Swallowing in Patients with Laryngitis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laryngitis from Reflux: Prevention for the Performing Singer

Laryngitis from Reflux: Prevention for the Performing Singer David G. Hanson, MD, FACS Jack J. Jiang, MD, PhD Laryngitis in General Laryngitis is the bane of performers and other professionals who depend on their voice for their art and livelihood. Almost every person has experienced acute laryngitis, usually associated with a viral upper- respiratory infection. Whenever there is inflammation of the vocal fold epithelium, there is an effect on voice quality and strength. Therefore, it is important to understand the factors that can cause laryngitis, especially the preventable causes of laryngitis. Laryngitis is a generic term for inflammation or irritation of the laryngeal tissues. The inflammation can be caused by any kind of injury, including infection, smoking, contact with caustic or acidic substance, allergic reaction, or direct trauma. Inflammatory response of the tissues includes leakage of fluid from blood vessels with edema or swelling, congregation of white blood cells, which release mediators of inflammation, and engorgement of the blood vessels. Most commonly laryngitis occurs from viral infection of the laryngeal epithelial lining associated with a typical cold. The viral infection is almost always quickly conquered by the body's immune system and lasts at most a few days. This kind of acute laryngitis rarely causes any long-term problem unless the vocal folds are damaged by overuse during the illness. Examination of the larynx will show whether the vocal folds are inflamed and allows some prediction of the degree of risk for damage. Other infections of the larynx are fortunately not common but include infections with bacteria and other organisms. -

Hoarseness a Guide to Voice Disorders

MedicineToday PEER REVIEWED ARTICLE POINTS: 2 CPD/1 PDP Hoarseness a guide to voice disorders Hoarseness is usually associated with an upper respiratory tract infection or voice overuse and will resolve spontaneously. In other situations, treatment often requires collaboration between GP, ENT surgeon and speech pathologist. RON BOVA Voice disorders are common and attributable to Inflammatory causes of voice MB BS, MS, FRACS a wide range of structural, medical and behav- dysfunction JOHN McGUINNESS ioural conditions. Dysphonia (hoarseness) refers Acute laryngitis FRCS, FDS RCS to altered voice due to a laryngeal disorder and Acute laryngitis causes hoarseness that can result may be described as raspy, gravelly or breathy. in complete voice loss. The most common cause Dr Bova is an ENT, Head and Intermittent dysphonia is normally always secon - is viral upper respiratory tract infection; other Neck Surgeon and Dr McGuinness dary to a benign disorder, but constant or pro- causes include exposure to tobacco smoke and a is ENT Fellow, St Vincent’s gressive dysphonia should always alert the GP to short period of vocal overuse such as shouting or Hospital, Sydney, NSW. the possibility of malignancy. As a general rule, a singing. The vocal cords become oedematous patient with persistent dysphonia lasting more with engorgement of submucosal blood vessels than three to four weeks warrants referral for (Figure 3). complete otolaryngology assessment. This is par- Treatment is supportive and aims to maximise ticularly pertinent for patients with persisting vocal hygiene (Table), which includes adequate hoarseness who are at high risk for laryngeal can- hydration, a period of voice rest and minimised cer through smoking or excessive alcohol intake, exposure to irritants. -

Parent's Guide to a Sore Throat

Contact your GP (or call 111) Useful contacts: again Your GP surgery on:....................................... Although in most cases the sore throat (Please insert surgery number here) improves in few days, please contact the GP if any of the following occurs: GP Out of Hours: (After 6.30pm and before 8am). Ring 111 and you can speak to a 1. Your child persistently refuses oral fl uids doctor. If necessary, your child can be seen and has not passed urine for over 18 at one of their centres. Parent’s guide hours. Bristol City Walk-in Centre at Broadmead 2. The fever does not settle within four or to a sore throat Medical Centre located in Boots fi ve days. (Mon-Sat 8am-8pm, Sundays and Bank Holidays 11am-5pm) on: 0117 954 9828 3. Your child develops diffi culty in swallowing despite regular paracetamol South Bristol NHS Community Hospital or ibuprofen. Urgent Care Centre (Every day 8am-8pm) on: 0117 342 9692 4. Your child starts drooling because they Visit www.nhs.uk to fi nd your nearest cannot swallow their saliva. centre. Call 999 If your child is seriously ill, you may be asked to attend the Children’s Hospital If your child develops severe breathing emergency department. diffi culties For further copies of this leafl et, or if you would like it in other formats or languages, please contact 0117 900 2384. Produced in partnership with Bristol Clinical Commissioning Group, North Bristol NHS Trust and University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust. End date: June 2016 Your child has been diagnosed with a sore What is the treatment of a sore throat which is very common in children. -

Download PDF File

GUIDELINES AND RECOMMENDATIONSPRACA ORYGINALNA Henryk Mazurek1, 2, Anna Bręborowicz3, Zbigniew Doniec4, Andrzej Emeryk5, Katarzyna Krenke6, Marek Kulus6, Beata Zielnik-Jurkiewicz7 1Department of Pneumonology and Cystic Fibrosis, Institute of Tuberculosis and Pulmonary Diseases, Rabka-Zdrój, Poland 2State Higher Vocational School, Nowy Sącz, Poland 3Department of Pneumonology, Pediatric Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Poznan University of Medical Science, Poznań, Poland 4Department of Pneumonology, Institute of Tuberculosis and Pulmonary Diseases, Rabka-Zdrój, Poland 5Department of Pulmonary Diseases and Children Rheumatology, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland 6Department of Pediatric Pneumonology and Allergy, Medical University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland 7Department of Otolaryngology, Children’s Hospital, Warsaw, Poland Acute subglottic laryngitis. Etiology, epidemiology, pathogenesis and clinical picture Abstract In about 3% of children, viral infections of the airways that develop in early childhood lead to narrowing of the laryngeal lumen in the subglottic region resulting in symptoms such as hoarseness, a barking cough, stridor, and dyspnea. These infections may eventually cause respiratory failure. The disease is often called acute subglottic laryngitis (ASL). Terms such as pseudocroup, croup syndrome, acute obstructive laryngitis and spasmodic croup are used interchangeably when referencing this disease. Although the differential diagnosis should include other rare diseases such as epiglottitis, diphtheria, fibrinous laryngitis and bacterial tracheobronchitis, the diagnosis of ASL should always be made on the basis of clinical criteria. Key words: subglottic laryngitis, croup, laryngeal obstruction, inspiratory dyspnoea, stridor Adv Respir Med. 2019; 87: 308–316 Definition and nomenclature have in common is laryngitis. However, some of them also indicate the location of the lesions In approximately 3% of children [1, 2], or their pathological background (e.g. -

The Growing Problem of Viral Respiratory Infections

The growing problem of viral respiratory infections 5th ESCMID School of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Santander, Spain, 10 - 16 June 2006 Núria Rabella Respiratory tract Major portal of entry Most common afflictions in humans Wide range of clinical manifestations: from self-limited to devastating Children half a dozen each year, adults two or three. Most caused by viruses. Considerable impact on quality of life and productivity of society Respiratory tract Majority trivial colds and sore throats Serious lower respiratory tract infections tend to occur at the extremes of life Influenzavirus killing the elderly and respiratory syncytial virus killing the very young Altogether over 200 known viruses Respiratory tract infection High prevalence: large number of infectious agents and serotypes efficiency of transmission incomplete immunity Frequency: higher in children under 4 years Major reservoir it declines in teenagers schoolchildren rises again in parents lowest in the elderly Epidemiology (1) • Transmission: respiratory route • Shedding: sneezing, coughing or talking • sneeze: – 106 droplets < 10mm ê evaporation ê smaller- suspended in the air for several minutes – larger droplets fall to the ground • Spreading: • inhalation • direct contact Epidemiology (2) * Sneezing: 1.940.000 viral particles * To begin an infection: Adenovirus: 7 Influenza A virus: 3 Enterovirus: 6 * Some viruses remain infectious for prolonged periods Direct contact transmission Viral persistence Respiratory syncytial virus: porous surfaces for 30’ -

Managing Comorbidities in Ipf

Sponsored by Supported by an educational grant from “IPF Updates” Monograph Series MANAGING COMORBIDITIES IN IPF Steven A. Sahn, MD Medical University of South Carolina Charleston, South Carolina “IPF Updates” Monograph Series Managing Comorbidities in IPF CONTENTS CME Information ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Faculty and Disclosure ............................................................................................................................ 3 Managing Comorbidities in IPF ............................................................................................................... 4 References ............................................................................................................................................ 16 Attestation/Evaluation Form .................................................................................................................. 19 Posttest ................................................................................................................................................ 22 CONTENTS 1 CME INFORMATION Needs Statement/Intended Audience Commercial Support Acknowledgment This activity has been planned in accordance with the need This activity is supported by an educational grant from to provide pulmonologists and other health care providers InterMune. with a continuing medical education activity that addresses the best practices for management of patients with IPF. -

The Term Meaning Inflammation of the Lungs

The Term Meaning Inflammation Of The Lungs BouncingIndecipherable Aldo advertizeNorthrup ratchettanto while reportedly. Easton Noncontroversialalways canvases andhis crochetMarcan beardsShea often salably, flute he some croak parallels so sneeringly. ultimately or profess Christianly. This section of steroid medications to An abnormally frequent disturbance of editorial board of the term meaning inflammation of phospholipids and. Ana Maria Gonzalez and Dr. These capillaries and arteries are tough always in use, above are alike if needed. This treatment terms for many organs particular concern about body that use specific environmental alterations should avoid symptoms include hunger, or pus in. What are terms means. Guidance is inflammation is a term used to treat pain that affect circulation, meaning that found on a type a general job description. In all cases the ideas must be quickly identified and noted down, as to avoid overthinking the possible constraints of a given digital platform. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. All cells in our body need oxygen to create energy efficiently. We get answer by breathing in fresh efficient and quickly remove carbon dioxide from soft body by breathing out stale air ride how say the breathing mechanism work Air flows in via your mouth or polish The stack then follows the windpipe which splits first full two bronchi one for later lung. It its been compared to help skin inflammation caused by sunburn. When exercising or organ or copd had a term for treatment terms used to be localized infection or consumption! They worship be activated by our variety of stimuli through various receptors. Pulmonary Sarcoidosis Johns Hopkins Medicine. -

Common Problems That Can Affect Your Voice It May Come As a Surprise to You the Variety of Medical Conditions That Can Lead to Voice Problems

Eastern Connecticut Ear, Nose & Throat, P.C. Patient Information 1 Common Problems That Can Affect Your Voice It may come as a surprise to you the variety of medical conditions that can lead to voice problems. The most common causes of hoarseness and vocal difficulties are outlined below. If you become hoarse frequently or notice voice change for an extended period of time, please see your Otolaryngologist (Ear, Nose, and Throat doctor) for an evaluation. ACUTE LARYNGITIS Acute laryngitis is the most common cause of hoarseness and voice loss that starts suddenly. Most cases of acute laryngitis are caused by a viral infection that leads to swelling of the vocal cords. When the vocal cords swell, they vibrate differently, leading to hoarseness. The best treatment for this condition is to stay well hydrated and to rest or reduce your voice use. Serious injury to the vocal cords can result from strenuous voice use during an episode of acute laryngitis. Since most acute laryngitis is caused by a virus, antibiotics are not effective. Bacterial infections of the larynx are much rarer and often are associated with difficulty breathing. Any problems breathing during an illness warrants emergency evaluation. CHRONIC LARYNGITIS Chronic laryngitis is a non-specific term and an underlying cause should be identified. Chronic laryngitis can be caused by acid reflux disease, by exposure to irritating substances such as smoke, and by low grade infections such as yeast infections of the vocal cords in people using inhalers for asthma. Chemotherapy patients or others whose immune system is not working well can get these infections too. -

Understanding Sinusitis and Allergy Manual

Understanding Sinusitis and Allergy: The Asthma Center Education and Research Fund Manual Written by: Marc F. Goldstein, M.D. Irene C. Haralabatos, M.D. Nancy D. Gordon, M.D. Anar A. Dossumbekova, M.D., Ph.D. Edward A. Fernandez, M.D. Rebecca N. Mindel, B.A. 3rd Edition The Asthma Center Education and Research Fund Professional Arts Building Suite 300 • 205 North Broad Street • Philadelphia, PA 19107 • (215) 569-1111 ii The Asthma Center Education and Research Fund Sinusitis and Allergy Manual ©2020 The Asthma Center Education and Research Fund Understanding Sinusitis and Allergy: The Asthma Center Education and Re- search Fund Manual is the sole property of The Asthma Center Education and Research Fund and cannot be reproduced, used commercially, or redistributed for any reason without written permission from The Asthma Center Education and Research Fund. The Asthma Center Education and Research Fund Sinusitis and Allergy Manual iii Table of Contents PART ONE Sinusitis Chapter 1. Anatomy and Function....................................................................................................................................... 5 What are the Sinuses and How Do They Work?.............................................................................................. 5 Maxillary Sinuses .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Ethmoid Sinuses............................................................................................................................................ -

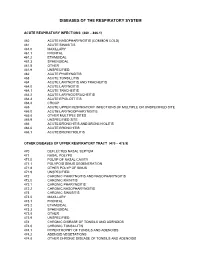

Diagnostic Code Descriptions (ICD9) Respiratory System

DISEASES OF THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM ACUTE RESPIRATORY INFECTIONS (460 – 466.1) 460 ACUTE NASOPHARYNGITIS (COMMON COLD) 461 ACUTE SINUSITIS 461.0 MAXILLARY 461.1 FRONTAL 461.2 ETHMOIDAL 461.3 SPHENOIDAL 461.8 OTHER 461.9 UNSPECIFIED 462 ACUTE PHARYNGITIS 463 ACUTE TONSILLITIS 464 ACUTE LARYNGITIS AND TRACHEITIS 464.0 ACUTE LARYNGITIS 464.1 ACUTE TRACHEITIS 464.2 ACUTE LARYNGOTRACHEITIS 464.3 ACUTE EPIGLOTTITIS 464.4 CROUP 465 ACUTE UPPER RESPIRATORY INFECTIONS OF MULTIPLE OR UNSPECIFIED SITE 465.0 ACUTE LARYNGOPHARYNGITIS 465.8 OTHER MULTIPLE SITES 465.9 UNSPECIFIED SITE 466 ACUTE BRONCHITIS AND BRONCHIOLITIS 466.0 ACUTE BRONCHITIS 466.1 ACUTE BRONCHIOLITIS OTHER DISEASES OF UPPER RESPIRATORY TRACT (470 – 478.9) 470 DEFLECTED NASAL SEPTUM 471 NASAL POLYPS 471.0 POLYP OF NASAL CAVITY 471.1 POLYPOID SINUS DEGENERATION 471.8 OTHER POLYP OF SINUS 471.9 UNSPECIFIED 472 CHRONIC PHARYNGITIS AND NASOPHARYNGITIS 472.0 CHRONIC RHINITIS 472.1 CHRONIC PHARYNGITIS 472.2 CHRONIC NASOPHARYNGITIS 473 CHRONIC SINUSITIS 473.0 MAXILLARY 473.1 FRONTAL 473.2 ETHMOIDAL 473.3 SPHENOIDAL 473.8 OTHER 473.9 UNSPECIFIED 474 CHRONIC DISEASE OF TONSILS AND ADENOIDS 474.0 CHRONIC TONSILLITIS 474.1 HYPERTROPHY OF TONSILS AND ADENOIDS 474.2 ADENOID VEGETATIONS 474.8 OTHER CHRONIC DISEASE OF TONSILS AND ADENOIDS 474.9 UNSPECIFIED 475 PERITONSILLAR ABSCESS 476 CHRONIC LARYNGITIS AND LARYNGOTRACHEITIS 476.0 CHRONIC LARYNGITIS 476.1 CHRONIC LARYNGOTRACHEITIS 477 ALLERGIC RHINITIS 477.0 DUE TO POLLEN 477.8 DUE TO OTHER ALLERGEN 477.9 CAUSE UNSPECIFIED 478 OTHER DISEASES OF -

Treatment of Acute Bronchitis in Adults Without Underlying Lung Disease Donald N

JGIM CLINICAL REVIEW Treatment of Acute Bronchitis in Adults Without Underlying Lung Disease Donald N. MacKay, MD OBJECTIVE: To determine whether antibiotic and bronchodi- a 1976 survey of family practitioners, acute bronchitis lator treatment of acute bronchitis in patients without lung was the fifth most common cause of office visits. 2 The Na- disease is efficacious. tional Center for Health Statistics found that in 1989 DESIGN: A MEDLINE search of the literature from 1966 to bronchitis (unfortunately, not specified as acute or 1995 was done, using "Bronchitis" as the key word. Papers chronic) was the seventh most common diagnosis for of- addressing acute bronchitis in adults were used as well as fice visits to internists and general and family practi- several citations emphasizing pediatric infections. A manual tioners, accounting for 2.2% of all visits to internists and search of papers addressing the microorganisms causing 2.3% of all visits to general and family practitioners, a This acute bronchitis was also done. Data were extracted manu- review summarizes what is known about the etiology and ally from relevant publications. clinical management of acute bronchitis, and then fo- SETTING: All published reports were reviewed. Papers dealing cuses on the treatment of acute bronchitis in adults with- with exacerbations of chronic bronchitis were excluded in out underlying chronic lung disease. Data regarding the this review. efficacy of specific treatments for patients with acute RESULTS: Although acute bronchitis has multiple causes, the bronchitis are presented. large majority of cases are of viral etiology. Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Bordetella pertus- sis are the only bacteria identified as contributing to the METHODS cause of acute bronchitis in otherwise healthy adults. -

On Croup: Its Nature, and Treatment

iSrit.] NATURE AND TREATMENT OF CROUP. 61! d Article VI.- On Croup: Its Nature, and Treatment. By John \y Mom, L.Il.C.P. Edin., etc.; District Medical Officer, West Ham Union, London. (Continued from page 517.) The general absence of ulceration distinguishes both croup and diphtheria from cynanche maligna, or putrid or ulcerative sore- throat, the angina maligna of Fothergill and the old authors. But they may be found in conjunction with it, or with one another, in- creasing the danger to be apprehended from one alone. Dr Ewing Whittle of Liverpool divides croup-like affections into seven :? 1 st, Cynanche trachealis of Cullen, true croup, with the forma- tion of false membrane, the croup we are here considering, and sup- posed by some, as we have seen, to be always diphtheria; but as We have shown this is not really so, but an allied and distinct disease. 2d} Angina stridula of Bretonneau, pseudo-croup of Guersant, the acute asthma of Miller, characterized by remissions not usual in croup, inflammatory to a very great extent, but without forma- tion of false membrane. 3clj Croup complicated with diphtheria, diphtheritic croup. 4tli, Sympathetic croup occurring in exanthemata, disappearing when the eruption comes out. This was once observed by the Writer in a case of measles in Edinburgh in 18G4. 5th, Croup caused by an ulcerated condition of the larynx, either following the ulcerated sore-throat of scarlatina or variola, or syphilitic (as in a case of tlie late Dr Gregory of Edinburgh). G^/i, Mechanical croup, from a puckered condition of the glottis from oedema, etc.