"Introducing America to Americans": FSA Photography and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pressemappe American Photography

Exhibition Facts Duration 24 August – 28 November 2021 Virtual Opening 23. August 2021 | 6.30 PM | on Facebook-Live & YouTube Venue Bastion Hall Curator Walter Moser Co-Curator Anna Hanreich Works ca. 180 Catalogue Available for EUR EUR 29,90 (English & German) onsite at the Museum Shop as well as via www.albertina.at Contact Albertinaplatz 1 | 1010 Vienna T +43 (01) 534 83 0 [email protected] www.albertina.at Opening Hours Daily 10 am – 6 pm Press contact Daniel Benyes T +43 (01) 534 83 511 | M +43 (0)699 12178720 [email protected] Sarah Wulbrandt T +43 (01) 534 83 512 | M +43 (0)699 10981743 [email protected] 2 American Photography 24 August - 28 November 2021 The exhibition American Photography presents an overview of the development of US American photography between the 1930s and the 2000s. With works by 33 artists on display, it introduces the essential currents that once revolutionized the canon of classic motifs and photographic practices. The effects of this have reached far beyond the country’s borders to the present day. The main focus of the works is on offering a visual survey of the United States by depicting its people and their living environments. A microcosm frequently viewed through the lens of everyday occurrences permits us to draw conclusions about the prevalent political circumstances and social conditions in the United States, capturing the country and its inhabitants in their idiosyncrasies and contradictions. In several instances, artists having immigrated from Europe successfully perceived hitherto unknown aspects through their eyes as outsiders, thus providing new impulses. -

Simone De Beauvoir's Photographic Journey Inspired by Her Diary, America Day by Day

Inspiration / Photography Simone de Beauvoir's photographic journey inspired by her diary, America Day by Day Written by Katy Cowan 22.01.2019 Esher Bubley, Coast to Coast, SONJ, 1947. @ Estate Esther Bubley / Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery / Sous Les Etoiles Gallery This month, Sous Les Etoiles Gallery in New York presents, 1947, Simone de Beauvoir in America, a photographic journey inspired by her diary, America Day by Day published in France in 1948. Curated by Corinne Tapia, director of the Gallery, the show aims to illustrate the depiction of De Beauvoir’s encounter with America at the time. In January of 1947, the French writer and intellectual, Simone de Beauvoir landed in New York’s La Guardia Airport, beginning a four-month journey across America. She travelled from East to the West coast by trains, cars and even Greyhound buses. She has recounted her travels in her personal diary and recorded every experience with minute detail. She stayed 116 days, travelling through 19 states and 56 cities. “The Second Sex”, published in 1949, became a reference in the feminist movement but has certainly masked the talent of diarist Simone de Beauvoir. The careful observer, endowed with a chiselled and precise writing style, travelling was central guidance of the existential experience for her, a woman with infinite curiosity, a thirst for experiencing and discovering everything. In 1929, she made her first trips to Spain, Italy and England with her lifelong partner, the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. In 1947, she made, this time alone, her first trip to the United States, a trip that would have changed her life: "Usually, travelling is an attempt to annex a new object to my universe; this in itself is an undertaking: but today it’s different. -

M. H< Fass Collection

3^'W)albua í^txm s -DLM j Ajglt£r £\¿&ns : P haiq^io-pVVb -fo r M. H< fass Collection s e r ie s ■+tvß- Panivi ^ecQoVvf A dyvuVi >~St \ ¿ x t ^ n ,1*135' l*fö ¿ o ? o o ? ' 0 °l SUB SERIES b o x _____ __ ïr=t FOLDER. .... .... A f Photographs for the Farm Security Administration, 1935-1938 A Catalog of Photographic Prints Available from the Farm Security Administration Collection in the Library of Congress Introduction by Jerald C. Maddox A DACAPO PAPERBACK Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Da Capo Press. Walker Evans, photographs for the Farm Security Administration, 1935-1938. (A Da Capo paperback) 1. United States—Rural conditions—Pictorial works— Catalogs. 2. Photographs—Catalogs. I. Evans, Walker, 1903- II. Maddox, Jerald C. III. United States. Farm Security Administration. IV. United States. Library of Congress. V. Title. HN57.D22 1975 779'.9'3092630973 74-23992 ISBN 0-306-80008-X First Paperback Printing 1975 ISBN 0-306-80008-X Copyright © 1973 by Da Capo Press, Inc. All Rights Reserved The copyright on this volume does not apply individually to the photographs which are illustrated. These photographs, commissioned by the Farm Security Administra'ion, U.S. Department of Agriculture, are in the public domain and may be reproduced without permission. Published by Da Capo Press A Division of Plenum Publishing Corporation 227 West 17th Street, New York, N. Y. 10011 Manufactured in the United States of America Publisher’s Preface The Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress is the greatest repository of visual material documenting the development of the American nation. -

Oral History Interview with Walker Evans, 1971 Oct. 13-Dec. 23

Oral history interview with Walker Evans, 1971 Oct. 13-Dec. 23 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Walker Evans conducted by Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. The interview took place at the home of Walker Evans in Connecticut on October 13, 1971 and in his apartment in New York City on December 23, 1971. Interview PAUL CUMMINGS: It’s October 13, 1971 – Paul Cummings talking to Walker Evans at his home in Connecticut with all the beautiful trees and leaves around today. It’s gorgeous here. You were born in Kenilworth, Illinois – right? WALKER EVANS: Not at all. St. Louis. There’s a big difference. Though in St. Louis it was just babyhood, so really it amounts to the same thing. PAUL CUMMINGS: St. Louis, Missouri. WALKER EVANS: I think I must have been two years old when we left St. Louis; I was a baby and therefore knew nothing. PAUL CUMMINGS: You moved to Illinois. Do you know why your family moved at that point? WALKER EVANS: Sure. Business. There was an opening in an advertising agency called Lord & Thomas, a very famous one. I think Lasker was head of it. Business was just starting then, that is, advertising was just becoming an American profession I suppose you would call it. Anyway, it was very naïve and not at all corrupt the way it became later. -

Oral History Interview with Roy Emerson Stryker, 1963-1965

Oral history interview with Roy Emerson Stryker, 1963-1965 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Roy Stryker on October 17, 1963. The interview took place in Montrose, Colorado, and was conducted by Richard Doud for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview Side 1 RICHARD DOUD: Mr. Stryker, we were discussing Tugwell and the organization of the FSA Photography Project. Would you care to go into a little detail on what Tugwell had in mind with this thing? ROY STRYKER: First, I think I'll have to raise a certain question about your emphasis on the word "Photography Project." During the course of the morning I gave you a copy of my job description. It might be interesting to refer back to it before we get through. RICHARD DOUD: Very well. ROY STRYKER: I was Chief of the Historical Section, in the Division of Information. My job was to collect documents and materials that might have some bearing, later, on the history of the Farm Security Administration. I don't want to say that photography wasn't conceived and thought of by Mr. Tugwell, because my backround -- as we'll have reason to talk about later -- and my work at Columbia was very heavily involved in the visual. -

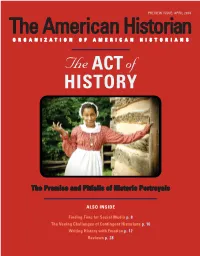

Preview Issue, the American Historian

PREVIEW ISSUE: APRIL 2014 The American Historian ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN HISTORIANS The ACT of HISTORY The Promise and Pitfalls of Historic Portrayals ALSO INSIDE Finding Time for Social Media p. 8 The Vexing Challenges of Contingent Historians p. 10 Writing History with Emotion p. 12 Reviews p. 28 Career and family... We’ve got you covered. Organization of American Historians’ member insurance plans and services have been carefully chosen for their valuable benefits at competitive group rates from a variety of reputable, highly-rated carriers. Professional Home & Auto • Professional Liability • GEICO Automobile Insurance • Private Practice Professional Liability • Homeowners Insurance • Student Educator Professional Liability • Pet Health Insurance Health Life • TIE Health Insurance Exchange • New York Life Group Term • New York Life Group Accidental Death Life Insurance† & Dismemberment Insurance† • New York Life 10 Year Level • Cancer Insurance Plan Group Term Life Insurance† • Medicare Supplement Insurance • Educators Dental Plan † Underwritten by New York Life Insurance Company, New York, NY 10010 Policy Form GMR. Please note: Not all plans are available in all states. Trust for Insuring Educators Administered by Forrest T. Jones & Company (800) 821-7303 • www.ftj.com/OAH Personalized Long Term Care Insurance Evaluation Featuring top insurance companies and special discounts. This advertisement is for informational purposes only and is not meant to define, alter, limit or expand any policy in any way. For a descriptive brochure that summarizes features, costs, eligibility, renewability, limitations and exclusions, call Forrest T. Jones & Company. Arkansas producer license #71740, California producer license #0592939. 2 The American Historian | April 2014 #6608 0314 6608 OAH All Coverage Ad.indd 1 2/26/14 3:46 PM Career and family.. -

1937-1943 Additional Excerpts

Wright State University CORE Scholar Books Authored by Wright State Faculty/Staff 1997 The Celebrative Spirit: 1937-1943 Additional Excerpts Ronald R. Geibert Wright State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/books Part of the Photography Commons Repository Citation Geibert , R. R. (1997). The Celebrative Spirit: 1937-1943 Additional Excerpts. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books Authored by Wright State Faculty/Staff by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Additional excerpts from the 1997 CD-ROM and 1986 exhibition The Celebrative Spirit: 1937-1943 John Collier’s work as a visual anthropologist has roots in his early years growing up in Taos, New Mexico, where his father was head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. His interest in Native Americans of the Southwest would prove to be a source of conflict with his future boss, Roy Stryker, director of the FSA photography project. A westerner from Colorado, Stryker did not consider Indians to be part of the mission of the FSA. Perhaps he worried about perceived encroachment by the FSA on BIA turf. Whatever the reason, the rancor of his complaints when Collier insisted on spending a few extra weeks in the West photographing native villages indicates Stryker may have harbored at least a smattering of the old western anti-Indian attitude. By contrast, Collier’s work with Mexican Americans was a welcome and encouraged addition to the FSA file. -

Children at the Mutoscope Dan Streible

Document généré le 27 sept. 2021 17:28 Cinémas Revue d'études cinématographiques Journal of Film Studies Children at the Mutoscope Dan Streible Dispositif(s) du cinéma (des premiers temps) Résumé de l'article Volume 14, numéro 1, automne 2003 À la fin des années 1890, les mutoscopes étaient associés aux productions dites pour adultes. Pourtant, ces appareils étaient souvent accessibles aux enfants. URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/008959ar Deux sources de documentation, la campagne du groupe de presse Hearst, en DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/008959ar 1899, contre « les images des galeries de l’enfer », ainsi que les photographies de la Farm Security Administration, remontant aux années 1930, permettent Aller au sommaire du numéro d’établir la longévité de la fréquentation des mutoscopes par la jeunesse américaine. La panique morale qu’instillait la rhétorique des journaux de Hearst fut de courte durée et servit surtout les intérêts du groupe de presse. Elle demeure cependant fort instructive pour qui s’intéresse à la manière dont Éditeur(s) les discours sur les nouveaux médias diffusent une même angoisse au cours de Cinémas tout le vingtième siècle. Au contraire, les photographies du FSA révèlent pour leur part que les indécences du mutoscope n’étaient ressenties comme telles que de façon marginale dans les années 1930. ISSN 1181-6945 (imprimé) 1705-6500 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Streible, D. (2003). Children at the Mutoscope. Cinémas, 14(1), 91–116. https://doi.org/10.7202/008959ar Tous droits réservés © Cinémas, 2003 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

Documenting the Dissin's Guest House: Esther Bubley's Exploration of Jewish-American Identity, 1942-43

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2013-06-03 Documenting the Dissin's Guest House: Esther Bubley's Exploration of Jewish-American Identity, 1942-43 Vriean Diether Taggart Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Taggart, Vriean Diether, "Documenting the Dissin's Guest House: Esther Bubley's Exploration of Jewish- American Identity, 1942-43" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 3599. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/3599 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Documenting the Dissin’s Guest House: Esther Bubley’s Exploration of Jewish- American Identity, 1942-43 Vriean 'Breezy' Diether Taggart A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts James Russel Swensen, Chair Marian E. Wardle Heather Jensen Department of Visual Arts Brigham Young University May 2013 Copyright © 2013 Vriean 'Breezy' Diether Taggart All rights reserved ABSTRACT Documenting the Dissin’s Guest House: Esther Bubley’s Exploration of Jewish- American Identity, 1942-43 Vriean 'Breezy' Diether Taggart Department of Visual Arts Master of Arts This thesis considers Esther Bubley’s photographic documentation of a boarding house for Jewish workingmen and women during World War II. An examination of Bubley’s photographs reveals the complexities surrounding Jewish-American identity, which included aspects of social inclusion and exclusion, a rejection of past traditions and acceptance of contemporary transitions. -

Fall 2018 Alumni Magazine

University Advancement NONPROFIT ORG PO Box 2000 U.S. POSTAGE Superior, Wisconsin 54880-4500 PAID DULUTH, MN Travel with Alumni and Friends! PERMIT NO. 1003 Rediscover Cuba: A Cultural Exploration If this issue is addressed to an individual who no longer uses this as a permanent address, please notify the Alumni Office at February 20-27, 2019 UW-Superior of the correct mailing address – 715-394-8452 or Join us as we cross a cultural divide, exploring the art, history and culture of the Cuban people. Develop an understanding [email protected]. of who they are when meeting with local shop keepers, musicians, choral singers, dancers, factory workers and more. Discover Cuba’s history visiting its historic cathedrals and colonial homes on city tours with your local guide, and experience one of the world’s most culturally rich cities, Havana, and explore much of the city’s unique architecture. Throughout your journey, experience the power of travel to unite two peoples in a true cultural exchange. Canadian Rockies by Train September 15-22, 2019 Discover the western Canadian coast and the natural beauty of the Canadian Rockies on a tour featuring VIA Rail's overnight train journey. Begin your journey in cosmopolitan Calgary, then discover the natural beauty of Lake Louise, Moraine Lake, and the powerful Bow Falls and the impressive Hoodoos. Feel like royalty at the grand Fairmont Banff Springs, known as the “Castle in the Rockies,” where you’ll enjoy a luxurious two-night stay in Banff. Journey along the unforgettable Icefields Parkway, with a stop at Athabasca Glacier and Peyto Lake – a turquoise glacier-fed treasure that evokes pure serenity – before arriving in Jasper, nestled in the heart of the Canadian Rockies. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

THE CRITICISM OF ROBERT FRANK'S "THE AMERICANS" Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alexander, Stuart Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 11:13:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/277059 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. -

Farm Security Administation Photographs in Indiana

FARM SECURITY ADMINISTRATION PHOTOGRAPHS IN INDIANA A STUDY GUIDE Roy Stryker Told the FSA Photographers “Show the city people what it is like to live on the farm.” TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 The FSA - OWI Photographic Collection at the Library of Congress 1 Great Depression and Farms 1 Roosevelt and Rural America 2 Creation of the Resettlement Administration 3 Creation of the Farm Security Administration 3 Organization of the FSA 5 Historical Section of the FSA 5 Criticisms of the FSA 8 The Indiana FSA Photographers 10 The Indiana FSA Photographs 13 City and Town 14 Erosion of the Land 16 River Floods 16 Tenant Farmers 18 Wartime Stories 19 New Deal Communities 19 Photographing Indiana Communities 22 Decatur Homesteads 23 Wabash Farms 23 Deshee Farms 24 Ideal of Agrarian Life 26 Faces and Character 27 Women, Work and the Hearth 28 Houses and Farm Buildings 29 Leisure and Relaxation Activities 30 Afro-Americans 30 The Changing Face of Rural America 31 Introduction This study guide is meant to provide an overall history of the Farm Security Administration and its photographic project in Indiana. It also provides background information, which can be used by students as they carry out the curriculum activities. Along with the curriculum resources, the study guide provides a basis for studying the history of the photos taken in Indiana by the FSA photographers. The FSA - OWI Photographic Collection at the Library of Congress The photographs of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) - Office of War Information (OWI) Photograph Collection at the Library of Congress form a large-scale photographic record of American life between 1935 and 1944.