ARTISTS WHO HAD CANCER Works from the Hillstrom and Shogren-Meyer Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simone De Beauvoir's Photographic Journey Inspired by Her Diary, America Day by Day

Inspiration / Photography Simone de Beauvoir's photographic journey inspired by her diary, America Day by Day Written by Katy Cowan 22.01.2019 Esher Bubley, Coast to Coast, SONJ, 1947. @ Estate Esther Bubley / Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery / Sous Les Etoiles Gallery This month, Sous Les Etoiles Gallery in New York presents, 1947, Simone de Beauvoir in America, a photographic journey inspired by her diary, America Day by Day published in France in 1948. Curated by Corinne Tapia, director of the Gallery, the show aims to illustrate the depiction of De Beauvoir’s encounter with America at the time. In January of 1947, the French writer and intellectual, Simone de Beauvoir landed in New York’s La Guardia Airport, beginning a four-month journey across America. She travelled from East to the West coast by trains, cars and even Greyhound buses. She has recounted her travels in her personal diary and recorded every experience with minute detail. She stayed 116 days, travelling through 19 states and 56 cities. “The Second Sex”, published in 1949, became a reference in the feminist movement but has certainly masked the talent of diarist Simone de Beauvoir. The careful observer, endowed with a chiselled and precise writing style, travelling was central guidance of the existential experience for her, a woman with infinite curiosity, a thirst for experiencing and discovering everything. In 1929, she made her first trips to Spain, Italy and England with her lifelong partner, the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. In 1947, she made, this time alone, her first trip to the United States, a trip that would have changed her life: "Usually, travelling is an attempt to annex a new object to my universe; this in itself is an undertaking: but today it’s different. -

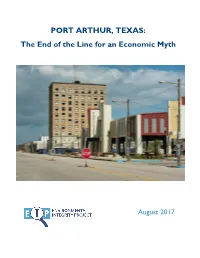

PORT ARTHUR, TEXAS: the End of the Line for an Economic Myth

PORT ARTHUR, TEXAS: The End of the Line for an Economic Myth August 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was researched and written by Mary Greene and Keene Kelderman of the Environmental Integrity Project. THE ENVIRONMENTAL INTEGRITY PROJECT The Environmental Integrity Project (http://www.environmentalintegrity.org) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization established in March of 2002 by former EPA enforcement attorneys to advocate for effective enforcement of environmental laws. EIP has three goals: 1) to provide objective analyses of how the failure to enforce or implement environmental laws increases pollution and affects public health; 2) to hold federal and state agencies, as well as individual corporations, accountable for failing to enforce or comply with environmental laws; and 3) to help local communities obtain the protection of environmental laws. For questions about this report, please contact EIP Director of Communications Tom Pelton at (202) 888-2703 or [email protected]. PHOTO CREDITS Cover photo by Garth Lenz of Port Arthur. Executive Summary The Trump Administration’s approval of the Keystone XL Pipeline will lead to a surge in demand for oil refining at the southern end of the line, in Port Arthur, Texas – and a real test for claims that the administration’s promotion of fossil fuel industries will create jobs. The industrial port of 55,000 people on the Gulf of Mexico has been the home of America’s largest concentration of oil refineries for decades, and business has been booming. But history has shown little connection between the profitability of the petrochemical industries that dominate Port Arthur and the employment or health of the local people who live in this city of increasingly abandoned buildings and empty lots. -

Oral History Interview with Frederick A. Sweet, 1976 February 13-14

Oral history interview with Frederick A. Sweet, 1976 February 13-14 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Frederick Sweet on February 13 & 14, 1976. The interview took place in Sargentville, Maine, and was conducted by Robert Brown for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview February 13, 1976. ROBERT BROWN: Could you begin, perhaps, by just sketching out a bit of your childhood, and we can pick up from there. FREDERICK SWEET: I spent most of my early childhood in this house. My father, a doctor and tenth generation Rhode Islander, went out to Bisbee, Arizona, a wild-west copper-mining town, as the chief surgeon under the aegis of the Company. My mother always came East at pregnancy and was in New York visiting relatives when my father died very suddenly of cerebral hemorrhage. My mother was seven months pregnant with me. Since I was to be a summer baby, she ended up by coming to this house and being a cook and being a cook and a nurse with her there. The local doctor came and said nothing was going to happen for quite a long time and went off in his horse and buggy. I was promptly delivered by the cook and a nurse. -

Oral History Interview with Roy Emerson Stryker, 1963-1965

Oral history interview with Roy Emerson Stryker, 1963-1965 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Roy Stryker on October 17, 1963. The interview took place in Montrose, Colorado, and was conducted by Richard Doud for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview Side 1 RICHARD DOUD: Mr. Stryker, we were discussing Tugwell and the organization of the FSA Photography Project. Would you care to go into a little detail on what Tugwell had in mind with this thing? ROY STRYKER: First, I think I'll have to raise a certain question about your emphasis on the word "Photography Project." During the course of the morning I gave you a copy of my job description. It might be interesting to refer back to it before we get through. RICHARD DOUD: Very well. ROY STRYKER: I was Chief of the Historical Section, in the Division of Information. My job was to collect documents and materials that might have some bearing, later, on the history of the Farm Security Administration. I don't want to say that photography wasn't conceived and thought of by Mr. Tugwell, because my backround -- as we'll have reason to talk about later -- and my work at Columbia was very heavily involved in the visual. -

Preview Issue, the American Historian

PREVIEW ISSUE: APRIL 2014 The American Historian ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN HISTORIANS The ACT of HISTORY The Promise and Pitfalls of Historic Portrayals ALSO INSIDE Finding Time for Social Media p. 8 The Vexing Challenges of Contingent Historians p. 10 Writing History with Emotion p. 12 Reviews p. 28 Career and family... We’ve got you covered. Organization of American Historians’ member insurance plans and services have been carefully chosen for their valuable benefits at competitive group rates from a variety of reputable, highly-rated carriers. Professional Home & Auto • Professional Liability • GEICO Automobile Insurance • Private Practice Professional Liability • Homeowners Insurance • Student Educator Professional Liability • Pet Health Insurance Health Life • TIE Health Insurance Exchange • New York Life Group Term • New York Life Group Accidental Death Life Insurance† & Dismemberment Insurance† • New York Life 10 Year Level • Cancer Insurance Plan Group Term Life Insurance† • Medicare Supplement Insurance • Educators Dental Plan † Underwritten by New York Life Insurance Company, New York, NY 10010 Policy Form GMR. Please note: Not all plans are available in all states. Trust for Insuring Educators Administered by Forrest T. Jones & Company (800) 821-7303 • www.ftj.com/OAH Personalized Long Term Care Insurance Evaluation Featuring top insurance companies and special discounts. This advertisement is for informational purposes only and is not meant to define, alter, limit or expand any policy in any way. For a descriptive brochure that summarizes features, costs, eligibility, renewability, limitations and exclusions, call Forrest T. Jones & Company. Arkansas producer license #71740, California producer license #0592939. 2 The American Historian | April 2014 #6608 0314 6608 OAH All Coverage Ad.indd 1 2/26/14 3:46 PM Career and family.. -

Arthurs Eyes Free

FREE ARTHURS EYES PDF Marc Brown | 32 pages | 03 Apr 2008 | Little, Brown & Company | 9780316110693 | English | New York, United States Arthurs Eyes | Elwood City Wiki | Fandom The episode begins with four LeVars looking at seeing riddles in different ways. With one picture, the first one sees it as spots on a giraffe. The second one sees it as eyes and a nose when you turn it around at 90 degrees. The third one sees it as a close-up of Swiss cheese. The fourth one sees it as two balloons playing catch. It all depends on how you look at it. The four LeVars look at a couple more eye riddles. Many people see many things in different ways. Besides having a unique way of seeing things, people's other senses are unique too. LeVar loves coming Arthurs Eyes the farmer's bazaar because he gets surrounded by all kinds of sights, smells, and textures. He challenges the viewers' eyes at seeing Arthurs Eyes of certain fruits and vegetables. The things the viewers see are viewed through a special camera lens. Some people use special lenses to see things, especially when they can't see well. LeVar explains, "I wear glasses, and sometimes I wear contact lenses. A different color blindness, unlike with your eyes, has something to do with your mind. It has nothing to do with what you see, but how you see it. LeVar has a flipbook he made himself. The picture changes each time you turn a page. Flipping the pages faster looks like a moving film. -

Documenting the Dissin's Guest House: Esther Bubley's Exploration of Jewish-American Identity, 1942-43

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2013-06-03 Documenting the Dissin's Guest House: Esther Bubley's Exploration of Jewish-American Identity, 1942-43 Vriean Diether Taggart Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Taggart, Vriean Diether, "Documenting the Dissin's Guest House: Esther Bubley's Exploration of Jewish- American Identity, 1942-43" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 3599. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/3599 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Documenting the Dissin’s Guest House: Esther Bubley’s Exploration of Jewish- American Identity, 1942-43 Vriean 'Breezy' Diether Taggart A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts James Russel Swensen, Chair Marian E. Wardle Heather Jensen Department of Visual Arts Brigham Young University May 2013 Copyright © 2013 Vriean 'Breezy' Diether Taggart All rights reserved ABSTRACT Documenting the Dissin’s Guest House: Esther Bubley’s Exploration of Jewish- American Identity, 1942-43 Vriean 'Breezy' Diether Taggart Department of Visual Arts Master of Arts This thesis considers Esther Bubley’s photographic documentation of a boarding house for Jewish workingmen and women during World War II. An examination of Bubley’s photographs reveals the complexities surrounding Jewish-American identity, which included aspects of social inclusion and exclusion, a rejection of past traditions and acceptance of contemporary transitions. -

Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected]

1 Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected] Education Feb. 1973 PhD., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Thesis: "The Genre Painting of Eastman Johnson: The Sources and Development of His Style and Themes," (Published by Garland, 1977). Adviser: Professor Robert Goldwater. Jan. 1968 M.A., Hunter College, City University of New York. Thesis: "The Portraits of Thomas Eakins: The Elements of Interpretation." Adviser: Professor Leo Steinberg. June 1957 B.A., Stanford University. Major: Modern European Literature Professional Positions 9/1978 – 7/2014 Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University: Acting Chair, Spring 2009; Spring 2012. Chair, 1995-97; Professor 1988-2014; Associate Professor, 1978-88 [retired 2014] Other assignments: Adviser to Graduate Students, Boston University Art Gallery, 2010-2011; Director of Graduate Studies, 1993-94; Director, BU Art Gallery, 1980-89; Director, Museum Studies Program, 1980-91 Affiliated Faculty Member: American and New England Studies Program; African American Studies Program April-July 2013 Terra Foundation Visiting Professor, J. F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies, Freie Universität, Berlin 9/74 - 7/87 Adjunct Curator, 18th- & 19th-C Art, Whitney Museum of Am. Art, NY 6/81 C. V. Whitney Lectureship, Summer Institute of Western American Studies, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming 9/74 - 8/78 Asso. Prof., Fine Arts/Performing Arts, York College, City University of New York, Queens, and PhD Program in Art History, Graduate Center. 1-6/75 Adjunct Asso. Prof. Grad. School of Arts & Science, Columbia Univ. 1/72-9/74 Asso. -

Prints by Raphael Soyer

Prints by Raphael Soyer from the Collection of the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester January 25 – April 22, 2012 right: Self-Portrait, 1963 Etching The Charles Rand Penney Collection of the Memorial Art Gallery, 75.304 below: Self-Portrait, 1967 Lithograph Gift of Diane Ambler, UR Class of 1971, and Ethan Grossman, 2011.48 right: Self Portrait (Know Thyself), 1982 Lithograph Gift of Diane Ambler, UR Class of 1971, and Ethan Grossman, 2011.50 Funds for this brochure were generously provided by Diane Ambler and Ethan Grossman. To learn more about works of art in the Gallery’s collection, school programs, and upcoming exhibitions and events, visit our website: mag.rochester.edu Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester 500 University Avenue Rochester, NY 14607 585.276.8900 Prints by Raphael Soyer January 25 – April 22, 2012 from the Collection of the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester A prolific realist painter and printmaker, Raphael Soyer had a career that spanned most of the twentieth century with its various artistic ‘isms.’ New York was his first and only American home, to which he immigrated from Russia in 1912, and it became his muse: “I painted only what I saw in my neighborhood in New York City which I call my country…New York and I are a part of one another.” Soyer studied at Cooper Union’s night school, the National Academy of Design, and the Art Students League while he worked at a variety of day jobs to earn money for himself and his family. -

Fall 2018 Alumni Magazine

University Advancement NONPROFIT ORG PO Box 2000 U.S. POSTAGE Superior, Wisconsin 54880-4500 PAID DULUTH, MN Travel with Alumni and Friends! PERMIT NO. 1003 Rediscover Cuba: A Cultural Exploration If this issue is addressed to an individual who no longer uses this as a permanent address, please notify the Alumni Office at February 20-27, 2019 UW-Superior of the correct mailing address – 715-394-8452 or Join us as we cross a cultural divide, exploring the art, history and culture of the Cuban people. Develop an understanding [email protected]. of who they are when meeting with local shop keepers, musicians, choral singers, dancers, factory workers and more. Discover Cuba’s history visiting its historic cathedrals and colonial homes on city tours with your local guide, and experience one of the world’s most culturally rich cities, Havana, and explore much of the city’s unique architecture. Throughout your journey, experience the power of travel to unite two peoples in a true cultural exchange. Canadian Rockies by Train September 15-22, 2019 Discover the western Canadian coast and the natural beauty of the Canadian Rockies on a tour featuring VIA Rail's overnight train journey. Begin your journey in cosmopolitan Calgary, then discover the natural beauty of Lake Louise, Moraine Lake, and the powerful Bow Falls and the impressive Hoodoos. Feel like royalty at the grand Fairmont Banff Springs, known as the “Castle in the Rockies,” where you’ll enjoy a luxurious two-night stay in Banff. Journey along the unforgettable Icefields Parkway, with a stop at Athabasca Glacier and Peyto Lake – a turquoise glacier-fed treasure that evokes pure serenity – before arriving in Jasper, nestled in the heart of the Canadian Rockies. -

Class Actions: an Interview with Arthur Miller by Rachel V

Corporate and Association Counsel Division Class Actions: An Interview with Arthur Miller by Rachel V. Rose Arthur R. Miller CBE, LL.B., is a professor at the New York University School of Law, associate dean of the NYU School of Professional Studies, direc- tor of the Tisch Sports Institute, chairman of the NYU Sports & Society Program, and former Bruce Bromley Professor of Law at Harvard Law School (1971–2007). He is on the faculties at the universi- ties of Minnesota and Michigan and practiced law Rachel V. Rose, J.D., MBA, is the chair of the in New York City. His undergraduate degree is from FBA’s Corporate and the University of Rochester, and his juris doctor is Associations Counsel from Harvard Law School. He has hosted “Miller’s Division and is on Court” for eight years, is a former legal commentator the FBA Government for Boston’s WCVB-TV, legal editor for ABC’s “Good Relations Committee. Rose is co-author of What Morning America,” and host of “Miller Law” on Are International HIPAA Court TV. He is the author or co-author of numerous Considerations? and The works on civil procedure, notably the Wright & Miller ABCs of ACOs. She can treatise, Federal Practice & Procedure. He has also be reached at rvrose@ written on copyright and on privacy issues. Miller rvrose.com. © 2015 Rachel V. Rose. All carries on an active law practice, particularly in the which is one of the reasons that I think that they rights reserved. federal appellate courts. exercise restraint—they know they are not experts in procedure. -

Ivan Albright's Ida and the "Object Congealed Around a Soul"

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Faculty and Staff Publications By Year Faculty and Staff Publications Fall 2015 Ivan Albright's Ida and the "Object Congealed Around a Soul" Elizabeth Lee Dickinson College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.dickinson.edu/faculty_publications Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Elizabeth. "Ivan Albright's Ida and the "Object Congealed Around a Soul."' American Art 29, no. 3 (2015): 104-117. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/684922# This article is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ivan Albright’s Ida and the “Object Congealed around a Soul” Elizabeth Lee For some time now I haven’t painted pictures, per se. I make statements, ask questions, search for principles. The paint and brushes are but mere extensions of myself or scalpels if you wish. —Ivan Albright1 From the start of his career in the late 1920s, the Chicago-born painter Ivan Albright was praised by critics for his precise, meticulous forms and yet also reviled for his off- putting approach to the human figure. The Lineman(fig. 1), for example, which won the John C. Shaffer Prize for portraiture at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1928, sparked concern when it appeared on the cover of the trade magazine Electric Light and Power. A. B. Gates, a manager from the Edison Company, protested the lineman’s appearance as a “stoop-shouldered individual exuding an atmosphere of hopelessness and dejection,” explaining that the image failed to capture the strong, youthful stature of the typical modern American workman.2 Subsequent paintings from this period were not merely offensive; they were utterly revolting, as the artist approached his subjects with increasingly clinical detail.