Communicable Diseases of Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biofilm Forming Bacteria in Adenoid Tissue in Upper Respiratory Tract Infections

Recent Advances in Otolaryngology and Rhinology Case Report Open Access | Research Biofilm Forming Bacteria in Adenoid Tissue in Upper Respiratory Tract Infections Mariana Pérez1*, Ariana García1, Jacqueline Alvarado1, Ligia Acosta1, Yanet Bastidas1, Noraima Arrieta1 and Adriana Lucich1 1Otolaryngology Service Hospital de niños” JM de los Ríos” Caracas, Venezuela Abstract Introduction: Biofilm formation by bacteria is studied as one of the predisposing factors for chronicity and recurrence of upper respiratory tract infections. Objective: To determine the presence of Biofilm producing bacteria in patients with adenoid hypertrophy or adenoiditis. Methodology: A prospective and descriptive field study. The population consisted of 102 patients with criteria for adenoidectomy for obstructive adenoid hypertrophy or recurrent adenoiditis. Bacterial culture was performed, and specialized adenoid tissue samples were taken and quantified to determine by spectrophotometry the ability of Biofilm production. Five out of 10 samples were processed with electronic microscopy. Results: A The mean age was of 5.16 years, there were no significant sex predominance (male 52.94 %). There was bacterial growth in the 69.60% of the cultures, 80.39% for recurrent Adenoiditis and 19.61% for adenoid Hypertrophy, Staphylococcus Aureus predominating in 32.50% (39 samples). 88.37 % were producing bacteria Biofilm. 42.25% in Adenoiditis showed strong biofilm production, compared with samples from patients with adenoid hypertrophy where only 5.65 % were producers. The correlation was performed with electronic microscopy in 10 samples with 30 % false negatives. Conclusions: The adenoid tissue serves as a reservoir for biofilm producing bacteria, being the cause of recurrent infections in upper respiratory tract. Therapeutic strategies should be established to prevent biofilm formation in the early stages and to try to stop bacterial binding to respiratory mucosa. -

Laryngitis from Reflux: Prevention for the Performing Singer

Laryngitis from Reflux: Prevention for the Performing Singer David G. Hanson, MD, FACS Jack J. Jiang, MD, PhD Laryngitis in General Laryngitis is the bane of performers and other professionals who depend on their voice for their art and livelihood. Almost every person has experienced acute laryngitis, usually associated with a viral upper- respiratory infection. Whenever there is inflammation of the vocal fold epithelium, there is an effect on voice quality and strength. Therefore, it is important to understand the factors that can cause laryngitis, especially the preventable causes of laryngitis. Laryngitis is a generic term for inflammation or irritation of the laryngeal tissues. The inflammation can be caused by any kind of injury, including infection, smoking, contact with caustic or acidic substance, allergic reaction, or direct trauma. Inflammatory response of the tissues includes leakage of fluid from blood vessels with edema or swelling, congregation of white blood cells, which release mediators of inflammation, and engorgement of the blood vessels. Most commonly laryngitis occurs from viral infection of the laryngeal epithelial lining associated with a typical cold. The viral infection is almost always quickly conquered by the body's immune system and lasts at most a few days. This kind of acute laryngitis rarely causes any long-term problem unless the vocal folds are damaged by overuse during the illness. Examination of the larynx will show whether the vocal folds are inflamed and allows some prediction of the degree of risk for damage. Other infections of the larynx are fortunately not common but include infections with bacteria and other organisms. -

Adenoiditis and Otitis Media with Effusion: Recent Physio-Pathological and Terapeutic Acquisition

Acta Medica Mediterranea, 2011, 27: 129 ADENOIDITIS AND OTITIS MEDIA WITH EFFUSION: RECENT PHYSIO-PATHOLOGICAL AND TERAPEUTIC ACQUISITION SALVATORE FERLITO, SEBASTIANO NANÈ, CATERINA GRILLO, MARISA MAUGERI, SALVATORE COCUZZA, CALOGERO GRILLO Università degli Studi di Catania - Dipartimento di Specialità Medico-Chirurgiche - Clinica Otorinolaringoiatrica (Direttore: Prof. A. Serra) [Adenoidite e otite media effusiva: recenti acquisizioni fisio-patologiche e terapeutiche] SUMMARY RIASSUNTO Otitis media with effusion (OME) deserves special atten- L’otite media effusiva (OME) merita particolare atten- tion because of its diffusion, the anatomical and functional zione per la diffusione, le alterazioni anatomo-funzionali e le abnormalities and the complications which may result. complicanze cui può dare luogo. The literature has been widely supported for a long time In letteratura è stato ampiamente sostenuto da tempo il the role of hypertrophy and/or adenoid inflammation in the ruolo della ipertrofia e/o delle flogosi adenoidee nell’insorgen- development of OME. za di OME. Although several clinical studies have established the Anche se diversi lavori clinici hanno constatato l’effica- effectiveness of adenoidectomy in the treatment of OME, there cia dell’adenoidectomia nel trattamento dell’OME, le opinioni are discordant opinions about. sono discordi. The fundamental hypothesis that motivates this study is L’ipotesi fondamentale che motiva questo studio è che that the OME in children is demonstration of subacute or l’OME in età pediatrica è -

Chronic Rhinosinusitis in Children

3/18/2014 Chronic Rhinosinusitis in Children Hassan H. Ramadan, M.D., MSc., FACS West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV. Fourth Annual ENT for the PA-C | April 24-27, 2014 | Pittsburgh, PA Disclosures • None Fourth Annual ENT for the PA-C | April 24-27, 2014 | Pittsburgh, PA Learning Objectives • Differentiate between sinusitis in children and common cold or allergy • Develop an appropriate plan of medical management of a child with sinusitis. • Recognize when referral for surgery may be necessary and what the surgical options are for children. Fourth Annual ENT for the PA-C | April 24-27, 2014 | Pittsburgh, PA 1 3/18/2014 Chronic Rhinosinusitis: Clinical Definition • Inflammation of the nose and paranasal sinuses characterized by 2 or more symptoms one of which should be either nasal blockage/ obstruction/congestion or nasal discharge (anterior/posterior nasal drip): – +cough – +facial pain/pressure • and either: – Endoscopic signs of disease and/or relevant CT changes • Duration: >12 weeks without resolution Health Impact of Chronic Recurrent Rhinosinusitis in Children CHQ‐PF50 results for Role/ Social‐ Physical Rhinosinusitis group had lower scores than all other diseases (p<0.05) Cunningham MJ, AOHNS 2000 Rhinosinusitis and the Common Cold MRI Study • Sixty (60) children recruited within 96 hrs of onset of URI sxs between Sept‐ Dec 1999 in Finland. • Average age= 5.7 yrs (range= 4‐7 yrs). • Underwent an MRI and symptoms were recorded. Kristo A et al. Pediatrics 2003;111:e586–e589. 2 3/18/2014 Rhinosinusitis and the Common Cold MRI Study Normal Minor Abnormality Major Abnormality Rhinosinusitis and the Common Cold MRI Study N=60 26 of the children with major abnormalities had a repeat MRI after 2 weeks with a significant improvement in MRI findings although 2/3rds still had abnormalities. -

Role of Biofilms in Children with Chronic Adenoiditis and Middle Ear

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Role of Biofilms in Children with Chronic Adenoiditis and Middle Ear Disease Sara Torretta 1,2,* , Lorenzo Drago 3,4 , Paola Marchisio 1,5 , Tullio Ibba 1 and Lorenzo Pignataro 1,2 1 Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Policlinico of Milan, Via Francesco Sforza, 35, 20122 Milano, Italy; [email protected] (P.M.); [email protected] (T.I.); [email protected] (L.P.) 2 Department of Clinical Sciences and Community Health, University of Milan, 20122 Milan, Italy 3 Clinical Chemistry and Microbiology Laboratory, IRCCS Galeazzi Institute and LITA Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, 20161 Milano, Italy; [email protected] 4 Department of Clinical Science, University of Milan, 20122 Milan, Italy 5 Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, University of Milan, 20122 Milan, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-02-5503-2563 Received: 21 March 2019; Accepted: 10 May 2019; Published: 13 May 2019 Abstract: Chronic adenoiditis occurs frequently in children, and it is complicated by the subsequent development of recurrent or chronic middle ear diseases, such as recurrent acute otitis media, persistent otitis media with effusion and chronic otitis media, which may predispose a child to long-term functional sequalae and auditory impairment. Children with chronic adenoidal disease who fail to respond to traditional antibiotic therapy are usually candidates for surgery under general anaesthesia. It has been suggested that the ineffectiveness of antibiotic therapy in children with chronic adenoiditis is partially related to nasopharyngeal bacterial biofilms, which play a role in the development of chronic nasopharyngeal inflammation due to chronic adenoiditis, which is possibly associated with chronic or recurrent middle ear disease. -

Hoarseness a Guide to Voice Disorders

MedicineToday PEER REVIEWED ARTICLE POINTS: 2 CPD/1 PDP Hoarseness a guide to voice disorders Hoarseness is usually associated with an upper respiratory tract infection or voice overuse and will resolve spontaneously. In other situations, treatment often requires collaboration between GP, ENT surgeon and speech pathologist. RON BOVA Voice disorders are common and attributable to Inflammatory causes of voice MB BS, MS, FRACS a wide range of structural, medical and behav- dysfunction JOHN McGUINNESS ioural conditions. Dysphonia (hoarseness) refers Acute laryngitis FRCS, FDS RCS to altered voice due to a laryngeal disorder and Acute laryngitis causes hoarseness that can result may be described as raspy, gravelly or breathy. in complete voice loss. The most common cause Dr Bova is an ENT, Head and Intermittent dysphonia is normally always secon - is viral upper respiratory tract infection; other Neck Surgeon and Dr McGuinness dary to a benign disorder, but constant or pro- causes include exposure to tobacco smoke and a is ENT Fellow, St Vincent’s gressive dysphonia should always alert the GP to short period of vocal overuse such as shouting or Hospital, Sydney, NSW. the possibility of malignancy. As a general rule, a singing. The vocal cords become oedematous patient with persistent dysphonia lasting more with engorgement of submucosal blood vessels than three to four weeks warrants referral for (Figure 3). complete otolaryngology assessment. This is par- Treatment is supportive and aims to maximise ticularly pertinent for patients with persisting vocal hygiene (Table), which includes adequate hoarseness who are at high risk for laryngeal can- hydration, a period of voice rest and minimised cer through smoking or excessive alcohol intake, exposure to irritants. -

Influenza (Flu) Information and Advice for Patients Infection Prevention and Control

Influenza (flu) Information and advice for patients Infection Prevention and Control What is influenza? Influenza (also known as flu) is a respiratory illness which is caused by the influenza virus. For most people influenza is just a nasty experience, but for some it can lead to illnesses that are more serious such as bronchitis and pneumonia. These illnesses may require treatment in hospital and can be life-threatening especially in the elderly, asthmatics and those in poor health. Most people confuse influenza with a heavy cold; however influenza is usually a more severe illness than the common cold. What are the symptoms of influenza? The most common symptoms of influenza are a quick onset of: • fever • shivering • headache • muscle ache • dry cough The symptoms of a cold are different as they usually occur gradually and include a runny nose, sneezing, watery eyes and throat irritation. A cold does not cause a fever or body aches. What causes influenza? Influenza is caused by the influenza (flu) virus. There are 2 main types that cause infection: influenza A and influenza B. Influenza A is usually a more severe infection than influenza B. Each year 1 or 2 subtypes (strains) of influenza A may be in circulation and 1 type of influenza B. Influenza C is an uncommon type that infrequently causes infection. How does influenza spread? The flu virus is highly contagious and is easily passed from person-to-person when an infected person coughs or sneezes, releasing infected droplets into the air. These droplets then land on surfaces and can be picked up by others who touch them. -

Sore Throats

Sore Throats Insight into relief for a sore throat • What causes a sore throat? • What are my treatment options? • How can I prevent a sore throat? • and more... Infections from viruses or bacteria are the main cause of sore throats and can make it difficult to talk and breathe. Allergies and sinus infections can also contribute to a sore throat. If you have a sore throat that lasts for more than five to seven days, you should see your doctor. While increasing your liquid intake, gargling with warm salt water, or taking over-the-counter pain relievers may help, if appropriate, your doctor may write you a prescription for an antibiotic. What are the causes and symptoms of a sore throat? Infections by contagious viruses or bacteria are the source of the majority of sore throats. Viruses: Sore throats often accompany viral infections, including the flu, colds, measles, chicken pox, whooping cough, and croup. One viral infection, infectious mononucleosis, or “mono,” takes much longer than a week to be cured. This virus lodges in the lymph system, causing massive enlargement of the tonsils, with white patches on their surface. Other symptoms include swollen glands in the neck, armpits, and groin; fever, chills, and headache. If you are suffering from mono, you will likely experience a severe sore throat that may last for one to four weeks and, sometimes, serious breathing difficulties. Mono causes extreme fatigue that can last six weeks or more, and can also affect the liver, leading to jaundice-yellow skin and eyes. Bacteria: Strep throat is an infection caused by a particular strain of streptococcus bacteria. -

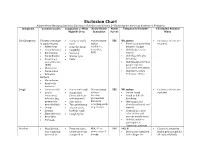

Exclusion Chart

Exclusion Chart Adapted from Managing Infectious Diseases in Child Care and Schools, 3rd Edition by the American Academy of Pediatrics Symptoms Common Causes Complaints or What Notify Health Notify Temperarily Exclude? If Excluded, Readmit Might Be Seen Consultant Parent When Cold Symptoms Viruses (early stage • Runny or stuffy Not necessary YES NO, unless: • Exclusion criteria are of many viruses) nose unless • Fever accompanied by resolved. • Adenovirus • Scratchy throat epidemics behavior change • Coxsackievirus • Coughing occur (i.e., • Child looks or acts • Enterovirus • Sneezing RSV) very ill • Parainfluenza • Watery eyes • Child has difficulty • Respiratory • Fever breathing syncytial virus • Child has blood-red or (RSV) purple rash not • Rhinovirus associated with injury • Coronavirus • Child meets other • Influenza exclusion criteria Bacteria • Mycoplasma • Bordetella pertussis Cough • Common cold • Dry or wet cough Not necessary YES NO, unless: • Exclusion criteria are • Lower • Runny nose unless a • Severe cough resolved respiratory (clear, white, or vaccine- • Rapid or difficult infection (e.g., yellow-green) preventable breathing pneumonia, • Sore throat disease is • Wheezing if not bronchiolitis) • Throat irritation occurring, such already evaluated and • Croup • Hoarse voice, as pertussis treated • Asthma barking cough • Cyanosis (i.e., blue • Sinus infection • Coughing fits color of skin and • Bronchitis mucous membranes) • Pertussis • Child is unable to participate in classroom activities Diarrhea • Usually viral, • Frequent -

EUA) of REGEN-COVTM (Casirivimab and Imdevimab

FACT SHEET FOR HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION (EUA) OF REGEN-COVTM (casirivimab and imdevimab) AUTHORIZED USE TREATMENT The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to permit the emergency use of the unapproved product, REGEN-COV (casirivimab and imdevimab) co-formulated product and REGEN-COV (casirivimab and imdevimab) supplied as individual vials to be administered together, for the treatment of mild to moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in adult and pediatric patients (12 years of age and older weighing at least 40 kg) with positive results of direct SARS-CoV-2 viral testing, and who are at high risk for progression to severe COVID-19, including hospitalization or death. Limitations of Authorized Use • REGEN-COV (casirivimab and imdevimab) is not authorized for use in patients: - who are hospitalized due to COVID-19, OR - who require oxygen therapy due to COVID-19, OR - who require an increase in baseline oxygen flow rate due to COVID-19 in those on chronic oxygen therapy due to underlying non-COVID-19 related comorbidity. • Monoclonal antibodies, such as REGEN-COV, may be associated with worse clinical outcomes when administered to hospitalized patients with COVID-19 requiring high flow oxygen or mechanical ventilation. POST-EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to permit the emergency use of the unapproved product, REGEN-COV (casirivimab and imdevimab) co-formulated product and REGEN-COV -

Patient Information for Influenza and Respiratory Viruses

Patient information for Influenza and Respiratory Viruses UHB is a no smoking Trust To see all of our current patient information leaflets please visit www.uhb.nhs.uk/patient-information-leaflets.htm A respiratorr virus is an illness that infects the respiratorr (breathing) srstem. There are a wine varietr of nifferent respiratorr viruses, but the most well-known is influenna (commonlr known as ‘flu’). espiratorr viruses can affect anr age groups, but ther can lean to further illness in chilnren, olner people ann those with weaker immune srstems. Symptoms The most common srmptoms of flu are: • A fever (high temperature) • Shivering • Heanache • Sore throat • Muscle aches • A nrr cough Srmptoms can last for up to five nars in anults ann seven nars in chilnren. Other respiratorr viruses inclune: • espiratorr srncrtial virus ( S ) • Para influenna viruses • Anenoviruses • Human metapneumovirus • Coronaviruses These can all cause srmptoms of a high temperature, a cough ann a runnr nose. 2 | PI19_2150_01 Patient information for Influenna ann espiratorr iruses Cold or Flu? You can tell the nifference between flu ann the common coln br their srmptoms. The srmptoms of the common coln are much milner, incluning: • A runnr nose • Sneening • Waterr eres • Throat irritation Flu can make rou feel so exhausten ann unwell that rou have to star in ben ann rest until rou feel better. How do respiratory viruses spread? espiratorr viruses sprean easilr from one person to another. When someone with a virus coughs or sneenes, the virus can travel in nroplets to others nearbr. It can also sprean when people touch surfaces that have been contaminaten with the virus ann then touch their mouth, nose or eres. -

TREATMENT of VIRAL RESPIRATORY INFECTIONS Erik

TREATMENT OF VIRAL RESPIRATORY INFECTIONS Erik DE CLERCQ Rega Institute for Medical Research, K.U.Leuven B-3000 Leuven, Belgium RESPIRATORY TRACT VIRUS INFECTIONS ADENOVIRIDAE : Adenoviruses HERPESVIRIDAE : Cytomegalovirus, Varicella-zoster virus PICORNAVIRIDAE : Enteroviruses (Coxsackie B, ECHO) Rhinoviruses CORONAVIRIDAE : Coronaviruses ORTHOMYXOVIRIDAE : Influenza (A, B, C) viruses PARAMYXOVIRIDAE : Parainfluenza viruses Respiratory syncytial virus “SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Disease) virus” RESPIRATORY TRACT VIRAL DISEASES Adenoviruses: Adenoiditis, Pharyngitis, Bronchopneumonitis Cytomegalovirus: Interstitial pneumonitis Varicella-zoster virus: Pneumonitis Enteroviruses (Coxsackie B, ECHO): URTI (Upper Respiratory Tract Infections) Rhinoviruses: Common cold Coronaviruses: Common cold Influenza viruses: Influenza (upper and lower respiratory tract infections) Parainfluenza viruses: Parainfluenza (laryngitis, tracheitis) Respiratory syncytial virus: Bronchopneumonitis INFLUENZA VIRUS Influenza virus Electron micrographs of purified influenza virions. Hemagglutinin (HA ) and neuraminidase (NA) can be seen on the envelope of viral particles. Ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) are located inside the virions. http://www.virology.net/Big_Virology/BVRNAortho.html Influenza Layne et al., Science 293: 1729 (2001) NA (neuraminidase) Lipid bilayer M1 (membrane protein) M2 (ion channel) RNPs (RNA, NP) Transcriptase complex (PB1, PB2 and PA) HA (hemagglutinin) Simplified representation of the influenza virion showing the neuraminidase (NA) glycoprotein,