THE PHOTOGRAPHS of ESTHER BUBLEY Library of Congress, D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simone De Beauvoir's Photographic Journey Inspired by Her Diary, America Day by Day

Inspiration / Photography Simone de Beauvoir's photographic journey inspired by her diary, America Day by Day Written by Katy Cowan 22.01.2019 Esher Bubley, Coast to Coast, SONJ, 1947. @ Estate Esther Bubley / Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery / Sous Les Etoiles Gallery This month, Sous Les Etoiles Gallery in New York presents, 1947, Simone de Beauvoir in America, a photographic journey inspired by her diary, America Day by Day published in France in 1948. Curated by Corinne Tapia, director of the Gallery, the show aims to illustrate the depiction of De Beauvoir’s encounter with America at the time. In January of 1947, the French writer and intellectual, Simone de Beauvoir landed in New York’s La Guardia Airport, beginning a four-month journey across America. She travelled from East to the West coast by trains, cars and even Greyhound buses. She has recounted her travels in her personal diary and recorded every experience with minute detail. She stayed 116 days, travelling through 19 states and 56 cities. “The Second Sex”, published in 1949, became a reference in the feminist movement but has certainly masked the talent of diarist Simone de Beauvoir. The careful observer, endowed with a chiselled and precise writing style, travelling was central guidance of the existential experience for her, a woman with infinite curiosity, a thirst for experiencing and discovering everything. In 1929, she made her first trips to Spain, Italy and England with her lifelong partner, the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. In 1947, she made, this time alone, her first trip to the United States, a trip that would have changed her life: "Usually, travelling is an attempt to annex a new object to my universe; this in itself is an undertaking: but today it’s different. -

Oral History Interview with Roy Emerson Stryker, 1963-1965

Oral history interview with Roy Emerson Stryker, 1963-1965 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Roy Stryker on October 17, 1963. The interview took place in Montrose, Colorado, and was conducted by Richard Doud for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview Side 1 RICHARD DOUD: Mr. Stryker, we were discussing Tugwell and the organization of the FSA Photography Project. Would you care to go into a little detail on what Tugwell had in mind with this thing? ROY STRYKER: First, I think I'll have to raise a certain question about your emphasis on the word "Photography Project." During the course of the morning I gave you a copy of my job description. It might be interesting to refer back to it before we get through. RICHARD DOUD: Very well. ROY STRYKER: I was Chief of the Historical Section, in the Division of Information. My job was to collect documents and materials that might have some bearing, later, on the history of the Farm Security Administration. I don't want to say that photography wasn't conceived and thought of by Mr. Tugwell, because my backround -- as we'll have reason to talk about later -- and my work at Columbia was very heavily involved in the visual. -

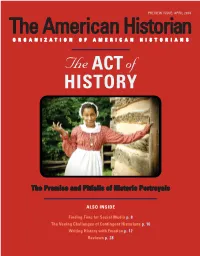

Preview Issue, the American Historian

PREVIEW ISSUE: APRIL 2014 The American Historian ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN HISTORIANS The ACT of HISTORY The Promise and Pitfalls of Historic Portrayals ALSO INSIDE Finding Time for Social Media p. 8 The Vexing Challenges of Contingent Historians p. 10 Writing History with Emotion p. 12 Reviews p. 28 Career and family... We’ve got you covered. Organization of American Historians’ member insurance plans and services have been carefully chosen for their valuable benefits at competitive group rates from a variety of reputable, highly-rated carriers. Professional Home & Auto • Professional Liability • GEICO Automobile Insurance • Private Practice Professional Liability • Homeowners Insurance • Student Educator Professional Liability • Pet Health Insurance Health Life • TIE Health Insurance Exchange • New York Life Group Term • New York Life Group Accidental Death Life Insurance† & Dismemberment Insurance† • New York Life 10 Year Level • Cancer Insurance Plan Group Term Life Insurance† • Medicare Supplement Insurance • Educators Dental Plan † Underwritten by New York Life Insurance Company, New York, NY 10010 Policy Form GMR. Please note: Not all plans are available in all states. Trust for Insuring Educators Administered by Forrest T. Jones & Company (800) 821-7303 • www.ftj.com/OAH Personalized Long Term Care Insurance Evaluation Featuring top insurance companies and special discounts. This advertisement is for informational purposes only and is not meant to define, alter, limit or expand any policy in any way. For a descriptive brochure that summarizes features, costs, eligibility, renewability, limitations and exclusions, call Forrest T. Jones & Company. Arkansas producer license #71740, California producer license #0592939. 2 The American Historian | April 2014 #6608 0314 6608 OAH All Coverage Ad.indd 1 2/26/14 3:46 PM Career and family.. -

1937-1943 Additional Excerpts

Wright State University CORE Scholar Books Authored by Wright State Faculty/Staff 1997 The Celebrative Spirit: 1937-1943 Additional Excerpts Ronald R. Geibert Wright State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/books Part of the Photography Commons Repository Citation Geibert , R. R. (1997). The Celebrative Spirit: 1937-1943 Additional Excerpts. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books Authored by Wright State Faculty/Staff by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Additional excerpts from the 1997 CD-ROM and 1986 exhibition The Celebrative Spirit: 1937-1943 John Collier’s work as a visual anthropologist has roots in his early years growing up in Taos, New Mexico, where his father was head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. His interest in Native Americans of the Southwest would prove to be a source of conflict with his future boss, Roy Stryker, director of the FSA photography project. A westerner from Colorado, Stryker did not consider Indians to be part of the mission of the FSA. Perhaps he worried about perceived encroachment by the FSA on BIA turf. Whatever the reason, the rancor of his complaints when Collier insisted on spending a few extra weeks in the West photographing native villages indicates Stryker may have harbored at least a smattering of the old western anti-Indian attitude. By contrast, Collier’s work with Mexican Americans was a welcome and encouraged addition to the FSA file. -

Documenting the Dissin's Guest House: Esther Bubley's Exploration of Jewish-American Identity, 1942-43

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2013-06-03 Documenting the Dissin's Guest House: Esther Bubley's Exploration of Jewish-American Identity, 1942-43 Vriean Diether Taggart Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Taggart, Vriean Diether, "Documenting the Dissin's Guest House: Esther Bubley's Exploration of Jewish- American Identity, 1942-43" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 3599. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/3599 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Documenting the Dissin’s Guest House: Esther Bubley’s Exploration of Jewish- American Identity, 1942-43 Vriean 'Breezy' Diether Taggart A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts James Russel Swensen, Chair Marian E. Wardle Heather Jensen Department of Visual Arts Brigham Young University May 2013 Copyright © 2013 Vriean 'Breezy' Diether Taggart All rights reserved ABSTRACT Documenting the Dissin’s Guest House: Esther Bubley’s Exploration of Jewish- American Identity, 1942-43 Vriean 'Breezy' Diether Taggart Department of Visual Arts Master of Arts This thesis considers Esther Bubley’s photographic documentation of a boarding house for Jewish workingmen and women during World War II. An examination of Bubley’s photographs reveals the complexities surrounding Jewish-American identity, which included aspects of social inclusion and exclusion, a rejection of past traditions and acceptance of contemporary transitions. -

Fall 2018 Alumni Magazine

University Advancement NONPROFIT ORG PO Box 2000 U.S. POSTAGE Superior, Wisconsin 54880-4500 PAID DULUTH, MN Travel with Alumni and Friends! PERMIT NO. 1003 Rediscover Cuba: A Cultural Exploration If this issue is addressed to an individual who no longer uses this as a permanent address, please notify the Alumni Office at February 20-27, 2019 UW-Superior of the correct mailing address – 715-394-8452 or Join us as we cross a cultural divide, exploring the art, history and culture of the Cuban people. Develop an understanding [email protected]. of who they are when meeting with local shop keepers, musicians, choral singers, dancers, factory workers and more. Discover Cuba’s history visiting its historic cathedrals and colonial homes on city tours with your local guide, and experience one of the world’s most culturally rich cities, Havana, and explore much of the city’s unique architecture. Throughout your journey, experience the power of travel to unite two peoples in a true cultural exchange. Canadian Rockies by Train September 15-22, 2019 Discover the western Canadian coast and the natural beauty of the Canadian Rockies on a tour featuring VIA Rail's overnight train journey. Begin your journey in cosmopolitan Calgary, then discover the natural beauty of Lake Louise, Moraine Lake, and the powerful Bow Falls and the impressive Hoodoos. Feel like royalty at the grand Fairmont Banff Springs, known as the “Castle in the Rockies,” where you’ll enjoy a luxurious two-night stay in Banff. Journey along the unforgettable Icefields Parkway, with a stop at Athabasca Glacier and Peyto Lake – a turquoise glacier-fed treasure that evokes pure serenity – before arriving in Jasper, nestled in the heart of the Canadian Rockies. -

FSA Photographers in Indiana

Websites about FSA Photographers in Indiana Esther Bubley Carnegie Library of Philadelphia: The Photographers http://www.clpgh.org/exhibit/photog6.html Esther Bubley, Photojournalist. http://estherbubley.com/ Women Come to the Front: Journalists, Photographers and Broadcasters during WWII: Esther Bubley http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/wcf/wcf0012.html Women Photojournalists: Esther Bubley http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/coll/womphotoj/bubleyintro.html Paul Carter The Carters of Yorkshire: As they relate to "The Rectory Family" and beyond http://www.cartertools.com/cartyork.html Jack Delano Center for Railroad Art and Photograph http://www.railphoto-art.org/galleries/delano.html Chicago Rail Photographs of Jack Delano: Chicago Reader http://www.chicagoreader.com/TheBlog/archives/2010/09/03/the-chicago-rail-photographs-of- jack-delano Jack Delano at the Museum of Contemporary Photography http://www.mocp.org/collections/permanent/delano_jack.php Smithsonian Archives of American Art: Interview with Jack Delano http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/oralhistories/transcripts/delano65.htm Indiana Farm Security Administration Photographs Digital Collection http://www.ulib.iupui.edu/IFSAP FSA Photographers in Indiana - 2 Theodor Jung Theodor Jung Photo Collection http://www.shorpy.com/image/tid/124 Dorothea Lange America’s Stories from America’s Library: Dorothea Lange http://www.americaslibrary.gov/aa/lange/aa_lange_subj.html The Art Department of the Oakland Museum of California Dorothea Lange Collection: http://www.museumca.org/global/art/collections_dorothea_lange.html -

Silver Eye 2018 Auction Catalog

Silver Eye Benefit Auction Guide 18A Contents Welcome 3 Committees & Sponsors 4 Acknowledgments 5 A Note About the Lab 6 Lot Notations 7 Conditions of Sale 8 Auction Lots 10 Glossary 93 Auction Calendar 94 B Cover image: Gregory Halpern, Untitled 1 Welcome Silver Eye 5.19.18 11–2pm Benefit Auction 4808 Penn Ave Pittsburgh, PA AUCTIONEER Welcome to Silver Eye Center for Photography’s 2018 Alison Brand Oehler biennial Auction, one of our largest and most important Director of Concept Art fundraisers. Proceeds from the Auction support Gallery, Pittsburgh exhibitions and artists, and keep our gallery and program admission free. When you place a bid at the Auction, TICKETS: $75 you are helping to create a future for Silver Eye that Admission can be keeps compelling, thoughtful, beautiful, and challenging purchased online: art in our community. silvereye.org/auction2018 The photographs in this catalog represent the most talented, ABSENTEE BIDS generous, and creative artists working in photography today. Available on our website: They have been gathered together over a period of years silvereye.org/auction2018 and represent one of the most exciting exhibitions held on the premises of Silver Eye. As an organization, we are dedicated to the understanding, appreciation, education, and promotion of photography as art. No exhibition allows us to share the breadth and depth of our program as well as the Auction Preview Exhibition. We are profoundly grateful to those who believe in us and support what we bring to the field of photography. Silver Eye is generously supported by the Allegheny Regional Asset District, Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, The Heinz Endowments, The Pittsburgh Foundation, The Fine Foundation, The Jack Buncher Foundation, The Joy of Giving Something Foundation, The Hillman Foundation, an anonymous donor, other foundations, and our members. -

Farm Security Administation Photographs in Indiana

FARM SECURITY ADMINISTRATION PHOTOGRAPHS IN INDIANA A STUDY GUIDE Roy Stryker Told the FSA Photographers “Show the city people what it is like to live on the farm.” TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 The FSA - OWI Photographic Collection at the Library of Congress 1 Great Depression and Farms 1 Roosevelt and Rural America 2 Creation of the Resettlement Administration 3 Creation of the Farm Security Administration 3 Organization of the FSA 5 Historical Section of the FSA 5 Criticisms of the FSA 8 The Indiana FSA Photographers 10 The Indiana FSA Photographs 13 City and Town 14 Erosion of the Land 16 River Floods 16 Tenant Farmers 18 Wartime Stories 19 New Deal Communities 19 Photographing Indiana Communities 22 Decatur Homesteads 23 Wabash Farms 23 Deshee Farms 24 Ideal of Agrarian Life 26 Faces and Character 27 Women, Work and the Hearth 28 Houses and Farm Buildings 29 Leisure and Relaxation Activities 30 Afro-Americans 30 The Changing Face of Rural America 31 Introduction This study guide is meant to provide an overall history of the Farm Security Administration and its photographic project in Indiana. It also provides background information, which can be used by students as they carry out the curriculum activities. Along with the curriculum resources, the study guide provides a basis for studying the history of the photos taken in Indiana by the FSA photographers. The FSA - OWI Photographic Collection at the Library of Congress The photographs of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) - Office of War Information (OWI) Photograph Collection at the Library of Congress form a large-scale photographic record of American life between 1935 and 1944. -

FY 15 ANNUAL REPORT August 1, 2014- July 31, 2015

FY 15 ANNUAL REPORT August 1, 2014- July 31, 2015 1 THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION FY15 Annual Report THE PHILLIPS [IS] A MULTIDIMENSIONAL INSTITUTION THAT CRAVES COLOR, CONNECTEDNESS, A PIONEERING SPIRIT, AND PERSONAL EXPERIENCES 2 THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION FY15 Annual Report FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND DIRECTOR This is an incredibly exciting time to be involved with The Phillips Collection. Duncan Phillips had a deep understanding of the “joy-giving, life-enhancing influence” of art, and this connection between art and well-being has always been a driving force. Over the past year, we have continued to push boundaries and forge new paths with that sentiment in mind, from our art acquisitions to our engaging educational programming. Our colorful new visual identity—launched in fall 2014—grew out of the idea of the Phillips as a multidimensional institution, a museum that craves color, connectedness, a pioneering spirit, and personal experiences. Our programming continues to deepen personal conversations with works of art. Art and Wellness: Creative Aging, our collaboration with Iona Senior Services has continued to help participants engage personal memories through conversations and the creating of art. Similarly, our award-winning Contemplation Audio Tour encourages visitors to harness the restorative power of art by deepening their relationship with the art on view. With Duncan Phillips’s philosophies leading the way, we have significantly expanded the collection. The promised gift of 18 American sculptors’ drawings from Trustee Linda Lichtenberg Kaplan, along with the gift of 46 major works by contemporary German and Danish artists from Michael Werner, add significantly to new possibilities that further Phillips’s vision of vital “creative conversations” in our intimate galleries. -

The Bitter Years: 1935-1941 Rural America As Seen by the Photographers of the Farm Security Administration

The bitter years: 1935-1941 Rural America as seen by the photographers of the Farm Security Administration. Edited by Edward Steichen Author United States. Farm Security Administration Date 1962 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art: Distributed by Doubleday, Garden City, N.Y. Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3433 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history—from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art THE BITTER YEARS 1.935-1 94 1 Rural America as seen by the photographers of the Farm Security Administration Edited by Edward Steichen The Museum of Modern Art New York The Bitter Years: 1935-1941 Rural America as seen by the photographers of the Farm Security Administration Edited by Edward Steichen The Museum of Modern Art, New Y ork Distributed by Doubleday and Co., Inc., Garden City, N.5 . To salute one of the proudest achievements in the history of photography, this book and the exhibition on which it is based are dedicated by Edward Steichen to ROY E. STRYKER who organized and directed the Photographic Unit of the Farm Security Administration and to his photo graphers : Paul Carter, John Collier, Jr., Jack Delano, Walker Evans, Theo Jung, Dorothea Lange, Russell Lee, Carl Mydans, Arthur Rothstein, Ben Shahn, John Vachon, and Marion Post Wolcott. © 1962, The Museumof Modern Art, JVew York Library of CongressCatalogue Card JVumber:62-22096 Printed in the United States of America I believe it is good at this time to be reminded of It was clear to those of us who had responsibility for those "Bitter Years" and to bring them into the con the relief of distress among farmers during the Great sciousness of a new generation which has problems of Depression and during the following years of drought, its own, but is largely unaware of the endurance and that we were passing through an experience of fortitude that made the emergence from the Great American life that was unique. -

Sorrow-Hope Guide to Names.Pdf

Times of Sorrow & Hope GUIDE TO PERSONAL NAMES IN THE ON-LINE CATALOG This section is a guide to individuals and Ballman, George C. Merritt Bundy family families whose images are captured in these Ephrata, November . Du Bois and Penfield, photographs and who are named in the titles Marjory Collins. September . Jack Delano. given to the photographs. These people may Banonis, Al Bushong, O. K. not necessarily come from the places men- Shenandoah, [?]. Sheldon Dick. Lititz, November . tioned in the titles: the photographs were Beck brothers Marjory Collins. taken during the WWII years, and some Lititz, May . Sheldon Dick. Butkeraits, Jacob people were working elsewhere in Penn- Walter Bennett’s mill Pittsburgh, June . Marjory Collins. sylvania or were in the armed forces. But it Chaneysville, December . would appear that for the most part, the Arthur Rothstein. C people pictured do come from the areas men- Bernicoff, Clarence Carlotta, Bertha tioned. (Many more fsa-owi photographs Allentown, between and [?]. Pitcairn, May . Marjory Collins. include people, but no personal names U.S. Army photograph. [Note: See Carson, Clem (“Bud”) appear in the titles.) “Other and Unidentified Photographs” Pittsburgh, September . section of the catalog.] Esther Bubley. A Bert, Henry Casey, Jean Ackerman, Milton B. Sharon, February . Philadelphia, June . Jack Delano. Erie, June–July . Alfred Palmer. Chiaco, Frank Alfred Palmer and John Vachon. Biggs, E. Power Pennsylvania [no specific place indi- Almoney family Bethlehem, May . cated]. [Note: Photograph taken in Lititz, November . Howard Hollem. Hawaii. See “Other and Unidentified Marjory Collins. Boatman, Charles Photographs” section of the catalog.] Ankrom, Mary Pennsylvania Emergency Pipeline, Choly, William Pitcairn, May .