Comparison of John Wyclif and Jan Hus James E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Importance of the Reformation

Do you have a Bible in the English language in your home? Did you know that it was once illegal to own a Bible in the common language? Please take a few minutes to read this very, very brief history of Christianity. Most modern-day Christians do not know our history—but we should! The New Testament church was founded by Jesus Christ, but it has faced opposition throughout its history. In the 50 years following the death and resurrection of Jesus, most of His 12 apostles were killed for preaching the gospel of Jesus Christ. The Roman government hated Christians because they wouldn’t bow down to their false gods or to Caesar and continued to persecute and kill Christians, such as Polycarp who they martyred in 155 AD. Widespread persecution and killing of Christians continued until 313 AD, when the emperor Constantine declared Christianity to be legal. His proclamation caused most of the persecution to stop, but it also had a side effect—the church and state began to rule the people together, effectively giving birth to the Roman Catholic Church. Over time, the Roman Catholic Church gained more and more power—but unfortunately, they became corrupted by that power. They gradually began to add things to the teachings found in the Bible. For example, they began to sell indulgences to supposedly help people spend less time in purgatory. However, the idea of purgatory is not found in the Bible, and the idea that money can improve one’s favor with God shows a complete lack of understanding of the truth preached by Jesus Christ. -

KAS International Reports 10/2015

38 KAS INTERNATIONAL REPORTS 10|2015 MICROSTATE AND SUPERPOWER THE VATICAN IN INTERNATIONAL POLITICS Christian E. Rieck / Dorothee Niebuhr At the end of September, Pope Francis met with a triumphal reception in the United States. But while he performed the first canonisation on U.S. soil in Washington and celebrated mass in front of two million faithful in Philadelphia, the attention focused less on the religious aspects of the trip than on the Pope’s vis- its to the sacred halls of political power. On these occasions, the Pope acted less in the role of head of the Church, and therefore Christian E. Rieck a spiritual one, and more in the role of diplomatic actor. In New is Desk officer for York, he spoke at the United Nations Sustainable Development Development Policy th and Human Rights Summit and at the 70 General Assembly. In Washington, he was in the Department the first pope ever to give a speech at the United States Congress, of Political Dialogue which received widespread attention. This was remarkable in that and Analysis at the Konrad-Adenauer- Pope Francis himself is not without his detractors in Congress and Stiftung in Berlin he had, probably intentionally, come to the USA directly from a and member of visit to Cuba, a country that the United States has a difficult rela- its Working Group of Young Foreign tionship with. Policy Experts. Since the election of Pope Francis in 2013, the Holy See has come to play an extremely prominent role in the arena of world poli- tics. The reasons for this enhanced media visibility firstly have to do with the person, the agenda and the biography of this first non-European Pope. -

John XXIII & Idea of a Council

POPE JOHN XXIII AND THE IDEA OF AN ECUMENICAL COUNCIL Joseph A. Komonchak On January 25, 1959, just three months after he had assumed the papacy, Pope John XXIII informed a group of Cardinals at St. Paul's outside the Walls that he intended to convoke an ecumenical council. The announcement appeared towards the end of a speech closing that year's celebration of the Chair of Unity Octave, which the Pope used in order to comment on his initial experiences as Pope and to meet the desire to know the main lines his pontificate would follow.1 The first section offered what might be called a pastoral assessment of the challenges he faced both as Bishop of Rome and as supreme Pastor of the universal Church. The reference to his responsibilities as Bishop of Rome is already significant, given that this local episcopal role had been greatly eclipsed in recent centuries, most of the care for the city having been assigned to a Cardinal Vicar, while the pope focused on universal problems. Shortly after his election, Pope John had told Cardinal Tardini that he intended to be Pope "quatenus episcopus Romae, as Bishop of Rome." With regard to the city, the Pope noted all the changes that had taken place since in the forty years since he had worked there as a young priest. He noted the great growth in the size and population of Rome and the new challenges it placed on those responsible for its spiritual well-being. Turning to the worldwide situation, the Pope briefly noted that there was much to be joyful about. -

Forerunners to the Reformation

{ Lecture 19 } FORERUNNERS TO THE REFORMATION * * * * * Long before Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the Wittenberg Door, there were those who recognized the corruption within the Roman Catholic Church and the need for major reform. Generally speaking, these men attempted to stay within the Catholic system rather than attempting to leave the church (as the Protestant Reformers later would do). The Waldensians (1184–1500s) • Waldo (or Peter Waldo) lived from around 1140 to 1218. He was a merchant from Lyon. But after being influenced by the story of the fourth-century Alexius (a Christian who sold all of his belongings in devotion to Christ), Waldo sold his belongings and began a life of radical service to Christ. • By 1170, Waldo had surrounded himself with a group of followers known as the Poor Men of Lyon, though they would later become known as Waldensians. • The movement was denied official sanction by the Roman Catholic Church (and condemned at the Third Lateran Council in 1179). Waldo was excommunicated by Pope Lucius III in 1184, and the movement was again condemned at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. • Waldensians were, therefore, persecuted by the Roman Catholics as heretics. However, the movement survived (even down to the present) though the Waldensians were often forced into hiding in the Alps. • The Waldensian movement was characterized by (1) voluntary poverty (though Waldo taught that salvation was not restricted to those who gave up their wealth), (2) lay preaching, and (2) the authority of the Bible (translated in the language of the people) over any other authority. -

Crescentii Family 267

CRESCENTII FAMILY 267 Carson, Thomas, ed. and trans. Barbarossa in Italy.New York: under the same title, see Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Italica, 1994. Pisa, 22, 1953, pp. 3–49.) Cavalcabo`, Agostino. Le ultime lotte del comune di Cremona per Waley, Daniel. The Italian City-Republics, 3rd ed. London and New l’autonomia: Note di storia lombarda dal 1310 al 1322.Cremona: York: Longman, 1988. Regia Deputazione di Storia Patria, 1937. Wickham, Chris. Early Medieval Italy: Central Power and Local Falconi, Ettore, ed. Le carte cremonesi dei secoli VIII–XII,2vols. Society, 400–1000. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, Cremona: Biblioteca Statale, 1979–1984, Vol. 1, pp. 759–1069; 1989. Vol. 2, pp. 1073–1162. BARBARA SELLA Fanning, Steven C. “Lombard League.” In The Dictionary of the Middle Ages, ed. Joseph Strayer, Vol. 7. New York: Scribner, 1986, pp. 652–653. Gualazzini, Ugo. Il “populus” di Cremona e l’autonomia del comune. CRESCENTII FAMILY Bologna: Zanichelli, 1940. Several men whose name, Crescentius, appears in tenth- and MMM . Statuta et ordinamenta Comunis Cremonae facta et compilata eleventh-century documents from the vicinity of Rome are currente anno Domine MCCCXXXIX: Liber statutorum Comunis grouped together as a family, the Crescentii. As Toubert (1973) Vitelianae (saec. XIIV).Milan: Giuffre`, 1952. has indicated, the term Crescentii was not used by the medieval MMM. Gli organi assembleari e collegiali del comune di Cremona nell’eta` viscontea-sforzesca.Milan: Giuffre`, 1978. sources, and the “family” called by that name is a creation of Hyde, John Kenneth. Society and Politics in Medieval Italy: The modern historiography. -

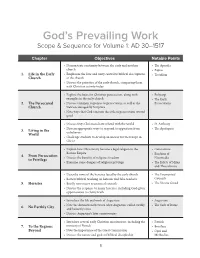

Scope & Sequence

God’s Prevailing Work Scope & Sequence for Volume 1: AD 30–1517 Chapter Objectives Notable Points • Demonstrate continuity between the early and modern • The Apostles church • Papias 1. Life in the Early • Emphasize the love and unity central to biblical descriptions • Tertullian Church of the church • Discuss the priorities of the early church, comparing them with Christian activity today • Explore the basis for Christian persecution, along with • Polycarp examples in the early church • The Early 2. The Persecuted • Discuss common responses to persecution, as well as the Persecutions Church view encouraged by Scripture • Note ways that God can turn the evils of persecution toward good • Discuss ways Christians have related with the world • St. Anthony • Discern appropriate ways to respond to opposition from • The Apologists 3. Living in the unbelievers World • Challenge students to develop an answer for their hope in Christ • Explain how Christianity became a legal religion in the • Constantine Roman Empire • Eusebius of 4. From Persecution • Discuss the benefits of religious freedom Nicomedia to Privilege • Examine some dangers of religious privilege • The Edicts of Milan and Thessalonica • Describe some of the heresies faced by the early church • The Ecumenical • Review biblical teaching on heresies and false teachers Councils 5. Heresies • Briefly note major ecumenical councils • The Nicene Creed • Discuss the response to major heresies, including God-given opportunities to clarify truth • Introduce the life and work of Augustine • Augustine • Note the distinctions between what Augustine called earthly • The Sack of Rome 6. No Earthly City and heavenly cities • Discuss Augustine’s later controversies • Introduce several early Christian missionaries, including the • Patrick 7. -

What Happened in the First Century -- Creation of New Testament Writings; Spread of Christianity; Rise of Persecutions

What Happened in the First Century -- Creation of New Testament Writings; Spread of Christianity; Rise of Persecutions • The words and sayings of Jesus are collected and preserved. New Testament writings are completed. • A new generation of leaders succeeds the apostles. Nevertheless, expectation still runs high that the Lord may return at any time. The end must be close. • The Gospel taken through a great portion of the known world of the Roman empire and even to regions beyond. • New churches at first usually begin in Jewish synagogues around the empire and Christianity is seen at first as a part of Judaism. • The Church faces a major crisis in understanding itself as a universal faith and how it is to relate to its Jewish roots. • Christianity begins to emerge from its Jewish womb. A key transition takes place at the time of Jewish Revolt against Roman authority. In 70 AD Christians do not take part in the revolt and relocate to Pella in Jordan. • The Jews at Jamnia in 90 AD confirm the canon of the Hebrew Scriptures. The same books are recognized as authoritative by Christians. • Persecutions test the church. Jewish historian Josephus seems to express surprise that they are still in existence in his Antiquities in latter part of first century. • Key persecutions include Nero at Rome who blames Christians for a devastating fire that ravages the city in 64 AD He uses Christians as human torches to illumine his gardens. • Emperor Domitian demands to be worshiped as "Lord and God." During his reign the book of Revelation is written and believers cannot miss the reference when it proclaims Christ as the one worthy of our worship. -

ADTH 3002 01—Conciliar Traditions of the Catholic Church II: Trent To

ADTH 3002 01—Conciliar Traditions of the Catholic Church II: Trent to Vatican II (3 cr) Woods College of Advancing Studies Spring 2018 Semester, January 16 – May 14, 2018 Tu 6:00–8:30PM Instructor Name: Boyd Taylor Coolman BC E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 617-552-3971 Office: Stokes Hall 321N Office Hours: Tuesday 4:00PM-5:00PM Boston College Mission Statement Strengthened by more than a century and a half of dedication to academic excellence, Boston College commits itself to the highest standards of teaching and research in undergraduate, graduate and professional programs and to the pursuit of a just society through its own accomplishments, the work of its faculty and staff, and the achievements of its graduates. It seeks both to advance its place among the nation's finest universities and to bring to the company of its distinguished peers and to contemporary society the richness of the Catholic intellectual ideal of a mutually illuminating relationship between religious faith and free intellectual inquiry. Boston College draws inspiration for its academic societal mission from its distinctive religious tradition. As a Catholic and Jesuit university, it is rooted in a world view that encounters God in all creation and through all human activity, especially in the search for truth in every discipline, in the desire to learn, and in the call to live justly together. In this spirit, the University regards the contribution of different religious traditions and value systems as essential to the fullness of its intellectual life and to the continuous development of its distinctive intellectual heritage. -

Chronology of the Reformation 1320: John Wycliffe Is Born in Yorkshire

Chronology of the Reformation 1320: John Wycliffe is born in Yorkshire, England 1369?: Jan Hus, born in Husinec, Bohemia, early reformer and founder of Moravian Church 1384: John Wycliffe died in his parish, he and his followers made the first full English translation of the Bible 6 July 1415: Jan Hus arrested, imprisoned, tried and burned at the stake while attending the Council of Constance, followed one year later by his disciple Jerome. Both sang hymns as they died 11 November 1418: Martin V elected pope and Great Western Schism is ended 1444: Johannes Reuchlin is born, becomes the father of the study of Hebrew and Greek in Germany 21 September 1452: Girolamo Savonarola is born in Ferrara, Italy, is a Dominican friar at age 22 29 May 1453 Constantine is captured by Ottoman Turks, the end of the Byzantine Empire 1454?: Gütenberg Bible printed in Mainz, Germany by Johann Gütenberg 1463: Elector Fredrick III (the Wise) of Saxony is born (died in 1525) 1465 : Johannes Tetzel is born in Pirna, Saxony 1472: Lucas Cranach the Elder born in Kronach, later becomes court painter to Frederick the Wise 1480: Andreas Bodenstein (Karlstadt) is born, later to become a teacher at the University of Wittenberg where he became associated with Luther. Strong in his zeal, weak in judgment, he represented all the worst of the outer fringes of the Reformation 10 November 1483: Martin Luther born in Eisleben 11 November 1483: Luther baptized at St. Peter and St. Paul Church, Eisleben (St. Martin’s Day) 1 January 1484: Ulrich Zwingli the first great Swiss -

JOHN WYCLIFFE "Morning Star of the Reformation"

JOHN WYCLIFFE "Morning Star of the Reformation" The Gospel light began to shine in the 1300’s when John Wycliffe, the “Morn- ing Star of the Reformation,” began to speak out against the abuses and false teachings prevalent within the Roman Catholic Church in England. An influential teacher at Oxford, Wycliffe was expelled from his teaching position because of his outspoken stance. Wycliffe was convinced that every man, woman, and child had the right to read God’s Word in their own language. He knew that only the Scriptures could break the bondage that enslaved the people. With the help of his followers, he completed his Middle English translation in 1382 -- the first English translation of the Bible. But how to spread God’s Word? The printing press had not yet been invented, and it took 10 months for one person to copy a single Bible by hand. Wycliffe recruited a group of men that shared his passion for spreading God’s Word, and they became known as “Lollards.” Many Lollards left worldly possessions behind and embraced an ascetic life-style, setting out across England dressed in only basic clothing, a staff in one hand, and armed with an English Bible. They went to preach Christ to the common people The Roman Catholic clergy set out to destroy this movement, passing laws against the "Lollard" teaching and their Bibles. When the Lollards were caught, they were tortured and burned at the stake. A Lollard knew that when he received a Bible from John Wycliffe and was sent out to preach, he was mostly likely going to his own death. -

Divine Discontent: Betty Friedan and Pope John XIII in Conversation

Australian eJournal of Theology 8 (October 2006) Divine Discontent: Betty Friedan and Pope John XIII in Conversation Sophie McGrath RSM Abstract: This paper is about ideas, values and attitudes in the turbulent times of the 1960s. It brings into conversation the feminist Betty Friedan and Pope John XIII in critiquing contemporary academic disciplines as well as authority, feminism, marriage, relationships between men and women, motherhood, the family, sexuality, and human dignity. It juxtaposes a secular and a Catholic tradition. Though the literary devise of the dinner party is used to facilitate the participants speaking in their own words and to highlight their humanity, this essay is essentially an academic exercise. It is designed to challenge readers to reconsider popular perceptions of feminism and the papacy in general and Betty Friedan and Pope John XXIII in particular.1 Key Words: Betty Frieden; John XXIII; feminism and Catholicism; The Feminine Mystique; gender relations; sexuality; authority; family life he period of prosperity accompanying post-war reconstruction in Europe, USA and the Pacific area in the late 1940s and into the 1950s brought with it a consumer culture generated by technological advances in industry. Factories churned out the goods and the burgeoning advertising industry, through newspaper, radio and TV, influenced the buying habits and life-style of the public. The prominent philosophy of atheistic existentialism encouraged an ever-increasing challenging of authority. In the post-war period of prosperity the West was less threatened by the menace of communism at home, but the aggressive foreign policy of Russia generated considerable fear among both secular and Church leaders. -

Health Care Delivery in Light of the Gospel Challenge William Paul Saunders

The Linacre Quarterly Volume 51 | Number 1 Article 7 February 1984 Health Care Delivery in Light of the Gospel Challenge William Paul Saunders Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq Recommended Citation Saunders, William Paul (1984) "Health Care Delivery in Light of the Gospel Challenge," The Linacre Quarterly: Vol. 51 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq/vol51/iss1/7 due to an eroded tax base from unemployment. And the list could continue. The problem, however, cannot be analyzed nor a solution envisioned simply through economics. Looking at balance sheets, expenditure reports, and budgets misses the mark by ignoring a more fundamental concern - the individual human being. Health care Health Care Delivery transcends financial exigencies. By its nature, health care is intimately related to the welfare of the people, so any solution must likewise be in Light of the Gospel Challenge oriented to satisfying the needs of the people. William Paul Saunders Concern Rooted in Scripture This concern for the· individual person is rooted in Sacred Scripture and reflected in the Roman Catholic Church's magisterial teaching. The Genesis account of creation attests, "God created man in His image; in the divine image He created him; male and female He created them" (Genesis 1:27). Since man is the pinnacle of creation, human The author, a student at St. life has been and must continue to be revered as sacred, possessing an Charles Borromeo Seminary in inherent dignity. If valued as such, human life naturally engenders a Philadelphia, is working toward . concern for health, which in the Hebraic vision captured man in his his master's degree in theology multi-faceted entirety, as a whole being- not only in his physical, and will be ordained a priest in spiritual, and psychological dimensions, but also in his social and insti May, 1984.