Corporate Capture 1 2 Published in September 2018 by the Alliance for Lobbying Transparency and Ethics Regulation in the EU (ALTER-EU)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aangifte Tegen Vijf (Oud-)Bewindslieden in Toeslagenaffaire

NIEUWS 12 januari 2021 Aangifte tegen vijf (oud-)bewindslieden in toeslagenaffaire Advocaat Vasco Groeneveld heeft dinsdag namens twintig gedupeerden in de kindertoeslaga aire aangifte gedaan tegen vijf (oud-)bewindslieden, onder wie de ministers Tamara van Ark (Medische Zorg), Wopke Hoekstra (Financiën) en Eric Wiebes (Economische Zaken). Volgens Groeneveld hebben zij zich schuldig gemaakt aan een ambtsmisdrijf. Naast de drie ministers heeft de raadsman Menno Snel, voormalig staatssecretaris van Financiën, en Lodewijk Asscher (voorheen minister van Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid) in de aangifte betrokken. De aangifte is gedaan bij de procureur-generaal van de Hoge Raad, omdat het om (oud-)bewindslieden gaat. De advocaat stelt dat de (oud-)bewindslieden strafrechtelijk verwijtbaar hebben gehandeld, door na te laten wettelijke bepalingen uit te voeren, terwijl dat tot hun taak behoorde. Het gaat daarbij om een aantal beginselen van "behoorlijk bestuur", waaronder het fair play-beginsel en het zorgvuldigheidsbeginsel. De bewindslieden hadden volgens de raadsman moeten voorkomen dat de Belastingdienst zich schuldig maakte aan zogeheten knevelarij en beroepsmatige discriminatie. Ook zijn artikel 1 van de Grondwet (het gelijkheidsbeginsel) en het Internationaal verdrag inzake de rechten van het kind geschonden. Parlementaire rapport Het vernietigende parlementaire rapport dat over de a aire is uitgebracht, vormt een belangrijke basis voor de aangifte. Volgens Groeneveld blijkt uit het rapport dat de betrokken (oud-)bewindslieden over "zodanig verontrustende informatie" beschikten dat zij hadden moeten ingrijpen. "Zeker vanaf het verschijnen van het kritische rapport van de Nationale Ombudsman, onder de titel ‘Geen powerplay maar fair play’, in augustus 2017, stond het sein op rood", zegt Groeneveld. Maar ook eerder waren er al belangrijke signalen, stelt hij, maar ging het onrechtmatig invorderen door de Belastingdienst tot in elk geval eind 2019 door. -

President Barroso Presents the Commissioner Designate for Bulgaria

IP/06/1485 Brussels, 26 October 2006 President Barroso presents the Commissioner designate for Bulgaria The President of the European Commission, José Manuel Barroso, today presented the designated member of the European Commission proposed by the Bulgarian Government, in agreement with him. The nomination is Ms Meglena Kuneva, the current Bulgarian Minister for European Affairs. Ms Kuneva will be responsible for consumer protection. « I am delighted to welcome among us» said President Barroso, « the Bulgarian Commissioner designate. From next January, the European Union of 27 will become a reality and that reality will be reflected in the composition of the Commission. I am convinced that Ms Kuneva has the professional and political qualities, as well as the personal commitment and necessary experience to accomplish all the tasks which I am proposing to make her responsible for. » The Bulgarian Commissioner designate along with the Romanian Commissioner – yet to be designated - will attend hearings at the end of November in the European Parliament, which will give its opinion on the nomination in the following weeks. The hearings before the Parliament will take place according to the procedure adopted in 2004 during the formation of the Barroso Commission. The consultations for the designation of the Romanian Commissioner are still ongoing. The curriculum vitae of Ms Kuneva can be found in annex. See also the Memo/06/401 which sets out the procedures for nomination. Meglena Shtilianova Kuneva Bulgarian Minister for European Affairs Born on 22 June 1957 in Sofia. Master’s degree in Law. Meglena Kuneva graduated from the Faculty of Law at Sofia University St Kliment Ohridski in 1981; awarded PhD in Law in 1984. -

Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past: a Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region

CBEES State of the Region Report 2020 Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past A Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region Published with support from the Foundation for Baltic and East European Studies (Östersjstiftelsen) Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past A Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region December 2020 Publisher Centre for Baltic and East European Studies, CBEES, Sdertrn University © CBEES, Sdertrn University and the authors Editor Ninna Mrner Editorial Board Joakim Ekman, Florence Frhlig, David Gaunt, Tora Lane, Per Anders Rudling, Irina Sandomirskaja Layout Lena Fredriksson, Serpentin Media Proofreading Bridget Schaefer, Semantix Print Elanders Sverige AB ISBN 978-91-85139-12-5 4 Contents 7 Preface. A New Annual CBEES Publication, Ulla Manns and Joakim Ekman 9 Introduction. Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past, David Gaunt and Tora Lane 15 Background. Eastern and Central Europe as a Region of Memory. Some Common Traits, Barbara Trnquist-Plewa ESSAYS 23 Victimhood and Building Identities on Past Suffering, Florence Frhlig 29 Image, Afterimage, Counter-Image: Communist Visuality without Communism, Irina Sandomirskaja 37 The Toxic Memory Politics in the Post-Soviet Caucasus, Thomas de Waal 45 The Flag Revolution. Understanding the Political Symbols of Belarus, Andrej Kotljarchuk 55 Institutes of Trauma Re-production in a Borderland: Poland, Ukraine, and Lithuania, Per Anders Rudling COUNTRY BY COUNTRY 69 Germany. The Multi-Level Governance of Memory as a Policy Field, Jenny Wstenberg 80 Lithuania. Fractured and Contested Memory Regimes, Violeta Davoliūtė 87 Belarus. The Politics of Memory in Belarus: Narratives and Institutions, Aliaksei Lastouski 94 Ukraine. Memory Nodes Loaded with Potential to Mobilize People, Yuliya Yurchuk 106 Czech Republic. -

The European Parliament Elections in Bulgaria Are Likely to Reinforce the Country's Political Stalemate Between Left and Right

The European Parliament elections in Bulgaria are likely to reinforce the country’s political stalemate between left and right blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2014/04/14/the-european-parliament-elections-in-bulgaria-are-likely-to-reinforce- the-countrys-political-stalemate-between-left-and-right/ 14/04/2014 The Bulgarian government currently lacks a majority in the country’s national parliament, with the governing coalition counting on support from 120 out of 240 MPs. Kyril Drezov writes that the upcoming European elections will likely be fought on the basis of this domestic situation, with European issues playing only a minor role, and the majority of seats being distributed between the two largest parties: the Bulgarian Socialist Party and the Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB). European Parliament Elections are still fairly new for Bulgaria – the 2014 elections will be only the third since accession. Like previous EP elections in 2007 and 2009, their function is purely as a test for changes in national politics. The present election campaign is overwhelmingly dominated by domestic concerns and is notable for the absence of EU-related issues. As a leftover from the accession days, the European Union is still considered ‘a good thing’ in Bulgaria and does not generate much passion. There is consensus amongst Bulgarians that key European policies are shaped somewhere else, and that Sofia’s role is to adapt to these policies whatever shape they may take. The big traditional players in Bulgarian politics gravitate towards particular European party families – Socialist, Christian Democratic and Liberal – and in their election manifestoes mostly parrot whatever line these party families take on the big European issues. -

Voorjaarscongres 2017

ledenmagazine van de VVD Jaargang 13 Nummer 4 7 juli 2017 Voorjaarscongres 2017 Het is tijd voor actie! Collegetour: Verre van uitgeregeerd Houd de koffietruck Het Winnende Raadslid op de weg! 3 6 12 15 HET IS TIJD VOOR ACTIE! Colofon Liber is een uitgave van de VVD en verschijnt in principe acht keer per jaar. Kopij volgende editie vóór 11 september 2017. Het is dat u dit stukje leest, want anders kiezingen komen er aan in maart 2018. had het mij niet verbaasd als u niet had Op alle niveaus wordt er al aan de cam- Realisatie: geweten wie de voorzitter van de partij pagne gewerkt. Vrijwel alle netwerken Het is geen geheim. De afgelopen jaren heb- 2018 lid zijn van de VVD. Het is de VVD Algemeen Secretariaat in is. De voorzitter van een partij opereert hebben hun eerste ledenvergadering ge- ben politieke partijen in Nederland te maken ideale mogelijkheid om op een laag- samenwerking met Meere Reclamestudio meestal vooral op de achtergrond en had en procedures vastgesteld; sommige met dalende ledenaantallen. Ook de VVD. Voor drempelige manier kennis te maken en een netwerk van VVD-correspondenten. zorgt er samen met de leden van het lijsttrekkers zijn al gekozen en er wordt Algemeen Secretaris Stephanie ter Borg is het met onze partij. Je bent als intro- Hoofdbestuur en de professionals van druk gewerkt aan de lokale verkiezings- glashelder: “Het is tijd voor actie!” Liber gaat ductielid van harte welkom op bij- Bladmanagement: het Algemeen Secretariaat voor dat de programma’s. We merken dan ook hoe met haar in gesprek over het werven van nieu- voorbeeld onze congressen, bijeen- Debbie van de Wijngaard partij functioneert. -

The North Sea Agreement

The North Sea Agreement Going those extra miles for a healthy North Sea The North Sea Agreement Agreements between the Dutch government and stakeholders through to 2030 with a future vision on the development of wind energy in the long term. An accord was reached on this Agreement between the following participants in the North Sea Consultation (NZO): On behalf of the Dutch government: Cora van Nieuwenhuizen, Minister of Infrastructure and Water Management Carola Schouten, Minister of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality Eric Wiebes, Minister of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy On behalf of the energy organisations on the North Sea: Hans Timmers, chairman NWEA Jo Peters, Secretary-General NOGEPA Jan Willem van Hoogstraten, director EBN Marco Kuijpers, director offshore projects TenneT On behalf of the fishery organisations: Johan K. Nooitgedagt, chairman Nederlandse Vissersbond (Dutch Fishermen’s Association) approved the consultation agreement but following the agreed period of grassroots consultation informed the consultative body that the Dutch Fishermen’s Association could not support the agreement. Pim Visser, director of VisNed 1 (facilitating) indicated that the producers organisations Delta Zuid, Rousant, Redersvereniging voor de Zeevisserij (operators’ association for sea fishing), Texel, West and Wieringen and the Association of NetVISwerk support the Agreement. However, given the dissension within VisNed, they cannot sign. On behalf of the NGOs: Floris van Hest, director North Sea Foundation Kirsten Schuijt, director WWF Netherlands Joris Thijssen, director Greenpeace Rob van Tilburg, director of Programmes, Natuur en Milieu (Nature and Environment) Fred Wouters, director Vogelbescherming Nederland (Dutch Society for the Protection of Birds) Marc van den Tweel, Managing Director Natuurmonumenten (Dutch Society for the Preservation of Nature) 2 On behalf of the Sector Organisations for Seaports: Ronald Paul, chairman and COO port authority Havenbedrijf Rotterdam N.V. -

EUROPEAN UNION – the INSTITUTIONS Subject IAIN MCIVER Map

SPICe THE EUROPEAN UNION – THE INSTITUTIONS subject IAIN MCIVER map This subject map is one of four covering various aspects of the European Union. It provides information on the five institutions of the European 21 May 2007 Union. The institutions manage the way in which the EU functions and the way in which decisions are made. Scottish Parliament The other subject maps in this series are: 07/02 The European Union – A Brief History (07/01) The European Union – The Legislative Process (07/03) The European Union – The Budget (07/04) Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) Briefings are compiled for the benefit of the Members of the Parliament and their personal staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of these papers with MSPs and their staff who should contact Iain McIver on extension 85294 or email [email protected]. Members of the public or external organisations may comment on this briefing by emailing us at [email protected]. However, researchers are unable to enter into personal discussion in relation to SPICe Briefing Papers. If you have any general questions about the work of the Parliament you can email the Parliament’s Public Information Service at [email protected]. Every effort is made to ensure that the information contained in SPICe briefings is correct at the time of publication. Readers should be aware however that briefings are not necessarily updated or otherwise amended to reflect subsequent changes. www.scottish.parliament.uk 1 THE EU INSTITUTIONS The way the EU functions and the way decisions are made is determined by the institutions which have been established by the member states to run and oversee the EU. -

Lijst Van Gevallen En Tussentijds Vertrokken Wethouders Over De Periode 2002-2006, 2006-2010, 2010-2014, 2014-2018

Lijst van gevallen en tussentijds vertrokken wethouders Over de periode 2002-2006, 2006-2010, 2010-2014, 2014-2018 Inleiding De lijst van gevallen en tussentijds vertrokken wethouders verschijnt op de website van De Collegetafel als bijlage bij het boek Valkuilen voor wethouders, uitgegeven door Boombestuurskunde Den Haag. De lijst geeft een overzicht van alle gevallen en tussentijds vertrokken wethouders in de periode 2002 tot en met 2018. Deze lijst van gevallen en tussentijds vertrokken wethouders betreft de wethouders die vanwege een politieke vertrouwensbreuk tijdelijk en/of definitief ten val kwamen tijdens de collegeperiode (vanaf het aantreden van de wethouders na de collegevorming tot het einde van de collegeperiode) en van wethouders die om andere redenen tussentijds vertrokken of voor wie het wethouderschap eindigde voor het einde van de reguliere collegeperiode. De valpartijen van wethouders zijn in deze lijst benoemd als gevolg van een tijdelijke of definitieve politieke vertrouwensbreuk, uitgaande van het vertrekpunt dat een wethouder na zijn benoeming of wethouders na hun benoeming als lid van een college het vertrouwen heeft/hebben om volwaardig als wethouder te functioneren totdat hij/zij dat vertrouwen verliest dan wel het vertrouwen verliezen van de hen ondersteunende coalitiepartij(en). Of wethouders al dan niet gebruik hebben gemaakt van wachtgeld is geen criterium voor het opnemen van ten val gekomen wethouders in de onderhavige lijst. Patronen De cijfermatige conclusies en de geanalyseerde patronen in Valkuilen voor wethouders zijn gebaseerd op deze lijst van politiek (tijdelijk of definitief) gevallen en tussentijds vertrokken wethouders. De reden van het ten val komen of vertrek is in de lijst toegevoegd zodat te zien is welke bijvoorbeeld politieke valpartijen zijn. -

Top Margin 1

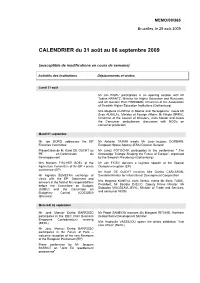

MEMO/09/365 Bruxelles, le 28 août 2009 CALENDRIER du 31 août au 06 septembre 2009 (susceptible de modifications en cours de semaine) Activités des Institutions Déplacements et visites Lundi 31 août Mr Ján FIGEL' participates in an opening session with Mr Tobias KRANTZ, Minister for Higher Education and Research, and Mr Sweden Pam FREDMAN, Chairman of the Association of Swedish Higher Education Institutions (Gothenburg) Mrs Meglena KUNEVA in Bosnia and Herzegovina: meets Mr Sven ALKALAJ, Minister of Foreign Affairs; Mr Nikola SPIRIC, Chairman of the Council of Ministers; visits Mostar and meets the Consumer ombudsman; discussion with NGOs on consumer protection Mardi 01 septembre Mr Joe BORG addresses the EP Mr Antonio TAJANI meets Mr Jean-Jacques DORDAIN, Fisheries Committee European Space Agency (ESA) Director General Présentation de M. Karel DE GUCHT au Mr Janez POTOČNIK participates in the conference " The PE en Commission du Knowledge Triangle Shaping the Future of Europe", organised Développement by the Swedish Presidency (Gothenburg) Mrs Mariann FISCHER BOEL at the Mr Ján FIGEL' delivers a keynote speech at the Special Agriculture Committee of the EP + press Olympics reception (EP) conference (EP) Mr Karel DE GUCHT receives Mrs Gunilla CARLSSON, Mr Algirdas ŠEMETA's exchange of Swedish Minister for International Development Cooperation views with the EP. Statement and answers in the field of his responsibilities Mrs Meglena KUNEVA visits Serbia: meets Mr Boris TADIC, before the Committee on Budgets President; Mr Bozidar DJELIC, -

Bijlagen VVD Bij Besluit Op Wob-Verzoek Over

Aan het ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken Postbus 2001 1 2500EA Den Haag Datum: 30juni2020 Betreft: Verantwoording t.b.v. WFPP 2019 Geachte heer, mevrouw, Bijgevoegd treft u de verantwoording aan over het jaar 2019, dit ten behoeve van de definitieve vaststelling van de subsidie. De verantwoording bestaat uit: - Financieel verslag over 2019 - Overzicht van giften van in totaal € 4.500 of hoger - Overzicht van schulden van € 25.000 of hoger - Schriftelijke verklaring van de accountant De bovengenoemde verantwoording is bijgevoegd voor de volgende organisaties: - Volkspartij voor vrijheid en Democratie (VVD) - Haya van Somerenstichting - Prof.mr. B.M. TeldersStichting - Jongerenorganisatie Vrijheid en Democratie (JOVD) Mr. S.J.A. ter Borg Directeur Vereniging “Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie” Mauritskade 21 2514 HD Den Haag tel. 070 - 361 30 61 Financieel jaarrapport 2019 &v. atiedoeIeinden Vereniging Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Oemocratie’, Den Haag Inhoudsopgave Voorwoord Pagina 2 Hoofdbestuursverslag Pagina 3 Hoofdbestuurssameristelllflg Pagina 5 3aarrekenlng Balans per 31 december 2019 Pagina 8 Staat van baten en lasten over 2019 Pagina 9 Algemene toelichting op de balans en staat van Pagina ii baten en lasten (inclusief organen) Bestemming van saldo baten en lasten Pagina 19 WO-organen Pagina 28 Overige gegevens Controleverklaring van de onafhankelijke accountant Pagina 30 Statutaire bepalingen Pagina 3 Sijlagen Staat van baten en lasten over 2019 van het Algemeen Secretariaat van de WO Pagina 33 Gehoorde neveninstehhingen Pagina 35 adoeleiriden Vereniging Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie”, Den Haag Voorwoord Dit jaarrapport geeft het overzicht van de financiële ontwikkelingen van de VVD In 2019. Er is in 2019 weer hard gewerkt om de VVD nog mooier te maken. -

Final Report of the Parliamentary Inquiry

Unprecedented injustice | House of Representatives of the States General Placeholder 35 510 Childcare Allowance Parliamentary Inquiry No. 2 LETTER FROM THE PARLIAMENTARY INQUIRY COMMITTEE To the Speaker of the House of Representatives of the States General The Hague, 17 December 2020 The Childcare Allowance Parliamentary Inquiry Committee on hereby presents its report entitled ‘Ongekend onrecht’ (‘Unprecedented injustice’) on the parliamentary inquiry that it carried out in accordance with the task assigned to it on 2 July 2020 (Parliamentary document 35 510, no. 1). The reports of the hearings that took place under oath are appended.1 Chairman of the Committee, Van Dam Clerk of the Committee, Freriks 1 Parliamentary document 35 510, no. 3. page 1/137 Unprecedented injustice | House of Representatives of the States General page 2/137 Unprecedented injustice | House of Representatives of the States General The members of the Childcare Allowance Parliamentary Inquiry Committee, from left to right: R.R. van Aalst, R.M. Leijten, S. Belhaj, C.J.L. van Dam, A.H. Kuiken, T.M.T. van der Lee, J. van Wijngaarden, and F.M. van Kooten-Arissen The members and the staff of the Childcare Allowance Parliamentary Inquiry Committee, from left to right: J.F.C. Freriks, R.M. Leijten, F.M. van Kooten-Arissen, R.J. de Bakker, C.J.L. van Dam, R.R. van Aalst, A.J. van Meeuwen, S. Belhaj, A.H. Kuiken, A.C. Verbruggen-Groot, T.M.T. van der Lee, J. van Wijngaarden, and M.C.C. van Haeften. W. Bernard-Kesting does not appear in the photograph. -

WRITTEN COMMENTS of the Bulgarian Helsinki Committee

WRITTEN COMMENTS Of the Bulgarian Helsinki Committee Concerning Bulgaria for Consideration by the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination at its 92nd Session March 2017 The Bulgarian Helsinki Committee (BHC) is an independent non-governmental organisation for the protection of human rights - political, civil, economic, social and cultural. It was established on 14 July 1992. The goal of the BHC is to promote respect and protection for the human rights of every individual, to advocate for legislative change to bring Bulgarian legislation in line with international standards, to encourage public debate on human rights issues, and to popularise and make widely known human rights instruments. The BHC is engaged in human rights monitoring, strategic litigation, advocacy, and human rights education. In its work, the BHC places special emphasis on discrimination, rights of ethnic and religious minorities, rights of the child, mental disability rights, conditions in places of detention, refugee and migrants rights, freedom of expression, access to information, problems of the criminal justice system. More information about the organisation and its publications are available online at http://www.bghelsinki.org. Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION 2 II. VIOLATIONS OF THE CONVENTION PROVISIONS, OMISSIONS AND MISREPRESENTATIONS IN THE GOVERNMENT REPORT 2 Article 2 2 1. Involvement of racist and xenophobic political parties in the government and exclusion of minorities 2 2. Acts and patterns of institutional racism in the framework of the criminal justice system and in migration 4 Article 4 7 1. Developments in 2013 8 2. Developments in 2014 11 3. Developments in 2015 13 4.