124 Warfare Actions of the Large Romanian Military

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

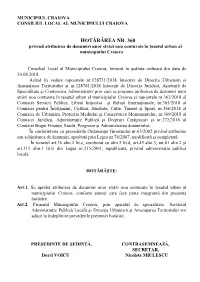

Strada Radu Calomfirescu HCL Nr

MUNICIPIUL CRAIOVA CONSILIUL LOCAL AL MUNICIPIULUI CRAIOVA HOTĂRÂREA NR. 360 privind atribuirea de denumiri unor străzi nou conturate în țesutul urban al municipiului Craiova Consiliul Local al Municipiului Craiova, întrunit în şedinţa ordinară din data de 30.08.2018. Având în vedere rapoartele nr.128731/2018 întocmit de Direcţia Urbanism şi Amenajarea Teritoriului și nr.128761/2018 întocmit de Direcția Juridică, Asistență de Specialitate și Contencios Administrativ prin care se propune atribuirea de denumiri unor străzi nou conturate în țesutul urban al municipiului Craiova și rapoartele nr.362/2018 al Comisiei Servicii Publice, Liberă Iniţiativă şi Relaţii Internaţionale, nr.365/2018 al Comisiei pentru Învăţământ, Cultură, Sănătate, Culte, Tineret şi Sport, nr.366/2018 al Comisiei de Urbanism, Protecţia Mediului şi Conservarea Monumentelor, nr.369/2018 al Comisiei Juridică, Administraţie Publică şi Drepturi Cetăţeneşti şi nr.372/2018 al Comisiei Buget Finanţe, Studii, Prognoze i Administrarea domeniului; În conformitate cu prevederile Ordonanţei Guvernului nr.63/2002 privind atribuirea sau schimbarea de denumiri, aprobată prin Legea nr.76/2007, modificată i completată; În temeiul art.36 alin.2 lit.c, coroborat cu alin.5 lit.d, art.45 alin.3, art.61 alin.2 şi art.115 alin.1 lit.b din Legea nr.215/2001, republicată, privind administraţia publică locală; HOTĂRĂŞTE: Art.1. Se aprobă atribuirea de denumiri unor străzi nou conturate în țesutul urban al municipiului Craiova, conform anexei care face parte integrantă din prezenta hotărâre. Art.2. Primarul Municipiului Craiova, prin aparatul de specialitate: Serviciul Administraţie Publică Locală şi Direcţia Urbanism şi Amenajarea Teritoriului vor aduce la îndeplinire prevederile prezentei hotărâri. -

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930S

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Ariel Mae Lambe All rights reserved ABSTRACT Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe This dissertation shows that during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) diverse Cubans organized to support the Spanish Second Republic, overcoming differences to coalesce around a movement they defined as antifascism. Hundreds of Cuban volunteers—more than from any other Latin American country—traveled to Spain to fight for the Republic in both the International Brigades and the regular Republican forces, to provide medical care, and to serve in other support roles; children, women, and men back home worked together to raise substantial monetary and material aid for Spanish children during the war; and longstanding groups on the island including black associations, Freemasons, anarchists, and the Communist Party leveraged organizational and publishing resources to raise awareness, garner support, fund, and otherwise assist the cause. The dissertation studies Cuban antifascist individuals, campaigns, organizations, and networks operating transnationally to help the Spanish Republic, contextualizing these efforts in Cuba’s internal struggles of the 1930s. It argues that both transnational solidarity and domestic concerns defined Cuban antifascism. First, Cubans confronting crises of democracy at home and in Spain believed fascism threatened them directly. Citing examples in Ethiopia, China, Europe, and Latin America, Cuban antifascists—like many others—feared a worldwide menace posed by fascism’s spread. -

George Bush - the Unauthorized Biography by Webster Griffin Tarpley and Anton Chaitkin

George Bush - The Unauthorized Biography by Webster Griffin Tarpley and Anton Chaitkin Introduction AMERICAN CALIGULA 47,195 bytes THE HOUSE OF BUSH: BORN IN A 1 33,914 bytes BANK 2 THE HITLER PROJECT 55,321 bytes RACE HYGIENE: THREE BUSH 3 51,987 bytes FAMILY ALLIANCES THE CENTER OF POWER IS IN 4 51,669 bytes WASHINGTON 5 POPPY AND MOMMY 47,684 bytes 6 BUSH IN WORLD WAR II 36,692 bytes SKULL AND BONES: THE RACIST 7 56,508 bytes NIGHTMARE AT YALE 8 THE PERMIAN BASIN GANG 64,269 bytes BUSH CHALLENGES 9 YARBOROUGH FOR THE 110,435 bytes SENATE 10 RUBBERS GOES TO CONGRESS 129,439 bytes UNITED NATIONS AMBASSADOR, 11 99,842 bytes KISSINGER CLONE CHAIRMAN GEORGE IN 12 104,415 bytes WATERGATE BUSH ATTEMPTS THE VICE 13 27,973 bytes PRESIDENCY, 1974 14 BUSH IN BEIJING 53,896 bytes 15 CIA DIRECTOR 174,012 bytes 16 CAMPAIGN 1980 139,823 bytes THE ATTEMPTED COUP D'ETAT 17 87,300 bytes OF MARCH 30, 1981 18 IRAN-CONTRA 140,338 bytes 19 THE LEVERAGED BUYOUT MOB 67,559 bytes 20 THE PHONY WAR ON DRUGS 26,295 bytes 21 OMAHA 25,969 bytes 22 BUSH TAKES THE PRESIDENCY 112,000 bytes 23 THE END OF HISTORY 168,757 bytes 24 THE NEW WORLD ORDER 255,215 bytes 25 THYROID STORM 138,727 bytes George Bush: The Unauthorized Biography by Webster Griffin Tarpley and Anton Chaitkin With this issue of the New Federalist, Vol. V, No. 39, we begin to serialize the book, "George Bush: The Unauthorized Biography," by Webster Griffin Tarpley and Anton Chaitkin. -

Downloads of Technical Information

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Nuclear Spaces: Simulations of Nuclear Warfare in Film, by the Numbers, and on the Atomic Battlefield Donald J. Kinney Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES NUCLEAR SPACES: SIMULATIONS OF NUCLEAR WARFARE IN FILM, BY THE NUMBERS, AND ON THE ATOMIC BATTLEFIELD By DONALD J KINNEY A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Donald J. Kinney defended this dissertation on October 15, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Ronald E. Doel Professor Directing Dissertation Joseph R. Hellweg University Representative Jonathan A. Grant Committee Member Kristine C. Harper Committee Member Guenter Kurt Piehler Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Morgan, Nala, Sebastian, Eliza, John, James, and Annette, who all took their turns on watch as I worked. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee, Kris Harper, Jonathan Grant, Kurt Piehler, and Joseph Hellweg. I would especially like to thank Ron Doel, without whom none of this would have been possible. It has been a very long road since that afternoon in Powell's City of Books, but Ron made certain that I did not despair. Thank you. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract..............................................................................................................................................................vii 1. -

The World War Two Allied Economic Warfare: the Case of Turkish Chrome Sales

The World War Two Allied Economic Warfare: The Case of Turkish Chrome Sales Inaugural-Dissertation in der Philosophischen Fakultät und Fachbereich Theologie der Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen Nürnberg Vorgelegt von Murat Önsoy Aus der Türkei D29 Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 15 April 2009 Dekan: Universitätsprofessor Dr. Jens Kulenkampff. Erstgutachter: Universitätsprofessor Dr. Thomas Philipp Zweitgutachter: Universitätsprofessor Dr. Şefik Alp Bahadır ACKNOWLEDGMENTS An interesting coincidence took place in the first year of my PhD study, I would like to share it here. Soon after I moved to Erlangen, I started thinking over my PhD thesis topic. I was searching for an appropriate subject. Turkish Chrome Sales was one of the few topics that I had in my mind. One day, I went to my Doktorvater Prof. Thomas Philipp’s office and discussed the topics with him. We decided to postpone the decision a few days while I wanted to consider the topics one last time and do the final elimination. Afterwards I went to the cafeteria of the Friedrich Alexander University to have lunch. After the lunch, just before I left the cafeteria building, I recognized somebody speaking Turkish and reflexively turned around. He was a Turkish guest worker with a large thick moustache; I paid attention to his name tag for a second. His name was Krom, the Turkish word for chrome, since, for the first time in my life I was meeting someone with the name Krom I asked him about his name. Perhaps he is the only person with this name in Turkey. He told me that, this name was given by his father, who was a worker of a chrome mine in Central Anatolia and that day, when Mr. -

Delegation Statements

Delegation Statements AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE Statement by David A. Harris EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR To the Delegates to the Washington Conference on Holocaust- Era Assets: As one of the non-governmental organizations privileged to be accredited to the Conference, we join in expressing our hope that this historic gathering will fulfill the ambitious and worthy goals set for it. The effort to identify the compelling and complex issues of looted assets from the Second World War, and to consult on the most appropriate and expeditious means of addressing and resolving these issues, offers a beacon of light at the end of a very long and dark tunnel for Holocaust survivors, for the descendants of those who perished in the flames, for the vibrant Jewish communities which were destroyed, and for all who fell victim to the savagery and rapacity of those horrific times. We are pleased as well that, in addition to discussion of these enormously important topics, the Conference will also take up the matter of Holocaust education, for, in the end, this can be our permanent legacy to future generations. We hope that the Conference will reach a consensus on the need for enhanced international consultation, with the aim of encouraging more widespread teaching of the Holocaust in national school systems. Moreover, we commend those nations that have already taken impressive steps in this regard. Not only can teaching of the Holocaust provide young people with a better insight into the darkest chapter in this century's history, but, ultimately, it can serve to strengthen their commitment to fundamental principles of human decency, mutual understanding and tolerance – all of 146 WASHINGTON CONFERENCE ON HOLOCAUST-ERA ASSETS which are so necessary if we are to have any chance of creating a brighter future. -

World War Ii Veteran’S Committee, Washington, Dc Under a Generous Grant from the Dodge Jones Foundation 2

W WORLD WWAR IIII A TEACHING LESSON PLAN AND TOOL DESIGNED TO PRESERVE AND DOCUMENT THE WORLD’S GREATEST CONFLICT PREPARED BY THE WORLD WAR II VETERAN’S COMMITTEE, WASHINGTON, DC UNDER A GENEROUS GRANT FROM THE DODGE JONES FOUNDATION 2 INDEX Preface Organization of the World War II Veterans Committee . Tab 1 Educational Standards . Tab 2 National Council for History Standards State of Virginia Standards of Learning Primary Sources Overview . Tab 3 Background Background to European History . Tab 4 Instructors Overview . Tab 5 Pre – 1939 The War 1939 – 1945 Post War 1945 Chronology of World War II . Tab 6 Lesson Plans (Core Curriculum) Lesson Plan Day One: Prior to 1939 . Tab 7 Lesson Plan Day Two: 1939 – 1940 . Tab 8 Lesson Plan Day Three: 1941 – 1942 . Tab 9 Lesson Plan Day Four: 1943 – 1944 . Tab 10 Lesson Plan Day Five: 1944 – 1945 . Tab 11 Lesson Plan Day Six: 1945 . Tab 11.5 Lesson Plan Day Seven: 1945 – Post War . Tab 12 3 (Supplemental Curriculum/American Participation) Supplemental Plan Day One: American Leadership . Tab 13 Supplemental Plan Day Two: American Battlefields . Tab 14 Supplemental Plan Day Three: Unique Experiences . Tab 15 Appendixes A. Suggested Reading List . Tab 16 B. Suggested Video/DVD Sources . Tab 17 C. Suggested Internet Web Sites . Tab 18 D. Original and Primary Source Documents . Tab 19 for Supplemental Instruction United States British German E. Veterans Organizations . Tab 20 F. Military Museums in the United States . Tab 21 G. Glossary of Terms . Tab 22 H. Glossary of Code Names . Tab 23 I. World War II Veterans Questionnaire . -

Long-Running Rum War Between Bacardi, Pernod Ricard Shifts To

Vol. 15, No. 5 May 2007 www.cubanews.com In the News Long-running rum war between Bacardi, Pernod Ricard shifts to federal courts Fidel’s recovery Despite his improving health, don’t expect BY ANA RADELAT and politics between the powerful Bacardí exile family and the Castro government, which has a Fidel to return to power ...............Page 3 fter bouncing from the Patent and Trade- mark Office to federal courts to Congress willing ally in Pernod Ricard. A to the World Trade Organization, the bit- “I’m certain there is some long-term animosi- Phone home ter fight over the Havana Club trademark has ty between the Bacardi family and the Cuban U.S. carriers pay Cuba’s Etecsa $102m to finally shifted back to the courtroom. regime. They have long memories and under- The combatants are Havana Club Holdings standably so,” said Mark Orr, vice-president of complete long-distance calls ........Page 4 (HCH) — a 50-50 venture between the Cuban Pernod Ricard North America. “But I’ve also government and French drinks conglomerate seen that the French are stubborn and have Vitral closes down Pernod Ricard — and Bacardi, the giant spirits long memories, too.” Feisty Catholic newspaper in Pinar del Rió empire owned by Cuban exiles whose property Huge amounts of money have been spent on was expropriated by the Castro government in legal fees over the Havana Club name and there publishes its last issue ..................Page 5 the 1960s. is no indication that spending on lawsuits will Federal district courts in Washington and stop anytime soon. -

Cartographic World War II Records Guide

Cartographic World War II Records Guide This guide was compiled from various descriptions from our online catalog at catalog.archives.gov. The following description fields are included: Series Title Dates - Some dates include both when the series was compiled or maintained as well as the time period that the records cover. NAID (National Archives Identifier) - This is a unique identifier that allows us locate materials in our holdings. A series description (scope and content) is included for each series entry. Type of archival materials - This field describes what type of records the series includes. Arrangement - This field provides you with information on how the records have been arranged and organized. This may help you understand what kind of information is needed to pull the records. Finding aid - If there is another finding that we can provide you to help locate specific folders, boxes or individual records, it will be listed here. All of these finding aids will be available as a paper copy and/or as a digital file in our research room. Access and use restrictions - If there are any access or use restrictions on the records, they will be listed and explained here. Extent - This notes how many items or folders are included in the series. Digitized - This field will tell you if any of the records in the series are digitized and available in our catalog. Any digitized records are available at catalog.arhcives.gov by entering the provided NAID in the search bar. Selection note: The selected series were chosen to be included based on their research value pertaining to World War II and the particular time period of 1939 - 1945. -

Remembering Manchukuo………………………………………………..319

Utopia/Dystopia: Japan’s Image of the Manchurian Ideal by Kari Leanne Shepherdson-Scott Department of Art, Art History, and Visual Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Gennifer Weisenfeld, Supervisor ___________________________ David Ambaras ___________________________ Mark Antliff ___________________________ Stanley Abe Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History, and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 i v ABSTRACT Utopia/Dystopia: Japan’s Image of the Manchurian Ideal by Kari Leanne Shepherdson-Scott Department of Art, Art History, and Visual Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Gennifer Weisenfeld, Supervisor ___________________________ David Ambaras ___________________________ Mark Antliff ___________________________ Stanley Abe An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History, and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 Copyright by Kari Leanne Shepherdson-Scott 2012 Abstract This project focuses on the visual culture that emerged from Japan’s relationship with Manchuria during the Manchukuo period (1932-1945). It was during this time that Japanese official and popular interest in the region reached its peak. Fueling the Japanese attraction and investment in this region were numerous romanticized images of Manchuria’s bounty and space, issued to bolster enthusiasm for Japanese occupation and development of the region. I examine the Japanese visual production of a utopian Manchuria during the 1930s and early 1940s through a variety of interrelated media and spatial constructions: graphic magazines, photography, exhibition spaces, and urban planning. -

CONGRESSIO:NAL RECORD-SENATE ~Llrch-12

150. CONGRESSIO:NAL RECORD-SENATE ~llRCH-12 SEN.ATE Hurrah! hurrah for Dawe ! Hurrah . hurrah for this high-minded man! THURSDAY, lTfarch 12, 19CJ5 And when bis statue is placed on bio-h Under the dome of the Capitol ky, "' ' (Legislati're day ot T'uesclay, March 10, 1925) The great senatorial temple of fame, There with the gloriou general's name The Senate met in open executive e~sion at 12 o'clock merid Be it aid, in letters both bold and brioobt ian, on the expiration of the recess. "Ob, Hell an' Maria, be bas lost us the ftght." The VICE PRESIDENT. The Chair lays before the Senate the treaty with Cuba relative to the Isle of Pine , on which the [Laughter.] enator from New York [1\Ir. CoPELAND] i entitled to the floor. The VICE PRESIDEN"T. The Chair can not refrain f1·om Ur. NORRIS. :Mr. Pre ident-- expre ·ing his appreciation of the delicate tribute. l\Ir. COPEL~"'D. I yield to the Senator from Nehra ka. Mr. NEELY. Mr. Pre. iclent, there seems to be a conflict of :Mr. NORRIS. I will ay to the Senator from New York t11at opinion as to how far the Vice President was from the Senate I would like to have the floor in my own right for about three Chamber last Tue day at the critical moment when his -,ote minutes. would ha-,e confirmed the Pre. id.ent' nomination of Mr. :Mr. COPEJJA1\1J). I am o-lad to yield to the Senator if it may Oharle. -

A NATO Strategy for Security in the Black Sea Region

Atlantic Council BRENT SCOWCROFT CENTER ON INTERNATIONAL SECURITY ISSUE BRIEF A NATO Strategy for Security in the Black Sea Region SEPTEMBER 2016 STEVEN HORRELL he Black Sea region is a crossroads, an intersection between Europe and the Middle East, from the eastern Balkans to the South Caucasus. Like many such points of intersection, it is often a friction point. This is very much the case in the current Tgeopolitical environment of growing confrontation between Russia and the West. Any friction there will almost certainly involve NATO nations and the Alliance’s interests, with three NATO states on the Black Sea and several NATO partners on the Black Sea and throughout the region. Maintaining a dominant role in the Black Sea region forms an important element of Russian strategy; however, Western policymakers have been deficient in giving strategic attention to the Black Sea region in recent years. That may be changing. In addition to emphasizing collective defense and deterrence, the final communiqué of the NATO Warsaw Summit highlighted the importance of the Black Sea region: “We condemn Russia’s ongoing and wide-ranging military build-up in Crimea, and are concerned by Russia’s efforts and stated plans for further military build-up in the Black Sea region.”1 NATO has the opportunity and responsibility to move forward from the statements of the Warsaw Summit. The Black Sea region needs The Brent Scowcroft Center’s NATO as a steadying influence, and NATO needs to address the Transatlantic Security Alliance’s interests in the region. This issue brief offers the framework Initiative brings together top of a NATO strategy to ensure stability in this critical area; it expands policymakers, government and military officials, business on the communiqué’s objectives for security in that region, posits an leaders, and experts from Europe approach, and recommends actions to improve stability and security in and North America to share the Black Sea region.