M. H< Fass Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pressemappe American Photography

Exhibition Facts Duration 24 August – 28 November 2021 Virtual Opening 23. August 2021 | 6.30 PM | on Facebook-Live & YouTube Venue Bastion Hall Curator Walter Moser Co-Curator Anna Hanreich Works ca. 180 Catalogue Available for EUR EUR 29,90 (English & German) onsite at the Museum Shop as well as via www.albertina.at Contact Albertinaplatz 1 | 1010 Vienna T +43 (01) 534 83 0 [email protected] www.albertina.at Opening Hours Daily 10 am – 6 pm Press contact Daniel Benyes T +43 (01) 534 83 511 | M +43 (0)699 12178720 [email protected] Sarah Wulbrandt T +43 (01) 534 83 512 | M +43 (0)699 10981743 [email protected] 2 American Photography 24 August - 28 November 2021 The exhibition American Photography presents an overview of the development of US American photography between the 1930s and the 2000s. With works by 33 artists on display, it introduces the essential currents that once revolutionized the canon of classic motifs and photographic practices. The effects of this have reached far beyond the country’s borders to the present day. The main focus of the works is on offering a visual survey of the United States by depicting its people and their living environments. A microcosm frequently viewed through the lens of everyday occurrences permits us to draw conclusions about the prevalent political circumstances and social conditions in the United States, capturing the country and its inhabitants in their idiosyncrasies and contradictions. In several instances, artists having immigrated from Europe successfully perceived hitherto unknown aspects through their eyes as outsiders, thus providing new impulses. -

Oral History Interview with Walker Evans, 1971 Oct. 13-Dec. 23

Oral history interview with Walker Evans, 1971 Oct. 13-Dec. 23 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Walker Evans conducted by Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. The interview took place at the home of Walker Evans in Connecticut on October 13, 1971 and in his apartment in New York City on December 23, 1971. Interview PAUL CUMMINGS: It’s October 13, 1971 – Paul Cummings talking to Walker Evans at his home in Connecticut with all the beautiful trees and leaves around today. It’s gorgeous here. You were born in Kenilworth, Illinois – right? WALKER EVANS: Not at all. St. Louis. There’s a big difference. Though in St. Louis it was just babyhood, so really it amounts to the same thing. PAUL CUMMINGS: St. Louis, Missouri. WALKER EVANS: I think I must have been two years old when we left St. Louis; I was a baby and therefore knew nothing. PAUL CUMMINGS: You moved to Illinois. Do you know why your family moved at that point? WALKER EVANS: Sure. Business. There was an opening in an advertising agency called Lord & Thomas, a very famous one. I think Lasker was head of it. Business was just starting then, that is, advertising was just becoming an American profession I suppose you would call it. Anyway, it was very naïve and not at all corrupt the way it became later. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

THE CRITICISM OF ROBERT FRANK'S "THE AMERICANS" Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alexander, Stuart Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 11:13:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/277059 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. -

Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci, with a Short Story by Jeffrey Eugenides

Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci, with a short story by Jeffrey Eugenides Author Marcoci, Roxana Date 2005 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art ISBN 0870700804 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/116 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art museumof modern art lIOJ^ArxxV^ 9 « Thomas Demand Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci with a short story by Jeffrey Eugenides The Museum of Modern Art, New York Published in conjunction with the exhibition Thomas Demand, organized by Roxana Marcoci, Assistant Curator in the Department of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 4-May 30, 2005 The exhibition is supported by Ninah and Michael Lynne, and The International Council, The Contemporary Arts Council, and The Junior Associates of The Museum of Modern Art. This publication is made possible by Anna Marie and Robert F. Shapiro. Produced by the Department of Publications, The Museum of Modern Art, New York Edited by Joanne Greenspun Designed by Pascale Willi, xheight Production by Marc Sapir Printed and bound by Dr. Cantz'sche Druckerei, Ostfildern, Germany This book is typeset in Univers. The paper is 200 gsm Lumisilk. © 2005 The Museum of Modern Art, New York "Photographic Memory," © 2005 Jeffrey Eugenides Photographs by Thomas Demand, © 2005 Thomas Demand Copyright credits for certain illustrations are cited in the Photograph Credits, page 143. Library of Congress Control Number: 2004115561 ISBN: 0-87070-080-4 Published by The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York, New York 10019-5497 (www.moma.org) Distributed in the United States and Canada by D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, New York Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Thames & Hudson Ltd., London Front and back covers: Window (Fenster). -

Exegesis. Christopher Shawne Brown East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2008 Exegesis. Christopher Shawne Brown East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Photography Commons Recommended Citation Brown, Christopher Shawne, "Exegesis." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1903. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1903 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXEGESIS A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Art & Design East Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts ________________________ by Christopher Shawne Brown May 2008 ___________________ Mike Smith, Committee Chair Dr. Scott Contreras-Koterbay Catherine Murray M. Wayne Dyer Keywords: photography, family album, color, influence, landscape, home, collector A B S TRACT Exegesis by Christopher Shawne Brown The photographer discusses the work in Exegesis, his Master of Fine Arts exhibition held at Slocumb Galleries, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, Tennessee from October 29 through November 2, 2007. The exhibition consists of 19 large format color photographs representing and edited from a body of work that visually negotiates the photographer’s home in East Tennessee. The formulation of a web of influence is explored with a focus on artists who continue to pertain to Brown’s work formally and conceptually. -

Tender Land Study Guide

AARON COPLAND’S INSPIRING AMERICAN OPERA THE TENDER LAND FRIDAY OCTOBER 13TH 7:00 PM SUNDAY OCTOBER 15TH 3:00 PM WILLSON AUDITORIUM Celebrating 4 Seasons Tickets available at Intermountainopera.org or 406-587-2889 TABLE OF CONTENTS Intermountain Opera Bozeman ……………………………………………...3 The Tender Land Characters and Synopsis…….………………….….…5 The Composer and Librettist…………………………………………….6 The Tender Land Background and Inspiration……………..…………..9 Historical Context and Timeline…………………………………….….13 Further Exploration……………………………………………….…..…20 !2 Intermountain Opera Bozeman In 1978, Verity Bostick, a young singer and assistant professor of music at Montana State University at Bozeman, sparked the interest of a well-known New York opera producer, Anthony Stivanello, with her desire to form the first Montana-based opera company. For the inaugural performance of Verdi’s La Traviata in the Spring of 1979, Mr. Stivanello agreed to donate sets, costumes and his services to the production. Gallatin Valley had its own resident opera star, Pablo Elvira, who was persuaded to share his talents. A leading baritone with the Metropolitan Opera and New York City Opera, he sang Germont in La Traviata. A full-fledged professional opera company in Bozeman, MT was born! With names like Elvira and Stivanello appearing, Montana suddenly caught the interest of Eastern opera circles. The prestigious opera magazine, Opera News, assigned a reporter to cover the advent of the Intermountain Opera Association’s first year. During the second season, the Association produced The Barber of Seville, starring Pablo Elvira, and brought three stars from New York to sing leading roles. Anthony Stivanello again furnished sets and costumes and directed the production. -

Sccopland on The

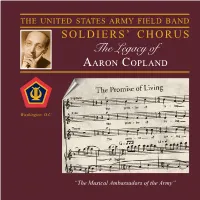

THE UNITED STATES ARMY FIELD BAND SOLDIERS’ CHORUS The Legacy of AARON COPLAND Washington, D.C. “The Musical Ambassadors of the Army” he Soldiers’ Chorus, founded in 1957, is the vocal complement of the T United States Army Field Band of Washington, DC. The 29-member mixed choral ensemble travels throughout the nation and abroad, performing as a separate component and in joint concerts with the Concert Band of the “Musical Ambassadors of the Army.” The chorus has performed in all fifty states, Canada, Mexico, India, the Far East, and throughout Europe, entertaining audiences of all ages. The musical backgrounds of Soldiers’ Chorus personnel range from opera and musical theatre to music education and vocal coaching; this diversity provides unique programming flexibility. In addition to pre- senting selections from the vast choral repertoire, Soldiers’ Chorus performances often include the music of Broadway, opera, barbershop quartet, and Americana. This versatility has earned the Soldiers’ Chorus an international reputation for presenting musical excellence and inspiring patriotism. Critics have acclaimed recent appearances with the Boston Pops, the Cincinnati Pops, and the Detroit, Dallas, and National symphony orchestras. Other no- table performances include four world fairs, American Choral Directors Association confer- ences, music educator conven- tions, Kennedy Center Honors Programs, the 750th anniversary of Berlin, and the rededication of the Statue of Liberty. The Legacy of AARON COPLAND About this Recording The Soldiers’ Chorus of the United States Army Field Band proudly presents the second in a series of recordings honoring the lives and music of individuals who have made significant contributions to the choral reper- toire and to music education. -

Sfmoma to Feature Exclusive U.S. Presentation of the Exhibition, Walker Evans

SFMOMA TO FEATURE EXCLUSIVE U.S. PRESENTATION OF THE EXHIBITION, WALKER EVANS Exhibition Displays Over 400 Photographs, Paintings, Graphic Ephemera and Objects from the Artist’s Personal Collection Walker Evans September 30, 2017–February 4, 2018 SAN FRANCISCO, CA (May 18, 2017)—The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) will be the exclusive United States venue for the retrospective exhibition Walker Evans, on view September 30, 2017, through February 4, 2018. As one of the preeminent photographers of the 20th century, Walker Evans’ 50-year body of work documents and distills the essence of life in America, leaving a legacy that continues to influence generations of contemporary photographers and artists. The exhibition will encompass all galleries in the museum's Pritzker Center for Photography, the largest space dedicated to the exhibition, study and interpretation of photography at any art museum in the United States. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Walker Evans Press Release 1 “Conceived as a complete retrospective of Evans’ work, this exhibition highlights the photographer’s fascination with American popular culture, or vernacular,” explains Clément Chéroux, senior curator of photography at SFMOMA. “Evans was intrigued by the vernacular as both a subject and a method. By elevating it to the rank of art, he created a unique body of work celebrating the beauty of everyday life.” Using examples from Evans’ most notable photographs—including iconic images from his work for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) documenting the effects of the Great Depression on American life; early visits to Cuba; street photography and portraits made on the New York City subway; layouts and portfolios from his more than 20-year collaboration with Fortune magazine and 1970s Polaroids— Walker Evans explores Evans’ passionate search for the fundamental characteristics of American vernacular culture: the familiar, quotidian street language and symbols through which a society tells its own story. -

For Immediate Release High Museum of Art Is Sole U.S

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE HIGH MUSEUM OF ART IS SOLE U.S. VENUE FOR INTERNATIONAL TOUR OF WALKER EVANS PHOTOGRAPHY Co-organized exhibition marks the most comprehensive retrospective of Evans’ work to be presented in Europe, Canada and the American South ATLANTA, May 17, 2016 – The High Museum of Art in Atlanta is partnering with the Josef Albers Museum Quadrat (Bottrop, Germany) and the Vancouver Art Gallery to present a major touring retrospective of the work of Walker Evans, one of the most influential documentary photographers of the 20th century. The High will be the only U.S. venue for “Walker Evans: Depth of Field,” which places Evans’ most recognized photographs within the larger context of his 50-year career. The exhibition is among the most thorough examinations ever presented of the photographer’s work and the most comprehensive Evans retrospective to be mounted in Europe, Canada and the southeastern United States. Following its presentation at the Josef Albers Museum Quadrat, the exhibition will be presented at the High from June 11 through Sept. 11, 2016, before traveling to Vancouver (Oct. 29, 2016, through Jan. 22, 2017). The High’s presentation will feature more than 120 black-and-white and color prints from the 1920s through the 1970s, including photographs from the Museum’s permanent collection. With a profundity that has not previously been accomplished, the exhibition and its companion publication explore the transatlantic roots and repercussions of Evans’ contributions to the field of photography and examine his pioneering of the lyric documentary style, which fuses a powerful personal perspective with the objective record of time and place. -

GEN MS 05 Walker Evans Photographs Finding Aid

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Search the General Manuscript Collection Finding Aids General Manuscript Collection 3-2018 GEN MS 05 Walker Evans Photographs Finding Aid Siobain C. Monahan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/manuscript_finding_aids Part of the American Studies Commons, Photography Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Walker Evans Photographs, Special Collections, University of Southern Maine Libraries. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the General Manuscript Collection at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Search the General Manuscript Collection Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS WALKER EVANS PHOTOGRAPHS GEN MS 5 Total Boxes: 3 Linear Feet: 4.5 By Siobain C. Monahan Portland, Maine December, 2000 Copyright 2000 by the University of Southern Maine Administrative Information Provenance: In 1970, Juris Ubans, as Director of the Art Gallery was trying to create inexpensive exhibitions. While at the Library of Congress for a John Ford film festival, he stumbled across the Farm Security Administration Act photographs, and thus the Walker and Shahn photographs. With the 150th anniversary of USM in 1974, he decided to get copies of (or in Walker's case prints from the original negatives) photographs related mostly to Maine and New England. In 1991, the exhibition created with the Ben Shahn photographs traveled to Leningrad in the then Soviet Union. This information was provided by Juris Ubans to Susie R. -

Walker Evans: Depth of Field

Walker Evans: Depth of Field Silhouette Self-Portrait, Juan-les-Pins, France, January 1927 Stare. It is the way to educate your eye, and more. Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop. Die knowing something. You are not here long. Walker Evans Walker Evans: Depth of Field Edited by John T. Hill and Heinz Liesbrock Essays by John T. Hill Heinz Liesbrock Jerry L. Thompson Alan Trachtenberg Thomas Weski Josef Albers Museum Quadrat, Bottrop High Museum of Art, Atlanta Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver Prestel • Munich • London • New York Walker Evans with His Father and Grandfather Walker Evans II, Walker Evans III, Walker Evans I Contents 12 Directors’ Foreword 14 Patrons’ Remarks 16 Introduction John T. Hill 19 “A surgeon operating on the fluid body of time”: The Historiography and Poetry of Walker Evans Heinz Liesbrock 30 Chapter 1 Origins and Early Work 1926–1931 94 Chapter 2 Portraits 95 “Quiet and true”: The Portrait Photographs of Walker Evans Jerry L. Thompson 112 Chapter 3 Victorian Architecture 1931–1934 126 Chapter 4 Cuba 1933 142 Chapter 5 African Sculpture 1934–1935 148 Chapter 6 Antebellum Architecture 1935–1936 162 Chapter 7 Farm Security Administration 1935–1938 200 Chapter 8 Let Us Now Praise Famous Men 222 “The most literary of the graphic arts”: Walker Evans on Photography Alan Trachtenberg 232 Chapter 9 New York Subway Portraits 1938–1941 248 Chapter 10 Mangrove Coast 1941 261 The Cruel and Tender Camera Thomas Weski and Heinz Liesbrock 274 Chapter 11 Magazine Essays 1945–1965 334 Chapter 12 Late Work 1960 –1970s 346 A “last lap around the track”: Signs and SX-70s Jerry L. -

Reshaping American Music: the Quotation of Shape-Note Hymns by Twentieth-Century Composers

RESHAPING AMERICAN MUSIC: THE QUOTATION OF SHAPE-NOTE HYMNS BY TWENTIETH-CENTURY COMPOSERS by Joanna Ruth Smolko B.A. Music, Covenant College, 2000 M.M. Music Theory & Composition, University of Georgia, 2002 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Faculty of Arts and Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in Historical Musicology University of Pittsburgh 2009 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Joanna Ruth Smolko It was defended on March 27, 2009 and approved by James P. Cassaro, Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Music Mary S. Lewis, Professor, Department of Music Alan Shockley, Assistant Professor, Cole Conservatory of Music Philip E. Smith, Associate Professor, Department of English Dissertation Advisor: Deane L. Root, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Joanna Ruth Smolko 2009 iii RESHAPING AMERICAN MUSIC: THE QUOTATION OF SHAPE-NOTE HYMNS BY TWENTIETH-CENTURY COMPOSERS Joanna Ruth Smolko, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Throughout the twentieth century, American composers have quoted nineteenth-century shape- note hymns in their concert works, including instrumental and vocal works and film scores. When referenced in other works the hymns become lenses into the shifting web of American musical and national identity. This study reveals these complex interactions using cultural and musical analyses of six compositions from the 1930s to the present as case studies. The works presented are Virgil Thomson’s film score to The River (1937), Aaron Copland’s arrangement of “Zion’s Walls” (1952), Samuel Jones’s symphonic poem Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1974), Alice Parker’s opera Singers Glen (1978), William Duckworth’s choral work Southern Harmony and Musical Companion (1980-81), and the score compiled by T Bone Burnett for the film Cold Mountain (2003).