John Wycliffe's Religious Doctrines GORDONLEFF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

God and Moral Humans in Leviathan, Book

God and the moral beings –A contextual study of Thomas Hobbes’s third book in Leviathan Samuel Andersson Extended Essay C, Spring Term 2007 Department of History of Science and Ideas Uppsala University Abstract Samuel Andersson, God and the moral beings –A contextual study of Thomas Hobbes’s third book in Leviathan. Uppsala University: Department of History of Science and Ideas, Extended Essay C, Spring Term, 2007. The question this essay sets out to answer is what role God plays in Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan, in the book “Of a Christian Common-wealth”, in relationship to humans as moral beings. The question is relevant as the religious aspects of Hobbes’s thinking cannot be ignored, although Hobbes most likely had rather secular and sceptical philosophical views. In order to answer the research question Leviathan’s “Of a Christian Common-wealth” will be compared and contrasted with two contextual works: the canonical theological document of the Anglican Church, the Thirty-Nine Articles (1571), and Presbyterian-Anglican document the Westminster Confession (1648). Also, recent scholarly works on Hobbes and more general reference works will be employed and discussed. Hobbes’s views provide a seemingly unsolvable paradox. On the one hand, God is either portrayed, or becomes by consequence of his sceptical and secular state thinking, a distant God in relationship to moral humans in “Of a Christian Common-wealth”. Also, the freedom humans seem to have in making their own moral decisions, whether based on natural and divine, or positive laws, appears to obscure God’s almightiness. On the other hand, when placing Hobbes in context, Hobbes appears to have espoused Calvinist views, with beliefs in predestination and that God is the cause of everything. -

Importance of the Reformation

Do you have a Bible in the English language in your home? Did you know that it was once illegal to own a Bible in the common language? Please take a few minutes to read this very, very brief history of Christianity. Most modern-day Christians do not know our history—but we should! The New Testament church was founded by Jesus Christ, but it has faced opposition throughout its history. In the 50 years following the death and resurrection of Jesus, most of His 12 apostles were killed for preaching the gospel of Jesus Christ. The Roman government hated Christians because they wouldn’t bow down to their false gods or to Caesar and continued to persecute and kill Christians, such as Polycarp who they martyred in 155 AD. Widespread persecution and killing of Christians continued until 313 AD, when the emperor Constantine declared Christianity to be legal. His proclamation caused most of the persecution to stop, but it also had a side effect—the church and state began to rule the people together, effectively giving birth to the Roman Catholic Church. Over time, the Roman Catholic Church gained more and more power—but unfortunately, they became corrupted by that power. They gradually began to add things to the teachings found in the Bible. For example, they began to sell indulgences to supposedly help people spend less time in purgatory. However, the idea of purgatory is not found in the Bible, and the idea that money can improve one’s favor with God shows a complete lack of understanding of the truth preached by Jesus Christ. -

Forerunners to the Reformation

{ Lecture 19 } FORERUNNERS TO THE REFORMATION * * * * * Long before Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the Wittenberg Door, there were those who recognized the corruption within the Roman Catholic Church and the need for major reform. Generally speaking, these men attempted to stay within the Catholic system rather than attempting to leave the church (as the Protestant Reformers later would do). The Waldensians (1184–1500s) • Waldo (or Peter Waldo) lived from around 1140 to 1218. He was a merchant from Lyon. But after being influenced by the story of the fourth-century Alexius (a Christian who sold all of his belongings in devotion to Christ), Waldo sold his belongings and began a life of radical service to Christ. • By 1170, Waldo had surrounded himself with a group of followers known as the Poor Men of Lyon, though they would later become known as Waldensians. • The movement was denied official sanction by the Roman Catholic Church (and condemned at the Third Lateran Council in 1179). Waldo was excommunicated by Pope Lucius III in 1184, and the movement was again condemned at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. • Waldensians were, therefore, persecuted by the Roman Catholics as heretics. However, the movement survived (even down to the present) though the Waldensians were often forced into hiding in the Alps. • The Waldensian movement was characterized by (1) voluntary poverty (though Waldo taught that salvation was not restricted to those who gave up their wealth), (2) lay preaching, and (2) the authority of the Bible (translated in the language of the people) over any other authority. -

Apologetics Study Guide Week 5 Week 5: WHAT to DO with HELL?

Apologetics Study Guide Week 5 Week 5: WHAT TO DO WITH HELL? Opening Question: What have you heard about hell from sermons, if anything? What are some depictions of hell that you are familiar with (e.g. art, pop culture, etc.?) What questions come up in your mind when you think about hell? We will engage the topic of hell by asking a few questions: 1. Is hell real? 2. Why is there a hell? Who goes there? 3. What is all this about predestination? Oftentimes, we think of hell like this: God gives humans time to choose God, but if they do not, then he casts them into hell; and even if those people beg for mercy, God says, “Nope! You had your chance!” Thankfully, that is not the biblical depiction of hell or of how God relates to people.1 Every human has a sinful, fallen nature. No one is free from sin, and we cannot freely turn back to God on our own. We are all deserving of death, of hell, eternal separation from God. If we were left to ourselves, we would never choose God—we would not know to choose God, because we are so mired in self and sin. It is only by the work of the Holy Spirit that we are drawn to God in Jesus Christ where we find salvation and restoration of our relationship to God. God makes the first move and chooses and saves people.2 God chooses people so that they may tell others about God and God’s grace. -

Predestination – a Christian’S Hope Or God’S Unfairness?

Melanesian Journal of Theology 11-1&2 (1995) PREDESTINATION – A CHRISTIAN’S HOPE OR GOD’S UNFAIRNESS? Gabriel Keni Introduction This is God’s eternal purpose of deliverance of those He has chosen through Jesus Christ. The doctrine of predestination is one that brings several questions to the minds of Christians. These questions sometimes affect our whole attitude to life and salvation, and towards our trust and joy in God. But the doctrine of predestination is simple to state. It is eternity. God has chosen some for salvation through Christ, but has left others to their own choice of rebellion against Him. On some, He has mercy, drawing them to Christ; others He has hardened, and blinded by Satan, whose plans they willingly fulfil. The basic concept of Christian faith is that God is gracious, as clearly revealed in the Old Testament (Ex 34:6-7). The love of God is the motive for salvation, since God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son (John 3:16). The Bible teaches clearly, and common sense confirms, that God is sovereign over all aspects of His creation and their characteristics. He is also sovereign over death, so that He can bring back from death to life. We are, by nature, children of wrath, under God’s eternal condemnation of death. The dead cannot save themselves, but a way is open through Jesus Christ, so we must be born by God’s power of His Spirit. The doctrine of predestination is simply the consequence of man’s nature (death in trespasses and sins), and of God’s nature (His goodness and mercy). -

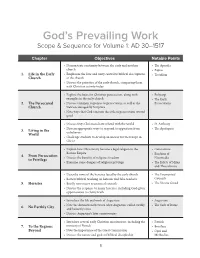

Scope & Sequence

God’s Prevailing Work Scope & Sequence for Volume 1: AD 30–1517 Chapter Objectives Notable Points • Demonstrate continuity between the early and modern • The Apostles church • Papias 1. Life in the Early • Emphasize the love and unity central to biblical descriptions • Tertullian Church of the church • Discuss the priorities of the early church, comparing them with Christian activity today • Explore the basis for Christian persecution, along with • Polycarp examples in the early church • The Early 2. The Persecuted • Discuss common responses to persecution, as well as the Persecutions Church view encouraged by Scripture • Note ways that God can turn the evils of persecution toward good • Discuss ways Christians have related with the world • St. Anthony • Discern appropriate ways to respond to opposition from • The Apologists 3. Living in the unbelievers World • Challenge students to develop an answer for their hope in Christ • Explain how Christianity became a legal religion in the • Constantine Roman Empire • Eusebius of 4. From Persecution • Discuss the benefits of religious freedom Nicomedia to Privilege • Examine some dangers of religious privilege • The Edicts of Milan and Thessalonica • Describe some of the heresies faced by the early church • The Ecumenical • Review biblical teaching on heresies and false teachers Councils 5. Heresies • Briefly note major ecumenical councils • The Nicene Creed • Discuss the response to major heresies, including God-given opportunities to clarify truth • Introduce the life and work of Augustine • Augustine • Note the distinctions between what Augustine called earthly • The Sack of Rome 6. No Earthly City and heavenly cities • Discuss Augustine’s later controversies • Introduce several early Christian missionaries, including the • Patrick 7. -

What Happened in the First Century -- Creation of New Testament Writings; Spread of Christianity; Rise of Persecutions

What Happened in the First Century -- Creation of New Testament Writings; Spread of Christianity; Rise of Persecutions • The words and sayings of Jesus are collected and preserved. New Testament writings are completed. • A new generation of leaders succeeds the apostles. Nevertheless, expectation still runs high that the Lord may return at any time. The end must be close. • The Gospel taken through a great portion of the known world of the Roman empire and even to regions beyond. • New churches at first usually begin in Jewish synagogues around the empire and Christianity is seen at first as a part of Judaism. • The Church faces a major crisis in understanding itself as a universal faith and how it is to relate to its Jewish roots. • Christianity begins to emerge from its Jewish womb. A key transition takes place at the time of Jewish Revolt against Roman authority. In 70 AD Christians do not take part in the revolt and relocate to Pella in Jordan. • The Jews at Jamnia in 90 AD confirm the canon of the Hebrew Scriptures. The same books are recognized as authoritative by Christians. • Persecutions test the church. Jewish historian Josephus seems to express surprise that they are still in existence in his Antiquities in latter part of first century. • Key persecutions include Nero at Rome who blames Christians for a devastating fire that ravages the city in 64 AD He uses Christians as human torches to illumine his gardens. • Emperor Domitian demands to be worshiped as "Lord and God." During his reign the book of Revelation is written and believers cannot miss the reference when it proclaims Christ as the one worthy of our worship. -

Chronology of the Reformation 1320: John Wycliffe Is Born in Yorkshire

Chronology of the Reformation 1320: John Wycliffe is born in Yorkshire, England 1369?: Jan Hus, born in Husinec, Bohemia, early reformer and founder of Moravian Church 1384: John Wycliffe died in his parish, he and his followers made the first full English translation of the Bible 6 July 1415: Jan Hus arrested, imprisoned, tried and burned at the stake while attending the Council of Constance, followed one year later by his disciple Jerome. Both sang hymns as they died 11 November 1418: Martin V elected pope and Great Western Schism is ended 1444: Johannes Reuchlin is born, becomes the father of the study of Hebrew and Greek in Germany 21 September 1452: Girolamo Savonarola is born in Ferrara, Italy, is a Dominican friar at age 22 29 May 1453 Constantine is captured by Ottoman Turks, the end of the Byzantine Empire 1454?: Gütenberg Bible printed in Mainz, Germany by Johann Gütenberg 1463: Elector Fredrick III (the Wise) of Saxony is born (died in 1525) 1465 : Johannes Tetzel is born in Pirna, Saxony 1472: Lucas Cranach the Elder born in Kronach, later becomes court painter to Frederick the Wise 1480: Andreas Bodenstein (Karlstadt) is born, later to become a teacher at the University of Wittenberg where he became associated with Luther. Strong in his zeal, weak in judgment, he represented all the worst of the outer fringes of the Reformation 10 November 1483: Martin Luther born in Eisleben 11 November 1483: Luther baptized at St. Peter and St. Paul Church, Eisleben (St. Martin’s Day) 1 January 1484: Ulrich Zwingli the first great Swiss -

PREDESTINATION" (Romans 9:1-33) (Chuck Swindoll)

"PREDESTINATION" (Romans 9:1-33) (Chuck Swindoll) Predestination. Just the word appears intimidating. It is perhaps one of the most difficult concepts in all of Christian doctrine because it appears on the surface to rob humans of their most precious treasure: their autonomy. Although the doctrine challenges our notions of self- determination, it is ultimately what separates Christians from humanists, who proclaim that the fate of the world is ours to decide. The past, they say, has been fired in the kiln of history and cannot be altered, but tomorrow is still soft and pliable clay, ready to be shaped by the hands of humanity. Individually and collectively, we—not an almighty figment of wishful thinking—will determine our own future. Put in today's terms, "It's all about us." Today, I stand in the company of great theologians, preachers, teachers, missionaries, and evangelists to proclaim exactly the opposite. I join the ranks of reformers like William Tyndale, John Wycliffe, John Calvin, Huldrych Zwingli, John Huss, John Knox, and Martin Luther. I sing with the poets Isaac Watts and John Newton and preach with George Whitefield, Jonathan Edwards, and Charles Spurgeon. I respond to the call of pioneer missionary William Carey, who stirred his slumbering Calvinist generation to follow the command of Christ and make disciples of all nations. I place my theology alongside those of John Owen, A. H. Strong, William Shedd, Charles Hodge, B. B. Warfield, Lewis Sperry Chafer, John F. Walvoord, Donald Grey Barnhouse, and Ray Stedman. And I am numbered alongside my contemporaries John Stott, R. -

JOHN WYCLIFFE "Morning Star of the Reformation"

JOHN WYCLIFFE "Morning Star of the Reformation" The Gospel light began to shine in the 1300’s when John Wycliffe, the “Morn- ing Star of the Reformation,” began to speak out against the abuses and false teachings prevalent within the Roman Catholic Church in England. An influential teacher at Oxford, Wycliffe was expelled from his teaching position because of his outspoken stance. Wycliffe was convinced that every man, woman, and child had the right to read God’s Word in their own language. He knew that only the Scriptures could break the bondage that enslaved the people. With the help of his followers, he completed his Middle English translation in 1382 -- the first English translation of the Bible. But how to spread God’s Word? The printing press had not yet been invented, and it took 10 months for one person to copy a single Bible by hand. Wycliffe recruited a group of men that shared his passion for spreading God’s Word, and they became known as “Lollards.” Many Lollards left worldly possessions behind and embraced an ascetic life-style, setting out across England dressed in only basic clothing, a staff in one hand, and armed with an English Bible. They went to preach Christ to the common people The Roman Catholic clergy set out to destroy this movement, passing laws against the "Lollard" teaching and their Bibles. When the Lollards were caught, they were tortured and burned at the stake. A Lollard knew that when he received a Bible from John Wycliffe and was sent out to preach, he was mostly likely going to his own death. -

Calvinism Or Arminianism? They Have Both Led to Confusion, Division and False Teaching

Is Calvinism or Arminianism Biblical? A Biblical Explanation of the Doctrine of Election. By Cooper P. Abrams, III (*All rights reserved) [Comments from some who read this article] [Frequently Asked Questions About Calvinism] Is Calvinism or Arminianism Biblical? One of the most perplexing problems for the teacher of God's Word is to explain the relationship between the doctrine of election and the doctrine of salvation by grace. These two doctrines are widely debated by conservative Christians who divide themselves into two opposing camps, the "Calvinists" and the "Arminians." To understand the problem let us look at the various positions held, the terms used, a brief history of the matter, and then present a biblical solution that correctly addresses the issue and avoids the unbiblical extremes of both the Calvinists and the Arminians. Introduction to Calvinism John Calvin, the Swiss reformer (1509-1564) a theologian, drafted the system of Soteriology (study of salvation) that bears his name. The term "Calvinism" refers to doctrines and practices that stemmed from the works of John Calvin. The tenants of modern Calvinism are based on the works of Calvin that have been expanded by his followers. These beliefs became the distinguishing characteristics of the Reformed churches and some Baptists. Simply stated, this view claims that God predestined or elected some to be saved and others to be lost. Those elected to salvation are decreed by God to receive salvation and cannot "resist God's grace." However, those that God elected to be lost are born condemned eternally to the Lake of Fie and He will not allow them be saved. -

Predestination and Freedom in Milton's Paradise Lost

SJT 59(1): 64–80 (2006) Printed in the United Kingdom C 2006 Scottish Journal of Theology Ltd doi:10.1017/S0036930605001614 Predestination and freedom in Milton’s Paradise Lost Benjamin Myers The University of Queensland, Brisbane QLD 4072, Australia [email protected] Abstract John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost (1667) offers a highly creative seventeenth- century reconstruction of the doctrine of predestination, a reconstruction which both anticipates modern theological developments and sheds important light on the history of predestinarian thought. Moving beyond the framework of post-Reformation controversies, the poem emphasises both the freedom and the universality of electing grace, and the eternally decisive role of human freedom in salvation. The poem erases the distinction between an eternal election of some human beings and an eternal rejection of others, portraying reprobation instead as the temporal self-condemnation of those who wilfully reject their own election and so exclude themselves from salvation. While election is grounded in the gracious will of God, reprobation is thus grounded in the fluid sphere of human decision. Highlighting this sphere of human decision, the poem depicts the freedom of human beings to actualise the future as itself the object of divine predestination. While presenting its own unique vision of predestination, Paradise Lost thus moves towards the influential and distinctively modern formulations of later thinkers like Schleiermacher and Barth. Modern attempts to reformulate the idea of divine