Birds IN THIS 20 Garden Notes by Linda Simpson 21 Heritage Circle 22 W&B Twinning – Singalong evening event with Mike Bowen’s ‘Did You Jive in 55’ 23 Wortham Bowls Club FoWC – Spud & Spout evening, Illustrated Talk 24 Friends of Wortham Church - Spud & Spout –‘ Spanner in the Works’, 19 October. 25 Borderhoppa Group Hires Dates for your Village Hall Diary 26 Rickinghall & District Community Bus WOBUL contact details ADVANCED WARNING! There will be no WOBULs in February and March 2019 as your Editor will be taking a sabbatical. This will be the first time in my seven years producing this newsletter that there will be no issues published. -

Matica Srpska Department of Social Sciences Synaxa Matica Srpska International Journal for Social Sciences, Arts and Culture

MATICA SRPSKA DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL SCIENCES SYNAXA MATICA SRPSKA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR SOCIAL SCIENCES, ARTS AND CULTURE Established in 2017 2–3 (1–2/2018) Editor-in-Chief Časlav Ocić (2017‒ ) Editorial Board Dušan Rnjak Katarina Tomašević Editorial Secretary Jovana Trbojević Language Editor and Proof Reader Aleksandar Pavić Articles are available in full-text at the web site of Matica Srpska http://www.maticasrpska.org.rs/ Copyright © Matica Srpska, Novi Sad, 2018 SYNAXA СИН@КСА♦ΣΎΝΑΞΙΣ♦SYN@XIS Matica Srpska International Journal for Social Sciences, Arts and Culture 2–3 (1–2/2018) NOVI SAD 2018 Publication of this issue was supported by City Department for Culture of Novi Sad and Foundation “Novi Sad 2021” CONTENTS ARTICLES AND TREATISES Srđa Trifković FROM UTOPIA TO DYSTOPIA: THE CREATION OF YUGOSLAVIA IN 1918 1–18 Smiljana Đurović THE GREAT ECONOMIC CRISIS IN INTERWAR YUGOSLAVIA: STATE INTERVENTION 19–35 Svetlana V. Mirčov SERBIAN WRITTEN WORD IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR: STRUGGLING FOR NATIONAL AND STATEHOOD SURVIVAL 37–59 Slavenko Terzić COUNT SAVA VLADISLAVIĆ’S EURO-ASIAN HORIZONS 61–74 Bogoljub Šijaković WISDOM IN CONTEXT: PROVERBS AND PHILOSOPHY 75–85 Milomir Stepić FROM (NEO)CLASSICAL TO POSTMODERN GEOPOLITICAL POSTULATES 87–103 Nino Delić DEMOGRAPHIC TRENDS IN THE DISTRICT OF SMEDEREVO: 1846–1866 105–113 Miša Đurković IDEOLOGICAL AND POLITICAL CONFLICTS ABOUT POPULAR MUSIC IN SERBIA 115–124 Mirjana Veselinović-Hofman TOWARDS A BOTTOMLESS PIT: THE DRAMATURGY OF SILENCE IN THE STRING QUARTET PLAY STRINDBERG BY IVANA STEFANOVIĆ 125–134 Marija Maglov TIME TIIIME TIIIIIIME: CONSIDERING THE PROBLEM OF MUSICAL TIME ON THE EXAMPLE OF VLASTIMIR TRAJKOVIĆ’S POETICS AND THOMAS CLIFTON’S AESTHETICS 135–142 Milan R. -

Flora Sandes a Biography by Adrian Sandes Flora (0217) Was Born in 1876, in Yorkshire

Flora Sandes A biography by Adrian Sandes Flora (0217) was born in 1876, in Yorkshire. She was an exceptionally bright child, and grew up to be a tall, handsome woman, a good rider, an expert shot, and later a capable car driver; she always maintained in fact that she wished she had been born a boy because of her love of adventure. However, she led an uneventful life in London as a secretary until 1913. Then, at the age of 37 she joined the St. John Ambulance Brigade and in 1914 on the outbreak of the first World War she was sent to Serbia with a few other volunteer nurses. Her first 18 months in Serbia were fully occupied with tending to sick and wounded soldiers, though she managed to make two short trips to England to collect funds for her work. On one of them she raised £2000 which she spent on medical necessities. She then transferred to the Serbian Red Cross, for whom she worked as a nurse. With an American nurse she went to a typhus stricken town called Valjevo, where there were no doctors; she duly caught the disease, but recovered. The Serbs were being driven back by their deadly enemies, the Bulgarians, and Flora joined a Serbian ambulance unit at the front until, when the unit could no longer operate as such, she gave up nursing to become a fighting soldier in the 2nd Serbian Infantry Regiment. In this she followed the example of many Serbian women, but it was an extraordinary deed for a nurse of the British St John’s Ambulance. -

![Miranda, 2 | 2010, « Voicing Conflict : Women and 20Th Century Warfare » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Juillet 2010, Consulté Le 16 Février 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2961/miranda-2-2010-%C2%AB-voicing-conflict-women-and-20th-century-warfare-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-01-juillet-2010-consult%C3%A9-le-16-f%C3%A9vrier-2021-2512961.webp)

Miranda, 2 | 2010, « Voicing Conflict : Women and 20Th Century Warfare » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Juillet 2010, Consulté Le 16 Février 2021

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 2 | 2010 Voicing Conflict : Women and 20th Century Warfare Les voix du conflit : femmes et guerres au XXe siècle Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/322 DOI : 10.4000/miranda.322 ISSN : 2108-6559 Éditeur Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Référence électronique Miranda, 2 | 2010, « Voicing Conflict : Women and 20th Century Warfare » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 juillet 2010, consulté le 16 février 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/322 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.322 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 16 février 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. 1 SOMMAIRE Voicing Conflict : Women and 20th Century Warfare Introduction Karen Meschia Front Line Voices Voix sur la ligne de front X-Ray Vision: Women Photograph War Margaret R. Higonnet W.A.A.C.s: Crossing the line in the Great War Claire Bowen Roles in Conflict: The Woman War Reporter Maggie Allison Home Front Voices New Slants on Gender and Power Relations in British Second World War Films Elizabeth de Cacqueray “Careless Talk”: Word Shortage in Elizabeth Bowen’s Wartime Writing Céline Magot « A secret at the heart of darkness opening up » : de Little Eden-A Child at War (1978) à Journey to Nowhere (2008), les mots de la guerre ou les batailles du silence dans l'écriture autobiographique d'Eva Figes Nathalie Vincent-Arnaud Naomi the Poet and Nella the Housewife: Finding a Space to Write from The Wartime Diaries of Naomi Mitchison and Nella Last Karen Meschia Conflict, Power and Gender in Women’s Memories of the Second World War: a Mass- Observation Study Penny Summerfield Voices for Peace Woman as Peacemaker or the Ambivalent Politics of Myth Cyril Selzner Les Filles d’Athéna et des Amazones en Amérique Nicole Ollier Miranda, 2 | 2010 2 When Women Write the First Poem: Louise Driscoll and the “war poem scandal” Jennifer Kilgore-Caradec H.D. -

PDF (All Devices)

Published by: The Irish Times Limited (Irish Times Books) © The Irish Times 2016. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of The Irish Times Limited, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographic rights organisation or as expressly permitted by law. Contents To my daughter Betty, the gift of God ........................................................................... 1 The heroic dead of Ireland – Marshal Foch’s tribute .................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 7 Casualties in Irish regiments on the first day of the Battle of the Somme .................. 10 How The Irish Times reported the Somme .................................................................. 13 An Irishman’s Diary ...................................................................................................... 17 The Irish Times editorial ............................................................................................... 20 Death of daughter of poet Thomas Kettle ................................................................... 22 How the First World War began .................................................................................. 24 Preparing for the ‘Big Push’ ........................................................................................ -

WOMEN's WAR-WORK.—It Would Be Impossible Here to Attempt to Describe the Special

WOMEN'S WAR-WORK.—It would be impossible here to attempt to describe the special war-work done by women of all the belligerent countries in 1914-8; and this article is confined to an outline of women's war-work as organized in the United Kingdom and the United States, beginning with the former. United Kingdom The general dislocation which ensued in industry threw numbers of women workers in the United Kingdom out of employment. At the same time women of independent means, moved by patriotism, came forward in large numbers with offers of voluntary service. It soon became apparent that the well-meant action, of the non-professional women was likely to press heavily on the position of the unemployed wage-earners; and accordingly on Aug. 20 Queen Mary inaugurated the " Queen's Work for Women Fund," technically a branch of the National Relief Fund, to provide employment for as many as possible of the women thrown out of work by the war. The Queen's collecting committee, with Lady Roxburgh as hon. sec., raised the money, but the administration of the fund was in the hands of the Central Committee on Women's Employment, a Government Committee under the chairmanship of the Marchioness of Crewe, with Mary Macarthur (d. 1921) as hon. secretary'. The problem of the Committee was to help to adjust the dislocation of industry, so that unemployed firms and workers in a slack trade might ease the overpressure in other trades. Firms unused to Government work were assisted to undertake War Office contracts, and orders were placed with small establishments employing women, who would otherwise have had to relinquish their businesses. -

TRAILBLAZERS: World War One’S Inspirational Women TRAILBLAZERS: World War One’S Inspirational Women Introduction

TRAILBLAZERS: World War One’s Inspirational Women TRAILBLAZERS: World War One’s Inspirational Women Introduction A trailblazer is someone who goes ahead to find a way through Key categories unexplored territory leaving markers behind which others can follow. They are innovators, the first to do something. During Arts & Culture the First World War many women were trailblazers. Even today their inspirational stories can show us the way. Activism The First World War was a time of political and social change for women. Before the war began, women were already Science protesting for the right to vote in political elections, this is known as the women’s suffrage movement. There were two main forms of women’s suffrage in the UK: the suffragists and Industry the suffragettes. Military In 1897 seperate women’s suffrage societies joined together to form the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies Definitions (NUWSS) which was led by Millicent Fawcett. Suffragists believed that women could prove they should have the right Suffrage: to vote by being responsible citizens. The right to vote in political elections The suffragettes broke away from the suffragist movement and Munition: formed the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) under Military weapons, bullets, Emmeline Pankhurst. They believed it was necessary to use and equipment illegal means to force a change in the law. Prejudice: When the war started, campaigners for women’s rights set Dislike or hostility aside their protests and supported the war effort. Millions without good reason of men left Britain to fight overseas. Women took on more Activism: public responsibilities.