An Enquiry Into the Abolition of the Inner London Education Authority (1964 to 1988), with Particular Reference to Politics and Policy Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annex 2: Strategic Context for London Borough Exemption Applications

Annex 2: Strategic context for London borough exemption applications Whilst the Mayor of London has made an exemption submission focussing on the locations identified in the London Plan as being of national importance (the Central Activities Zone and its extensions to the east and south-west and the Isle of Dogs), there are other strategically important locations in London which play a role in sustaining future economic growth and employment in outer and inner London, and of cumulative strategic importance to the London and national economy. These locations include: (i) Town Centres identified in the London Plan with potential for office development and other specialist strategic office locations (ii) Strategic Industrial Locations and selected locally significant industrial sites A number of London boroughs are making the case for exemptions with regard to these locations. This note is submitted by the Mayor to support these cases by providing a strategic overview. It sets out the strategic policy context for exemptions submitted by the London boroughs under criteria B of the Government's exemption process, or where appropriate under criteria A where these are of cumulative strategic importance to the London and national economy. Strategic context The London Plan aims to ensure that London continues to excel as a world capital for business, while also supporting the success of local economies and neighbourhoods in all parts of the capital. As Policy 4.1 of the London Plan puts it, the Mayor’s objective is to: “promote and enable the continued -

Bringing Home the Housing Crisis: Domicide and Precarity in Inner London

Bringing Home the Housing Crisis: Domicide and Precarity in Inner London Melanie Nowicki Royal Holloway, University of London PhD Geography, September 2017 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Melanie Nowicki, declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Dated: 24/08/2017 2 Abstract This thesis explores the impact of United Kingdom Coalition/Conservative government housing policies on inner London’s low-income residents. It focuses specifically on the bedroom tax (a social housing reform introduced in 2013) and the criminalisation of squatting in a residential building (introduced in 2012) as case studies. These link to, and contribute towards, three main areas of scholarly and policy interest. First is the changing nature of welfare in the UK, and the relationship between social disadvantage and policy rhetoric in shaping public attitudes towards squatters and social tenants. Second, the thesis initiates better understanding of what impact the policies have made on the homelives of squatters and social tenants, and on housing segregation and affordability more broadly. Third, it highlights the multifaceted ways in which different squatters and social tenants protest and resist the two policies. Methodologically, the thesis is based on in-depth semi-structured interviews with squatters, social tenants affected by the bedroom tax, and multiple stakeholders, including housing association employees, housing solicitors and local councillors. Critical discourse analysis was also employed in order to analyse rhetoric surrounding the two policies. This involved the analysis of political speeches and news articles. Conceptually, the thesis argues for the centrality of critical geographies of home in its analysis and does so through the concepts of domicide, home unmaking, and precarity in order to understand the home as a complex and fluid part of both the lifecourse and wider social politics. -

ALAVES - the Blessley History

Section 7 ALAVES - The Blessley History Editor’s Note - 1 When Ken Blessley agreed to complete the ALAVES story it was decided by the new Local Authority Valuers Association that it would be printed, together with the first instalment, and circulated to members. Both parts have been printed unamended, the only liberty I have taken with the text has been to combine the appendices. As reprinting necessitated retyping any subsequent errors and omissions are my responsibility. Barry Searle, 1987 Editor’s Note - 2 As part of the preparation of “A Century Surveyed”, Ken Blessley’s tour de force has been revisited. The document has been converted into computer text and is reproduced herewith, albeit in a much smaller and condensed typeface in order to reduce the number of pages. Colin Bradford, 2009 may well be inaccuracies. These can, of course, be corrected if they are of any significance. The final version will, it is hoped, be carefully conserved in the records of the Association so that possibly some ALAVES - 1949-1986 future member may be prepared to carry out a similar exercise in perhaps ten years’ time. The circulation of the story is limited, largely because of expense, but also because of the lesser interest of the majority of the current membership in what happened all those years Kenneth Blessley ago. I have therefore, confined the distribution list to the present officers and committee members, past presidents, and others who have held office for a significant period. The story of the Association of Local Authority Valuers 1. HOW IT ALL BEGAN & Estate Surveyors, 1949-1986. -

Inner and Outer London

Autumn 2011 Briefing Inner and outer London: a tale of two cities? Outer London is important to the future success of the wider city; 60% of Londoners live there and 40% Policy implications of the London’s jobs are there. It is the location of • Suburbia may not be fashionable but it is key infrastructure for London and the nation. Outer often successful and adaptable; ‘people like London cannot be considered in isolation from the living there’. centre but the relationship is multifaceted. • A fine grain response is needed that recog - nizes the variety of outer London. There are common issues across outer London; con - gestion, the quality of public transport and other • Some outer London neighbourhoods have public services and the health of local High Streets successfully adapted to significant demo - but there is a danger in focusing on the need for in - graphic change; some feel threatened by their tervention without fully understanding what already proximity to central London, others derive works in the different places. London’s mayoral can - much direct benefit from their closeness. didates cannot afford to ignore outer London but Outer London offers an adaptable, flexible there are no obvious policy prescriptions. • but poorly understood built form. Many people continue to commute from outer to • The economic relationship between outer central London but many more journeys take place and central London is variable. within outer London. These complex patterns of com - muting are hard to satisfy through public transport. • The London Plan should allow for locally dis - Some parts of outer London remain white and tinct solutions; outer London needs nurturing wealthy, other parts are now home to successful eth - not prescription from the Mayor. -

A Description of London's Economy Aaron Girardi and Joel Marsden March 2017

Working Paper 85 A description of London's economy Aaron Girardi and Joel Marsden March 2017 A description of London's economy Working Paper 85 copyright Greater London Authority March 2017 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queens Walk London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk Tel 020 7983 4922 Minicom 020 7983 4000 ISBN 978-1-84781-648-1 Cover photograph © London & Partners For more information about this publication, please contact: GLA Economics Tel 020 7983 4922 Email [email protected] GLA Economics provides expert advice and analysis on London’s economy and the economic issues facing the capital. Data and analysis from GLA Economics form a basis for the policy and investment decisions facing the Mayor of London and the GLA group. GLA Economics uses a wide range of information and data sourced from third party suppliers within its analysis and reports. GLA Economics cannot be held responsible for the accuracy or timeliness of this information and data. The GLA will not be liable for any losses suffered or liabilities incurred by a party as a result of that party relying in any way on the information contained in this report. A description of London's economy Working Paper 85 Contents Executive summary ...................................................................................................................... 2 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 3 2 The structure of London’s local economies ......................................................................... -

Mrs. Thatcher's Return to Victorian Values

proceedings of the British Academy, 78, 9-29 Mrs. Thatcher’s Return to Victorian Values RAPHAEL SAMUEL University of Oxford I ‘VICTORIAN’was still being used as a routine term of opprobrium when, in the run-up to the 1983 election, Mrs. Thatcher annexed ‘Victorian values’ to her Party’s platform and turned them into a talisman for lost stabilities. It is still commonly used today as a byword for the repressive just as (a strange neologism of the 1940s) ‘Dickensian’ is used as a short-hand expression to describe conditions of squalor and want. In Mrs. Thatcher’s lexicon, ‘Victorian’ seems to have been an interchangeable term for the traditional and the old-fashioned, though when the occasion demanded she was not averse to using it in a perjorative sense. Marxism, she liked to say, was a Victorian, (or mid-Victorian) ideo1ogy;l and she criticised ninetenth-century paternalism as propounded by Disraeli as anachronistic.2 Read 12 December 1990. 0 The British Academy 1992. Thanks are due to Jonathan Clark and Christopher Smout for a critical reading of the first draft of this piece; to Fran Bennett of Child Poverty Action for advice on the ‘Scroungermania’ scare of 1975-6; and to the historians taking part in the ‘History Workshop’ symposium on ‘Victorian Values’ in 1983: Gareth Stedman Jones; Michael Ignatieff; Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall. Margaret Thatcher, Address to the Bow Group, 6 May 1978, reprinted in Bow Group, The Right Angle, London, 1979. ‘The Healthy State’, address to a Social Services Conference at Liverpool, 3 December 1976, in Margaret Thatcher, Let Our Children Grow Tall, London, 1977, p. -

A Study in Political Complexity

THE UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD A.LENT LABOUR'S TRANSFORMATION 1983 -1989: A STUDY IN POLITICAL COMPLEXITY THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE Of PhD. 1997 (/ (., "", './1",' . ";~j'- i LABOUR'S TRANSFORMATION 1983 -1989: A STUDY IN POLITICAL COMPLEXITY ADAM LENT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR TilE DEGREE OF PhD. DEPARTl\IENT OF POLITICS SHEFFIELD UNIVERSITY AUGUST 1997 ii CONTENTS Acknowledgements III Abstract v A Note on References VII 1. Introduction 1 PART I: COMPLEXITY AND POLITICS 2. Towards Complexity in Political Analysis 14 3. Complexity and Analysis of Labour in the 1980s 77 PART n: LABOUR'S TRANSFORMATION 1983-1989 4. The Early Days of the Leadership 126 5. The Miners, Militant and the Rates 184 6. Organisational Change 232 7. The New Agenda 270 8. Election Defeat and Leadership Challenge 311 9. Policy Reform and the New Establishment 354 10. Conclusion: Acknowledging Simplification 400 References. 424 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank: the following for their help, support and advice regarding this thesis: Tim Bale, Iulian Bass, David Blunkett, Roger Charlton, Andrew Chipperfield, David Donald, Daniel Fox, Andrew Gamble, Stephen George, Alan Haworth, Bill Hughes, Tim Jordan, Mike Kenny, Sheena MacKenzie, Hugh McLachlan, Patrick Seyd, Eric Shaw, Martin Smith, Gary Taylor and to all those who attended and contributed to seminars at which I presented papers based on this thesis. The libraries used in this research were as follows: Sheffield University Library; Sheffield Hallam University Library; Sheffield City Library; the library at The Museum of Labour History; Glasgow Caledonian University Library; the British Library of Political and Economic Science; and the newspapers and periodicals branch of the British Library. -

The Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001 the Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001

8 Philip Lynch The Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001 The Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001 Philip Lynch As Conservatives reflected on the 1997 general election, they could agree that the issue of Britain’s relationship with the European Union (EU) was a significant factor in their defeat. But they disagreed over how and why ‘Europe’ had contributed to the party’s demise. Euro-sceptics blamed John Major’s European policy. For Euro-sceptics, Major had accepted develop- ments in the European Union that ran counter to the Thatcherite defence of the nation state and promotion of the free market by signing the Maastricht Treaty. This opened a schism in the Conservative Party that Major exacer- bated by paying insufficient attention to the growth of Euro-sceptic sentiment. Membership of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) prolonged recession and undermined the party’s reputation for economic competence. Finally, Euro-sceptics argued that Major’s unwillingness to rule out British entry into the single currency for at least the next Parliament left the party unable to capitalise on the Euro-scepticism that prevailed in the electorate. Pro-Europeans and Major loyalists saw things differently. They believed that Major had acted in the national interest at Maastricht by signing a Treaty that allowed Britain to influence the development of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) without being bound to join it. Pro-Europeans noted that Thatcher had agreed to an equivalent, if not greater, loss of sovereignty by signing the Single European Act. They believed that much of the party could and should have united around Major’s ‘wait and see’ policy on EMU entry. -

Paedophilia – the Radical Case

Contents Note on using this e-book edition Preface New preface (1998) by Tom O'Carroll [NOTE: Missing from original .HTML files , so not included here] Chapter 1 The Seeds of Rebellion Chapter 2 Children's Sexuality: What Do We Mean? Chapter 3 The 'Molester' and His 'Victim' Chapter 4 Paedophilia in Action Chapter 5 Do Children NEED Sex? Chapter 6 Towards More Sensible Laws Chapter 7 The Philosophy of Children's Rights Chapter 8 'Consent' and 'Willingness' Chapter 9 Power and Equality Chapter 10 Children in Erotica and Pornography Chapter 11 The Beginnings of Radical Paedophilia in Britain Chapter 12 The Big Bang Chapter 13 A Wider Perspective Bibliography 1998: Further reading Websites of Interest Credits 1998 HTML edition 2013 .PDF e-book edition Note about using this special e-book edition Just think – if this book were e-mailed to all the politicians, lawmakers and journalists around the country (or even the world!) it would make a difference. Do you want to make a difference? Then you be the one to do it now! Paedophilia – The Radical Case by Tom O'Carroll by the Editor of this 2013 special .PDF e-book edition. For the reader's convenience, the table of contents contains “hyper-links” (links you can click) to each Chapter. Other hyper-links aid in navigation throughout the book. Each reference/footnote – indicated by a raised number in the text (i.e. 21) – now includes a hyper-link to the corresponding note. At the end of each reference/footnote is a ^ symbol, which upon “clicking”, will return the reader to the main text. -

Holders of Ministerial Office in the Conservative Governments 1979-1997

Holders of Ministerial Office in the Conservative Governments 1979-1997 Parliamentary Information List Standard Note: SN/PC/04657 Last updated: 11 March 2008 Author: Department of Information Services All efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy of this data. Nevertheless the complexity of Ministerial appointments, changes in the machinery of government and the very large number of Ministerial changes between 1979 and 1997 mean that there may be some omissions from this list. Where an individual was a Minister at the time of the May 1997 general election the end of his/her term of office has been given as 2 May. Finally, where possible the exact dates of service have been given although when this information was unavailable only the month is given. The Parliamentary Information List series covers various topics relating to Parliament; they include Bills, Committees, Constitution, Debates, Divisions, The House of Commons, Parliament and procedure. Also available: Research papers – impartial briefings on major bills and other topics of public and parliamentary concern, available as printed documents and on the Intranet and Internet. Standard notes – a selection of less formal briefings, often produced in response to frequently asked questions, are accessible via the Internet. Guides to Parliament – The House of Commons Information Office answers enquiries on the work, history and membership of the House of Commons. It also produces a range of publications about the House which are available for free in hard copy on request Education web site – a web site for children and schools with information and activities about Parliament. Any comments or corrections to the lists would be gratefully received and should be sent to: Parliamentary Information Lists Editor, Parliament & Constitution Centre, House of Commons, London SW1A OAA. -

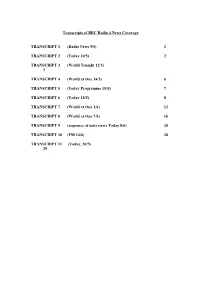

Transcripts of BBC Radio 4 News Coverage TRANSCRIPT 1

Transcripts of BBC Radio 4 News Coverage TRANSCRIPT 1 (Radio News 9/5) 2 TRANSCRIPT 2 (Today 10/5) 2 TRANSCRIPT 3 (World Tonight 12/5) 3 TRANSCRIPT 4 (World at One 14/5) 6 TRANSCRIPT 5 (Today Programme 15/5) 7 TRANSCRIPT 6 (Today 18/5) 8 TRANSCRIPT 7 (World at One 1/6) 12 TRANSCRIPT 8 (World at One 7/6) 16 TRANSCRIPT 9 (sequence of interviews Today 8/6) 20 TRANSCRIPT 10 (PM 14/6) 28 TRANSCRIPT 11 (Today, 20/5) 29 RADIO TRANSCRIPT 1 (Radio News 9/5) James Cox: William Hague has dismissed the breakaway Pro-Europe Conservatives as fanatics after a claim that next month’s European elections will finish him off as the Tory leader. The leader of the rebel group John Stevens said that despite Tory successes in the local council elections, the party’s split over Europe would see its share of the vote fall to around 25% in next month’s poll. But Mr Hague, interviewed by David Frost, thoroughly rejected the claims. Nicholas Jones reports. Nicholas Jones: The Conservatives knew that they could hardly fail to make significant gains in last week’s council elections. But because of the party’s continuing feud over Europe, the Tories’ chances of a continued recovery in next month’s European elections are clouded in uncertainty. The pro-European Conservatives’ leader, John Stevens, said William Hague was mad to have ruled out British membership of the Euro as far ahead as the next Parliament. He predicted that the Tory vote would drop to 25% and that it would be the end of Mr Hague. -

Text Cut Off in the Original 232 6

IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk TEXT CUT OFF IN THE ORIGINAL 232 6 ORGANISATIONAL CHANGE Between 1983 and 1989 there were a series of important changes to Party organisation. Some of these were deliberately pursued, some were more unexpected. All were critical causes, effects and aspects of the transformation. Changes occurred in PLP whipping, Party finance, membership administration, disciplinary procedures, candidate selection, the policy-making process and, most famously, campaign organisation. This chapter makes a number of assertions about this process of organisational change which are original and are inspired by and enhance the search for complexity. It is argued that the organisational aspect of the transformation of the 1980s resulted from multiple causes and the inter-retroaction of those causes rather than from one over-riding cause. In particular, the existing literature has identified organisational reform as originating with a conscious pursuit by the core leadership of greater control over the Party (Heffernan ~\ . !.. ~ and Marqusee 1992: passim~ Shaw 1994: 108). This chapter asserts that while such conscious .... ~.. ,', .. :~. pursuit was one cause, other factors such as ad hoc responses to events .. ,t~~" ~owth of a presidential approach, the use of powers already in existence and the decline of oppositional forces acted as other causes. This emphasis upon multiple causes of change is clearly in keeping with the search for complexity. 233 This chapter also represents the first detailed outline and analysis of centralisation as it related not just to organisational matters but also to the issue of policy-making. In the same vein the chapter is particularly significant because it relates the centralisation of policy-making to policy reform as it occurred between 1983 and 1987 not just in relation to the Policy Review as is the approach of previous analyses.