Unemployment Rate Falls in August

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neoliberal Austerity and Unemployment

E L C I ‘…following Stuckler and Basu (2013) T it is not economic downturns per se that R matter but the austerity and welfare A “reform” that may follow: that “austerity Neoliberal austerity kills” and – as I argue here – that it particularly “kills” those in lower socio- economic positions.’ and unemployment The scale of contemporary unemployment consequent upon David Fryer and Rose Stambe examine critical psychological issues neoliberal austerity programmes is colossal. According to labour market statistics released in June 2013 by the UK Neoliberal fiscal austerity policies I am really sorry to bother you again. Office for National Statistics, 2.51 million decrease public expenditure God. But I am bursting to tell you all people were unemployed in the UK through cuts to central and local the stuff that has been going on (tinyurl.com/neu9l47). This represents five government budgets, welfare behind your back since I first wrote to unemployed people competing for every services and benefits and you back in 1988. Oh God do you still vacancy. privatisation of public resources remember? Remember me telling Official statistics like these, which have resulting in job losses. This article you of the war that was going on persisted now for years, do not, of course, interrogates the empirical, against the poor and unemployed in prevent the British Prime Minister – theoretical, methodological and our working class communities? Do evangelist of neoliberal government - ideological relationships between you remember me telling you, God, asking in a speech delivered in June 2012 neoliberalism, unemployment and how the people in my community ‘Why has it become acceptable for many the discipline of psychology, were being killed and terrorised but people to choose a life on benefits?’ arguing that neoliberalism that there were no soldiers to be Talking of what he termed ‘Working Age constitutes rather than causes seen, no tanks, no bombs being Welfare’, Mr Cameron opined: ‘we have unemployment. -

Unemployment in an Extended Cournot Oligopoly Model∗

Unemployment in an Extended Cournot Oligopoly Model∗ Claude d'Aspremont,y Rodolphe Dos Santos Ferreiraz and Louis-Andr´eG´erard-Varetx 1 Introduction Attempts to explain unemployment1 begin with the labour market. Yet, by attributing it to deficient demand for goods, Keynes questioned the use of partial analysis, and stressed the need to consider interactions between the labour and product markets. Imperfect competition in the labour market, reflecting union power, has been a favoured explanation; but imperfect competition may also affect employment through producers' oligopolistic behaviour. This again points to a general equilibrium approach such as that by Negishi (1961, 1979). Here we propose an extension of the Cournot oligopoly model (unlike that of Gabszewicz and Vial (1972), where labour does not appear), which takes full account of the interdependence between the labour market and any product market. Our extension shares some features with both Negishi's conjectural approach to demand curves, and macroeconomic non-Walrasian equi- ∗Reprinted from Oxford Economic Papers, 41, 490-505, 1989. We thank P. Champsaur, P. Dehez, J.H. Dr`ezeand J.-J. Laffont for helpful comments. We owe P. Dehez the idea of a light strengthening of the results on involuntary unemployment given in a related paper (CORE D.P. 8408): see Dehez (1985), where the case of monopoly is studied. Acknowledgements are also due to Peter Sinclair and the Referees for valuable suggestions. This work is part of the program \Micro-d´ecisionset politique ´economique"of Commissariat G´en´eral au Plan. Financial support of Commissariat G´en´eralau Plan is gratefully acknowledged. -

Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism

DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS, ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT & TOURISM RESEARCH AND ECONOMIC ANALYSIS DIVISION DAVID Y. IGE GOVERNOR MIKE MC CARTNEY DIRECTOR DR. EUGENE TIAN CHIEF STATE ECONOMIST FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 19, 2021 HAWAI‘I'S UNEMPLOYMENT RATE AT 7.3 PERCENT IN JULY Jobs increased by 53,000 over-the-year HONOLULU — The Hawai‘i State Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism (DBEDT) today announced that the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate for July was 7.3 percent compared to 7.7 percent in June. Statewide, 598,850 were employed and 47,200 unemployed in July for a total seasonally adjusted labor force of 646,000. Nationally, the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was 5.4 percent in July, down from 5.9 percent in June. Seasonally Adjusted Unemployment Rate State of Hawai`i Jul 2019 - Jul 2021 28.0% 24.0% 20.0% 16.0% 12.0% 8.0% 4.0% 0.0% Ma Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr Ma Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr Jun Jul y 19 19 19 19 19 19 20 20 20 20 y20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 21 21 21 21 21 21 21 Percent 2.5 2.4 2.3 2.2 2.1 2.1 2.0 2.1 2.1 21. 21. 14. 14. 14. 14. 14. 10. 10. 10. 9.2 9.1 8.5 8.0 7.7 7.3 The unemployment rate figures for the State of Hawai‘i and the U.S. in this release are seasonally adjusted, in accordance with the U.S. -

Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits

Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits Julie M. Whittaker Specialist in Income Security Katelin P. Isaacs Analyst in Income Security March 28, 2012 The House Ways and Means Committee is making available this version of this Congressional Research Service (CRS) report, with the cover date shown, for inclusion in its 2012 Green Book website. CRS works exclusively for the United States Congress, providing policy and legal analysis to Committees and Members of both the House and Senate, regardless of party affiliation. Congressional Research Service R42444 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits Summary The temporary Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08) program may provide additional federal unemployment insurance benefits to eligible individuals who have exhausted all available benefits from their state Unemployment Compensation (UC) programs. Congress created the EUC08 program in 2008 and has amended the original, authorizing law (P.L. 110-252) 10 times. The most recent extension of EUC08 in P.L. 112-96, the Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012, authorizes EUC08 benefits through the end of calendar year 2012. P.L. 112- 96 also alters the structure and potential availability of EUC08 benefits in states. Under P.L. 112- 96, the potential duration of EUC08 benefits available to eligible individuals depends on state unemployment rates as well as the calendar date. The P.L. 112-96 extension of the EUC08 program does not allow any individual to receive more than 99 weeks of total unemployment insurance (i.e., total weeks of benefits from the three currently authorized programs: regular UC plus EUC08 plus EB). -

Modern Monetary Theory: a Marxist Critique

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 1 2019 Modern Monetary Theory: A Marxist Critique Michael Roberts [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Roberts, Michael (2019) "Modern Monetary Theory: A Marxist Critique," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.7.1.008316 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol7/iss1/1 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Monetary Theory: A Marxist Critique Abstract Compiled from a series of blog posts which can be found at "The Next Recession." Modern monetary theory (MMT) has become flavor of the time among many leftist economic views in recent years. MMT has some traction in the left as it appears to offer theoretical support for policies of fiscal spending funded yb central bank money and running up budget deficits and public debt without earf of crises – and thus backing policies of government spending on infrastructure projects, job creation and industry in direct contrast to neoliberal mainstream policies of austerity and minimal government intervention. Here I will offer my view on the worth of MMT and its policy implications for the labor movement. First, I’ll try and give broad outline to bring out the similarities and difference with Marx’s monetary theory. -

July Unemployment Rate Decreases to 5.8 Percent

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: September 16, 2021 Margaux Fontaine 401-209-0153 [email protected] Rhode Island-Based Jobs Rose by 800 from July; August Unemployment Rate Increases to 5.8 Percent CRANSTON, R.I. - The state’s seasonally adjusted Aug 21 Jul 21 Aug 20 unemployment rate was 5.8 percent in August, the Department of R.I. Unemployment Rate 5.8% 5.7% 12.6% Labor and Training announced Thursday. The August rate was up one-tenth of a percentage point from the revised July rate of 5.7 U.S. Unemployment Rate 5.2% 5.4% 8.4% percent. Last year the rate was 12.6 percent in August. R.I. Job Count (in thousands) 477.9 477.1 457.3 Highlights: The U.S. unemployment rate was 5.2 percent in August, down two-tenths of a percentage point from July. The U.S. rate was 8.4 The Rhode Island unemployment rate was 5.8 percent percent in August 2020. in August, up one-tenth of a percentage point from last month’s revised rate of 5.7 percent. The number of unemployed Rhode Island residents — those Through August, the Rhode Island economy has residents classified as available for and actively seeking recovered 78,700 or nearly 73 percent of the 108,000 jobs lost during the pandemic shutdown. employment — was 30,900, up 100 from July. The number of unemployed residents decreased by 35,800 over the year. The number of employed Rhode Island residents was 503,800, down 1,500 from July. -

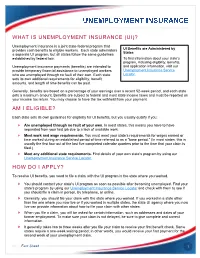

What Is Unemployment Insurance (Ui)? Am I Eligible? How Do I Apply?

WHAT IS UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE (UI)? Unemployment Insurance is a joint state-federal program that provides cash benefits to eligible workers. Each state administers UI Benefits are Administered by States a separate UI program, but all states follow the same guidelines established by federal law. To find information about your state’s program, including eligibility, benefits, Unemployment insurance payments (benefits) are intended to and application information, visit our provide temporary financial assistance to unemployed workers Unemployment Insurance Service who are unemployed through no fault of their own. Each state Locator. sets its own additional requirements for eligibility, benefit amounts, and length of time benefits can be paid. Generally, benefits are based on a percentage of your earnings over a recent 52-week period, and each state sets a maximum amount. Benefits are subject to federal and most state income taxes and must be reported on your income tax return. You may choose to have the tax withheld from your payment. AM I ELIGIBLE? Each state sets its own guidelines for eligibility for UI benefits, but you usually qualify if you: Are unemployed through no fault of your own. In most states, this means you have to have separated from your last job due to a lack of available work. Meet work and wage requirements. You must meet your state’s requirements for wages earned or time worked during an established period of time referred to as a "base period." (In most states, this is usually the first four out of the last five completed calendar quarters prior to the time that your claim is filed.) Meet any additional state requirements. -

Long-Term Unemployment and the 99Ers

Long-Term Unemployment and the 99ers An Emerging Issues Report from the January 2012 Long-Term Unemployment and the 99ers The Issue Long-term unemployment has been the most stubborn consequence of the Great Recession. In October 2011, more than two years after the Great Recession officially ended, the national unemployment rate stood at 9.0%, with Connecticut’s unemployment rate at 8.7%.1 Americans have been taught to connect the economic condition of the country or their state to the unemployment Millions of Americans— rate, but the national or state unemployment rate does not tell known as 99ers—have the real story. Concealed in those statistics is evidence of a exhausted their UI benefits, substantial and challenging structural change in the labor and their numbers grow market. Nationally, in July 2011, 31.8% of unemployed people every month. had been out of work for at least 52 weeks. In Connecticut, data shows 37% of the unemployed had been jobless for a year or more. By August 2011, the national average length of unemployment was a record 40 weeks.2 Many have been out of work far longer, with serious consequences. Even with federal extensions to Unemployment Insurance (UI), payments are available for a maximum of 99 weeks in some states; other states provide fewer (60-79) weeks. Millions of Americans—known as 99ers— have exhausted their UI benefits, and their numbers grow every month. By October 2011, approximately 2.9 million nationally had done so. Projections show that five million people will be 99ers, exhausting their benefits, by October 2012. -

The Great Recession, Jobless Recoveries and Black Workers

unemployment rate remains elevated at 9.5 for at least six months. The latter is a more The Great Recession, percent and many economists worry that the expansive measure that includes officially country is, at best, in a jobless recovery similar unemployed workers, discouraged workers Jobless Recoveries to what occurred after the 1990 and 2001 who have stopped looking for work and those recessions. At worst, we may be heading working part-time who are unable to find and Black Workers into a dreaded double-dip. For the black full-time employment. community, the Great Recession has been Sylvia Allegretto, Ph.D. and Steven Pitts, Ph.D. catastrophic, and the prospect of a jobless Using these three measures, a portrait of the recovery or further recession will extend the current state of black workers can be drawn. widespread economic and social woes in In July 2010, the official unemployment rate The economic downturn, which began in which much of the community is now mired. for black workers was 15.6 percent. When December 2007, aptly has been called the disaggregated by gender, one finds that 17.8 Great Recession. The trough of job losses The State of Black Workers percent of black men were unemployed occurred in December 2009, by which time since the Beginning of the Great and 13.7 percent of black women were 8.4 million or 6.1 percent of all non-farm Recession unemployed. For black youth (ages 16- jobs were lost. This represented the largest 19), unemployment stood at 40.6 percent. decline of jobs (in either absolute numbers or The most oft-cited measure of labor market (Comparable figures for whites were 8.6 percentage terms) since the Great Depression distress is the official unemployment rate. -

The Labor Market and the Phillips Curve

4 The Labor Market and the Phillips Curve A New Method for Estimating Time Variation in the NAIRU William T. Dickens The non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) is fre- quently employed in fiscal and monetary policy deliberations. The U.S. Congressional Budget Office uses estimates of the NAIRU to compute potential GDP, that in turn is used to make budget projections that affect decisions about federal spending and taxation. Central banks consider estimates of the NAIRU to determine the likely course of inflation and what actions they should take to preserve price stability. A problem with the use of the NAIRU in policy formation is that it is thought to change over time (Ball and Mankiw 2002; Cohen, Dickens, and Posen 2001; Stock 2001; Gordon 1997, 1998). But estimates of the NAIRU and its time variation are remarkably imprecise and are far from robust (Staiger, Stock, and Watson 1997, 2001; Stock 2001). NAIRU estimates are obtained from estimates of the Phillips curve— the relationship between the inflation rate, on the one hand, and the unemployment rate, measures of inflationary expectations, and variables representing supply shocks on the other. Typically, inflationary expecta- tions are proxied with several lags of inflation and the unemployment rate is entered with lags as well. The NAIRU is recovered as the constant in the regression divided by the coefficient on unemployment (or the sum of the coefficient on unemployment and its lags). The notion that the NAIRU might vary over time goes back at least to Perry (1970), who suggested that changes in the demographic com- position of the labor force would change the NAIRU. -

The Phillips Curve Evaluating Short-Run Inflation/Unemployment Dynamics

The Phillips Curve Evaluating Short-Run Inflation/Unemployment Dynamics Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Outline 1. Inflation-Unemployment Trade-Off 2. Phillips Curve 3. Zero Bound for Inflation • Textbook Readings: Ch. 17 Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Discovery of Short-Run Trade-Off between � and U • Phillips curve: A curve showing the short-run inverse relationship between the unemployment rate and the inflation rate • Named after economist A. W. Phillips (1958) Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Is The Phillips Curve A Policy Menu? • During the 1960s, some economists argued that the Phillips curve was a structural relationship: § A relationship that depends on the basic behavior of consumers and firms, and that remains unchanged over a long period • If this was true, policy-makers could choose a point on the curve Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University AD/AS Model Helps Us Derive the Phillips Curve • Recall: § The short-run macroeconomic equilibrium occurs when the AD and SRAS curves intersect § The long-run macroeconomic equilibrium occurs when the AD and SRAS curves intersect at the LRAS Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Short-Run Equilibrium Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Long-Run Equilibrium Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Short-Run vs Long-Run Equilibrium • We began in long run equilibrium: AD = SRAS = LRAS • G increased, increasing AD: AD = SRAS ≠ LRAS • This drives prices up, wage earners -

Unemployment Insurance: a Guide to Collecting Benefits in the State of Connecticut

Unemployment Insurance: A Guide to Collecting Benefits in the State of Connecticut DISPONIBLE EN ESPAÑOL Visite su oficina local del Departamento de Trabajo o visite Su oficina local del Departamento de Trabajo You are responsible for understanding your rights and responsibilities outlined in this booklet. Please be sure to read it in its entirety. ¡IMPORTANTE! Usted es responsable de comprender sus derechos y responsabilidades que se describen en este folleto. ¡Asegúrese de leerlo todo! . Visit our Unemployment Website: www.FileCTUI.com 1 | P a g e Table of Contents General Information to the Unemployment Insurance Claimant ........................................................................................... 4 What Is Unemployment Insurance? ................................................................................................................................... 4 Who is Protected by Unemployment Insurance? ............................................................................................................... 4 Your Legal Right to File a Claim ........................................................................................................................................... 4 How Do I Apply for Unemployment Insurance Benefits? ....................................................................................................... 5 Filing an Initial (New) Claim ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Reopening