WOMEN's WAR-WORK.—It Would Be Impossible Here to Attempt to Describe the Special

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glasgow Women's Library

SCOTTISH ARCHIVES 2016 Volume 22 © The Scottish Records Association Around the Archives Glasgow Women’s Library Nicola Maksymuik In the 25 years since its inception, Glasgow Women’s Library (GWL) has faced many challenges, including four changes of location, growing from a completely unfunded organisation run solely by volunteers to what it has become today – a well-respected, award-winning institution with unique archive, library and museum collections dedicated to women’s history. GWL is the only Accredited Museum of women’s history in the UK and in 2015 was awarded ‘Recognised Collection of National Significance’ status by Museums Galleries Scotland. As well as the archive and artefact collections that have grown over its 25- year history, the library also runs an innovative seasonal programme of public events and learning opportunities. Among its Core Projects there is also an Adult Literacy and Numeracy project; a Black and Minority Ethnic Women’s project; and a National Lifelong Learning project that delivers events and resources across Scotland. All of the library’s projects and programmes utilise the archive and museum collections in their work, and the collections inform and underpin almost everything that the library does. The library developed from an arts organisation called Women In Profile (WIP), which was established in 1987 with the aim of ensuring that women were represented when Glasgow became the European City of Culture in 1990. WIP consisted of artists, activists, academics and students, including the library’s co-founder and current Creative Development Manager, Dr Adele Patrick. The group ran projects, events, workshops and exhibitions before and during 1990. -

Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19 to the 21 St Centuries

Centre for British Studies International Conference Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19th to the 21st centuries Belgrade, January 26-27, 2018 Conference: Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19th to the 21st centuries Belgrade, January 26-27, 2018 P R O G R A M M E Venue: Faculty of Political Science of the University of Belgrade, Jove Ilića 165 Friday, January 26, 2018 12.00–12.50 Opening of the Conference: H. E. Denis Keefe, CMG, HM Ambassador to Serbia Prof. Dragan Simić, Dean of the Faculty of Political Science, Belgrade Prof. em. Vukašin Pavlović, President of the Council of the Centre for British Studies, FPS, UoB 13.00–14.30 Panel 1: Serbia, the UK, and Global World Chairperson: Dr. Spyros Economides, London School of Economics and Political Science Panellists: Sir John Randall, former Member of Parliament and Government Deputy Chief Whip British-Serbian Relations H. E. Amb. Branimir Filipović, Assistant Minister, MFA of Serbia British-Serbian Relations since 2000. A View from Serbia David Gowan, CMG, former ambassador of the UK to Serbia and Montenegro British-Serbian Relations since 2000. A View from Britain Prof. Christopher Coker, London School of Economics Britain and the Balkans in Global World 14.30–15.45 Lunch break 1 Conference: Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19th to the 21st centuries Belgrade, January 26-27, 2018 15.45–17.15 Panel 2: Diffi cult Legacies and New Opportunities Chairperson: Prof. Slobodan G. Markovich, Centre for British Studies, FPS, UoB Panellists: Dr. Spyros Economides, London School of Economics Legacy of UN Interventionism in British-Serbian Relations Prof. -

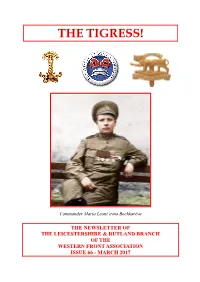

Issue 66 - March 2017 Editorial

THE TIGRESS! Commander Maria Leont’evna Bochkarëva THE NEWSLETTER OF THE LEICESTERSHIRE & RUTLAND BRANCH OF THE WESTERN FRONT ASSOCIATION ISSUE 66 - MARCH 2017 EDITORIAL Welcome again, Ladies and Gentlemen, to the latest edition of “The Tiger”, rechristened “The Tigress” for this special ladies edition! Despite whiling away many a youthful hour under a candlewick bedspread listening to Radio Luxembourg 208, I don’t seem to have much time these days to listen to the radio but I noticed that, on 8th March, Radio 3 dedicated its whole day’s playlist, in recognition of their bold and diverse contribution to music, to female composers one of whom being Elisabeth Lutyens, daughter of architect Edwin. Why did the BBC decide to do this? It was to celebrate International Women’s Day (IWD). I was reminded of the impending IWD last month when researching the remarkable exploits of Russian women in 1917 without whom the revolution may not have occurred exactly as it did 100 years ago. Their story will be recounted later in this Newsletter . The month of March itself could even be described as “Ladies Month” since its very flower, the daffodil, is also known as the birth flower, and its 31 days contain not only IWD (8th) but Lady Day or Annunciation Day (25th) and Mothering Sunday (26th). Militarily, of course, March was named after Mars, the Roman god of war whose month was Martius and from where originated the word martial. Another definition of March is “walk in a military manner with a regular measured tread”, a meaning which countless troops over the centuries learned as part of their basic training. -

Process Paper and Bibliography

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources Books Kenney, Annie. Memories of a Militant. London: Edward Arnold & Co, 1924. Autobiography of Annie Kenney. Lytton, Constance, and Jane Warton. Prisons & Prisoners. London: William Heinemann, 1914. Personal experiences of Lady Constance Lytton. Pankhurst, Christabel. Unshackled. London: Hutchinson and Co (Publishers) Ltd, 1959. Autobiography of Christabel Pankhurst. Pankhurst, Emmeline. My Own Story. London: Hearst’s International Library Co, 1914. Autobiography of Emmeline Pankhurst. Newspaper Articles "Amazing Scenes in London." Western Daily Mercury (Plymouth), March 5, 1912. Window breaking in March 1912, leading to trials of Mrs. Pankhurst and Mr. & Mrs. Pethick- Lawrence. "The Argument of the Broken Pane." Votes for Women (London), February 23, 1912. The argument of the stone: speech delivered by Mrs Pankhurst on Feb 16, 1912 honoring released prisoners who had served two or three months for window-breaking demonstration in November 1911. "Attempt to Burn Theatre Royal." The Scotsman (Edinburgh), July 19, 1912. PM Asquith's visit hailed by Irish Nationalists, protested by Suffragettes; hatchet thrown into Mr. Asquith's carriage, attempt to burn Theatre Royal. "By the Vanload." Lancashire Daily Post (Preston), February 15, 1907. "Twenty shillings or fourteen days." The women's raid on Parliament on Feb 13, 1907: Christabel Pankhurst gets fourteen days and Sylvia Pankhurst gets 3 weeks in prison. "Coal That Cooks." The Suffragette (London), July 18, 1913. Thirst strikes. Attempts to escape from "Cat and Mouse" encounters. "Churchill Gives Explanation." Dundee Courier (Dundee), July 15, 1910. Winston Churchill's position on the Conciliation Bill. "The Ejection." Morning Post (London), October 24, 1906. 1 The day after the October 23rd Parliament session during which Premier Henry Campbell- Bannerman cold-shouldered WSPU, leading to protest led by Mrs Pankhurst that led to eleven arrests, including that of Mrs Pethick-Lawrence and gave impetus to the movement. -

Flora Sandes Born: 22

Flora Sandes BORN: 22. 01. 1876 About 80,000 women were employed NATIONALITY: English during World War I as nurses and orderlies at field hospitals. These were usually some distance away from the fighting. Only very PROFESSION: Nurse-turned-soldier few women entered active service in armies. in the Serbian Army Flora Sandes is one such example. DIED: 1955 (date unknown) The daughter of a clergyman, Flora Sandes grew up in the small Yorkshire town of Poppleton. She became a nurse and worked for the St John Ambulance and later worked for the First Aid When World War I began, Sandes was 38. She Nursing Yeomanry (FANY) in Britain. volunteered immediately for an ambulance unit in Serbia that was run by the Red Cross. In 1915, American female nurses carry gas masks with them as they walk through trenches in France. More the Serbian army retreated through the Albanian than 1,500 female nurses from the United States served in the forces during World War. mountains from the armies of Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria. Sandes became separated from her unit and was caught up in battle with a unit of As soon as she could, Sandes returned to Serbia. At the age of 64, Sandes returned to serve in the the Serbian Second Infantry Regiment. Picking She remained in the Serbian Army after the war Serbian forces – this time in World War II. She up a weapon to defend herself, she impressed ended. In June 1919, a special Act of Parliament was captured in uniform by the Germans and the company commander, Colonel Militch and in Serbia was passed to make Sandes the first taken to a military prison hospital. -

Chesterfield Wfa

CHESTERFIELD WFA Newsletter and Magazine issue 36 Patron –Sir Hew Strachan Welcome to Issue 36 - the December2018 FRSE FRHistS Newsletter and Magazine of Chesterfield President - Professor WFA. Peter Simkins MBE FRHistS Vice-Presidents Andre Colliot Professor John Bourne BA PhD FRHistS The Burgomaster of Ypres The Mayor of Albert Lt-Col Graham Parker OBE Professor Gary Sheffield BA MA PhD FRHistS Christopher Pugsley FRHistS Lord Richard Dannat GCB CBE MC DL th For our Meeting on Tuesday 4 December we welcome Roger Lee PhD jssc Dr Phylomena Badsey. Dr Badsey specialises in nursing during the First World War. She also maintains a broad Dr Jack Sheldon Interest in women and warfare, occupation and social www.westernfrontassociation.com change. Branch contacts Dr. Badsey`s presentation will be Tony Bolton (Chairman) "Auxiliary Hospitals and the role of Voluntary Aid anthony.bolton3@btinternet Detachment Nurses during the First World War" .com Mark Macartney The Branch meets at the Labour Club, Unity House, Saltergate, (Deputy Chairman) [email protected] Chesterfield S40 1NF on the first Tuesday of each month. There Jane Lovatt (Treasurer) is plenty of parking available on site and in the adjacent road. Grant Cullen Access to the car park is in Tennyson Road, however, which is (Secretary) [email protected] one way and cannot be accessed directly from Saltergate. Grant Cullen – Branch Secretary Facebook http://www.facebook.com/g roups/157662657604082/ http://www.wfachesterfield.com/ Western Front Association Chesterfield Branch – Meetings 2019 Meetings start at 7.30pm and take place at the Labour Club, Unity House, Saltergate, Chesterfield S40 1NF January 8th Jan.8th Note Date Change. -

AYESHA CONTEH, 8S the First World War

A VIRTUAL MUSEUM BY AYESHA CONTEH, 8S The First World war. All the facts and stories of the harrowing, long four year war. About the war - myths and truth. Yes, Women did not fight in the armed The First World War broke out in August forces of most nations in WW1, but 1914, killing over 9 million people and there were lots of women in a range of injuring over 21 million during 21 battles across the world. Fighting finally ceased roles including auxiliary roles in the on 11th November 1918 and the date has army as well as traditional nursing roles. since been commemorated as Some women were killed, some saw the Remembrance Day, in recognition of the trenches first-hand, and all of their scale of human lives lost in the conflict. roles were crucial to the war effort. A popular thought about the war is that women hardly contributed and that the war was fought and experienced by men, But The truth is surprisingly far from that. FLORA SANDES Officer of Royal Serbian Army, WW1. Born on January 22 1876, Flora Sandes was a British woman who served as an officer of the Royal Serbian Army and was the only British woman officially to serve as a soldier in WWI. She started off as a St. John Ambulance volunteer, and then travelled to the Kingdom of Serbia, where she was welcomed and went on to enroll in the Serbian army. Flora recalled how she "naturally drifted, in successive stages, from a nurse into a soldier. The soldiers seem to have taken it for granted that anyone who could ride and shoot, and I could do both, would be a soldier, in such a crisis." Where was WW1 fought? Did you know? When people remember the First World War in Britain today, That four million non white people from they usually pay respects by visiting local war memorials or different parts of the world were recruited visiting the graves of family members who were involved. -

WOBUL October 2018

Your local journal with news, past and future events and interesting articles 2 2 Palgrave Cinema – All The Money In The World, Saturday 13 October 3 Emma’s Jumble Sale, 27 October, Wortham Village Hall 4 Charity Fundraiser by Mike Bowen – Did You Jive in 55 – Sunday 14 October 5 Wortham & Burgate Sunday Club, 7 October, Wortham Village Hall 6 Osiligi Maasai Warriors, 9 October, Lophams’ Village Hall 7 Park Radio, Chris Moyes’s mid-morning coffee break 8 BSEVC Connecting Communities 9 WW1 Beacons of Light, 11 November, Wortham Beacon 10 The Sheila Rush Page 1 1 Wortham Village Hall Quiz Night & Hog Roast ISSUE 1 2 Sue, You Are a Magician Tea’s Made, every Wednesday afternoon 1 3-15 Two Remarkable British Women in WW1 16 Burgate Village News Wortham Walkers 17 Friends of Botesdale Health Centre – Race Night & Supper, 6 October, Rickinghall 18 Beyond the Wall – Out & About, Apple Day, 7 October 19 Bill’s Birds IN THIS 20 Garden Notes by Linda Simpson 21 Heritage Circle 22 W&B Twinning – Singalong evening event with Mike Bowen’s ‘Did You Jive in 55’ 23 Wortham Bowls Club FoWC – Spud & Spout evening, Illustrated Talk 24 Friends of Wortham Church - Spud & Spout –‘ Spanner in the Works’, 19 October. 25 Borderhoppa Group Hires Dates for your Village Hall Diary 26 Rickinghall & District Community Bus WOBUL contact details ADVANCED WARNING! There will be no WOBULs in February and March 2019 as your Editor will be taking a sabbatical. This will be the first time in my seven years producing this newsletter that there will be no issues published. -

Be Anvil Or Hammer!

Be anvil or hammer! You must sink or swim Be the master and win Or serve and lose Suffer or triumph Be anvil or hammer – Goethe INTRODUCTION In 1910 the women chainmakers of Cradley Heath focussed the world’s attention on the plight of Britain’s low- paid women workers. In their back yard forges hundreds of women laid down their tools to strike for a living wage. Led by the charismatic union organiser and campaigner, Mary Macarthur, the women’s struggle became a national and international cause célèbre . After ten long weeks, they won the dispute and increased their earnings from as little as 5 shillings (25p) to 11 shillings (55p) a week. Their victory helped to make the principle of a national minimum wage a reality. Mary Macarthur proposed that surplus money in the strike fund should be used to build a ‘centre of social and industrial activity in the district’. Thousands of local people turned out for the opening of The Cradley Heath Workers’ Institute on 10 June 1912. In 2004, the Workers’ Institute was threatened when plans for a bypass were announced. In 2006, thanks to a Heritage Lottery Fund grant of £1.535 million, the Institute was moved brick by brick to the Black Country Living Museum where it now stands as the last physical reminder of the women’s 1910 strike. 3 CHAINMAKING IN CRADLEY HEATH The foggers collected the finished chain and took a During the 19 th century, the Black Country, and percentage of the money the manufacturers paid, especially the area centred on Cradley Heath, usually 25 per cent. -

Women and Wwi Some Images

WOMEN AND WWI SOME IMAGES Women and the Military during World War One By Professor Joanna Bourke (Last updated 2011-03-03) Women combatants By 12 August 1914, Englishwoman Flora Sandes knew that if she wanted an exciting life, she would have to fight for it. That was the date she steamed out of London, along with 36 other eager nurses, bound for Serbia. Within 18 months, during the great retreat to Albania, she had exchanged bandages for guns. She insisted on acting as a soldier, and being treated as such; therefore, like male combatants, she cared for the wounded, but only 'between shots'. She curtly informed one correspondent on 10 November 1916 that if people thought she ought to be a nurse instead of a soldier, they should be told that 'we have Red Cross men for first aid'. Her martial valour during World War One was recognised in June 1919 when a special Serbian Act of Parliament made her the first woman to be commissioned in the Serbian Army. This jolly, buxom daughter of a retired vicar living in the peaceful village of Thornton Heath in the Suffolk countryside was an unlikely candidate for the warrior role. Although she had been given elementary medical and military training in the Women's First Aid Yeomanry Corps and St John's Ambulance, she had no regrets about leaving nursing for the life of a combatant. Indeed, she relished those times when the savage explosion of her bombs was followed by a 'few groans and then silence' since a 'tremendous hullabaloo' signalled that she had inflicted 'only a few scratches, or the top of someone's finger.. -

Woman and Her Sphere Catalogue 193

Woman and her Sphere Catalogue 193 Item # 136 Elizabeth Crawford 5 Owen’s Row London EC1V 4NP 0207-278-9479 [email protected] Index to Catalogue Suffrage Non-fiction: Items 1-15 Suffrage Biography: Items 16-22 Suffrage Fiction: Items 23-32 Suffrage Ephemera: Items 33-136 Suffrage Postcards: Real Photographic: Items 137-160 Suffrage Postcards: Suffrage Artist: Items 161-173 Suffrage Postcards: Commercial Comic: Items 174-200 General Non-fiction: Items 201-327 General Biography: Items 328-451 General Ephemera: Items 452-516 General Postcards: Items 517-521 General Fiction: Items 522-532 Women and the First World War: Items 533-546 Suffrage Non-fiction 1. BILLINGTON-GREIG, Teresa The Militant Suffrage Movement: emancipation in a hurry Frank Palmer no date [1911] [14205] 'I write this book in criticism of the militant suffrage movement beccause I am impelled to do so by forces as strong as those which kept me five years within its ranks....I am a feminist, a rebel, and a suffragist...' She had been an early member of the WSPU and then a founding member of the Women's Freedom League and tells the history of the movement from her viewpoint. An important and very scarce book. Good - ex-library £120 2. BLACKBURN, Helen Record of Women's Suffrage; a record of the women's suffrage movement in the British Isles with biographical sketches of Miss Becker Williams & Norgate 1902 [14313] Extremely useful - in fact, indispensable as a history of the 19th-century suffrage movement. Includes the names of many supporters and a chronological bibliography. -

Alan Cumming Glasgow [email protected] 94(100)"1914/1918" 355.415.6(497.11)"1918"

Alan Cumming Glasgow [email protected] https://doi.org/10.18485/ai_godine_ww1.2019.ch5 94(100)"1914/1918" 355.415.6(497.11)"1918" HUMANITY AND EMPOWERMENT: THE ROLE OF THE SCOTTISH WOMEN’S HOSPITAL UNITS IN SERBIA BETWEEN 1914-1919 Introduction: So, the vote has come! Fancy it’s having taken the war to show them how ready we were to work! Or even to show that that work was necessary. Where do they think the world would have been without women’s work all these ages?1 These words were not being remonstrated before a chamber of men, in the United Kingdom’s Houses of Parliament during the Electoral Reform bill in May 1917. They were written by Dr Elsie Inglis, an innovative Scottish doctor, pioneer in women’s medicine, leading light in Scotland’s suffrage movement and founder of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals. This letter to her sister, is not being transcribed in a comfortable middle class house in the suburbs of Edinburgh, but from Reni, a small town on the banks of the river Danube in South Ukraine. It’s June 1917 and Dr Inglis is writing from a small tent which is part of a field hospital belonging to the Scottish Women’s Hospitals (SWH). They were supporting the Russians and Romanians, but mainly two Serbian divisions. The fighting 1 Francis Balfour, Dr Elsie Inglis (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1918), p. 82. 118 Alan Cumming was intense and war in the Dobrudja region showed no mercy to troops nor civilians alike. Offensives and retreats meant huge casualties from bullets and the twisted metal shards from shrapnel as the bombs rained day and night.