A Fine Brother

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19 to the 21 St Centuries

Centre for British Studies International Conference Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19th to the 21st centuries Belgrade, January 26-27, 2018 Conference: Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19th to the 21st centuries Belgrade, January 26-27, 2018 P R O G R A M M E Venue: Faculty of Political Science of the University of Belgrade, Jove Ilića 165 Friday, January 26, 2018 12.00–12.50 Opening of the Conference: H. E. Denis Keefe, CMG, HM Ambassador to Serbia Prof. Dragan Simić, Dean of the Faculty of Political Science, Belgrade Prof. em. Vukašin Pavlović, President of the Council of the Centre for British Studies, FPS, UoB 13.00–14.30 Panel 1: Serbia, the UK, and Global World Chairperson: Dr. Spyros Economides, London School of Economics and Political Science Panellists: Sir John Randall, former Member of Parliament and Government Deputy Chief Whip British-Serbian Relations H. E. Amb. Branimir Filipović, Assistant Minister, MFA of Serbia British-Serbian Relations since 2000. A View from Serbia David Gowan, CMG, former ambassador of the UK to Serbia and Montenegro British-Serbian Relations since 2000. A View from Britain Prof. Christopher Coker, London School of Economics Britain and the Balkans in Global World 14.30–15.45 Lunch break 1 Conference: Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19th to the 21st centuries Belgrade, January 26-27, 2018 15.45–17.15 Panel 2: Diffi cult Legacies and New Opportunities Chairperson: Prof. Slobodan G. Markovich, Centre for British Studies, FPS, UoB Panellists: Dr. Spyros Economides, London School of Economics Legacy of UN Interventionism in British-Serbian Relations Prof. -

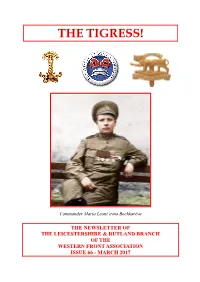

Issue 66 - March 2017 Editorial

THE TIGRESS! Commander Maria Leont’evna Bochkarëva THE NEWSLETTER OF THE LEICESTERSHIRE & RUTLAND BRANCH OF THE WESTERN FRONT ASSOCIATION ISSUE 66 - MARCH 2017 EDITORIAL Welcome again, Ladies and Gentlemen, to the latest edition of “The Tiger”, rechristened “The Tigress” for this special ladies edition! Despite whiling away many a youthful hour under a candlewick bedspread listening to Radio Luxembourg 208, I don’t seem to have much time these days to listen to the radio but I noticed that, on 8th March, Radio 3 dedicated its whole day’s playlist, in recognition of their bold and diverse contribution to music, to female composers one of whom being Elisabeth Lutyens, daughter of architect Edwin. Why did the BBC decide to do this? It was to celebrate International Women’s Day (IWD). I was reminded of the impending IWD last month when researching the remarkable exploits of Russian women in 1917 without whom the revolution may not have occurred exactly as it did 100 years ago. Their story will be recounted later in this Newsletter . The month of March itself could even be described as “Ladies Month” since its very flower, the daffodil, is also known as the birth flower, and its 31 days contain not only IWD (8th) but Lady Day or Annunciation Day (25th) and Mothering Sunday (26th). Militarily, of course, March was named after Mars, the Roman god of war whose month was Martius and from where originated the word martial. Another definition of March is “walk in a military manner with a regular measured tread”, a meaning which countless troops over the centuries learned as part of their basic training. -

The Western Media and the Portrayal of the Rwandan Genocide

History in the Making Volume 3 Article 5 2010 The Western Media and the Portrayal of the Rwandan Genocide Cherice Joyann Estes CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the African History Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Estes, Cherice Joyann (2010) "The Western Media and the Portrayal of the Rwandan Genocide," History in the Making: Vol. 3 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol3/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arthur E. Nelson University Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cherice Joyann Estes The Western Media and the Portrayal of the Rwandan Genocide BY CHERICE JOYANN ESTES ABSTRACT: On December 9, 1948, the United Nations established its Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Genocides, however, have continued to occur, affecting millions of people around the globe. The 1994 genocide in Rwanda resulted in an estimated 800,000 deaths. Global leaders were well aware of the atrocities, but failed to intervene. At the same time, the Western media's reports on Rwanda tended to understate the magnitude of the crisis. This paper explores the Western media's failure to accurately interpret and describe the Rwandan Genocide. Recognizing the outside media’s role in mischaracterizations of the Rwanda situation is particularly useful when attempting to understand why western governments were ineffective in their response to the atrocity. -

Flora Sandes Born: 22

Flora Sandes BORN: 22. 01. 1876 About 80,000 women were employed NATIONALITY: English during World War I as nurses and orderlies at field hospitals. These were usually some distance away from the fighting. Only very PROFESSION: Nurse-turned-soldier few women entered active service in armies. in the Serbian Army Flora Sandes is one such example. DIED: 1955 (date unknown) The daughter of a clergyman, Flora Sandes grew up in the small Yorkshire town of Poppleton. She became a nurse and worked for the St John Ambulance and later worked for the First Aid When World War I began, Sandes was 38. She Nursing Yeomanry (FANY) in Britain. volunteered immediately for an ambulance unit in Serbia that was run by the Red Cross. In 1915, American female nurses carry gas masks with them as they walk through trenches in France. More the Serbian army retreated through the Albanian than 1,500 female nurses from the United States served in the forces during World War. mountains from the armies of Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria. Sandes became separated from her unit and was caught up in battle with a unit of As soon as she could, Sandes returned to Serbia. At the age of 64, Sandes returned to serve in the the Serbian Second Infantry Regiment. Picking She remained in the Serbian Army after the war Serbian forces – this time in World War II. She up a weapon to defend herself, she impressed ended. In June 1919, a special Act of Parliament was captured in uniform by the Germans and the company commander, Colonel Militch and in Serbia was passed to make Sandes the first taken to a military prison hospital. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

British Major-General Charles George Gordon and His Legacies, 1885-1960 Stephanie Laffer

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 Gordon's Ghosts: British Major-General Charles George Gordon and His Legacies, 1885-1960 Stephanie Laffer Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES GORDON‘S GHOSTS: BRITISH MAJOR-GENERAL CHARLES GEORGE GORDON AND HIS LEGACIES, 1885-1960 By STEPHANIE LAFFER A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2010 Copyright © 2010 Stephanie Laffer All Rights Reserve The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Stephanie Laffer defended on February 5, 2010. __________________________________ Charles Upchurch Professor Directing Dissertation __________________________________ Barry Faulk University Representative __________________________________ Max Paul Friedman Committee Member __________________________________ Peter Garretson Committee Member __________________________________ Jonathan Grant Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii For my parents, who always encouraged me… iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation has been a multi-year project, with research in multiple states and countries. It would not have been possible without the generous assistance of the libraries and archives I visited, in both the United States and the United Kingdom. However, without the support of the history department and Florida State University, I would not have been able to complete the project. My advisor, Charles Upchurch encouraged me to broaden my understanding of the British Empire, which led to my decision to study Charles Gordon. Dr. Upchurch‘s constant urging for me to push my writing and theoretical understanding of imperialism further, led to a much stronger dissertation than I could have ever produced on my own. -

Chesterfield Wfa

CHESTERFIELD WFA Newsletter and Magazine issue 36 Patron –Sir Hew Strachan Welcome to Issue 36 - the December2018 FRSE FRHistS Newsletter and Magazine of Chesterfield President - Professor WFA. Peter Simkins MBE FRHistS Vice-Presidents Andre Colliot Professor John Bourne BA PhD FRHistS The Burgomaster of Ypres The Mayor of Albert Lt-Col Graham Parker OBE Professor Gary Sheffield BA MA PhD FRHistS Christopher Pugsley FRHistS Lord Richard Dannat GCB CBE MC DL th For our Meeting on Tuesday 4 December we welcome Roger Lee PhD jssc Dr Phylomena Badsey. Dr Badsey specialises in nursing during the First World War. She also maintains a broad Dr Jack Sheldon Interest in women and warfare, occupation and social www.westernfrontassociation.com change. Branch contacts Dr. Badsey`s presentation will be Tony Bolton (Chairman) "Auxiliary Hospitals and the role of Voluntary Aid anthony.bolton3@btinternet Detachment Nurses during the First World War" .com Mark Macartney The Branch meets at the Labour Club, Unity House, Saltergate, (Deputy Chairman) [email protected] Chesterfield S40 1NF on the first Tuesday of each month. There Jane Lovatt (Treasurer) is plenty of parking available on site and in the adjacent road. Grant Cullen Access to the car park is in Tennyson Road, however, which is (Secretary) [email protected] one way and cannot be accessed directly from Saltergate. Grant Cullen – Branch Secretary Facebook http://www.facebook.com/g roups/157662657604082/ http://www.wfachesterfield.com/ Western Front Association Chesterfield Branch – Meetings 2019 Meetings start at 7.30pm and take place at the Labour Club, Unity House, Saltergate, Chesterfield S40 1NF January 8th Jan.8th Note Date Change. -

Under Crescent and Star

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES ^^H m ' '- PI; H ; I UNDER CRESCENT AND STAR BY LIEUT. -COL. ANDKEW HAGGAKD, D.S.O. ' AUTHOR OF 'DODO AND I," TEMPEST -TORN,' ETC. WITH PORTRAIT WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS EDINBURGH AND LONDON MDCCCXCV DT 107.3 TO ALL MY OLD COMRADES WHO FOUGHT OR DIED IN EGYPT. ANDREW HAGGARD. NAVAL AND MILITARY CLUB, November 1895. CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. PAGE " Learning Arabic The 1st Reserve Depot Devils in hell "- " " " Too late for the battle We don't want to work The dear old false prophet" The mosquitos' revenge on the musketeers . 1 CHAPTER II. Cairo The domestic ass Security in the city The Khedive on Tommy Atkins Bedaween on the road Parapets and pyramids Alexandria . .14 CHAPTER III. Old Egyptian army worthless How disposed of under Hicks Pasha and Valentine Baker Baker's disappointment Sir Evelyn Wood to command Constitution of the new Egyp- tian army Officers' contracts Coetlogou The Duke of Sutherland Medals and promotions Sugar-candy . 23 CHAPTER IV. Formation of the new army How officered Difficulties of lan- guage and drill The music question We conform to Ma- homedan customs Big dinners The Khedive's reception Lord Dufferin's pleasant ways . .39 Vlll CONTENTS. CHAPTER V. The Duke of Hamilton and Turner His kindness to the Shrop- shire Regiment The Khedive at Alexandria The officers visit him on accession day Ramadan begins Drilling at night We make cholera camps and cholera hospital Win- gate's good work Turner's pluck and peculiarities The epidemic awful in Cairo Death lists at dinner Devotion of . -

AYESHA CONTEH, 8S the First World War

A VIRTUAL MUSEUM BY AYESHA CONTEH, 8S The First World war. All the facts and stories of the harrowing, long four year war. About the war - myths and truth. Yes, Women did not fight in the armed The First World War broke out in August forces of most nations in WW1, but 1914, killing over 9 million people and there were lots of women in a range of injuring over 21 million during 21 battles across the world. Fighting finally ceased roles including auxiliary roles in the on 11th November 1918 and the date has army as well as traditional nursing roles. since been commemorated as Some women were killed, some saw the Remembrance Day, in recognition of the trenches first-hand, and all of their scale of human lives lost in the conflict. roles were crucial to the war effort. A popular thought about the war is that women hardly contributed and that the war was fought and experienced by men, But The truth is surprisingly far from that. FLORA SANDES Officer of Royal Serbian Army, WW1. Born on January 22 1876, Flora Sandes was a British woman who served as an officer of the Royal Serbian Army and was the only British woman officially to serve as a soldier in WWI. She started off as a St. John Ambulance volunteer, and then travelled to the Kingdom of Serbia, where she was welcomed and went on to enroll in the Serbian army. Flora recalled how she "naturally drifted, in successive stages, from a nurse into a soldier. The soldiers seem to have taken it for granted that anyone who could ride and shoot, and I could do both, would be a soldier, in such a crisis." Where was WW1 fought? Did you know? When people remember the First World War in Britain today, That four million non white people from they usually pay respects by visiting local war memorials or different parts of the world were recruited visiting the graves of family members who were involved. -

WOBUL October 2018

Your local journal with news, past and future events and interesting articles 2 2 Palgrave Cinema – All The Money In The World, Saturday 13 October 3 Emma’s Jumble Sale, 27 October, Wortham Village Hall 4 Charity Fundraiser by Mike Bowen – Did You Jive in 55 – Sunday 14 October 5 Wortham & Burgate Sunday Club, 7 October, Wortham Village Hall 6 Osiligi Maasai Warriors, 9 October, Lophams’ Village Hall 7 Park Radio, Chris Moyes’s mid-morning coffee break 8 BSEVC Connecting Communities 9 WW1 Beacons of Light, 11 November, Wortham Beacon 10 The Sheila Rush Page 1 1 Wortham Village Hall Quiz Night & Hog Roast ISSUE 1 2 Sue, You Are a Magician Tea’s Made, every Wednesday afternoon 1 3-15 Two Remarkable British Women in WW1 16 Burgate Village News Wortham Walkers 17 Friends of Botesdale Health Centre – Race Night & Supper, 6 October, Rickinghall 18 Beyond the Wall – Out & About, Apple Day, 7 October 19 Bill’s Birds IN THIS 20 Garden Notes by Linda Simpson 21 Heritage Circle 22 W&B Twinning – Singalong evening event with Mike Bowen’s ‘Did You Jive in 55’ 23 Wortham Bowls Club FoWC – Spud & Spout evening, Illustrated Talk 24 Friends of Wortham Church - Spud & Spout –‘ Spanner in the Works’, 19 October. 25 Borderhoppa Group Hires Dates for your Village Hall Diary 26 Rickinghall & District Community Bus WOBUL contact details ADVANCED WARNING! There will be no WOBULs in February and March 2019 as your Editor will be taking a sabbatical. This will be the first time in my seven years producing this newsletter that there will be no issues published. -

Women and Wwi Some Images

WOMEN AND WWI SOME IMAGES Women and the Military during World War One By Professor Joanna Bourke (Last updated 2011-03-03) Women combatants By 12 August 1914, Englishwoman Flora Sandes knew that if she wanted an exciting life, she would have to fight for it. That was the date she steamed out of London, along with 36 other eager nurses, bound for Serbia. Within 18 months, during the great retreat to Albania, she had exchanged bandages for guns. She insisted on acting as a soldier, and being treated as such; therefore, like male combatants, she cared for the wounded, but only 'between shots'. She curtly informed one correspondent on 10 November 1916 that if people thought she ought to be a nurse instead of a soldier, they should be told that 'we have Red Cross men for first aid'. Her martial valour during World War One was recognised in June 1919 when a special Serbian Act of Parliament made her the first woman to be commissioned in the Serbian Army. This jolly, buxom daughter of a retired vicar living in the peaceful village of Thornton Heath in the Suffolk countryside was an unlikely candidate for the warrior role. Although she had been given elementary medical and military training in the Women's First Aid Yeomanry Corps and St John's Ambulance, she had no regrets about leaving nursing for the life of a combatant. Indeed, she relished those times when the savage explosion of her bombs was followed by a 'few groans and then silence' since a 'tremendous hullabaloo' signalled that she had inflicted 'only a few scratches, or the top of someone's finger.. -

Lincoln Attained. He Is Master of Th^Y-^Itical Help the Project Than Tho

* c NEW YUKK HERALD, WEDKESDj!Y, JULY 9, 1873.-TKIPLE SHKKT. Hg % sen intental Ingei In Onr Politic*. is a soldier j he knowj the felicity of me. The result is that yesterday we signed heiid of a tributary of the Zambezi, and if of A. T. Stewart 4 Co., has been made the re- 1 a or a handsome testimonial from his "r'm -rtnn'-v- Mnn.4 .« lU.t l.k. clplent or » IIEKALD CI»Ter (tueitloni thkn Ruffrkgt His ideas of the have an on certain conditions, Bu w|w«« vi tiuo mnvuuv v* »ui»» « »» I NEW YORK authority. Presidency agreement by which, friends. Protection.The Apathr end Silence of been that it is in senses a they agree to form a company, of which I am ab<jve the sea is not a mistake this time HS; AND ANY STREET. always many great Jo in L. Tnc';er, one of the good old BROADWAY office. to be to suit and to inion must be correct Bat oar the Republican Party. True and faithful as he has been,personal President, my views, give opi of the Tremont House, Boston, and recentlyUaAlordst me and friends a the of the new Clifford at Mass., was We are not insensible to the valne of many there are many thingB he has done that Bhow my majority of stock." sp< report from Khartoam, byoorremdent's House, Plymouth. | yJAMES GORDON BENNETT, a to to the belief that, in Thns we see how political was mixed the of Sir Samuel Baker, is drowned while bathing at Plymouth, on the 6th of the issues which our political friends are tendency Cre-tarism, jobbery emphaticau>rityinstant.