Women Warriors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil War Guide1

Produced by Cincinnati Museum Center at Union Terminal Contents Teacher Guide 3 Activity 1: Billy Yank and Johnny Reb 6 Activity 2: A War Map 8 Activity 3: Young People in the Civil War 9 Timeline of the Civil War 10 Activity 4: African Americans in the Civil War 12 Activity 5: Writing a Letter Home 14 Activity 6: Political Cartoons 15 Credits Content: Barbara Glass, Glass Clarity, Inc. Newspaper Activities: Kathy Liber, Newspapers In Education Manager, The Cincinnati Enquirer Cover and Template Design:Gail Burt For More Information Border Illustration Graphic: Sarah Stoutamire Layout Design: Karl Pavloff,Advertising Art Department, The Cincinnati Enquirer www.libertyontheborder.org Illustrations: Katie Timko www.cincymuseum.org Photos courtesy of Cincinnati Museum Center Photograph and Print Collection Cincinnati.Com/nie 2 Teacher Guide This educational booklet contains activities to help prepare students in grades 4-8 for a visit to Liberty on the Border, a his- tory exhibit developed by Cincinnati Museum Center at Union Terminal.The exhibit tells the story of the American Civil War through photographs, prints, maps, sheet music, three-dimensional objects, and other period materials. If few southern soldiers were wealthy Activity 2: A War Map your class cannot visit the exhibit, the slave owners, but most were from activity sheets provided here can be used rural agricultural areas. Farming was Objectives in conjunction with your textbook or widespread in the North, too, but Students will: another educational experience related because the North was more industri- • Examine a map of Civil War America to the Civil War. Included in each brief alized than the South, many northern • Use information from a chart lesson plan below, you will find objectives, soldiers had worked in factories and • Identify the Mississippi River, the suggested class procedures, and national mills. -

Eastmont High School Items

TO: Board of Directors FROM: Garn Christensen, Superintendent SUBJECT: Requests for Surplus DATE: June 7, 2021 CATEGORY ☐Informational ☐Discussion Only ☐Discussion & Action ☒Action BACKGROUND INFORMATION AND ADMINISTRATIVE CONSIDERATION Staff from the following buildings have curriculum, furniture, or equipment lists and the Executive Directors have reviewed and approved this as surplus: 1. Cascade Elementary items. 2. Grant Elementary items. 3. Kenroy Elementary items. 4. Lee Elementary items. 5. Rock Island Elementary items. 6. Clovis Point Intermediate School items. 7. Sterling Intermediate School items. 8. Eastmont Junior High School items. 9. Eastmont High School items. 10. Eastmont District Office items. Grant Elementary School Library, Kenroy Elementary School Library, and Lee Elementary School Library staff request the attached lists of library books be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. Sterling Intermediate School Library staff request the attached list of old social studies textbooks be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. Eastmont Junior High School Library staff request the attached lists of library books and textbooks for both EJHS and Clovis Point Intermediate School be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. Eastmont High School Library staff request the attached lists of library books for both EHS and elementary schools be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. ATTACHMENTS FISCAL IMPACT ☒None ☒Revenue, if sold RECOMMENDATION The administration recommends the Board authorize said property as surplus. Eastmont Junior High School Eastmont School District #206 905 8th St. NE • East Wenatchee, WA 98802 • Telephone (509)884-6665 Amy Dorey, Principal Bob Celebrezze, Assistant Principal Holly Cornehl, Asst. -

Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19 to the 21 St Centuries

Centre for British Studies International Conference Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19th to the 21st centuries Belgrade, January 26-27, 2018 Conference: Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19th to the 21st centuries Belgrade, January 26-27, 2018 P R O G R A M M E Venue: Faculty of Political Science of the University of Belgrade, Jove Ilića 165 Friday, January 26, 2018 12.00–12.50 Opening of the Conference: H. E. Denis Keefe, CMG, HM Ambassador to Serbia Prof. Dragan Simić, Dean of the Faculty of Political Science, Belgrade Prof. em. Vukašin Pavlović, President of the Council of the Centre for British Studies, FPS, UoB 13.00–14.30 Panel 1: Serbia, the UK, and Global World Chairperson: Dr. Spyros Economides, London School of Economics and Political Science Panellists: Sir John Randall, former Member of Parliament and Government Deputy Chief Whip British-Serbian Relations H. E. Amb. Branimir Filipović, Assistant Minister, MFA of Serbia British-Serbian Relations since 2000. A View from Serbia David Gowan, CMG, former ambassador of the UK to Serbia and Montenegro British-Serbian Relations since 2000. A View from Britain Prof. Christopher Coker, London School of Economics Britain and the Balkans in Global World 14.30–15.45 Lunch break 1 Conference: Serbian (Yugoslav) – British Relations from the 19th to the 21st centuries Belgrade, January 26-27, 2018 15.45–17.15 Panel 2: Diffi cult Legacies and New Opportunities Chairperson: Prof. Slobodan G. Markovich, Centre for British Studies, FPS, UoB Panellists: Dr. Spyros Economides, London School of Economics Legacy of UN Interventionism in British-Serbian Relations Prof. -

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930S

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Ariel Mae Lambe All rights reserved ABSTRACT Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe This dissertation shows that during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) diverse Cubans organized to support the Spanish Second Republic, overcoming differences to coalesce around a movement they defined as antifascism. Hundreds of Cuban volunteers—more than from any other Latin American country—traveled to Spain to fight for the Republic in both the International Brigades and the regular Republican forces, to provide medical care, and to serve in other support roles; children, women, and men back home worked together to raise substantial monetary and material aid for Spanish children during the war; and longstanding groups on the island including black associations, Freemasons, anarchists, and the Communist Party leveraged organizational and publishing resources to raise awareness, garner support, fund, and otherwise assist the cause. The dissertation studies Cuban antifascist individuals, campaigns, organizations, and networks operating transnationally to help the Spanish Republic, contextualizing these efforts in Cuba’s internal struggles of the 1930s. It argues that both transnational solidarity and domestic concerns defined Cuban antifascism. First, Cubans confronting crises of democracy at home and in Spain believed fascism threatened them directly. Citing examples in Ethiopia, China, Europe, and Latin America, Cuban antifascists—like many others—feared a worldwide menace posed by fascism’s spread. -

According to Wikipedia 2011 with Some Addictions

American MilitMilitaryary Historians AAA-A---FFFF According to Wikipedia 2011 with some addictions Society for Military History From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Society for Military History is an United States -based international organization of scholars who research, write and teach military history of all time periods and places. It includes Naval history , air power history and studies of technology, ideas, and homefronts. It publishes the quarterly refereed journal titled The Journal of Military History . An annual meeting is held every year. Recent meetings have been held in Frederick, Maryland, from April 19-22, 2007; Ogden, Utah, from April 17- 19, 2008; Murfreesboro, Tennessee 2-5 April 2009 and Lexington, Virginia 20-23 May 2010. The society was established in 1933 as the American Military History Foundation, renamed in 1939 the American Military Institute, and renamed again in 1990 as the Society for Military History. It has over 2,300 members including many prominent scholars, soldiers, and citizens interested in military history. [citation needed ] Membership is open to anyone and includes a subscription to the journal. Officers Officers (2009-2010) are: • President Dr. Brian M. Linn • Vice President Dr. Joseph T. Glatthaar • Executive Director Dr. Robert H. Berlin • Treasurer Dr. Graham A. Cosmas • Journal Editor Dr. Bruce Vandervort • Journal Managing Editors James R. Arnold and Roberta Wiener • Recording Secretary & Photographer Thomas Morgan • Webmaster & Newsletter Editor Dr. Kurt Hackemer • Archivist Paul A. -

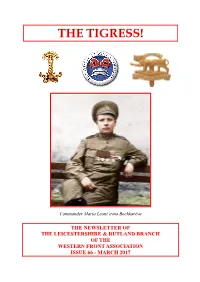

Issue 66 - March 2017 Editorial

THE TIGRESS! Commander Maria Leont’evna Bochkarëva THE NEWSLETTER OF THE LEICESTERSHIRE & RUTLAND BRANCH OF THE WESTERN FRONT ASSOCIATION ISSUE 66 - MARCH 2017 EDITORIAL Welcome again, Ladies and Gentlemen, to the latest edition of “The Tiger”, rechristened “The Tigress” for this special ladies edition! Despite whiling away many a youthful hour under a candlewick bedspread listening to Radio Luxembourg 208, I don’t seem to have much time these days to listen to the radio but I noticed that, on 8th March, Radio 3 dedicated its whole day’s playlist, in recognition of their bold and diverse contribution to music, to female composers one of whom being Elisabeth Lutyens, daughter of architect Edwin. Why did the BBC decide to do this? It was to celebrate International Women’s Day (IWD). I was reminded of the impending IWD last month when researching the remarkable exploits of Russian women in 1917 without whom the revolution may not have occurred exactly as it did 100 years ago. Their story will be recounted later in this Newsletter . The month of March itself could even be described as “Ladies Month” since its very flower, the daffodil, is also known as the birth flower, and its 31 days contain not only IWD (8th) but Lady Day or Annunciation Day (25th) and Mothering Sunday (26th). Militarily, of course, March was named after Mars, the Roman god of war whose month was Martius and from where originated the word martial. Another definition of March is “walk in a military manner with a regular measured tread”, a meaning which countless troops over the centuries learned as part of their basic training. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War

History in the Making Volume 9 Article 5 January 2016 Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War Heather K. Garrett CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Garrett, Heather K. (2016) "Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War," History in the Making: Vol. 9 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol9/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Articles Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War By Heather K. Garrett Abstract: When asked of their memory of the American Revolution, most would reference George Washington or Paul Revere, but probably not Molly Pitcher, Lydia Darragh, or Deborah Sampson. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to demonstrate not only the lack of inclusivity of women in the memory of the Revolutionary War, but also why the women that did achieve recognition surpassed the rest. Women contributed to the war effort in multiple ways, including serving as cooks, laundresses, nurses, spies, and even as soldiers on the battlefields. Unfortunately, due to the large number of female participants, it would be impossible to include the narratives of all of the women involved in the war. -

The Female Review

The Female Review wife and children; soon after, mother Deborah Bradford Sampson The Female Review (1797) put five-year-old Deborah out to service in various Massachusetts Herman Mann households. An indentured servant until age eighteen, Sampson, now a “masterless woman,” became a weaver (“one of the very few androgynous trades in New England,” notes biographer Text prepared by Ed White (Tulane University) and Duncan Faherty (Queens College and the CUNY Graduate Center). We want to thank Paul Erickson and Alfred Young [40]), then a rural schoolteacher, then, near age the American Antiquarian Society for their tremendous support, and Jodi twenty-one, a soldier in the Continental Army (37). Donning Schorb (University of Florida) for contributing the following introduction. men’s clothes (not for the first time, as it turns out) and adopting the generic name “Robert Shurtliff,” the soldier fought in several skirmishes, suffered battle injuries (to either the groin or upper Mann Seeking Woman: body), and was eventually promoted to serving as “waiter” (an Reading The Female Review officer’s orderly) to brigadier general John Paterson. Sampson’s military career has been most carefully Jodi Schorb reconstructed by Alfred F. Young in Masquerade: The Life and Times of Deborah Sampson, Continental Soldier. Although The Female Review In the wake of the American Revolution and beyond, claims Sampson/Shurtliff enlisted in 1781 and fought at the Battle Deborah Sampson was both celebrity and enigma, capturing the of Yorktown (September-October, 1781), Sampson/Shurtliff 1 imagination of a nation that had successfully won their actually served in the Continental Army from May, 1782 until independence from England. -

George Bush - the Unauthorized Biography by Webster Griffin Tarpley and Anton Chaitkin

George Bush - The Unauthorized Biography by Webster Griffin Tarpley and Anton Chaitkin Introduction AMERICAN CALIGULA 47,195 bytes THE HOUSE OF BUSH: BORN IN A 1 33,914 bytes BANK 2 THE HITLER PROJECT 55,321 bytes RACE HYGIENE: THREE BUSH 3 51,987 bytes FAMILY ALLIANCES THE CENTER OF POWER IS IN 4 51,669 bytes WASHINGTON 5 POPPY AND MOMMY 47,684 bytes 6 BUSH IN WORLD WAR II 36,692 bytes SKULL AND BONES: THE RACIST 7 56,508 bytes NIGHTMARE AT YALE 8 THE PERMIAN BASIN GANG 64,269 bytes BUSH CHALLENGES 9 YARBOROUGH FOR THE 110,435 bytes SENATE 10 RUBBERS GOES TO CONGRESS 129,439 bytes UNITED NATIONS AMBASSADOR, 11 99,842 bytes KISSINGER CLONE CHAIRMAN GEORGE IN 12 104,415 bytes WATERGATE BUSH ATTEMPTS THE VICE 13 27,973 bytes PRESIDENCY, 1974 14 BUSH IN BEIJING 53,896 bytes 15 CIA DIRECTOR 174,012 bytes 16 CAMPAIGN 1980 139,823 bytes THE ATTEMPTED COUP D'ETAT 17 87,300 bytes OF MARCH 30, 1981 18 IRAN-CONTRA 140,338 bytes 19 THE LEVERAGED BUYOUT MOB 67,559 bytes 20 THE PHONY WAR ON DRUGS 26,295 bytes 21 OMAHA 25,969 bytes 22 BUSH TAKES THE PRESIDENCY 112,000 bytes 23 THE END OF HISTORY 168,757 bytes 24 THE NEW WORLD ORDER 255,215 bytes 25 THYROID STORM 138,727 bytes George Bush: The Unauthorized Biography by Webster Griffin Tarpley and Anton Chaitkin With this issue of the New Federalist, Vol. V, No. 39, we begin to serialize the book, "George Bush: The Unauthorized Biography," by Webster Griffin Tarpley and Anton Chaitkin. -

Mission 3 Part 5 Review Questions Answer Key FINAL

TEACHER’S GUIDE Review Questions Answer Key Part 5: Battle of the Greasy Grass MISSION 3: “A Cheyenne Odyssey” A NOTE TO THE EDUCATOR: The purpose of these questions is to check the students’ understanding of the action of the game and the history embedded in that action. Since the outcome of gameplay can vary depending on the choices the student makes, the answers to the questions might also vary. Some students might learn information later than others, or not at all. If you choose to discuss students’ responses as a whole group, information can be shared among all your “Little Foxes.” There may be more questions here than you want your students to answer in one sitting or in one evening. In that case, choose the questions you feel are most essential for their understanding of Part 5. Feel free to copy the following pages of this activity for your students. If you are not planning to have your students write the answers to the questions, you’ll need to modify the directions. TEACHER’S GUIDE Review Questions Answer Key Part 5: Battle of the Greasy Grass MISSION 3: “A Cheyenne Odyssey” Name: ___________________________ Date:_____________________ Directions: After you play Part 5, read and answer these questions from the point of view of your character, Little Fox. You may not know all the answers, so do the best you can. Write in complete sentences and proofread your work. 1) At the beginning of Part 5, Little Fox’s band decides to fight alongside the other Cheyenne and Lakota warriors. -

Nordic Narratives of the Second World War : National Historiographies Revisited

Nordic Narratives of the Second World War : National Historiographies Revisited Stenius, Henrik; Österberg, Mirja; Östling, Johan 2011 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Stenius, H., Österberg, M., & Östling, J. (Eds.) (2011). Nordic Narratives of the Second World War : National Historiographies Revisited. Nordic Academic Press. Total number of authors: 3 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 nordic narratives of the second world war Nordic Narratives of the Second World War National Historiographies Revisited Henrik Stenius, Mirja Österberg & Johan Östling (eds.) nordic academic press Nordic Academic Press P.O. Box 1206 SE-221 05 Lund, Sweden [email protected] www.nordicacademicpress.com © Nordic Academic Press and the authors 2011 Typesetting: Frederic Täckström www.sbmolle.com Cover: Jacob Wiberg Cover image: Scene from the Danish movie Flammen & Citronen, 2008.