Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bach Christmas Oratorio Prog Notes

Johann Sebastian Bach Christmas Oratorio Programme Notes Johann Sebastian Bach’s Christmas Oratorio was composed in 1734. The title page of the printed libretto, prepared for the congregation, notes “Oratorio performed over the holy festival of Christmas in the two chief churches in Leipzig.” The oratorio was divided into six parts, each part to be performed at one of the six services held during the Lutheran celebration of the Twelve Nights of Christmas. Parts I, II, IV and VI were each performed twice, at St. Thomas and St. Nicholas in alternate morning and afternoon services. Parts III and V, written for days of lesser significance in the festival, were performed only once at St. Nicholas. The music would have served as the “principal music” for the day, replacing the cantata that would otherwise have been performed. The structure of the Christmas Oratorio is similar to that of Bach’s Passions: Bach presents a dramatic rendering of a biblical text, largely in the form of secco recitative (recitative with simple continuo accompaniment) sung by an Evangelist, and adds to it comments and reflections of both an individual and congregational nature, in the form of arias, choruses, and chorales. The biblical text in question is the story of the birth of Jesus through to the arrival of the three Wise Men, drawn from the Gospels according to Luke and Matthew. The narrative is by its very nature less dramatic than that of the Passions, so Bach introduces a number of arioso passages: accompanied recitatives in which the spectator enters the story. The bass soloist, for example, speaks to the shepherds, and the alto to Herod and to the Wise Men, outside the narrative proper, yet intimately involved with it. -

May 2 Order of Worship

FIRST BAPTIST CHURCH Historic | Liturgical | Vibrant FIFTH SUNDAY OF EASTERTIDE May 2, 2021 at 11:00 am WE GATHER TO PRAISE GOD Music Notes CHIMING OF THE HOUR Much of the music used in today’s worship service will be excerpts from “Der WELCOME Rev. Katie Callaway & Rev. John Callaway Himmel lacht! Die Erde jubilieret” (Heaven Laughs! Earth Exults) by INVOCATION Johann Sebastian Bach. This work is Bach’s 31st PRELUDE - “Sonata” from Cantata No. 31 by Johann Sebastian Bach church cantata and was North Carolina Baroque Orchestra written for the first day of the Easter season. It was first performed in CALL TO WORSHIP - Psalm 22:25-31 Ellen Davis, Lay Reader Weimar, Germany, on April 21, 1715 and later HYMN - “Christ Is Risen, Shout Hosanna” Tune: HYMN TO JOY reworked for performances in Leipzig. The work is scored for five Christ is risen! Shout hosanna! part choir, large Celebrate this day of days! orchestra, and soprano, tenor, and bass soloists. Christ is risen! Hush in wonder: All creation is amazed. In the desert all surrounding, Guest Musicians See, a spreading tree has grown. Healing leaves of grace abounding Today we welcome the Bring a taste of love unknown. choir of Wake Forest University from Winston Salem, NC. They are Christ is risen! Raise your spirits under the direction of Dr. From the caverns of despair. Christopher Gilliam and Walk with gladness in the morning. accompanied by the North See what love can do and dare. Carolina Baroque Orchestra. The choral Drink the wine of resurrection, program at Wake Not a servant, but a friend. -

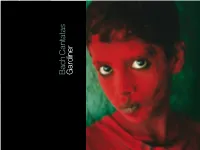

B Ach C Antatas G Ardiner

Johann Sebastian Bach 1685-1750 Cantatas Vol 26: Long Melford SDG121 COVER SDG121 CD 1 67:39 For Whit Sunday Erschallet, ihr Lieder, erklinget, ihr Saiten! BWV 172 Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort halten I BWV 59 Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort halten II BWV 74 O ewiges Feuer, o Ursprung der Liebe BWV 34 Lisa Larsson soprano, Nathalie Stutzmann alto Derek Lee Ragin alto, Christoph Genz tenor Panajotis Iconomou bass C CD 2 47:58 For Whit Monday M Erhöhtes Fleisch und Blut BWV 173 Also hat Gott die Welt geliebt BWV 68 Y Ich liebe den Höchsten von ganzem Gemüte BWV 174 K Lisa Larsson soprano, Nathalie Stutzmann alto Christoph Genz tenor, Panajotis Iconomou bass The Monteverdi Choir The English Baroque Soloists John Eliot Gardiner Live recordings from the Bach Cantata Pilgrimage Holy Trinity, Long Melford, 11 & 12 June 2000 Soli Deo Gloria Volume 26 SDG 121 P 2006 Monteverdi Productions Ltd C 2006 Monteverdi Productions Ltd www.solideogloria.co.uk Edition by Reinhold Kubik, Breitkopf & Härtel Manufactured in Italy LC13772 8 43183 01212 1 26 SDG 121 Bach Cantatas Gardiner Bach Cantatas Gardiner CD 1 67:39 For Whit Sunday The Monteverdi Choir The English Flutes 1-7 18:31 Erschallet, ihr Lieder, erklinget, ihr Saiten! BWV 172 Baroque Soloists Marten Root Sopranos Rachel Beckett 8-12 11:38 Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort halten I BWV 59 Suzanne Flowers First Violins 13-20 20:34 Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort halten II BWV 74 Gillian Keith Kati Debretzeni Oboes Emma Preston-Dunlop Penelope Spencer Michael Niesemann 21-25 16:45 -

Bach and the Rationalist Philosophy of Wolff, Leibniz and Spinoza,” 60-71

Chapter 1 On the Musically Theological in Bach’s Cantatas From informal Internet discussion groups to specialized aca demic conferences and publications, an ongoing debate has raged on whether J. S. Bach ought to be considered a purely artistic or also a religious figure.^ A recently formed but now disbanded group of scholars, the Internationale Arbeitsgemeinschaft fiir theologische Bachforschung, made up mostly of German theologians, has made significant contributions toward understanding the religious con texts of Bach’s liturgical music.^ These writers have not entirely captured the attention or respect of the wider world of Bach 1. For the academic side, the most influential has been Friedrich Blume, “Umrisse eines neuen Bach-Bildes,” Musica 16 (1962): 169-176, translated as “Outlines of a New Picture of Bach,” Music and Letters 44 (1963): 214-227. The most impor tant responses include Alfred Durr, “Zum Wandel des Bach-Bildes: Zu Friedrich Blumes Mainzer Vortrag,” Musik und Kirche 32 (1962): 145-152; see also Friedrich Blume, “Antwort von Friedrich Blume,” Musik und Kirche 32 (1962): 153-156; Friedrich Smend, “Was bleibt? Zu Friedrich Blumes Bach-Bild,” DerKirchenmusiker 13 (1962): 178-188; and Gerhard Herz, “Toward a New Image of Bach,” Bach 1, no. 4 (1970): 9-27, and Bach 2, no. 1 (1971): 7-28 (reprinted in Essays on J. S. Bach [Ann Arbor: UMI Reseach Press, 1985], 149-184). 2. For a convenient list of the group’s main publications, see Daniel R. Melamed and Michael Marissen, An Introduction to Bach Studies (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 15. For a full bibliography to 1996, see Renate Steiger, ed., Theologische Bachforschung heute: Dokumentation und Bibliographie der Intemationalen Arbeitsgemeinschaft fiir theologische Bachforschung 1976-1996 (Glienicke and Berlin: Galda and Walch, 1998), 353-445. -

Christmas Oratorio

Reflections on Bach’s “Christmas Oratorio” by John Harbison Composer John Harbison, whose ties to Boston’s cultural and educational communities are longstanding, celebrates his 80th birthday on December 20, 2018. To mark this birthday, the BSO will perform his Symphony No. 2 on January 10, 11, and 12 at Symphony Hall, and the Boston Symphony Chamber Players perform music of Harbison and J.S. Bach on Sunday afternoon, January 13, at Jordan Hall. The author of a new book entitled “What Do We Make of Bach?–Portraits, Essays, Notes,” Mr. Harbison here offers thoughts on Bach’s “Christmas Oratorio.” Andris Nelsons’ 2018 performances of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio are the Boston Symphony’s first since 1950, when Charles Munch was the orchestra’s music director. Munch may have been the last BSO conductor for whom Bach’s music remained a natural and substantial part of any season. In the 1950s the influence of Historically Informed Practice (HIP) was beginning to be felt. Large orchestras and their conductors began to draw away from 18th-century repertoire, feeling themselves too large, too unschooled in stylistic issues. For Charles Munch, Bach was life-blood. I remember hearing his generous, spacious performance of Cantata 4, his monumental reading of the double-chorus, single-movement Cantata 50. Arriving at Tanglewood as a Fellow in 1958, opening night in the Theatre-Concert Hall, there was Munch’s own transcription for string orchestra of Bach’s complete Art of Fugue! This was a weird and glorious experience, a two-hour journey through Bach’s fugue cycle that seemed a stream of sublime, often very unusual harmony, seldom articulated as to line or sectional contrast. -

The Historical Figures of the Birthday Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Theses Theses and Dissertations 5-15-2010 The iH storical Figures of the Birthday Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach Marva J. Watson Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Watson, Marva J., "The iH storical Figures of the Birthday Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach" (2010). Theses. Paper 157. This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORICAL FIGURES OF THE BIRTHDAY CANTATAS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH by Marva Jean Watson B.M., Southern Illinois University, 1980 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Music Degree School of Music in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2010 THESIS APPROVAL THE HISTORICAL FIGURES OF THE BIRTHDAY CANTATAS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH By Marva Jean Watson A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in the field of Music History and Literature Approved by: Dr. Melissa Mackey, Chair Dr. Pamela Stover Dr. Douglas Worthen Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 2, 2010 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF MARVA JEAN WATSON, for the Master of Music degree in Music History and Literature, presented on 2 April 2010, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: THE HISTORICAL FIGURES OF THE BIRTHDAY CANTATAS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. -

The Bach Experience

MUSIC AT MARSH CHAPEL 10|11 Scott Allen Jarrett Music Director Sunday, January 30, 2011 – 9:45A.M. The Bach Experience BWV 171: ‘Gott, wie dein Name, so ist auch dein Ruhm’ Marsh Chapel Choir and Collegium Scott Allen Jarrett, DMA, presenting BWV 171: ‘Gott, wie dein Name, so ist auch dein Ruhm’ - Composed and performed as early as January 1, 1729 for New Year or Feast of the Circumcision; first movement appears later in the Credo of the B Minor Mass: ‘Patrem omnipotentem’ - Scored for three trumpets, timpani, two oboes, and strings; solos for soprano, alto, tenor and bass - Central message is the name of Christ – the purity of Jesus’ name as a means of intercession, power and strength - The libretto is compiled and authored by Picander, drawing on Psalm 48:10 for the opening movement. - Duration: about 21 minutes Some helpful German words to know . Ruhm fame Wolken clouds Süsser sweet Trost comfort Ruh rest or peace Kreuze cross lauf laugh verfolget persecuted Heliand savior See the morning’s bulletin for a complete translation of Cantata 171. Some helpful music terms to know . Continuo – generally used in Baroque music to indicate the group of instruments who play the bass line, and thereby, establish harmony; usually includes the keyboard instrument (organ or harpsichord), and a combination of cello and bass, and sometimes bassoon. Da capo – literally means ‘the head’ in Italian; in musical application this means to return to the beginning of the music. As a form (i.e. ‘da capo’ aria), it refers to a style in which a middle section, usually in a different tonal area or key, is followed by an exact restatement of the opening section: ABA. -

Bach Choir Presents Cantatas by Bach and a Work by Italian Composer Ottorino Respighi for Its Christmas Concerts

Bach Choir presents cantatas by Bach and a work by Italian composer Ottorino Respighi for its Christmas concerts The Bach Choir will perform present Ottorino Respighi's Laud to the Nativity and J.S. Bach's festive Cantata 63 and Cantata 36 at its Christmas concerts Dec. 8 and 9. Contributed Photo: Don Schroder Steve Siegel Special to The Morning Call Sometimes music is most moving when it evokes the past. Familiar works that engage listeners in emotional time-travel include Vaughan Williams’ “Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis” and much of the music of Arvo Part. Ottorino Respighi is another whose music is frequently steeped in the vivid imagery of the Italian Renaissance and Middle Ages. That’s especially true of his "Lauda per la Nativita del Signore” (Laud to the Nativity), his sole sacred choral piece. Respighi’s richly beautiful yet rarely heard work, and J.S. Bach’s festive Cantata 63, “Christen, atzet diesen Tag” (Christians all, this happy day) and Cantata 36, “Schwingt freudig euch empor” Soar joyfully aloft) are the featured works in this year’s Bach Choir of Bethlehem Christmas Concerts. Bach Choir director Greg Funfgeld will lead the Bach Choir and Festival Orchestra in its Christmas concerts on Nov. 8 and 9. The programs are Saturday at the First Presbyterian Church of Allentown, repeated Sunday at the First Presbyterian Church of Bethlehem. The Bach Choir and Bach Festival Orchestra will be led by Bach Choir artistic director Greg Funfgeld and joined by soprano soloists Ellen McAteer and Fiona Gillespie, countertenor Daniel Taylor, tenor Charles Blady and baritone Christopheren Nomura. -

Tifh CHORALE CANTATAS

BACH'S TREATMIET OF TBE CHORALi IN TIfh CHORALE CANTATAS ThSIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Floyd Henry quist, B.A. Denton, Texas August, 1950 N. T. S. C. LIBRARY CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. ...... .... v PIEFACE . vii Chapter I. ITRODUCTION..............1 II. TECHURCH CANTATA.............T S Origin of the Cantata The Cantata in Germany Heinrich Sch-Utz Other Early German Composers Bach and the Chorale Cantata The Cantata in the Worship Service III. TEEHE CHORAI.E . * , . * * . , . , *. * * ,.., 19 Origin and Evolution The Reformation, Confessional and Pietistic Periods of German Hymnody Reformation and its Influence In the Church In Musical Composition IV. TREATENT OF THED J1SIC OF THE CHORAIJS . * 44 Bach's Aesthetics and Philosophy Bach's Musical Language and Pictorialism V. TYPES OF CHORAJETREATENT. 66 Chorale Fantasia Simple Chorale Embellished Chorale Extended Chorale Unison Chorale Aria Chorale Dialogue Chorale iii CONTENTS (Cont. ) Chapter Page VI. TREATMENT OF THE WORDS OF ThE CHORALES . 103 Introduction Treatment of the Texts in the Chorale Cantatas CONCLUSION . .. ................ 142 APPENDICES * . .143 Alphabetical List of the Chorale Cantatas Numerical List of the Chorale Cantatas Bach Cantatas According to the Liturgical Year A Chronological Outline of Chorale Sources The Magnificat Recorded Chorale Cantatas BIBLIOGRAPHY . 161 iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIO1S Figure Page 1. Illustration of the wave motive from Cantata No. 10e # * * # s * a * # . 0 . 0 . 53 2. Illustration of the angel motive in Cantata No. 122, - - . 55 3. Illustration of the motive of beating wings, from Cantata No. -

Bach's Christmas Oratorio

Bach’s Christmas Oratorio Bach Collegium Japan Masaaki Suzuki Director Sherezade Panthaki / Soprano Jay Carter / Countertenor Zachary Wilder / Tenor Dominik Wörner / Bass Friday Evening, December 8, 2017 at 8:00 Hill Auditorium Ann Arbor 27th Performance of the 139th Annual Season 139th Annual Choral Union Series Choral Music Series Media partnership provided by WGTE 91.3 FM. Bach Collegium Japan records for BIS. Bach Collegium Japan appears by arrangement with International Arts Foundation, Inc. In consideration of the artists and the audience, please refrain from the use of electronic devices during the performance. The photography, sound recording, or videotaping of this performance is prohibited. PROGRAM Johann Sebastian Bach Christmas Oratorio, BWV 248 (excerpts) Part I Jauchzet, frohlocket, auf, preiset die Tage Part II Und es waren Hirten in derselben Gegend Intermission Part III Herrscher des Himmels, erhöre das Lallen Part VI Herr, wenn die stolzen Feinde schnauben 3 CHRISTMAS ORATORIO, BWV 248 (EXCERPTS) (1734) Johann Sebastian Bach Born March 31, 1685 in Eisenach, Germany Died July 28, 1750 in Leipzig UMS premiere: J.S. Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, nor any of the cantatas which make up the work, has ever been performed as part of a full concert program at UMS. However, arias from the oratorio have shown up on various recital programs over the past century: “Bereite dich, Zion” (Prepare thyself, Zion) on a Marian Anderson recital in Hill Auditorium (1954); “Was will der Hölle Schreken nun” (What will the terrors of Hell now) with the Bach Aria Group featuring soprano Eileen Farrell, tenor Jan Peerce, and cellist Bernard Greenhouse in Hill Auditorium (1960); and “Nur ein Wink von seinen Händen” (Only a wave of His hands) on an Anne Sofie von Otter recital in the Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre (2004). -

Eine Feste Burg

J.S. Bach: Cantata Ein feste Burg, BWV 80: Movements 1, 2, 8 (for component 3: Appraising) Background information and performance circumstances Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Baroque period and has a prolific output of compositions. Many of Bach’s compositions are of a sacred nature and were produced for the churches where he held the position of director of music. In 1723 Bach moved to Leipzig to take up the position of Cantor of St Thomas Church (Thomaskirche), where he remained for the next 27 years. It was here that he composed some of his most renowned works, including the Passions (most notably the St Matthew and St John Passions), the B minor Mass and Christmas Oratorio, in addition to a vast quantity of cantatas. The cantata was an integral part of the Lutheran liturgy and followed immediately after the reading of the Gospel. A cantata is a vocal composition with instrumental accompaniment and comprises many movements. Cantatas were originally written using both sacred and secular texts, but it was in Germany in the Baroque period where they became most associated with the Lutheran Church. Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott (A mighty fortress is our God), BWV 80, is a church cantata by Johann Sebastian Bach. He composed this chorale cantata, in which both text and music are based on a Lutheran hymn, whilst in the position of Cantor of St Thomas Church in Leipzig. It is based on Martin Luther’s hymn of the same name. -

Parodies in J.S. Bach Vocal Works

Page 1 Parodies in Johann-Sebastian Bach vocal works Author: Jean-Pierre Grivois Contents: - Introduction p.2 - Study of the parodies by BWV numbers p.3 - Chronological list of works in which parodies have been found p.31 - Appendix: comparison of texts. Published: January 2019 on Bach Cantatas Website: http://www.bach-cantatas.com/ Page 2 Introduction This document is a tool to work on what is called « parodies » in Johann-Sebastian Bach vocal works (the terms arrangement, revision, actualization would seem to us better adapted). We have been as exhaustive as possible knowing that Bach’s "parodies" could have suffered the same fate as many cantatas and could have been lost. The aim of this document is to be used as a basis of work for musicologists, theologians, linguists, historians … Definition In this document the definition of parody is: the modification of a musical work in order to insert it into a vocal work (cantata, passion, oratorio, mass …). Our definition implies 3 types of parodies: 1- that which consists of modifying the musical writing or the instrumentation or the text of an existing work; 2- that of putting words on an instrumental work originally without words; 3- that which consists in inserting an instrumental work with a new instrumentation into a vocal work. Method We will analyze the parodies by Movement (aria, duet, chorus etc.), except when the music of the original or the parody has been lost: in this case we will just quote it or make a brief comment We choose to present the parodies in their chronological order and not in the chronological order of the original vocal works.