Jessica Garpvall, Master's Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: to Stop the Defamation of the Jewish People and to Secure Justice and Fair Treatment for All

A report from the Center on Extremism 09 18 New Hate and Old: The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment for all. ABOUT T H E CENTER ON EXTREMISM The ADL Center on Extremism (COE) is one of the world’s foremost authorities ADL (Anti-Defamation on extremism, terrorism, anti-Semitism and all forms of hate. For decades, League) fights anti-Semitism COE’s staff of seasoned investigators, analysts and researchers have tracked and promotes justice for all. extremist activity and hate in the U.S. and abroad – online and on the ground. The staff, which represent a combined total of substantially more than 100 Join ADL to give a voice to years of experience in this arena, routinely assist law enforcement with those without one and to extremist-related investigations, provide tech companies with critical data protect our civil rights. and expertise, and respond to wide-ranging media requests. Learn more: adl.org As ADL’s research and investigative arm, COE is a clearinghouse of real-time information about extremism and hate of all types. COE staff regularly serve as expert witnesses, provide congressional testimony and speak to national and international conference audiences about the threats posed by extremism and anti-Semitism. You can find the full complement of COE’s research and publications at ADL.org. Cover: White supremacists exchange insults with counter-protesters as they attempt to guard the entrance to Emancipation Park during the ‘Unite the Right’ rally August 12, 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. -

Pepe the Frog

PEPE THE FROG: A Case Study of the Internet Meme and its Potential Subversive Power to Challenge Cultural Hegemonies by BEN PETTIS A THESIS Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Spring 2018 An Abstract of the Thesis of Ben Pettis for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the School of Journalism and Communication to be taken Spring 2018 Title: Pepe the Frog: A Case Study of the Internet Meme and Its Potential Subversive Power to Challenge Cultural Hegemonies Approved: _______________________________________ Dr. Peter Alilunas This thesis examines Internet memes, a unique medium that has the capability to easily and seamlessly transfer ideologies between groups. It argues that these media can potentially enable subcultures to challenge, and possibly overthrow, hegemonic power structures that maintain the dominance of a mainstream culture. I trace the meme from its creation by Matt Furie in 2005 to its appearance in the 2016 US Presidential Election and examine how its meaning has changed throughout its history. I define the difference between a meme instance and the meme as a whole, and conclude that the meaning of the overall meme is formed by the sum of its numerous meme instances. This structure is unique to the medium of Internet memes and is what enables subcultures to use them to easily transfer ideologies in order to challenge the hegemony of dominant cultures. Dick Hebdige provides a model by which a dominant culture can reclaim the images and symbols used by a subculture through the process of commodification. -

Spencer Sunshine*

Journal of Social Justice, Vol. 9, 2019 (© 2019) ISSN: 2164-7100 Looking Left at Antisemitism Spencer Sunshine* The question of antisemitism inside of the Left—referred to as “left antisemitism”—is a stubborn and persistent problem. And while the Right exaggerates both its depth and scope, the Left has repeatedly refused to face the issue. It is entangled in scandals about antisemitism at an increasing rate. On the Western Left, some antisemitism manifests in the form of conspiracy theories, but there is also a hegemonic refusal to acknowledge antisemitism’s existence and presence. This, in turn, is part of a larger refusal to deal with Jewish issues in general, or to engage with the Jewish community as a real entity. Debates around left antisemitism have risen in tandem with the spread of anti-Zionism inside of the Left, especially since the Second Intifada. Anti-Zionism is not, by itself, antisemitism. One can call for the Right of Return, as well as dissolving Israel as a Jewish state, without being antisemitic. But there is a Venn diagram between anti- Zionism and antisemitism, and the overlap is both significant and has many shades of grey to it. One of the main reasons the Left can’t acknowledge problems with antisemitism is that Jews persistently trouble categories, and the Left would have to rethink many things—including how it approaches anti- imperialism, nationalism of the oppressed, anti-Zionism, identity politics, populism, conspiracy theories, and critiques of finance capital—if it was to truly struggle with the question. The Left understands that white supremacy isn’t just the Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazis, but that it is part of the fabric of society, and there is no shortcut to unstitching it. -

The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right Josh Vandiver Ball State University Various source media, Political Extremism and Radicalism in the Twentieth Century EMPOWER™ RESEARCH The radical political movement known as the Alt-Right Revolution, and Evolian Traditionalism – for an is, without question, a twenty-first century American audience. phenomenon.1 As the hipster-esque ‘alt’ prefix 3. A refined and intensified gender politics, a suggests, the movement aspires to offer a youthful form of ‘ultra-masculinism.’ alternative to conservatism or the Establishment Right, a clean break and a fresh start for the new century and .2 the Millennial and ‘Z’ generations While the first has long been a feature of American political life (albeit a highly marginal one), and the second has been paralleled elsewhere on the Unlike earlier radical right movements, the Alt-Right transnational right, together the three make for an operates natively within the political medium of late unusual fusion. modernity – cyberspace – because it emerged within that medium and has been continuously shaped by its ongoing development. This operational innovation will Seminal Alt-Right figures, such as Andrew Anglin,4 continue to have far-reaching and unpredictable Richard Spencer,5 and Greg Johnson,6 have been active effects, but researchers should take care to precisely for less than a decade. While none has continuously delineate the Alt-Right’s broader uniqueness. designated the movement as ‘Alt-Right’ (including Investigating the Alt-Right’s incipient ideology – the Spencer, who coined the term), each has consistently ferment of political discourses, images, and ideas with returned to it as demarcating the ideological territory which it seeks to define itself – one finds numerous they share. -

What Is Gab? a Bastion of Free Speech Or an Alt-Right Echo Chamber?

What is Gab? A Bastion of Free Speech or an Alt-Right Echo Chamber? Savvas Zannettou Barry Bradlyn Emiliano De Cristofaro Cyprus University of Technology Princeton Center for Theoretical Science University College London [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Haewoon Kwak Michael Sirivianos Gianluca Stringhini Qatar Computing Research Institute Cyprus University of Technology University College London & Hamad Bin Khalifa University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Jeremy Blackburn University of Alabama at Birmingham [email protected] ABSTRACT ACM Reference Format: Over the past few years, a number of new “fringe” communities, Savvas Zannettou, Barry Bradlyn, Emiliano De Cristofaro, Haewoon Kwak, like 4chan or certain subreddits, have gained traction on the Web Michael Sirivianos, Gianluca Stringhini, and Jeremy Blackburn. 2018. What is Gab? A Bastion of Free Speech or an Alt-Right Echo Chamber?. In WWW at a rapid pace. However, more often than not, little is known about ’18 Companion: The 2018 Web Conference Companion, April 23–27, 2018, Lyon, how they evolve or what kind of activities they attract, despite France. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3184558. recent research has shown that they influence how false informa- 3191531 tion reaches mainstream communities. This motivates the need to monitor these communities and analyze their impact on the Web’s information ecosystem. 1 INTRODUCTION In August 2016, a new social network called Gab was created The Web’s information ecosystem is composed of multiple com- as an alternative to Twitter. -

Questioning Whiteness: “Who Is White?”

人間生活文化研究 Int J Hum Cult Stud. No. 29 2019 Questioning Whiteness: “Who is white?” ―A case study of Barbados and Trinidad― Michiru Ito1 1International Center, Otsuma Women’s University 12 Sanban-cho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan 102-8357 Key words:Whiteness, Caribbean, Barbados, Trinidad, Oral history Abstract This paper seeks to produce knowledge of identity as European-descended white in the Caribbean islands of Barbados and Trinidad, where the white populations account for 2.7% and 0.7% respectively, of the total population. Face-to-face individual interviews were conducted with 29 participants who are subjectively and objectively white, in August 2016 and February 2017 in order to obtain primary data, as a means of creating oral history. Many of the whites in Barbados recognise their interracial family background, and possess no reluctance for having interracial marriage and interracial children. They have very weak attachment to white hegemony. On contrary, white Trinidadians insist on their racial purity as white and show their disagreement towards interracial marriage and interracial children. The younger generations in both islands say white supremacy does not work anymore, yet admit they take advantage of whiteness in everyday life. The elder generation in Barbados say being white is somewhat disadvantageous, but their Trinidadian counterparts are very proud of being white which is superior form of racial identity. The paper revealed the sense of colonial superiority is rooted in the minds of whites in Barbados and Trinidad, yet the younger generations in both islands tend to deny the existence of white privilege and racism in order to assimilate into the majority of the society, which is non-white. -

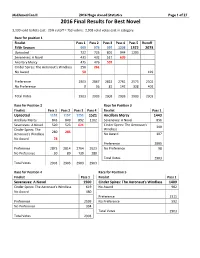

2016 Statistics Document

MidAmeriCon II 2016 Hugo Award Statistics Page 1 of 27 2016 Final Results for Best Novel 3,130 valid ballots cast. 25% cutoff = 753 voters. 2,903 valid votes cast in category. Race for position 1 Finalist Pass 1 Pass 2 Pass 3 Pass 4 Pass 5 Runoff Fifth Season 969 973 997 1208 1372 2073 Uprooted 722 725 801 944 1203 Seveneves: A Novel 431 432 517 609 Ancillary Mercy 475 476 507 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's Windlass 256 261 No Award 50 429 Preference 2903 2867 2822 2761 2575 2502 No Preference 0 36 81 142 328 401 Total Votes 2903 2903 2903 2903 2903 2903 Race for Position 2 Race for Position 3 Finalist Pass 1 Pass 2 Pass 3 Pass 4 Finalist Pass 1 Uprooted 1152 1157 1251 1521 Ancillary Mercy 1443 Ancillary Mercy 843 849 892 1102 Seveneves: A Novel 856 Seveneves: A Novel 520 523 621 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's 399 Cinder Spires: The Windlass 280 285 Aeronaut's Windlass No Award 107 No Award 78 Preference 2805 Preference 2873 2814 2764 2623 No Preference 98 No Preference 30 89 139 280 Total Votes 2903 Total Votes 2903 2903 2903 2903 Race for Position 4 Race for Position 5 Finalist Pass 1 Finalist Pass 1 Seveneves: A Novel 1500 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's Windlass 1409 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's Windlass 619 No Award 902 No Award 480 Preference 2311 Preference 2599 No Preference 592 No Preference 304 Total Votes 2903 Total Votes 2903 MidAmeriCon II 2016 Hugo Award Statistics Page 2 of 27 2016 Final Results for Best Novella 3,130 valid ballots cast. -

The Alt-Right on Campus: What Students Need to Know

THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW About the Southern Poverty Law Center The Southern Poverty Law Center is dedicated to fighting hate and bigotry and to seeking justice for the most vulnerable members of our society. Using litigation, education, and other forms of advocacy, the SPLC works toward the day when the ideals of equal justice and equal oportunity will become a reality. • • • For more information about the southern poverty law center or to obtain additional copies of this guidebook, contact [email protected] or visit www.splconcampus.org @splcenter facebook/SPLCenter facebook/SPLConcampus © 2017 Southern Poverty Law Center THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW RICHARD SPENCER IS A LEADING ALT-RIGHT SPEAKER. The Alt-Right and Extremism on Campus ocratic ideals. They claim that “white identity” is under attack by multicultural forces using “politi- An old and familiar poison is being spread on col- cal correctness” and “social justice” to undermine lege campuses these days: the idea that America white people and “their” civilization. Character- should be a country for white people. ized by heavy use of social media and memes, they Under the banner of the Alternative Right – or eschew establishment conservatism and promote “alt-right” – extremist speakers are touring colleges the goal of a white ethnostate, or homeland. and universities across the country to recruit stu- As student activists, you can counter this movement. dents to their brand of bigotry, often igniting pro- In this brochure, the Southern Poverty Law Cen- tests and making national headlines. Their appear- ances have inspired a fierce debate over free speech ter examines the alt-right, profiles its key figures and the direction of the country. -

Russian Nationalism and Ethnic Violence

Russian Nationalism and Ethnic Violence Nationalism is now the dominant narrative in Russian politics, and one with genuine popularity in society. Russian Nationalism and Ethnic Violence: Symbolic violence, lynching, pogrom, and massacre is a theoretical and empirical study which seeks to break the concept of ‘ethnic violence’ into distinguishable types, examining the key question of why violence within the same conflict takes different forms at certain times and providing empirical insight into the politics of one of the most important countries in the world today. Theoretically, the work promises to bring the content of ethnic identity back into explanations of ethnic violence, with concepts from social theory, and empirical and qualitative analysis of databases, newspaper reports, human rights reports, social media, and ethnographic interviews. It sets out a new typology of ethnic violence, studied against examples of neo-Nazi attacks, Cossack violence against Meskhetian Turks, and Russian race riots. The study brings hate crimes in Russia into the study of ethnic violence and examines the social undercurrents that have led to Putin’s embrace of nationalism. It adds to the growing body of English language scholarship on Russia’s nationalist turn in the post-Cold War era, and will be essential read- ing for anyone seeking to understand not only why different forms of ethnic violence occur, but also the potential trajectory of Russian politics in the next 20 years. Richard Arnold is Associate Professor of Political Science at Muskingum University where he teaches comparative politics and international relations. He was the 2015 recipient of the William Rainey Harper award for Out- standing Scholarship and has published numerous articles in PS: Political Science and Politics, Theoretical Criminology, Post-Soviet Affairs, Problems of Post-Communism, Nationalities Papers, and Journal for the Study of Radic- alism. -

What Role Has Social Media Played in Violence Perpetrated by Incels?

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Peace Studies Student Papers and Posters Peace Studies 5-15-2019 What Role Has Social Media Played in Violence Perpetrated by Incels? Olivia Young Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/peace_studies_student_work Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons, Social Media Commons, Social Psychology and Interaction Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Young, Olivia, "What Role Has Social Media Played in Violence Perpetrated by Incels?" (2019). Peace Studies Student Papers and Posters. 1. https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/peace_studies_student_work/1 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Peace Studies at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peace Studies Student Papers and Posters by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Peace Studies Capstone Thesis What role has social media played in violence perpetrated by Incels? Olivia Young May 15, 2019 Young, 1 INTRODUCTION This paper aims to answer the question, what role has social media played in violence perpetrated by Incels? Incels, or involuntary celibates, are members of a misogynistic online subculture that define themselves as unable to find sexual partners. Incels feel hatred for women and sexually active males stemming from their belief that women are required to give sex to them, and that they have been denied this right by women who choose alpha males over them. -

The Christchurch Attack Report: Key Takeaways on Tarrant’S Radicalization and Attack Planning

The Christchurch Attack Report: Key Takeaways on Tarrant’s Radicalization and Attack Planning Yannick Veilleux-Lepage, Chelsea Daymon and Amarnath Amarasingam i The Christchurch Attack Report: Key Takeaways on Tarrant’s Radicalization and Attack Planning Yannick Veilleux-Lepage, Chelsea Daymon and Amarnath Amarasingam ICCT Perspective December 2020 ii About ICCT The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT) is an independent think and do tank providing multidisciplinary policy advice and practical, solution- oriented implementation support on prevention and the rule of law, two vital pillars of effective counterterrorism. ICCT’s work focuses on themes at the intersection of countering violent extremism and criminal justice sector responses, as well as human rights-related aspects of counterterrorism. The major project areas concern countering violent extremism, rule of law, foreign fighters, country and regional analysis, rehabilitation, civil society engagement and victims’ voices. Functioning as a nucleus within the international counter-terrorism network, ICCT connects experts, policymakers, civil society actors and practitioners from different fields by providing a platform for productive collaboration, practical analysis, and exchange of experiences and expertise, with the ultimate aim of identifying innovative and comprehensive approaches to preventing and countering terrorism. Licensing and Distribution ICCT publications are published in open access format and distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons -

Political Trends & Dynamics

Briefing Political Trends & Dynamics The Far Right in the EU and the Western Balkans Volume 3 | 2020 POLITICAL TRENDS & DYNAMICS IN SOUTHEAST EUROPE A FES DIALOGUE SOUTHEAST EUROPE PROJECT Peace and stability initiatives represent a decades-long cornerstone of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung’s work in southeastern Europe. Recent events have only reaffirmed the centrality of Southeast European stability within the broader continental security paradigm. Both de- mocratization and socio-economic justice are intrinsic aspects of a larger progressive peace policy in the region, but so too are consistent threat assessments and efforts to prevent conflict before it erupts. Dialogue SOE aims to broaden the discourse on peace and stability in southeastern Europe and to counter the securitization of prevalent narratives by providing regular analysis that involves a comprehensive understanding of human security, including structural sources of conflict. The briefings cover fourteen countries in southeastern Europe: the seven post-Yugoslav countries and Albania, Greece, Turkey, Cyprus, Bulgaria, Romania, and Moldova. PREVIOUSLY PUBLISHED • Civic Mobilizations • The Digital Frontier in • The European Project in the Western in Southeast Europe Southeast Europe Balkans: Crisis and Transition February / March 2017 February / March 2018 Volume 2/2019 • Regional Cooperation in • Religion and Secularism • Chinese Soft Power the Western Balkans in Southeast Europe in Southeast Europe April / Mai 2017 April / May 2018 Volume 3/2019 • NATO in Southeast Europe