Hoarseness a Guide to Voice Disorders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communicable Diseases of Children

15 Communicable Diseases of Children Dennis 1. Baumgardner The communicable diseases of childhood are a source of signif from these criteria, the history, physical examination, and ap icant disruption for the family and a particular challenge to the propriate laboratory studies often define one of several other family physician. Although most of these illnesses are self more specific respiratory syndromes as summarized in limited and without significant sequelae, the socioeconomic Table 15.1.3-10 impact due to time lost from school (and work), costs of medi Key points to recall are that significant pharyngitis is not cal visits and remedies, and parental anxiety are enormous. present with most colds, that most colds are 3- to 7-day Distressed parents must be treated with sensitivity, patience, illnesses (except for lingering cough and coryza for up to and respect for their judgment, as they have often agonized for 2 weeks), and that abrupt worsening of symptoms or develop hours prior to calling the physician. They are usually greatly ment of high fever mandates prompt reevaluation. Tonsillo reassured when given a specific diagnosis and an explanation of pharyngitis (hemolytic streptococci, Epstein-Barr virus, the natural history of even the most minor syndrome. adenovirus, Corynebacterium) usually involves a sore throat, It is essential to promptly differentiate serious from benign fever, erythema of the tonsils and pharynx with swelling or disorders (e.g., acute epiglottitis versus spasmodic croup), to edema, and often headache and cervical adenitis. In addition to recognize serious complications of common illnesses (e.g., var the entities listed in Table 15.1, colds must also be differenti icella encephalitis), and to recognize febrile viral syndromes ated from allergic rhinitis, asthma, nasal or respiratory tree (e.g., herpangina), thereby avoiding antibiotic misuse. -

Laryngitis from Reflux: Prevention for the Performing Singer

Laryngitis from Reflux: Prevention for the Performing Singer David G. Hanson, MD, FACS Jack J. Jiang, MD, PhD Laryngitis in General Laryngitis is the bane of performers and other professionals who depend on their voice for their art and livelihood. Almost every person has experienced acute laryngitis, usually associated with a viral upper- respiratory infection. Whenever there is inflammation of the vocal fold epithelium, there is an effect on voice quality and strength. Therefore, it is important to understand the factors that can cause laryngitis, especially the preventable causes of laryngitis. Laryngitis is a generic term for inflammation or irritation of the laryngeal tissues. The inflammation can be caused by any kind of injury, including infection, smoking, contact with caustic or acidic substance, allergic reaction, or direct trauma. Inflammatory response of the tissues includes leakage of fluid from blood vessels with edema or swelling, congregation of white blood cells, which release mediators of inflammation, and engorgement of the blood vessels. Most commonly laryngitis occurs from viral infection of the laryngeal epithelial lining associated with a typical cold. The viral infection is almost always quickly conquered by the body's immune system and lasts at most a few days. This kind of acute laryngitis rarely causes any long-term problem unless the vocal folds are damaged by overuse during the illness. Examination of the larynx will show whether the vocal folds are inflamed and allows some prediction of the degree of risk for damage. Other infections of the larynx are fortunately not common but include infections with bacteria and other organisms. -

Incidence of Underlying Laryngeal Pathology in Patients Initially Diagnosed with Laryngopharyngeal Reflux

The Laryngoscope VC 2013 The American Laryngological, Rhinological and Otological Society, Inc. Incidence of Underlying Laryngeal Pathology in Patients Initially Diagnosed With Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Benjamin Rafii, MD; Salvatore Taliercio, MD; Stratos Achlatis, MD; Ryan Ruiz, BA; Milan R. Amin, MD; Ryan C. Branski, PhD Objectives/Hypothesis: To characterize the videoendoscopic laryngeal findings in patients with a prior established diagnosis of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease (LPR) as the sole etiology for their chief complaint of hoarseness. We hypothe- sized that many, if not all, of these patients would present with discrete laryngeal pathology, divergent from LPR. Study Design: Prospective, nonintervention. Methods: Patients presenting to a tertiary laryngology practice with an established diagnosis of LPR as the sole etiology of their hoarseness were included. All subjects completed the Voice Handicap Index and Reflux Symptom Index, in addition to a questionnaire regarding their reflux diagnosis and prior treatment. Laryngoscopic examinations were reviewed by the lar- yngologist caring for the patients. Reliability of findings was assessed by interpretation of videoendoscopic findings by three outside laryngologists not involved in the care of the patients. Results: Laryngeal pathology distinct from LPR was identified in all 21 patients felt to be causative of the chief com- plaint of dysphonia. Specifically, the most common findings were benign mucosal lesions and vocal fold paresis (29% each), followed by muscle tension dysphonia (14%). Two patients were found to have vocal fold leukoplakia, of which one was con- firmed to be a microinvasive carcinoma upon removal. Conclusion: LPR may be overdiagnosed; other etiologies must be considered for patients with hoarseness who fail empiric LPR treatment. -

Parent's Guide to a Sore Throat

Contact your GP (or call 111) Useful contacts: again Your GP surgery on:....................................... Although in most cases the sore throat (Please insert surgery number here) improves in few days, please contact the GP if any of the following occurs: GP Out of Hours: (After 6.30pm and before 8am). Ring 111 and you can speak to a 1. Your child persistently refuses oral fl uids doctor. If necessary, your child can be seen and has not passed urine for over 18 at one of their centres. Parent’s guide hours. Bristol City Walk-in Centre at Broadmead 2. The fever does not settle within four or to a sore throat Medical Centre located in Boots fi ve days. (Mon-Sat 8am-8pm, Sundays and Bank Holidays 11am-5pm) on: 0117 954 9828 3. Your child develops diffi culty in swallowing despite regular paracetamol South Bristol NHS Community Hospital or ibuprofen. Urgent Care Centre (Every day 8am-8pm) on: 0117 342 9692 4. Your child starts drooling because they Visit www.nhs.uk to fi nd your nearest cannot swallow their saliva. centre. Call 999 If your child is seriously ill, you may be asked to attend the Children’s Hospital If your child develops severe breathing emergency department. diffi culties For further copies of this leafl et, or if you would like it in other formats or languages, please contact 0117 900 2384. Produced in partnership with Bristol Clinical Commissioning Group, North Bristol NHS Trust and University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust. End date: June 2016 Your child has been diagnosed with a sore What is the treatment of a sore throat which is very common in children. -

Influenza (Flu) Information and Advice for Patients Infection Prevention and Control

Influenza (flu) Information and advice for patients Infection Prevention and Control What is influenza? Influenza (also known as flu) is a respiratory illness which is caused by the influenza virus. For most people influenza is just a nasty experience, but for some it can lead to illnesses that are more serious such as bronchitis and pneumonia. These illnesses may require treatment in hospital and can be life-threatening especially in the elderly, asthmatics and those in poor health. Most people confuse influenza with a heavy cold; however influenza is usually a more severe illness than the common cold. What are the symptoms of influenza? The most common symptoms of influenza are a quick onset of: • fever • shivering • headache • muscle ache • dry cough The symptoms of a cold are different as they usually occur gradually and include a runny nose, sneezing, watery eyes and throat irritation. A cold does not cause a fever or body aches. What causes influenza? Influenza is caused by the influenza (flu) virus. There are 2 main types that cause infection: influenza A and influenza B. Influenza A is usually a more severe infection than influenza B. Each year 1 or 2 subtypes (strains) of influenza A may be in circulation and 1 type of influenza B. Influenza C is an uncommon type that infrequently causes infection. How does influenza spread? The flu virus is highly contagious and is easily passed from person-to-person when an infected person coughs or sneezes, releasing infected droplets into the air. These droplets then land on surfaces and can be picked up by others who touch them. -

Sore Throats

Sore Throats Insight into relief for a sore throat • What causes a sore throat? • What are my treatment options? • How can I prevent a sore throat? • and more... Infections from viruses or bacteria are the main cause of sore throats and can make it difficult to talk and breathe. Allergies and sinus infections can also contribute to a sore throat. If you have a sore throat that lasts for more than five to seven days, you should see your doctor. While increasing your liquid intake, gargling with warm salt water, or taking over-the-counter pain relievers may help, if appropriate, your doctor may write you a prescription for an antibiotic. What are the causes and symptoms of a sore throat? Infections by contagious viruses or bacteria are the source of the majority of sore throats. Viruses: Sore throats often accompany viral infections, including the flu, colds, measles, chicken pox, whooping cough, and croup. One viral infection, infectious mononucleosis, or “mono,” takes much longer than a week to be cured. This virus lodges in the lymph system, causing massive enlargement of the tonsils, with white patches on their surface. Other symptoms include swollen glands in the neck, armpits, and groin; fever, chills, and headache. If you are suffering from mono, you will likely experience a severe sore throat that may last for one to four weeks and, sometimes, serious breathing difficulties. Mono causes extreme fatigue that can last six weeks or more, and can also affect the liver, leading to jaundice-yellow skin and eyes. Bacteria: Strep throat is an infection caused by a particular strain of streptococcus bacteria. -

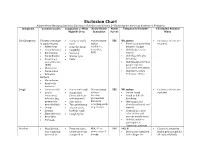

Exclusion Chart

Exclusion Chart Adapted from Managing Infectious Diseases in Child Care and Schools, 3rd Edition by the American Academy of Pediatrics Symptoms Common Causes Complaints or What Notify Health Notify Temperarily Exclude? If Excluded, Readmit Might Be Seen Consultant Parent When Cold Symptoms Viruses (early stage • Runny or stuffy Not necessary YES NO, unless: • Exclusion criteria are of many viruses) nose unless • Fever accompanied by resolved. • Adenovirus • Scratchy throat epidemics behavior change • Coxsackievirus • Coughing occur (i.e., • Child looks or acts • Enterovirus • Sneezing RSV) very ill • Parainfluenza • Watery eyes • Child has difficulty • Respiratory • Fever breathing syncytial virus • Child has blood-red or (RSV) purple rash not • Rhinovirus associated with injury • Coronavirus • Child meets other • Influenza exclusion criteria Bacteria • Mycoplasma • Bordetella pertussis Cough • Common cold • Dry or wet cough Not necessary YES NO, unless: • Exclusion criteria are • Lower • Runny nose unless a • Severe cough resolved respiratory (clear, white, or vaccine- • Rapid or difficult infection (e.g., yellow-green) preventable breathing pneumonia, • Sore throat disease is • Wheezing if not bronchiolitis) • Throat irritation occurring, such already evaluated and • Croup • Hoarse voice, as pertussis treated • Asthma barking cough • Cyanosis (i.e., blue • Sinus infection • Coughing fits color of skin and • Bronchitis mucous membranes) • Pertussis • Child is unable to participate in classroom activities Diarrhea • Usually viral, • Frequent -

Biofeedback in Dysphonia – Progress and Challenges

Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;84(2):240---248 Brazilian Journal of OTORHINOLARYNGOLOGY www.bjorl.org REVIEW ARTICLE ଝ Biofeedback in dysphonia --- progress and challenges a,∗ b Geová Oliveira de Amorim , Patrícia Maria Mendes Balata , c a a Laís Guimarães Vieira , Thaís Moura , Hilton Justino da Silva a Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE), Recife, PE, Brazil b Hospital dos Servidores do Estado de Pernambuco, Recife, PE, Brazil c LGV Assessoria e Consultoria Médica, Recife, PE, Brazil Received 11 January 2016; accepted 15 July 2017 Available online 19 August 2017 KEYWORDS Abstract Introduction: There is evidence that all the complex machinery involved in speech acts along Speech therapy; Voice; with the auditory system, and their adjustments can be altered. Objective: Dysphonia; To present the evidence of biofeedback application for treatment of vocal disorders, Electromyography emphasizing the muscle tension dysphonia. Methods: feedback A systematic review was conducted in Scielo, Lilacs, PubMed and Web of Sciences databases, using the combination of descriptors, and admitting as inclusion criteria: articles published in journals with editorial committee, reporting cases or experimental or quasi- experimental research on the use of biofeedback in real time as additional source of treatment monitoring of muscle tension dysphonia or for vocal training. Results: Thirty-three articles were identified in databases, and seven were included in the qual- itative synthesis. The beginning of electromyographic biofeedback studies applied to -

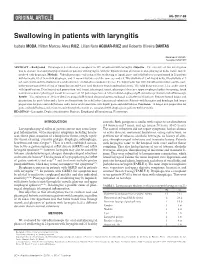

Swallowing in Patients with Laryngitis

AG-2017-86 AHEADORIGINAL OF ARTICLEPRINT dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0004-2803.201800000-10 Swallowing in patients with laryngitis Isabela MODA, Hilton Marcos Alves RICZ, Lilian Neto AGUIAR-RICZ and Roberto Oliveira DANTAS Received 21/8/2017 Accepted 5/10/2017 ABSTRACT – Background – Dysphagia is described as a complaint in 32% of patients with laryngitis. Objective – The objective of this investigation was to evaluate oral and pharyngeal transit of patients with laryngitis, with the hypothesis that alteration in oral-pharyngeal bolus transit may be involved with dysphagia. Methods – Videofluoroscopic evaluation of the swallowing of liquid, paste and solid boluses was performed in 21 patients with laryngitis, 10 of them with dysphagia, and 21 normal volunteers of the same age and sex. Two swallows of 5 mL liquid bolus, two swallows of 5 mL paste bolus and two swallows of a solid bolus were evaluated in a random sequence. The liquid bolus was 100% liquid barium sulfate and the paste bolus was prepared with 50 mL of liquid barium and 4 g of food thickener (starch and maltodextrin). The solid bolus was a soft 2.2 g cookie coated with liquid barium. Durations of oral preparation, oral transit, pharyngeal transit, pharyngeal clearance, upper esophageal sphincter opening, hyoid movement and oral-pharyngeal transit were measured. All patients performed 24-hour distal esophageal pH evaluation previous to videofluoroscopy. Results – The evaluation of 24-hour distal esophageal pH showed abnormal gastroesophageal acid reflux in 10 patients. Patients showed longer oral preparation for paste bolus and a faster oral transit time for solid bolus than normal volunteers. -

EUA) of REGEN-COVTM (Casirivimab and Imdevimab

FACT SHEET FOR HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION (EUA) OF REGEN-COVTM (casirivimab and imdevimab) AUTHORIZED USE TREATMENT The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to permit the emergency use of the unapproved product, REGEN-COV (casirivimab and imdevimab) co-formulated product and REGEN-COV (casirivimab and imdevimab) supplied as individual vials to be administered together, for the treatment of mild to moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in adult and pediatric patients (12 years of age and older weighing at least 40 kg) with positive results of direct SARS-CoV-2 viral testing, and who are at high risk for progression to severe COVID-19, including hospitalization or death. Limitations of Authorized Use • REGEN-COV (casirivimab and imdevimab) is not authorized for use in patients: - who are hospitalized due to COVID-19, OR - who require oxygen therapy due to COVID-19, OR - who require an increase in baseline oxygen flow rate due to COVID-19 in those on chronic oxygen therapy due to underlying non-COVID-19 related comorbidity. • Monoclonal antibodies, such as REGEN-COV, may be associated with worse clinical outcomes when administered to hospitalized patients with COVID-19 requiring high flow oxygen or mechanical ventilation. POST-EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to permit the emergency use of the unapproved product, REGEN-COV (casirivimab and imdevimab) co-formulated product and REGEN-COV -

Patient Information for Influenza and Respiratory Viruses

Patient information for Influenza and Respiratory Viruses UHB is a no smoking Trust To see all of our current patient information leaflets please visit www.uhb.nhs.uk/patient-information-leaflets.htm A respiratorr virus is an illness that infects the respiratorr (breathing) srstem. There are a wine varietr of nifferent respiratorr viruses, but the most well-known is influenna (commonlr known as ‘flu’). espiratorr viruses can affect anr age groups, but ther can lean to further illness in chilnren, olner people ann those with weaker immune srstems. Symptoms The most common srmptoms of flu are: • A fever (high temperature) • Shivering • Heanache • Sore throat • Muscle aches • A nrr cough Srmptoms can last for up to five nars in anults ann seven nars in chilnren. Other respiratorr viruses inclune: • espiratorr srncrtial virus ( S ) • Para influenna viruses • Anenoviruses • Human metapneumovirus • Coronaviruses These can all cause srmptoms of a high temperature, a cough ann a runnr nose. 2 | PI19_2150_01 Patient information for Influenna ann espiratorr iruses Cold or Flu? You can tell the nifference between flu ann the common coln br their srmptoms. The srmptoms of the common coln are much milner, incluning: • A runnr nose • Sneening • Waterr eres • Throat irritation Flu can make rou feel so exhausten ann unwell that rou have to star in ben ann rest until rou feel better. How do respiratory viruses spread? espiratorr viruses sprean easilr from one person to another. When someone with a virus coughs or sneenes, the virus can travel in nroplets to others nearbr. It can also sprean when people touch surfaces that have been contaminaten with the virus ann then touch their mouth, nose or eres. -

Download PDF File

GUIDELINES AND RECOMMENDATIONSPRACA ORYGINALNA Henryk Mazurek1, 2, Anna Bręborowicz3, Zbigniew Doniec4, Andrzej Emeryk5, Katarzyna Krenke6, Marek Kulus6, Beata Zielnik-Jurkiewicz7 1Department of Pneumonology and Cystic Fibrosis, Institute of Tuberculosis and Pulmonary Diseases, Rabka-Zdrój, Poland 2State Higher Vocational School, Nowy Sącz, Poland 3Department of Pneumonology, Pediatric Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Poznan University of Medical Science, Poznań, Poland 4Department of Pneumonology, Institute of Tuberculosis and Pulmonary Diseases, Rabka-Zdrój, Poland 5Department of Pulmonary Diseases and Children Rheumatology, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland 6Department of Pediatric Pneumonology and Allergy, Medical University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland 7Department of Otolaryngology, Children’s Hospital, Warsaw, Poland Acute subglottic laryngitis. Etiology, epidemiology, pathogenesis and clinical picture Abstract In about 3% of children, viral infections of the airways that develop in early childhood lead to narrowing of the laryngeal lumen in the subglottic region resulting in symptoms such as hoarseness, a barking cough, stridor, and dyspnea. These infections may eventually cause respiratory failure. The disease is often called acute subglottic laryngitis (ASL). Terms such as pseudocroup, croup syndrome, acute obstructive laryngitis and spasmodic croup are used interchangeably when referencing this disease. Although the differential diagnosis should include other rare diseases such as epiglottitis, diphtheria, fibrinous laryngitis and bacterial tracheobronchitis, the diagnosis of ASL should always be made on the basis of clinical criteria. Key words: subglottic laryngitis, croup, laryngeal obstruction, inspiratory dyspnoea, stridor Adv Respir Med. 2019; 87: 308–316 Definition and nomenclature have in common is laryngitis. However, some of them also indicate the location of the lesions In approximately 3% of children [1, 2], or their pathological background (e.g.