Fantasy on a Theme of Luther Dma Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sources of the Christmas Interpolations in J. S. Bach's Magnificat in E-Flat Major (BWV 243A)*

The Sources of the Christmas Interpolations in J. S. Bach's Magnificat in E-flat Major (BWV 243a)* By Robert M. Cammarota Apart from changes in tonality and instrumentation, the two versions of J. S. Bach's Magnificat differ from each other mainly in the presence offour Christmas interpolations in the earlier E-flat major setting (BWV 243a).' These include newly composed settings of the first strophe of Luther's lied "Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her" (1539); the last four verses of "Freut euch und jubiliert," a celebrated lied whose origin is unknown; "Gloria in excelsis Deo" (Luke 2:14); and the last four verses and Alleluia of "Virga Jesse floruit," attributed to Paul Eber (1570).2 The custom of troping the Magnificat at vespers on major feasts, particu larly Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost, was cultivated in German-speaking lands of central and eastern Europe from the 14th through the 17th centu ries; it continued to be observed in Leipzig during the first quarter of the 18th century. The procedure involved the interpolation of hymns and popu lar songs (lieder) appropriate to the feast into a polyphonic or, later, a con certed setting of the Magnificat. The texts of these interpolations were in Latin, German, or macaronic Latin-German. Although the origin oftroping the Magnificat is unknown, the practice has been traced back to the mid-14th century. The earliest examples of Magnifi cat tropes occur in the Seckauer Cantional of 1345.' These include "Magnifi cat Pater ingenitus a quo sunt omnia" and "Magnificat Stella nova radiat. "4 Both are designated for the Feast of the Nativity.' The tropes to the Magnificat were known by different names during the 16th, 17th, and early 18th centuries. -

Bach Christmas Oratorio Prog Notes

Johann Sebastian Bach Christmas Oratorio Programme Notes Johann Sebastian Bach’s Christmas Oratorio was composed in 1734. The title page of the printed libretto, prepared for the congregation, notes “Oratorio performed over the holy festival of Christmas in the two chief churches in Leipzig.” The oratorio was divided into six parts, each part to be performed at one of the six services held during the Lutheran celebration of the Twelve Nights of Christmas. Parts I, II, IV and VI were each performed twice, at St. Thomas and St. Nicholas in alternate morning and afternoon services. Parts III and V, written for days of lesser significance in the festival, were performed only once at St. Nicholas. The music would have served as the “principal music” for the day, replacing the cantata that would otherwise have been performed. The structure of the Christmas Oratorio is similar to that of Bach’s Passions: Bach presents a dramatic rendering of a biblical text, largely in the form of secco recitative (recitative with simple continuo accompaniment) sung by an Evangelist, and adds to it comments and reflections of both an individual and congregational nature, in the form of arias, choruses, and chorales. The biblical text in question is the story of the birth of Jesus through to the arrival of the three Wise Men, drawn from the Gospels according to Luke and Matthew. The narrative is by its very nature less dramatic than that of the Passions, so Bach introduces a number of arioso passages: accompanied recitatives in which the spectator enters the story. The bass soloist, for example, speaks to the shepherds, and the alto to Herod and to the Wise Men, outside the narrative proper, yet intimately involved with it. -

Baroque and Classical Style in Selected Organ Works of The

BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL STYLE IN SELECTED ORGAN WORKS OF THE BACHSCHULE by DEAN B. McINTYRE, B.A., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairperson of the Committee Accepted Dearri of the Graduate jSchool December, 1998 © Copyright 1998 Dean B. Mclntyre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful for the general guidance and specific suggestions offered by members of my dissertation advisory committee: Dr. Paul Cutter and Dr. Thomas Hughes (Music), Dr. John Stinespring (Art), and Dr. Daniel Nathan (Philosophy). Each offered assistance and insight from his own specific area as well as the general field of Fine Arts. I offer special thanks and appreciation to my committee chairperson Dr. Wayne Hobbs (Music), whose oversight and direction were invaluable. I must also acknowledge those individuals and publishers who have granted permission to include copyrighted musical materials in whole or in part: Concordia Publishing House, Lorenz Corporation, C. F. Peters Corporation, Oliver Ditson/Theodore Presser Company, Oxford University Press, Breitkopf & Hartel, and Dr. David Mulbury of the University of Cincinnati. A final offering of thanks goes to my wife, Karen, and our daughter, Noelle. Their unfailing patience and understanding were equalled by their continual spirit of encouragement. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT ix LIST OF TABLES xi LIST OF FIGURES xii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES xiii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xvi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 11. BAROQUE STYLE 12 Greneral Style Characteristics of the Late Baroque 13 Melody 15 Harmony 15 Rhythm 16 Form 17 Texture 18 Dynamics 19 J. -

The Christology of Bach's St John Passion

PARADOSIS 3 (2016) ‘Zeig uns durch deine Passion’: The Christology of Bach’s St John Passion Andreas Loewe St Paul’s Cathedral Melbourne Melbourne Conservatorium of Music Introduction On a wet, early spring afternoon, on Good Friday 1724, the congregants of Leipzig’s Nikolaikirche witnessed the first performance of Bach’s St John Passion.1 For at least a generation, Good Friday in Leipzig’s principal Lutheran churches—St Thomas’, St Nikolai and the ‘New’ Church—had concluded with the singing of Johann Walter’s chanted Passion.2 As part of the final liturgical observance of the day, the story of the death of Jesus would be sung, combining words and music in order to reflect on the significance of that day. Bach took the proclamation of the cross to a new level – theologically and musically. Rather than use a poetic retelling of the Passion story as his textual basis, Bach made use of a single gospel account, matched with contemporary poems and traditional chorales to retell the trial and death of Jesus. By providing regular opportunities for theological reflection, he purposefully created a “sermon in sound” and so, in his music making, he closely mirrors Lutheran Baroque homiletic principles. An orthodox Lutheran believer throughout his life, Bach’s Passion serves as a vehicle to invite his listeners to make their own his belief that it was “through Christ’s agony and death” that “all the world’s 1 Andreas Elias Büchner, Johann Kanold, Vollständiges und accurates Universal-Register, Aller wichtigen und merckwürdigen Materien (Erfurt: Jungnicol, 1736), 680. 2 As popularised in Gottfried Vopelius, ed., Neu Leipziger Gesangbuch/ Von den schönsten und besten Liedern verfasset/ In welchem Nicht allein des sel. -

May 2 Order of Worship

FIRST BAPTIST CHURCH Historic | Liturgical | Vibrant FIFTH SUNDAY OF EASTERTIDE May 2, 2021 at 11:00 am WE GATHER TO PRAISE GOD Music Notes CHIMING OF THE HOUR Much of the music used in today’s worship service will be excerpts from “Der WELCOME Rev. Katie Callaway & Rev. John Callaway Himmel lacht! Die Erde jubilieret” (Heaven Laughs! Earth Exults) by INVOCATION Johann Sebastian Bach. This work is Bach’s 31st PRELUDE - “Sonata” from Cantata No. 31 by Johann Sebastian Bach church cantata and was North Carolina Baroque Orchestra written for the first day of the Easter season. It was first performed in CALL TO WORSHIP - Psalm 22:25-31 Ellen Davis, Lay Reader Weimar, Germany, on April 21, 1715 and later HYMN - “Christ Is Risen, Shout Hosanna” Tune: HYMN TO JOY reworked for performances in Leipzig. The work is scored for five Christ is risen! Shout hosanna! part choir, large Celebrate this day of days! orchestra, and soprano, tenor, and bass soloists. Christ is risen! Hush in wonder: All creation is amazed. In the desert all surrounding, Guest Musicians See, a spreading tree has grown. Healing leaves of grace abounding Today we welcome the Bring a taste of love unknown. choir of Wake Forest University from Winston Salem, NC. They are Christ is risen! Raise your spirits under the direction of Dr. From the caverns of despair. Christopher Gilliam and Walk with gladness in the morning. accompanied by the North See what love can do and dare. Carolina Baroque Orchestra. The choral Drink the wine of resurrection, program at Wake Not a servant, but a friend. -

The Treatment of the Chorale Wie Scan Leuchtet Der Iorgenstern in Organ Compositions from the Seven Teenth Century to the Twentieth Century

379 THE TREATMENT OF THE CHORALE WIE SCAN LEUCHTET DER IORGENSTERN IN ORGAN COMPOSITIONS FROM THE SEVEN TEENTH CENTURY TO THE TWENTIETH CENTURY THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Paul Winston Renick, B. M. Denton, Texas August, 1961 PREFACE The chorale Wie schn iihtet derMorgenstern was popular from its very outset in 1589. That it has retained its popularity down to the present day is evident by its continually appearing in hymnbooks and being used as a cantus in organ compositions as well as forming the basis for other media of musical composition. The treatment of organ compositions based on this single chorale not only exemplifies the curiously novel attraction that this tune has held for composers, but also supplies a common denominator by which the history of the organ chorale can be generally stated. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE . * . * . * . * * * . * . LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . .0.0..0... 0 .0. .. V Chapter I. THE LUTHERAN CHORALE. .. .. The Development of the Chorale up to Bach The Chorale Wie sch8n leuchtet der Morgenstern II. BEGINNINGS OF THE ORGAN CHORALE . .14 III* ORGAN CHORALS BASED ON WIE SCHN IN THE BAROQUE ERA .. *. .. * . .. 25 Samuel Scheidt Dietrich Buxtehude Johann Christoph Bach Johann Pachelbel Johann Heinrich Buttstet Andreas Armsdorf J. S. Bach IV. ORGAN COMPOSITIONS BASED ON WIE SCHON ...... 42 AFTER BACH . 4 Johann Christian Rinck Max Reger Sigf rid Karg-Elert Heinrich Kaminsky Ernst Pepping Johann Nepomuk David Flor Peeters and Garth Edmund son V. -

B Ach C Antatas G Ardiner

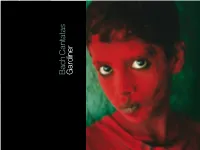

Johann Sebastian Bach 1685-1750 Cantatas Vol 26: Long Melford SDG121 COVER SDG121 CD 1 67:39 For Whit Sunday Erschallet, ihr Lieder, erklinget, ihr Saiten! BWV 172 Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort halten I BWV 59 Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort halten II BWV 74 O ewiges Feuer, o Ursprung der Liebe BWV 34 Lisa Larsson soprano, Nathalie Stutzmann alto Derek Lee Ragin alto, Christoph Genz tenor Panajotis Iconomou bass C CD 2 47:58 For Whit Monday M Erhöhtes Fleisch und Blut BWV 173 Also hat Gott die Welt geliebt BWV 68 Y Ich liebe den Höchsten von ganzem Gemüte BWV 174 K Lisa Larsson soprano, Nathalie Stutzmann alto Christoph Genz tenor, Panajotis Iconomou bass The Monteverdi Choir The English Baroque Soloists John Eliot Gardiner Live recordings from the Bach Cantata Pilgrimage Holy Trinity, Long Melford, 11 & 12 June 2000 Soli Deo Gloria Volume 26 SDG 121 P 2006 Monteverdi Productions Ltd C 2006 Monteverdi Productions Ltd www.solideogloria.co.uk Edition by Reinhold Kubik, Breitkopf & Härtel Manufactured in Italy LC13772 8 43183 01212 1 26 SDG 121 Bach Cantatas Gardiner Bach Cantatas Gardiner CD 1 67:39 For Whit Sunday The Monteverdi Choir The English Flutes 1-7 18:31 Erschallet, ihr Lieder, erklinget, ihr Saiten! BWV 172 Baroque Soloists Marten Root Sopranos Rachel Beckett 8-12 11:38 Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort halten I BWV 59 Suzanne Flowers First Violins 13-20 20:34 Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort halten II BWV 74 Gillian Keith Kati Debretzeni Oboes Emma Preston-Dunlop Penelope Spencer Michael Niesemann 21-25 16:45 -

Bach and the Rationalist Philosophy of Wolff, Leibniz and Spinoza,” 60-71

Chapter 1 On the Musically Theological in Bach’s Cantatas From informal Internet discussion groups to specialized aca demic conferences and publications, an ongoing debate has raged on whether J. S. Bach ought to be considered a purely artistic or also a religious figure.^ A recently formed but now disbanded group of scholars, the Internationale Arbeitsgemeinschaft fiir theologische Bachforschung, made up mostly of German theologians, has made significant contributions toward understanding the religious con texts of Bach’s liturgical music.^ These writers have not entirely captured the attention or respect of the wider world of Bach 1. For the academic side, the most influential has been Friedrich Blume, “Umrisse eines neuen Bach-Bildes,” Musica 16 (1962): 169-176, translated as “Outlines of a New Picture of Bach,” Music and Letters 44 (1963): 214-227. The most impor tant responses include Alfred Durr, “Zum Wandel des Bach-Bildes: Zu Friedrich Blumes Mainzer Vortrag,” Musik und Kirche 32 (1962): 145-152; see also Friedrich Blume, “Antwort von Friedrich Blume,” Musik und Kirche 32 (1962): 153-156; Friedrich Smend, “Was bleibt? Zu Friedrich Blumes Bach-Bild,” DerKirchenmusiker 13 (1962): 178-188; and Gerhard Herz, “Toward a New Image of Bach,” Bach 1, no. 4 (1970): 9-27, and Bach 2, no. 1 (1971): 7-28 (reprinted in Essays on J. S. Bach [Ann Arbor: UMI Reseach Press, 1985], 149-184). 2. For a convenient list of the group’s main publications, see Daniel R. Melamed and Michael Marissen, An Introduction to Bach Studies (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 15. For a full bibliography to 1996, see Renate Steiger, ed., Theologische Bachforschung heute: Dokumentation und Bibliographie der Intemationalen Arbeitsgemeinschaft fiir theologische Bachforschung 1976-1996 (Glienicke and Berlin: Galda and Walch, 1998), 353-445. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION “Works for special occasions” is a broad category that anniversaries in office of Dr. Heinrich Hoeck and Syndi- we have defined for Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach rather cus Johann Klefeker, H 824c and 824d, respectively, were narrowly as a repertoire of specially commissioned, large- intended for public performances, but these lost works are scale works for voices and orchestra. The extant works discussed with the Einführungsmusiken in CPEB:CW, include a birthday cantata, Dank-Hymne der Freundschaft, V/3. The funeral music which Bach provided on occasion H 824e (published in CPEB:CW, V/5.1); a chorus, Spiega, (for example, “Gott, dem ich lebe, des ich bin,” Wq 225) is Ammonia fortunata, Wq 216 (H 829), written for the visit treated in CPEB:CW, V/6, since none of the works sur- of the Swedish Crown Prince in 1770; and a cantata, Musik vive with complete music, rather only single choruses. am Dankfeste wegen des fertigen Michaelisturms, H 823, cel- ebrating the completion of the St. Michaelis tower in 1786. , Wq/H To this could be added the various cantatas that C. P. E. Ich bin vergnügt mit meinem Stande deest Bach wrote while attending the university at Frankfurt an It is regrettable that nearly all of Bach’s early vocal music der Oder: several printed librettos survive, but the music is now lost. There was no trace whatsoever for any vocal for these works is lost (see discussion below). Although we works from the Leipzig years until the fortunate discovery have no record for any choral music before the Magnificat, by Peter Wollny in the fall of 2009 of the autograph com- Wq 215 (first completed in 1749, according to NV 1790), it posing score of an unknown church cantata by the young is our good fortune that a solo cantata written in Leipzig C. -

Christmas Oratorio

Reflections on Bach’s “Christmas Oratorio” by John Harbison Composer John Harbison, whose ties to Boston’s cultural and educational communities are longstanding, celebrates his 80th birthday on December 20, 2018. To mark this birthday, the BSO will perform his Symphony No. 2 on January 10, 11, and 12 at Symphony Hall, and the Boston Symphony Chamber Players perform music of Harbison and J.S. Bach on Sunday afternoon, January 13, at Jordan Hall. The author of a new book entitled “What Do We Make of Bach?–Portraits, Essays, Notes,” Mr. Harbison here offers thoughts on Bach’s “Christmas Oratorio.” Andris Nelsons’ 2018 performances of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio are the Boston Symphony’s first since 1950, when Charles Munch was the orchestra’s music director. Munch may have been the last BSO conductor for whom Bach’s music remained a natural and substantial part of any season. In the 1950s the influence of Historically Informed Practice (HIP) was beginning to be felt. Large orchestras and their conductors began to draw away from 18th-century repertoire, feeling themselves too large, too unschooled in stylistic issues. For Charles Munch, Bach was life-blood. I remember hearing his generous, spacious performance of Cantata 4, his monumental reading of the double-chorus, single-movement Cantata 50. Arriving at Tanglewood as a Fellow in 1958, opening night in the Theatre-Concert Hall, there was Munch’s own transcription for string orchestra of Bach’s complete Art of Fugue! This was a weird and glorious experience, a two-hour journey through Bach’s fugue cycle that seemed a stream of sublime, often very unusual harmony, seldom articulated as to line or sectional contrast. -

Luther, Bach, and the Jews: the Place of Objectionable Texts in the Classroom

religions Article Luther, Bach, and the Jews: The Place of Objectionable Texts in the Classroom Beth McGinnis 1 and Scott McGinnis 2,* 1 Division of Music, School of the Arts, Samford University, 800 Lakeshore Dr., Birmingham, AL 35229, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Religion, Samford University, 800 Lakeshore Dr., Birmingham, AL 35229, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-205-726-4260 Academic Editors: Peter Iver Kaufman and Christopher Metress Received: 16 February 2017; Accepted: 26 March 2017; Published: 1 April 2017 Abstract: This article examines the pedagogical challenges and value of using objectionable texts in the classroom by way of two case studies: Martin Luther’s writings on Jews and two works by J.S. Bach. The use of morally or otherwise offensive materials in the classroom has the potential to degrade the learning environment or even produce harm if not carefully managed. On the other hand, historically informed instructors can use difficult works to model good scholarly methodology and offer useful contexts for investigating of contemporary issues. Moral judgments about historical actors and events are inevitable, the authors argue, so the instructor’s responsibility is to seize the opportunity for constructive dialogue. Keywords: Martin Luther; Johann Sebastian Bach; anti-Judaism; anti-Semitism; pedagogy 1. Introduction Although the Castle Church in Wittenberg famously appears in Martin Luther’s biography as the site of the (possibly mythical but nevertheless) dramatic posting of the Ninety-Five Theses, the “mother church of the Reformation” actually lies a short walk to the east: the Stadtkirche, or City Church, dedicated to St. -

Bach Choir Presents Cantatas by Bach and a Work by Italian Composer Ottorino Respighi for Its Christmas Concerts

Bach Choir presents cantatas by Bach and a work by Italian composer Ottorino Respighi for its Christmas concerts The Bach Choir will perform present Ottorino Respighi's Laud to the Nativity and J.S. Bach's festive Cantata 63 and Cantata 36 at its Christmas concerts Dec. 8 and 9. Contributed Photo: Don Schroder Steve Siegel Special to The Morning Call Sometimes music is most moving when it evokes the past. Familiar works that engage listeners in emotional time-travel include Vaughan Williams’ “Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis” and much of the music of Arvo Part. Ottorino Respighi is another whose music is frequently steeped in the vivid imagery of the Italian Renaissance and Middle Ages. That’s especially true of his "Lauda per la Nativita del Signore” (Laud to the Nativity), his sole sacred choral piece. Respighi’s richly beautiful yet rarely heard work, and J.S. Bach’s festive Cantata 63, “Christen, atzet diesen Tag” (Christians all, this happy day) and Cantata 36, “Schwingt freudig euch empor” Soar joyfully aloft) are the featured works in this year’s Bach Choir of Bethlehem Christmas Concerts. Bach Choir director Greg Funfgeld will lead the Bach Choir and Festival Orchestra in its Christmas concerts on Nov. 8 and 9. The programs are Saturday at the First Presbyterian Church of Allentown, repeated Sunday at the First Presbyterian Church of Bethlehem. The Bach Choir and Bach Festival Orchestra will be led by Bach Choir artistic director Greg Funfgeld and joined by soprano soloists Ellen McAteer and Fiona Gillespie, countertenor Daniel Taylor, tenor Charles Blady and baritone Christopheren Nomura.