Question 67 - Who Was John Wycliffe?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Importance of the Reformation

Do you have a Bible in the English language in your home? Did you know that it was once illegal to own a Bible in the common language? Please take a few minutes to read this very, very brief history of Christianity. Most modern-day Christians do not know our history—but we should! The New Testament church was founded by Jesus Christ, but it has faced opposition throughout its history. In the 50 years following the death and resurrection of Jesus, most of His 12 apostles were killed for preaching the gospel of Jesus Christ. The Roman government hated Christians because they wouldn’t bow down to their false gods or to Caesar and continued to persecute and kill Christians, such as Polycarp who they martyred in 155 AD. Widespread persecution and killing of Christians continued until 313 AD, when the emperor Constantine declared Christianity to be legal. His proclamation caused most of the persecution to stop, but it also had a side effect—the church and state began to rule the people together, effectively giving birth to the Roman Catholic Church. Over time, the Roman Catholic Church gained more and more power—but unfortunately, they became corrupted by that power. They gradually began to add things to the teachings found in the Bible. For example, they began to sell indulgences to supposedly help people spend less time in purgatory. However, the idea of purgatory is not found in the Bible, and the idea that money can improve one’s favor with God shows a complete lack of understanding of the truth preached by Jesus Christ. -

Forerunners to the Reformation

{ Lecture 19 } FORERUNNERS TO THE REFORMATION * * * * * Long before Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the Wittenberg Door, there were those who recognized the corruption within the Roman Catholic Church and the need for major reform. Generally speaking, these men attempted to stay within the Catholic system rather than attempting to leave the church (as the Protestant Reformers later would do). The Waldensians (1184–1500s) • Waldo (or Peter Waldo) lived from around 1140 to 1218. He was a merchant from Lyon. But after being influenced by the story of the fourth-century Alexius (a Christian who sold all of his belongings in devotion to Christ), Waldo sold his belongings and began a life of radical service to Christ. • By 1170, Waldo had surrounded himself with a group of followers known as the Poor Men of Lyon, though they would later become known as Waldensians. • The movement was denied official sanction by the Roman Catholic Church (and condemned at the Third Lateran Council in 1179). Waldo was excommunicated by Pope Lucius III in 1184, and the movement was again condemned at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. • Waldensians were, therefore, persecuted by the Roman Catholics as heretics. However, the movement survived (even down to the present) though the Waldensians were often forced into hiding in the Alps. • The Waldensian movement was characterized by (1) voluntary poverty (though Waldo taught that salvation was not restricted to those who gave up their wealth), (2) lay preaching, and (2) the authority of the Bible (translated in the language of the people) over any other authority. -

Scope & Sequence

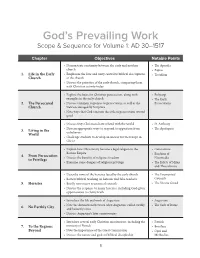

God’s Prevailing Work Scope & Sequence for Volume 1: AD 30–1517 Chapter Objectives Notable Points • Demonstrate continuity between the early and modern • The Apostles church • Papias 1. Life in the Early • Emphasize the love and unity central to biblical descriptions • Tertullian Church of the church • Discuss the priorities of the early church, comparing them with Christian activity today • Explore the basis for Christian persecution, along with • Polycarp examples in the early church • The Early 2. The Persecuted • Discuss common responses to persecution, as well as the Persecutions Church view encouraged by Scripture • Note ways that God can turn the evils of persecution toward good • Discuss ways Christians have related with the world • St. Anthony • Discern appropriate ways to respond to opposition from • The Apologists 3. Living in the unbelievers World • Challenge students to develop an answer for their hope in Christ • Explain how Christianity became a legal religion in the • Constantine Roman Empire • Eusebius of 4. From Persecution • Discuss the benefits of religious freedom Nicomedia to Privilege • Examine some dangers of religious privilege • The Edicts of Milan and Thessalonica • Describe some of the heresies faced by the early church • The Ecumenical • Review biblical teaching on heresies and false teachers Councils 5. Heresies • Briefly note major ecumenical councils • The Nicene Creed • Discuss the response to major heresies, including God-given opportunities to clarify truth • Introduce the life and work of Augustine • Augustine • Note the distinctions between what Augustine called earthly • The Sack of Rome 6. No Earthly City and heavenly cities • Discuss Augustine’s later controversies • Introduce several early Christian missionaries, including the • Patrick 7. -

What Happened in the First Century -- Creation of New Testament Writings; Spread of Christianity; Rise of Persecutions

What Happened in the First Century -- Creation of New Testament Writings; Spread of Christianity; Rise of Persecutions • The words and sayings of Jesus are collected and preserved. New Testament writings are completed. • A new generation of leaders succeeds the apostles. Nevertheless, expectation still runs high that the Lord may return at any time. The end must be close. • The Gospel taken through a great portion of the known world of the Roman empire and even to regions beyond. • New churches at first usually begin in Jewish synagogues around the empire and Christianity is seen at first as a part of Judaism. • The Church faces a major crisis in understanding itself as a universal faith and how it is to relate to its Jewish roots. • Christianity begins to emerge from its Jewish womb. A key transition takes place at the time of Jewish Revolt against Roman authority. In 70 AD Christians do not take part in the revolt and relocate to Pella in Jordan. • The Jews at Jamnia in 90 AD confirm the canon of the Hebrew Scriptures. The same books are recognized as authoritative by Christians. • Persecutions test the church. Jewish historian Josephus seems to express surprise that they are still in existence in his Antiquities in latter part of first century. • Key persecutions include Nero at Rome who blames Christians for a devastating fire that ravages the city in 64 AD He uses Christians as human torches to illumine his gardens. • Emperor Domitian demands to be worshiped as "Lord and God." During his reign the book of Revelation is written and believers cannot miss the reference when it proclaims Christ as the one worthy of our worship. -

Chronology of the Reformation 1320: John Wycliffe Is Born in Yorkshire

Chronology of the Reformation 1320: John Wycliffe is born in Yorkshire, England 1369?: Jan Hus, born in Husinec, Bohemia, early reformer and founder of Moravian Church 1384: John Wycliffe died in his parish, he and his followers made the first full English translation of the Bible 6 July 1415: Jan Hus arrested, imprisoned, tried and burned at the stake while attending the Council of Constance, followed one year later by his disciple Jerome. Both sang hymns as they died 11 November 1418: Martin V elected pope and Great Western Schism is ended 1444: Johannes Reuchlin is born, becomes the father of the study of Hebrew and Greek in Germany 21 September 1452: Girolamo Savonarola is born in Ferrara, Italy, is a Dominican friar at age 22 29 May 1453 Constantine is captured by Ottoman Turks, the end of the Byzantine Empire 1454?: Gütenberg Bible printed in Mainz, Germany by Johann Gütenberg 1463: Elector Fredrick III (the Wise) of Saxony is born (died in 1525) 1465 : Johannes Tetzel is born in Pirna, Saxony 1472: Lucas Cranach the Elder born in Kronach, later becomes court painter to Frederick the Wise 1480: Andreas Bodenstein (Karlstadt) is born, later to become a teacher at the University of Wittenberg where he became associated with Luther. Strong in his zeal, weak in judgment, he represented all the worst of the outer fringes of the Reformation 10 November 1483: Martin Luther born in Eisleben 11 November 1483: Luther baptized at St. Peter and St. Paul Church, Eisleben (St. Martin’s Day) 1 January 1484: Ulrich Zwingli the first great Swiss -

JOHN WYCLIFFE "Morning Star of the Reformation"

JOHN WYCLIFFE "Morning Star of the Reformation" The Gospel light began to shine in the 1300’s when John Wycliffe, the “Morn- ing Star of the Reformation,” began to speak out against the abuses and false teachings prevalent within the Roman Catholic Church in England. An influential teacher at Oxford, Wycliffe was expelled from his teaching position because of his outspoken stance. Wycliffe was convinced that every man, woman, and child had the right to read God’s Word in their own language. He knew that only the Scriptures could break the bondage that enslaved the people. With the help of his followers, he completed his Middle English translation in 1382 -- the first English translation of the Bible. But how to spread God’s Word? The printing press had not yet been invented, and it took 10 months for one person to copy a single Bible by hand. Wycliffe recruited a group of men that shared his passion for spreading God’s Word, and they became known as “Lollards.” Many Lollards left worldly possessions behind and embraced an ascetic life-style, setting out across England dressed in only basic clothing, a staff in one hand, and armed with an English Bible. They went to preach Christ to the common people The Roman Catholic clergy set out to destroy this movement, passing laws against the "Lollard" teaching and their Bibles. When the Lollards were caught, they were tortured and burned at the stake. A Lollard knew that when he received a Bible from John Wycliffe and was sent out to preach, he was mostly likely going to his own death. -

JOHN WYCLIFFE (1324? – 1384) a Saxon Farmer’S Son John Wycliffe A

WYCLIFFE CONTROVERSIES By: H. D. Williams, M.D., Ph.D. 1 WHAT PRECIPITATED THIS MESSAGE? • Last year, Pastor Reno and Dr. Doom spoke on translating issues and helped tweak and renew interest in the issues. • Drs. Zeinner, Stringer, Gomez, and Waite’s passion for accurate and faithful translations and the printing of them around the world. • Dr. Brown’s love for Bible history and his old Bibles. • John Doerr and Chris Pinto (Adullam Films). 2 WHAT PRECIPITATED THIS MESSAGE? • The multiple conflicting statements and controversies in articles such as: • Were Wycliffe/Purvey/Trevisa/Hereford translators of the Wycliffe Bible (or not)? • Did Wycliffe et al use Old Latin MSS (translated from the Greek RT in Northern Italy) or the Latin Vulgate? 3 WHAT PRECIPITATED THIS MESSAGE? • Did Wycliffe translate any of the Bible that goes by his name? • Was John Purvey, Wycliffe’s curate, a Jesuit, because, when he was arrested with others, his life was spared, but his Lollard ‘friends’ were killed? Or did Purvey truly recant? (Anne Hudson/Maureen Jurkowski) • Did Purvey edit the LV of the Wycliffe Bible to bring it back in line with the Latin Vulgate? Or Trevisa, or Nicholas of Hereford? • And much much more—for example, the next slide 4 Wycliffe, WYCLIFFE sending his CONTROVERSIES “Pore Preachers” to preach the Gospel. Were they Lollards, Waldensians or Wycliffites? 5 Dr. John de Wycliffe • “Princes have persecuted me without a cause: but my heart standeth in awe of thy word.” (Psalms 119:161) 6 Beginning of the Gospel of John from a pocket Wycliffe translation that may have been used by a roving Lollard preacher (late 14th century). -

John Huss and the Origins of the Protestant Reformation

Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 28/2 (2017): 97-119. Article copyright © 2017 by Trevor O’Reggio. John Huss and the Origins of the Protestant Reformation Trevor O’Reggio Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Andrews University Introduction The Protestant Reformation of the 16th century is closely associated with Martin Luther, the great German Augustinian monk, who on October 31, 1517, nailed 95 theses on the bulletin board of the castle church in Wittenberg to protest against the abuses of the indulgences and called for a debate. This event was seen by many as the spark that ignited this remarkable religious reformation. However, Matthew Spinka is more accurate when he says this event was not the beginning of the Reformation, but the result of a reform movement that began two centuries before and was particularly effective during the conciliar period.1 During the prior two centuries before Luther called for a debate on the indulgence issue, and his eventual revolt against the church, there were many voices within the Roman Catholic Church who saw the deplorable conditions of the church and called for reform. Time and time again their voices were silenced. They were condemned as heretics and many were executed. But no sooner than their voices were silenced, others were raised up, calling for reformation. Most notable among these voices were the English philosopher/professor John Wycliffe at Oxford University in England, Girolamo Savonarola, the charismatic priest at Florence, Italy and 1 For a description of highlights of this reformatory movement see Matthew Spinka, ed. and trans John Huss at the Council of Constance (New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1965), 3-86. -

1 the Great Controversy Series 10 John Huss and Jerome: Martyrs For

The Great Controversy Series 10 John Huss and Jerome: Martyrs for the Truth Mark 13:19-20 "For in those days there will be tribulation, such as has not been since the beginning of the creation which God created until this time, nor ever shall be. 20 "And unless the Lord had shortened those days, no flesh would be saved; but for the elect's sake, whom He chose, He shortened the days. In the period of papal supremacy from 538 to 1798, believers were persecuted and tortured because they believed and practiced something different than what the Catholic Church taught. Because the Bible was prohibited from place to place the people were left in darkness. Those who sought light read their Bibles and worshipped secretly. When caught, these people were thrown in jail and martyred. Millions of people thus lost their lives. This was the time of tribulation that Jesus spoke about. But Jesus said that those day would be shortened. How would that period be shortened? The Protestant Reformation was one of the means that the Lord would use. The Protestant Reformation did not burst on the scene suddenly. For centuries there were pioneer reformers. We talked about the Waldenses. John Wycliffe was the Morning Star of the Reformation. John Wycliffe’s writings and ideas extended beyond the borders of England. They went to far away countries. The king of Bohemia Wenzel IV’s sister Anna, after her marriage with King Richard II of England, Bohemian nobles who studied at Oxford, began to bring John Wycliffe’s writings to Prague. -

John Wycliffe, England, Theologian

John Wycliffe, England, Theologian May 22. John Wycliffe. Wycliffe was a Protestant long before there were Protestants. The Protestant Reformation is a 16th century phenomenon, but Wycliffe lived in the 14th century. Two-hundred years before Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the castle door, Wycliffe wrote and circulated 18 Theses, including outright challenges to the Catholic church’s authority. (Wycliff said their authority was second to the Scriptures.) Obviously, his ideas got him in trouble with the Catholic Church, and on this date in 1377, Pope Gregory XI issued 5 public decrees against Wycliffe denouncing his 18 Theses as “erroneous and dangerous to Church and State.” Wycliffe pointed out that Moses learned God’s law in his own language (Hebrew), and the Apostles learned it in their own language (Greek). Even the contemporary very rich could read it in Latin. But ordinary people had no translation they could read. Wycliffe set out to change that, and directed the production of Bibles handwritten in Middle English—at least fifty years before the invention of the Gutenberg printing press. Here’s his story. Flattery means nothing to a man determined to obey God. John Wycliffe spent most of his life standing up against the church’s hypocrisy. Over the decades, he had seen friars take advantage of the poor, kidnap young people and force them into ministry, and call preaching the gospel outside of religious places heresy. John had just finished a work calling for the Bible to be translated into English. Regular people had been starved of the Word of God. -

Protests to Reform the Catholic Church

The Reformation Protests to Reform the Catholic Church WhyWhatWhy would is do the youthe man thinkseeChurch tied? here? the order man thedid toexecution receive suchof certain a harsh individuals? punishment? In the late 1300’s, John Wycliffe, a scholar at Oxford University in England, questioned the authority of Church teachings. This is after the Great Schism. Wycliffe felt that Church corruption limited the ability of the clergy to properly lead Christians to salvation. What do you think? Wycliffe stated that a person did not need the Church or its sacraments to attain salvation. He said that Christians should regard the Bible, not the Church, as the supreme source of religious authority. In order to aid his fellow Englishmen to read the Bible, he translated it into English. Wycliffe was expelled from Oxford University in 1382 for his reformist ideas. His ideas, however, spread across Europe and influenced other reformers. Notes: The Reformation: Early Calls for Reform Who were some of the first people to speak out against Church corruption and teachings? John Wycliffe of England (1382): • He thought Christians didn’t need Church or sacraments to achieve salvation. • He regarded the Bible as the most important source of religious authority. • He completed the first translation of the Bible into English. • Outcome: He was expelled from Oxford. Jan Huss was influenced by the ideas of John Wycliffe. In 1403, Huss was the rector of Prague University. It was in this capacity that he challenged the pope’s authority and criticized the wealth of the Church. Huss believed that everyone should have access to God, without necessarily having to go through the Church. -

John Wycliffe's Religious Doctrines GORDONLEFF

John Wycliffe's Religious Doctrines GORDONLEFF John Wycliffe was the major English Reformer of the Middle Ages. But he was not the 'Morning Star' of the Reformation if by that is meant its direct forerunner. Wycliffe's voice, for all its distinctive ness, was not a lone voice; and its advocacy was less of new doctrines or institutional forms than of spiritual renewal by a return to first apostolic principles exemplified in Christ's life and teachings. Moreover, Wycliffe's main influence was felt not among his Lollard followers in England, even if they did continue into the sixteenth century, but upon John Hus and his followers in Bohemia, where the demand for religious reform fused with the demand for political independence into a wider movement. Wycliffe's outlook is best understood as a highly individual, often idiosyncratic, development of what may be called an apostolic view of Christian truth, going back, in the form in which he received it, to the apostolic groups of the early twelfth century. 1 It took its inspiration from the image of Christ, derived from the Bible, of a possessionless, homeless wanderer, renouncing all dominion over men and things, and devoting himself to preaching salvation and spiritual ministra tion. His life, and that of his disciples, were the norm for all Christians, above all those in priestly orders, from the pope downwards. True Christian discipleship therefore meant a church without temporalities or jurisdiction, and a priesthood distinguished solely by its spiritual qualities of life in emulating Christ's life of temporal renunciation and preaching the gospel.