The Logic of Reformation: the Metaphysical Basis of John Wyclif's Theology" (2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Importance of the Reformation

Do you have a Bible in the English language in your home? Did you know that it was once illegal to own a Bible in the common language? Please take a few minutes to read this very, very brief history of Christianity. Most modern-day Christians do not know our history—but we should! The New Testament church was founded by Jesus Christ, but it has faced opposition throughout its history. In the 50 years following the death and resurrection of Jesus, most of His 12 apostles were killed for preaching the gospel of Jesus Christ. The Roman government hated Christians because they wouldn’t bow down to their false gods or to Caesar and continued to persecute and kill Christians, such as Polycarp who they martyred in 155 AD. Widespread persecution and killing of Christians continued until 313 AD, when the emperor Constantine declared Christianity to be legal. His proclamation caused most of the persecution to stop, but it also had a side effect—the church and state began to rule the people together, effectively giving birth to the Roman Catholic Church. Over time, the Roman Catholic Church gained more and more power—but unfortunately, they became corrupted by that power. They gradually began to add things to the teachings found in the Bible. For example, they began to sell indulgences to supposedly help people spend less time in purgatory. However, the idea of purgatory is not found in the Bible, and the idea that money can improve one’s favor with God shows a complete lack of understanding of the truth preached by Jesus Christ. -

Promoting a New Synthesis of Fa Ith and Reason

March • April 2008 • Volume 40 • Number 2 Body and Soul – Rediscovering Catholic Orthodoxy AND SYNTHESIS NEW PROMOTING A Editorial Aquinas on the Subsistent Soul Kevin Flannery The Soul: Aquinas contra some Thomists et al REASON Francis Selman The Goodness of the Human Body Jeffrey Kirby OF Our regular features Diagnosis The soul and Pullman’s influence: The Truth Will Set You Free FAITH FAITH Shared shock at episcopal teaching: Comment on the Comments Prospects for heterodoxy: Notes from across the Atlantic Debate The value of discussing God and the soul: Road from Regensburg The nature of science: Cutting Edge Letting go of catholicity at a Catholic hospital: Other Angles Also Price: £4 Reviewing Newman: Bishop Philip Boyce Post-modernism: Margeurite Peeters and Letters Fit for Mission? What next?: William Oddie, James Arthur and the Editor www.faith.org.uk MAY PRICE INCREASE Due to further increases in costs regrettably annual faith we will be increasing the basic subscription rate to £25 and the cover price to £4.50 for the May summer session issue. Other rates will increase accordingly. We hope you will still find our full, frank and quality content very good value for money. Thank you for your continued support of our apostolate. Catholicism a new synthesis by Edward Holloway Monday 4th to Friday 8th August 2008 Pope John Paul II gave the blueprint for at Woldingham School catechetical renewal with the Catechism of the Catholic Church. Catholicism: A New Synthesis Four days of lectures, discussion seeks to show why such teaching makes perfect and seminars around a particular theme, sense in a world which has come of age in in a relaxed holiday environment, scientific understanding. -

Forerunners to the Reformation

{ Lecture 19 } FORERUNNERS TO THE REFORMATION * * * * * Long before Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the Wittenberg Door, there were those who recognized the corruption within the Roman Catholic Church and the need for major reform. Generally speaking, these men attempted to stay within the Catholic system rather than attempting to leave the church (as the Protestant Reformers later would do). The Waldensians (1184–1500s) • Waldo (or Peter Waldo) lived from around 1140 to 1218. He was a merchant from Lyon. But after being influenced by the story of the fourth-century Alexius (a Christian who sold all of his belongings in devotion to Christ), Waldo sold his belongings and began a life of radical service to Christ. • By 1170, Waldo had surrounded himself with a group of followers known as the Poor Men of Lyon, though they would later become known as Waldensians. • The movement was denied official sanction by the Roman Catholic Church (and condemned at the Third Lateran Council in 1179). Waldo was excommunicated by Pope Lucius III in 1184, and the movement was again condemned at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. • Waldensians were, therefore, persecuted by the Roman Catholics as heretics. However, the movement survived (even down to the present) though the Waldensians were often forced into hiding in the Alps. • The Waldensian movement was characterized by (1) voluntary poverty (though Waldo taught that salvation was not restricted to those who gave up their wealth), (2) lay preaching, and (2) the authority of the Bible (translated in the language of the people) over any other authority. -

Inside the Epistemological Cave All Bets Are

Inside the epistemological cave all bets are off Colin Wight Department of Politics, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, The University of Exeter, The Queen’s Drive, Exeter, Devon EX4 4QJ, UK. E-mail: [email protected] In this short rejoinder to Friedrich Kratochwil’s plea for a ‘pragmatic approach to theory building’, I argue that, despite his claims to the contrary, his position essentially rests on a curious form of foundationalism and relativism. The problem, as I identify it, is that Kratochwil’s attempt to move contemporary debate forward fails because he treats the issue only in epistemological terms. Kratochwil is deeply suspicious of the very idea of the ‘real world’and reduces it to an infinitely malleable construct of our ways of thinking and talking about it. This means that he remains trapped in the epistemological cave and is condemned to an endless quest to solve problems that have no solution. But the real world is not simply something that we think and talk about but, rather, we engage with it in practice and as such it offers resistance to our attempts to grasp it. Hence, it is not a subject without a voice in the global conversation. This is an important theoretical limit, particularly in relation to contemporary issues surrounding global environmental problems. Journal of International Relations and Development (2007) 10, 40–56. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jird.1800109 Keywords: dogmatism epistemology; foundationalism; reality; relativism; theoretical pluralism; truth Introduction When, in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, the prisoner released from his chains returns to inform his fellow inmates that he has discovered that their world is an illusion, he could be forgiven for being surprised by their response. -

The Power of Principles: Physics Revealed

The Passions of Logic: Appreciating Analytic Philosophy A CONVERSATION WITH Scott Soames This eBook is based on a conversation between Scott Soames of University of Southern California (USC) and Howard Burton that took place on September 18, 2014. Chapters 4a, 5a, and 7a are not included in the video version. Edited by Howard Burton Open Agenda Publishing © 2015. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Biography 4 Introductory Essay The Utility of Philosophy 6 The Conversation 1. Analytic Sociology 9 2. Mathematical Underpinnings 15 3. What is Logic? 20 4. Creating Modernity 23 4a. Understanding Language 27 5. Stumbling Blocks 30 5a. Re-examining Information 33 6. Legal Applications 38 7. Changing the Culture 44 7a. Gödelian Challenges 47 Questions for Discussion 52 Topics for Further Investigation 55 Ideas Roadshow • Scott Soames • The Passions of Logic Biography Scott Soames is Distinguished Professor of Philosophy and Director of the School of Philosophy at the University of Southern California (USC). Following his BA from Stanford University (1968) and Ph.D. from M.I.T. (1976), Scott held professorships at Yale (1976-1980) and Princeton (1980-204), before moving to USC in 2004. Scott’s numerous awards and fellowships include USC’s Albert S. Raubenheimer Award, a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foun- dation Fellowship, Princeton University’s Class of 1936 Bicentennial Preceptorship and a National Endowment for the Humanities Research Fellowship. His visiting positions include University of Washington, City University of New York and the Catholic Pontifical University of Peru. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2010. In addition to a wide array of peer-reviewed articles, Scott has authored or co-authored numerous books, including Rethinking Language, Mind and Meaning (Carl G. -

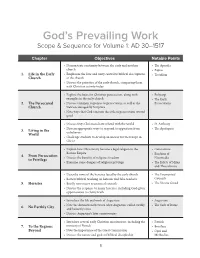

Scope & Sequence

God’s Prevailing Work Scope & Sequence for Volume 1: AD 30–1517 Chapter Objectives Notable Points • Demonstrate continuity between the early and modern • The Apostles church • Papias 1. Life in the Early • Emphasize the love and unity central to biblical descriptions • Tertullian Church of the church • Discuss the priorities of the early church, comparing them with Christian activity today • Explore the basis for Christian persecution, along with • Polycarp examples in the early church • The Early 2. The Persecuted • Discuss common responses to persecution, as well as the Persecutions Church view encouraged by Scripture • Note ways that God can turn the evils of persecution toward good • Discuss ways Christians have related with the world • St. Anthony • Discern appropriate ways to respond to opposition from • The Apologists 3. Living in the unbelievers World • Challenge students to develop an answer for their hope in Christ • Explain how Christianity became a legal religion in the • Constantine Roman Empire • Eusebius of 4. From Persecution • Discuss the benefits of religious freedom Nicomedia to Privilege • Examine some dangers of religious privilege • The Edicts of Milan and Thessalonica • Describe some of the heresies faced by the early church • The Ecumenical • Review biblical teaching on heresies and false teachers Councils 5. Heresies • Briefly note major ecumenical councils • The Nicene Creed • Discuss the response to major heresies, including God-given opportunities to clarify truth • Introduce the life and work of Augustine • Augustine • Note the distinctions between what Augustine called earthly • The Sack of Rome 6. No Earthly City and heavenly cities • Discuss Augustine’s later controversies • Introduce several early Christian missionaries, including the • Patrick 7. -

What Happened in the First Century -- Creation of New Testament Writings; Spread of Christianity; Rise of Persecutions

What Happened in the First Century -- Creation of New Testament Writings; Spread of Christianity; Rise of Persecutions • The words and sayings of Jesus are collected and preserved. New Testament writings are completed. • A new generation of leaders succeeds the apostles. Nevertheless, expectation still runs high that the Lord may return at any time. The end must be close. • The Gospel taken through a great portion of the known world of the Roman empire and even to regions beyond. • New churches at first usually begin in Jewish synagogues around the empire and Christianity is seen at first as a part of Judaism. • The Church faces a major crisis in understanding itself as a universal faith and how it is to relate to its Jewish roots. • Christianity begins to emerge from its Jewish womb. A key transition takes place at the time of Jewish Revolt against Roman authority. In 70 AD Christians do not take part in the revolt and relocate to Pella in Jordan. • The Jews at Jamnia in 90 AD confirm the canon of the Hebrew Scriptures. The same books are recognized as authoritative by Christians. • Persecutions test the church. Jewish historian Josephus seems to express surprise that they are still in existence in his Antiquities in latter part of first century. • Key persecutions include Nero at Rome who blames Christians for a devastating fire that ravages the city in 64 AD He uses Christians as human torches to illumine his gardens. • Emperor Domitian demands to be worshiped as "Lord and God." During his reign the book of Revelation is written and believers cannot miss the reference when it proclaims Christ as the one worthy of our worship. -

Leibniz and China: a Commerce of Light Franklin Perkins Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-83024-9 - Leibniz and China: A Commerce of Light Franklin Perkins Frontmatter More information LEIBNIZ AND CHINA Why was Leibniz so fascinated by Chinese philosophy and culture? What specific forms did his interest take? How did his interest com- pare with the relative indifference of his philosophical contemporaries and near-contemporaries such as Spinoza and Locke? In this highly original book, Franklin Perkins examines Leibniz’s voluminous writ- ings on the subject and suggests that his interest was founded in his own philosophy: the nature of his metaphysical and theological views required him to take Chinese thought seriously. Leibniz was unusual in holding enlightened views about the intellectual profitability of cultural exchange, and in a broad-ranging discussion Perkins charts these views, their historical context, and their social and philosophical ramifications. The result is an illuminating philosophical study which also raises wider questions about the perils and rewards of trying to understand and learn from a different culture. franklin perkins is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at DePaul University, Chicago. He has published in early modern European philosophy, early Chinese philosophy, and comparative philosophy, with articles appearing in the Journal of the History of Ideas, the Journal of Chinese Philosophy, and the Leibniz Review. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-83024-9 - Leibniz and China: A Commerce of Light -

A New History of Western Philosophy Ebook Free Download

A NEW HISTORY OF WESTERN PHILOSOPHY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anthony Kenny | 1088 pages | 15 Oct 2012 | Oxford University Press | 9780199656493 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom A New History of Western Philosophy PDF Book Namespaces Article Talk. Politics Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. It is obvious that they This approach leads to a thoroughly engaging overview for anyone interested in Western philosophy. Choose your country or region Close. Many more analytically-minded philosophers are unlikely to be very familiar with the views of Schopenhauer, and many of any stripe tend not to be up on the sometimes very odd details of Peirce's views. Schools of Thought: From Aristotle to Augustine 3. Sign in to Purchase Instantly. Philosophy Break is a social enterprise dedicated to getting more people engaged with philosophy. Politics Though critics claim Kenny's account of philosophy, while generally good, is quite limited in the Islamic world, focusing only on those works that became important in the Latin tradition. The title of the first chapter -- "Bentham to Nietzsche" -- is indicative of this cosmopolitan approach, as is the inclusion of thinkers as diverse as Schopenhauer and Mill in one chapter. Follow Philosophy Break. God Chronology. He has published more than forty books on philosophy and history. A New History of Western Philosophy is a stimulating chronicle of the intellectual development of Western civilization, allowing readers to trace the birth and growth of philosophy from antiquity to the present day. Knowledge and its Limits 5. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Pluralism and Realism Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2n611357 Author Evpak, Matthew Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Pluralism and Realism A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy by Matthew Evpak Committee in charge: Professor Gila Sher, Chair Professor Samuel Buss Professor Andrew Kehler Professor Donald Rutherford Professor Clinton Tolley 2018 The Dissertation of Matthew Evpak is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _____________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California San Diego 2018 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ............................................................................................................................................................................................................ iii Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Historical Essays in Philosophy by Anthony Kenny Owen Goldin Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Philosophy Faculty Research and Publications Philosophy, Department of 1-1-2009 Review of From Empedocles to Wittgenstein: Historical Essays in Philosophy by Anthony Kenny Owen Goldin Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, Vol. 3, No. 9 (2009). Permalink. © 2009 University of Notre Dame Philosophy Department. Used with permission. Anthony Kenny From Empedocles to Wittgenstein: Historical Essays in Philosophy Anthony Kenny, From Empedocles to Wittgenstein: Historical Essays in Philosophy, Oxford University Press, 2008, 218pp., $60.00 (hbk), ISBN 9780199550821. Reviewed by Owen Goldin, Marquette University From Empedocles to Wittgenstein is a collection of essays written by Kenny during the last few years. In his preface Kenny tells us that most are attempts to justify somewhat controversial positions taken in his introductory A New History of Western Philosophy.[1] Most, but not all, have been previously published; some have been revised for this collection. As the title declares, all have their source in issues in the history of philosophy. Together they document the most recent phase in the evolution of the thought of one of the most significant philosophers working today. "Seven Concepts in Creation" offers a synoptic view of the philosophic contours of what Kenny identifies as the seven major concepts of creation found in the Western tradition: "the Platonic concept, the Mosaic concept, the Augustinian concept, the Avicennan concept, the Thomist concept, the Scotist concept, and the Cartesian concept" (12). Kenny presents a taxonomy of these by way of seven aspects of those accounts: what they say of the nature of the creator, what existed prior to creation, whether there was a blueprint for creation (and if so, what it was), the reason for creation, the things created, and when creation took place. -

Fundamentalism Themenheft 8

Themenheft 8 Herbert Rainer Pelikan Fundamentalism Themenheft 8 Herbert Rainer Pelikan Fundamentalism Extreme Tendencies in modern Christianity, Islam and Judaism (= Evang. Rundbrief, SNr. 1/2003) Wien 2003 Vorwort Der Begriff Fundamentalismus ist ein Thema der aktuellen Diskussion; Grund genug, sich damit auch aus ethischer Sicht zu beschäftigen. Fundamentalismus, der sich nach der iranischen Ayatollah-Revolution (1979) verbreite- te, ist heute fast ein Schimpfwort geworden. Fundamentalismus ist keineswegs ein speziell christliches oder islamisches Phänomen, son- dern die Gefahr einer jeden - auch säkularen - Weltanschauung und Religion. Anstelle eines vertrauenden und Wachstumsfähigen Glaubens wird ein absoluter und endgültiger Wahrheits- standpunkt bezogen, der nicht in der Diskussion einsichtig gemacht, sondern nur mit Macht behauptet wird. Fundamentalismus ist ein sehr ambivalentes Thema. Denn grundsätzlich ist es ja zu begrüßen, wenn Menschen ihr Leben auf einem festen Funda- ment aufbauen. Das gilt ja auch für den Glauben, wie das Gleichnis Jesu Vom Hausbau (Mt. 7, 24-29) sehr deutlich zeigt: 24 Darum, wer diese meine Rede hört und tut sie, der gleicht einem klugen Mann, der sein Haus auf Fels baute. 25 Als nun ein Platzregen fiel und die Wasser kamen und die Winde wehten und stießen an das Haus, fiel es doch nicht ein; denn es war auf Fels gegrün- det. 26 Und wer diese meine Rede hört und tut sie nicht, der gleicht einem törichten Mann, der sein Haus auf Sand baute. 27 Als nun ein Platzregen fiel und die Wasser kamen und die Winde wehten und stießen an das Haus, da fiel es ein und sein Fall war groß. Ins Politische übertragen könnte man hier von einem Hochhalten einer Werteorientierung in positiver Abgrenzung gegenüber einem Opportunismus sprechen.