Johann Sebastian Bach's St John Passion (BWV 245): A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reform of Baptism and Confirmation in American Lutheranism

LOGIA 1 Review Essay: The Reform of Baptism and Confirmation in American Lutheranism Armand J. Boehme The Reform of Baptism and Confirmation in American Lutheranism. By Jeffrey A. Truscott. Drew University Studies in Liturgy 11. Lanham, Maryland & Oxford: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2003. his book1 is a study of the production of the baptismal the church.” Thus the crafters of LBW greatly expanded T and confirmation rites contained in Lutheran Book of the “assembly’s participation in the baptismal act” (pp. Worship (LBW).2 The theology that underlies LBW 33, 205). These changes flow from a theology of action and its understanding of worship has significantly (liturgy as the work of the people), which emphasizes altered the Lutheran understanding of baptism and the fact that the church or the congregation is the confirmation. The theological foundation of LBW has mediating agent of God’s saving activity (p. 33).6 For influenced other Lutheran church bodies, contributing LBW the sacraments are understood significantly to profound changes in the Lutheran ecclesiologically—as actions of the congregation (pp. landscape. As Truscott wrote, those crafting the 205-206)—rather than soteriologically—as God acting baptismal liturgy in LBW would have to “overturn” old to give his people grace and forgiveness. This leads to an theologies of baptism, deal with “a theology that” emphasis on baby drama, water drama, and other believed in “the necessity of baptism for salvation,” and congregational acts (pp. 24–26, 220). This theology of “would have to convince Lutherans of the need for a new action is tied to an analytic view of justification, that is, liturgical and theological approach to baptism” (p. -

Now Let Us Come Before Him Nun Laßt Uns Gehn Und Treten 8.8

Now Let Us Come Before Him Nun laßt uns gehn und treten 8.8. 8.8. Nun lasst uns Gott, dem Herren Paul Gerhardt, 1653 Nikolaus Selnecker, 1587 4 As mothers watch are keeping 9 To all who bow before Thee Tr. John Kelly, 1867, alt. Arr. Johann Crüger, alt. O’er children who are sleeping, And for Thy grace implore Thee, Their fear and grief assuaging, Oh, grant Thy benediction When angry storms are raging, And patience in affliction. 5 So God His own is shielding 10 With richest blessings crown us, And help to them is yielding. In all our ways, Lord, own us; When need and woe distress them, Give grace, who grace bestowest His loving arms caress them. To all, e’en to the lowest. 6 O Thou who dost not slumber, 11 Be Thou a Helper speedy Remove what would encumber To all the poor and needy, Our work, which prospers never To all forlorn a Father; Unless Thou bless it ever. Thine erring children gather. 7 Our song to Thee ascendeth, 12 Be with the sick and ailing, Whose mercy never endeth; Their Comforter unfailing; Our thanks to Thee we render, Dispelling grief and sadness, Who art our strong Defender. Oh, give them joy and gladness! 8 O God of mercy, hear us; 13 Above all else, Lord, send us Our Father, be Thou near us; Thy Spirit to attend us, Mid crosses and in sadness Within our hearts abiding, Be Thou our Fount of gladness. To heav’n our footsteps guiding. 14 All this Thy hand bestoweth, Thou Life, whence our life floweth. -

An Introduction to the Annotated Bach Scores - Sacred Cantatas Melvin Unger

An Introduction to the Annotated Bach Scores - Sacred Cantatas Melvin Unger Abbreviations NBA = Neue Bach Ausgabe (collected edition of Bach works) BC = Bach Compendium by Hans-Joachim Schulze and Christoph Wolff. 4 vols. (Frankfurt: Peters, 1989). Liturgical Occasion (Other Bach cantatas for that occasion listed in chronological order) *Gospel Reading of the Day (in the Lutheran liturgy, before the cantata; see below) *Epistle of the Day (in the Lutheran liturgy, earlier than the Gospel Reading; see below) FP = First Performance Note: Some of the following material is taken from Melvin Unger’s overview of Bach’s sacred cantatas, prepared for Cambridge University Press’s Bach Encyclopedia. Copyright Melvin Unger. That overview (which is available here with the annotated Bach cantata scores) includes a bibliography. Additional, online sources include the Bach cantatas website at https://www.bach-cantatas.com/ and Julian Mincham’s website at http://www.jsbachcantatas.com/. The German Cantata Before Bach In Germany, Lutheran composers adapted the genre that had originated in Italy as a secular work intended for aristocratic chamber settings. Defined loosely as a work for one or more voices with independent instrumental accompaniment, usually in discrete sections, and employing the ‘theatrical’ style of opera, the Italian cantata it was originally modest in scope—usually comprising no more than a couple of recitative-aria pairs, with an accompaniment of basso continuo. By the 1700s, however, it had begun to include other instruments, and had grown to include multiple, contrasting movements. Italian composers occasionally wrote sacred cantatas, though not for liturgical use. In Germany, however, Lutheran composers adapted the genre for use in the main weekly service, where it subsumed musical elements already present: the concerted motet and the chorale. -

O Ewigkeit, Du Donnerwort Eternity, Thou Thundrous Word BWV 20

Johann Sebastian BACH O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort Eternity, thou thundrous word BWV 20 Kantate zum 1. Sonntag nach Trinitatis für Soli (ATB), Chor (SATB) 3 Oboen, Trompete 2 Violinen, Viola und Basso continuo herausgegeben von Ulrich Leisinger Cantata for the 1st Sunday after Trinity for soli (ATB), choir (SATB) 3 oboes, trumpet 2 violins, viola and basso continuo edited by Ulrich Leisinger English version by Henry S. Drinker Stuttgarter Bach-Ausgaben · Urtext In Zusammenarbeit mit dem Bach-Archiv Leipzig Klavierauszug /Vocal score Paul Horn C Carus 31.020/03 Vorwort Foreword Die Kantate O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort BWV 20 bildet The cantata O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort BWV 20 (Eter nity, den Auftakt für das wohl ehrgeizigste kompositorische Pro- thou thundrous word), marked the beginning of what was jekt, das Johann Sebastian Bach auf sich genommen hat: probably the most ambitious compositional project ever Die Kantate eröffnet den sogenannten Choralkantatenjahr- undertaken by Johann Sebastian Bach: this cantata opens gang, den der Thomaskantor als zweiten Jahrgang von Kir- the annual cycle of so-called chorale cantatas, which the chenkantaten mit dem 1. Sonntag nach Trinitatis 1724 in Thomaskantor began to compose as his second annual Angriff nahm. cycle of church cantatas with a work for the 1st Sunday after Trinity in 1724. Der Kantate liegt das gleichnamige Lied von Johann Rist aus dem Jahre 1642 zugrunde, das in Leipzig durch das This cantata is based on the hymn of the same name by Gesangbuch von Gottfried Vopelius (1682 und öfter) in Johann Rist, published in 1642, which was familiar in einer auf 12 (von ursprünglich 16) Strophen verkürzten Fas- Leipzig through its inclusion in a hymn book assembled by sung bekannt war. -

The Bible in Music

The Bible in Music 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb i 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM The Bible in Music A Dictionary of Songs, Works, and More Siobhán Dowling Long John F. A. Sawyer ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiiiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by Siobhán Dowling Long and John F. A. Sawyer All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dowling Long, Siobhán. The Bible in music : a dictionary of songs, works, and more / Siobhán Dowling Long, John F. A. Sawyer. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8108-8451-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-8452-6 (ebook) 1. Bible in music—Dictionaries. 2. Bible—Songs and music–Dictionaries. I. Sawyer, John F. A. II. Title. ML102.C5L66 2015 781.5'9–dc23 2015012867 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. -

Martin Luther and the Wittenberg Reformation of Worship

Today’s “Worship Wars” in light of Martin Luther and the Wittenberg reformation of worship §1 Some scriptural guidance §1.1 Worship practices The Christian liturgy grows out of the practice of temple and synagogue Luke 4.16-21 Acts 2.42 Acts 13.1-3 Acts 13.14b-16a 1 Corinthians 14.40 Use of hymnody Philippians 2.5b-11 1 Timothy 3.16b 1 Timothy 2.11b.13a Revelation—the Great Te Deum §1.2 Offense/edification General Romans 14 1 Corinthians 8 Specific to the church’s worship 1 Corinthians 14.2-3 §1.3 Unity in the Faith Ephesians 4.1-6 §2 Fast forward: What our confessions teach—and a tension Augsburg Confession, Article 24 Our churches are falsely accused of abolishing the mass. For the mass is retained among us and celebrated with the highest reverence. Practically all the ceremonies that have as a rule been used (usitatae) are preserved, with the exception that here and there German canticles are mixed in with the Latin ones. For, chiefly for this reason is there need of the ceremonies, that they might teach the unlearned. And Paul commands that a language understood by the people be used in the Church. (AC 24.1-4, Lat.)1 It is laid upon our people with injustice that they are supposed to have done away with the mass. For it is well-known that the mass, not to speak boastfully, is held with greater devotion and seriousness among us than among our adversaries….Likewise in the public ceremonies of the mass no notable change has occurred except that in some places 1 “Falso accusantur ecclesiae nostrae, quod missam aboleant. -

Progrmne the DURABILITY Of

PRoGRmnE The DURABILITY of PIANOS and the permanence of their tone quality surpass anything that has ever before been obtained, or is possible under any other conditions. This is due to the Mason & Hamlin system of manufacture, which not only carries substantial and enduring construction to its limit in every detail, but adds a new and vital principle of construc- tion— The Mason & Hamlin Tension Resonator Catalogue Mailed on Jtpplication Old Pianos Taken in Exchange MASON & HAMLIN COMPANY Establishea;i854 Opp. Institute of Technology 492 Boylston Street SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON 6-MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES , ( Ticket Office, 1492 J Telephones_, , Back^ ^ Bay-d \ Administration Offices. 3200 \ TWENTY-NINTH SEASON, 1909-1910 MAX FIEDLER, Conductor prngramm^ of % Nineteenth Rehearsal and Concert WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE FRIDAY AFTERNOON, MARCH 18 AT 2.30 O'CLOCK SATURDAY EVENING, MARCH 19 AT 8.00 O'CLOCK COPYRIGHT, 1909, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A.ELLIS, MANAGER 1417 Mme. TERESA CARRENO On her tour this season will use exclusively j^IANO. THE JOHN CHURCH CO. NEW YORK CINCINNATI CHICAGO REPRESENTED BY 6. L SGHIRMER & CO., 338 Boylston Street, Boston, Mass. Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL |J.M.^w^^w^»l^^^R^^^^^^^wwJ^^w^J^ll^lu^^^^wR^^;^^;^^>^^^>u^^^g,| Perfection in Piano Makinrf THE -^Mamtin Qaartcr Grand Style V, in figured Makogany, price $650 It is tut FIVE FEET LONG and in Tonal Proportions a Masterpiece of piano building^. It IS Cnickering & Sons most recent triumpLi, tke exponent of EIGHTY-SEVEN YEARS experience in artistic piano tuilding, and tlie lieir to all tne qualities tkat tke name of its makers implies. -

Bach Christmas Oratorio Prog Notes

Johann Sebastian Bach Christmas Oratorio Programme Notes Johann Sebastian Bach’s Christmas Oratorio was composed in 1734. The title page of the printed libretto, prepared for the congregation, notes “Oratorio performed over the holy festival of Christmas in the two chief churches in Leipzig.” The oratorio was divided into six parts, each part to be performed at one of the six services held during the Lutheran celebration of the Twelve Nights of Christmas. Parts I, II, IV and VI were each performed twice, at St. Thomas and St. Nicholas in alternate morning and afternoon services. Parts III and V, written for days of lesser significance in the festival, were performed only once at St. Nicholas. The music would have served as the “principal music” for the day, replacing the cantata that would otherwise have been performed. The structure of the Christmas Oratorio is similar to that of Bach’s Passions: Bach presents a dramatic rendering of a biblical text, largely in the form of secco recitative (recitative with simple continuo accompaniment) sung by an Evangelist, and adds to it comments and reflections of both an individual and congregational nature, in the form of arias, choruses, and chorales. The biblical text in question is the story of the birth of Jesus through to the arrival of the three Wise Men, drawn from the Gospels according to Luke and Matthew. The narrative is by its very nature less dramatic than that of the Passions, so Bach introduces a number of arioso passages: accompanied recitatives in which the spectator enters the story. The bass soloist, for example, speaks to the shepherds, and the alto to Herod and to the Wise Men, outside the narrative proper, yet intimately involved with it. -

INHALT DES ZWEITEN BANDES Nr

INHALT DES ZWEITEN BANDES Nr. 121-200 r. ~ ~~ t t Nr, Texte..r~h.n.g .;,ummcnzanl Komponist Advent 121. Gelobet sei Israels Gott . 4 . johann Crüger 122. Hod!gelobet seist du jesu Christe Gom Sohn 2 . Ernst Pepping 123. Vom Olberge zeucht daher ·..... 4 . Joachim a Burck 124. Aus hartem Weh die Menschheit klagt 2-4. Ernst Pepping 125. Gott heilger Schöpfer aller Stern 3 Guillaume Dufay 126. Gelobet sei der König groß . 4 Michael Praetorius 127. Und unser lieben Frauen ... 3 . Ernst Pepping 128. Maria durch ein Dornwald ging 6 Heinrich Kaminski Weibnachren 129. In dulci iubilo ...... 8 Leonhard Schröter 130. Hört zu und seid getrost nun . 4 Leonhard Schröter 131. Christum wir sollen loben schon 4 . Ernst Pepping 132. Christe redemptor omnium . 4 Giov. P. da Palestrina Christe Erlöser aller Welt . 133. Hört zu ihr lieben Leute . 5 Michael Praetorius IH. Universi populi . 4 Michael Praetorius Fröhlich seid all Christenleut 135. In Bethlchem ein Kindelein . 4 Michael Praetorius 136. Ein Kind geborn zu Bethlehem 2~. Michael Practorius Puer natus in Bethlehem . 137. Uns ist ein Kind geboren . 6 . johann Stobäus 138. Aus des Vaters Herz ist gboren 4 . Kurt H essenberg ll9. Zu Bethlehem geboren . 3-4 . Ernst Pcpping Neujahr 140. jesu du zartes Kindelein . 5 Melchior Franck 141. Nun wollen wir das alte Jahr mit Lob und Dank vollenden 5 johann Staden Epiphanias 142. Nun liebe See! nun ist es Zeit . 6 johann Eccard 143. Gott Vater uns sein Sohn fürstellt 3 Adam Gumpelzhaimer Passion 1«. 0 du armer Judas . 6 . Arnold von Bruck 145. Da jesus an dem Kreuze stund . -

Anmerkungen Einleitung

),- 7dc[hakd][d ;_db[_jkd] 1 Erdmann Neumeister hatte in Leipzig Poetik-Vorlesungen gehalten, die er Hu- nold zur Verfügung stellte, da er sie als Pfarrer nicht selbst publizieren wollte. Hunold bringt diese Poetik unter seinem Pseudonym Menantes 1707 erstmals heraus. Menan- tes: Die Allerneueste Art, zur Reinen und Galanten Poesie zu gelangen. Allen Edlen und die- ser Wissenschafft geneigten Gemühtern, zum vollkommenen Unterricht, mit überaus deutlichen Regeln und angenehmen Exempeln ans Licht gestellet. Hamburg 1728/1707. Siehe das ge- samte Kapitel XIX. Von der Opera. S. 394–414, hier S. 412. Zur Würdigung und Analy- se dieser Poetik siehe Viswanathan, Ute-Maria Suessmuth: Die Poetik Erdmann Neu- meisters und ihre Beziehung zur barocken und galanten Dichtungslehre. University of Pittsburgh 1989, S. 86f. Im Folgenden werden die Quellentexte bei der Erstzitation aus- führlich mit bibliographischen Angaben versehen, danach gibt es Kurztitel. 2 Neumeister hat das Libretto von Thomas Corneille zur Oper Bellerophon Paris 1679 übersetzt. Diese Übersetzung haben Hunold und Barthold Feind rezipiert, die beide zwischen 1702 und 1706 in Hamburg in derselben Wohnung lebten. Zu dieser Zeit war Hunold im Besitz von Neumeisters Manuskript. Vgl. Viswanathan, 1989, S. 92f und FN 108, S. 144. Feind arbeitete Bellerophon um zu einer Huldigungsoper an- lässlich der Hochzeit des preußischen Königs Friedrichs I. mit der Mecklenburgischen Prinzessin Sophie Louise. D-Hs 124 in MS 639/3:7. Vgl. Marx, Hans Joachim; Schrö- der, Dorothea: Die Hamburger Gänsemarkt-Oper. Katalog der Textbücher (1678– 1748). Laaber 1995, S. 80. 3 Vgl. Martens, Wolfgang: Die Botschaft der Tugend. Die Aufklärung im Spiegel der deutschen Moralischen Wochenschriften. -

Johann Kuhnau Complete Sacred Works V Opella Musica · Camerata Lipsiensis Gregor Meyer

Johann Kuhnau Complete Sacred Works V Opella Musica · camerata lipsiensis Gregor Meyer cpo 555 260_2 Booklettest.indd 1 04.11.2019 08:46:14 Gregor Meyer (© Jens Gerber) cpo 555 260_2 Booklettest.indd 2 04.11.2019 08:46:14 Johann Kuhnau (1660-1722) Die Geistlichen Werke Vol. 5 Complete Sacred Works Vol. 5 Gott sei mir gnädig nach deiner Güte 11'26 [SATB, 2 Vl, 2 Va, Fg, Bc] 1 Gott, sei mir gnädig nach deiner Güte 2'12 2 Wasche mich wohl von meiner Missetat 1'19 3 Denn ich erkenne meine Missetat 0'22 4 An dir allein hab ich gesündiget 2'08 5 Siehe, ich bin aus sündlichem Samen gezeuget 2'40 6 Lass mich hören Freud und Wonne 2'48 Ich habe Lust abzuscheiden [SATB, Ob, Tr, 2 Vl, Va, Fg, Bc] 15'49 7 Ich habe Lust abzuscheiden 3'25 8 Wie drücket mich des kranken Leibes Bürde! 2'00 9 Es ist genug 0'44 10 Gesetzt, ich bin kein alter Simeon 0'48 11 Es ist genug 1'59 cpo 555 260_2 Booklettest.indd 3 04.11.2019 08:46:15 12 Selig sind die Toten 0'49 13 Wie lieblich klingt ihr Sterbe-Glocken 4'04 14 Mit Fried und Freud ich fahr dahin 2'03 Erschrick, mein Herz, vor dir [SATB, 2 Vl, Va, Fg, Bc] 16'26 15 Sonata 1'01 16 Erschrick, mein Herz, vor dir 1'45 17 Ach, ich bin unrein unrein, krank und matt 3'03 18 Doch g’nug, dass mich die Krankheit nicht in Verzweiflung stürzt 1'43 19 Lieber Meister, hilf mir Armen 2'45 20 Gottlob! 1'16 21 Schnöder Undank 1'31 22 Ich aber kehre mit dem Samariter um 1'32 23 Gott, mein Arzt, mein wahres Leben 1'52 Weicht, ihr Sorgen, aus dem Herzen [S, 2 Vl, Va, Bc] 12'44 24 Weicht, ihr Sorgen, aus dem Herzen 2'43 25 Ich bleib -

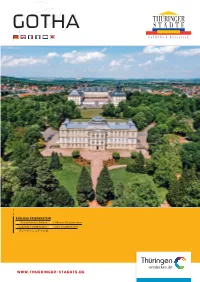

Image Folder Gotha 04 2020

GOTHA GOTHA SCHLOSS FRIEDENSTEIN GB. Friedenstein Palace I F. Château Friedenstein I. Castello Friedenstein I NL. Slot Friedenstein J. フリーデンシュタイン城 WWW.THUERINGER-STAEDTE.DE Entdecken Sie eine der schönsten GB. Discover one of Thuringia’s most beautiful towns I F. Découvrez l’une des villes résidentielles les plus belles de Thuringe I I. Scoprite una delle città più belle della Residenzstädte Thüringens. Turingia, antica residenza ducale I NL. Leer een van de mooiste residentiesteden van Thüringen kennen I J. テューリンゲンの居城都市にようこそ SCHLOSSBERG BUTTERMARKT GB. Schlossberg I F. Schlossberg I I. Schlossberg GB. Buttermarkt I F. Buttermarkt NL. Berg met kasteel I J. シュロスベルク I. Piazza Buttermarkt I NL. Buttermarkt J. ブッターマルクト Schlossgasse „Fallada“ Innungshalle GB. „Fallada“ passage I F. Schlossgasse „Fallada“ GB. Guildhall I F. Salle des commerçants I. Schlossgasse „Fallada“ I NL. Kasteelsteegje I. Sala delle confederazioni artigianali GOTHA „Fallada“ I J. シュロス横丁「ファラーダ」 NL. Gildenhuis I J. イヌングホール In alten Reise beschrei bungen wird In old travel books Gotha is often Dans les anciennes descriptions Gotha viene spesso descritta in an- In oude reisbeschrijvingen wordt 古い旅行案内書を見ると、 Gotha oft als die schönste und described as the richest and most touristiques, Gotha fut souvent tichi diari di viaggio come la città Gotha vaak als de mooiste en rijk- ゴータはテューリンゲン一美 reichste Thü rin ger Stadt dargestellt. Die ehe- attractive city in Thuringia. The former seat of présentée comme la ville la plus belle et la più bella e più ricca della Turingia. ste stad van Thuringen beschreven. し く 豊 か な 町 と 紹 介 さ れ て い ま す 。そ の malige Residenzstadt des Herzogtums Sach- the duchy of Saxe-Gotha is easy to reach and plus riche de la Thuringe.