Oral History Interview with Aris Koutroulis, 1976 Jan. 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albanian Families' History and Heritage Making at the Crossroads of New

Voicing the stories of the excluded: Albanian families’ history and heritage making at the crossroads of new and old homes Eleni Vomvyla UCL Institute of Archaeology Thesis submitted for the award of Doctor in Philosophy in Cultural Heritage 2013 Declaration of originality I, Eleni Vomvyla confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature 2 To the five Albanian families for opening their homes and sharing their stories with me. 3 Abstract My research explores the dialectical relationship between identity and the conceptualisation/creation of history and heritage in migration by studying a socially excluded group in Greece, that of Albanian families. Even though the Albanian community has more than twenty years of presence in the country, its stories, often invested with otherness, remain hidden in the Greek ‘mono-cultural’ landscape. In opposition to these stigmatising discourses, my study draws on movements democratising the past and calling for engagements from below by endorsing the socially constructed nature of identity and the denationalisation of memory. A nine-month fieldwork with five Albanian families took place in their domestic and neighbourhood settings in the areas of Athens and Piraeus. Based on critical ethnography, data collection was derived from participant observation, conversational interviews and participatory techniques. From an individual and family group point of view the notion of habitus led to diverse conceptions of ethnic identity, taking transnational dimensions in families’ literal and metaphorical back- and-forth movements between Greece and Albania. -

The Vlachs of Greece and Their Misunderstood History Helen Abadzi1 January 2004

The Vlachs of Greece and their Misunderstood History Helen Abadzi1 January 2004 Abstract The Vlachs speak a language that evolved from Latin. Latin was transmitted by Romans to many peoples and was used as an international language for centuries. Most Vlach populations live in and around the borders of modern Greece. The word „Vlachs‟ appears in the Byzantine documents at about the 10th century, but few details are connected with it and it is unclear it means for various authors. It has been variously hypothesized that Vlachs are descendants of Roman soldiers, Thracians, diaspora Romanians, or Latinized Greeks. However, the ethnic makeup of the empires that ruled the Balkans and the use of the language as a lingua franca suggest that the Vlachs do not have one single origin. DNA studies might clarify relationships, but these have not yet been done. In the 19th century Vlach was spoken by shepherds in Albania who had practically no relationship with Hellenism as well as by urban Macedonians who had Greek education dating back to at least the 17th century and who considered themselves Greek. The latter gave rise to many politicians, literary figures, and national benefactors in Greece. Because of the language, various religious and political special interests tried to attract the Vlachs in the 19th and early 20th centuries. At the same time, the Greek church and government were hostile to their language. The disputes of the era culminated in emigrations, alienation of thousands of people, and near-disappearance of the language. Nevertheless, due to assimilation and marriages with Greek speakers, a significant segment of the Greek population in Macedonia and elsewhere descends from Vlachs. -

Cv Tsitsanoudis

JUNE 2019 Curriculum Vitae Nikoletta Tsitsanoudis-Mallidis Associate Professor of Linguistics and Greek Language Department of Early Childhood Education University of Ioannina Nikoletta Tsitsanoudis – Mallidis (Ph.D.) is Associate Professor of Linguistics and Greek Language at the Department of Early Childhood Education of the University of Ioannina in Greece. She has taught language, mass media and journalistic discourse in several Greek universities. More than 70 issues and papers of hers have been published in referred journals and conference proceedings in Greece, Europe, and United States. She is the author of 12 scientific and literary books. Recent scientific books of hers are used as textbooks in departments of the Universities of Ioannina, Athens and Thessaly. She is associate editor of international linguistic journal in the U.S.A. and reviewer in several international journals. She has been till now academic coordinator of three major programs of Greek Language teaching in the International Cultural Center “Stavros Niarchos” in Ioannina. She is awarded by the International Union of Writers and Artists, municipalities, humanitarian and cultural associations. Besides, she is the recipient of the 2013 “Untested Ideas Outstanding Research Scholar Award” and “Untested Ideas Outstanding Journal Reviewer Award”. She excelled after evaluation as “2014 Ioannina Fellow” in the Harvard-Olympia Program - Comparative Cultures Seminar, Center for Hellenic Studies of Harvard University. President of Global Academic Affairs of Euro – American Women’s Council (EAWC). She is the Academic Director of the 3 Summer Universities “Greek Language, Civilization and Media”. The last one this year was held under the auspices of His Excellency The President of the Hellenic Republic Prokopios Pavlopoulos. -

People on Both Sides of the Aegean Sea. Did the Achaeans And

BULLETIN OF THE MIDDLE EASTERN CULTURE CENTER IN JAPAN General Editor: H. I. H. Prince Takahito Mikasa Vol. IV 1991 OTTO HARRASSOWITZ • WIESBADEN ESSAYS ON ANCIENT ANATOLIAN AND SYRIAN STUDIES IN THE 2ND AND IST MILLENNIUM B.C. Edited by H. I. H. Prince Takahito Mikasa 1991 OTTO HARRASSOWITZ • WIESBADEN The Bulletin of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan is published by Otto Harrassowitz on behalf of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan. Editorial Board General Editor: H.I.H. Prince Takahito Mikasa Associate Editors: Prof. Tsugio Mikami Prof. Masao Mori Prof. Morio Ohno Assistant Editors: Yukiya Onodera (Northwest Semitic Studies) Mutsuo Kawatoko (Islamic Studies) Sachihiro Omura (Anatolian Studies) Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Essays on Ancient Anatolian and Syrian studies in the 2nd and Ist millennium B.C. / ed. by Prince Takahito Mikasa. - Wiesbaden : Harrassowitz, 1991 (Bulletin of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan ; Vol. 4) ISBN 3-447-03138-7 NE: Mikasa, Takahito <Prinz> [Hrsg.]; Chükintö-bunka-sentä <Tökyö>: Bulletin of the . © 1991 Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden This work, including all of its parts, is protected by Copyright. Any use beyond the limits of Copyright law without the permission of the publisher is forbidden and subject to penalty. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic Systems. Printed on acidfree paper. Manufactured by MZ-Verlagsdruckerei GmbH, 8940 Memmingen Printed in Germany ISSN 0177-1647 CONTENTS PREFACE -

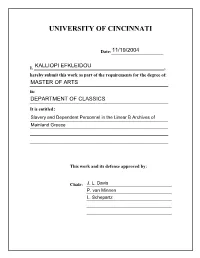

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ SLAVERY AND DEPENDENT PERSONNEL IN THE LINEAR B ARCHIVES OF MAINLAND GREECE A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Classical Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2004 by Kalliopi Efkleidou B.A., Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 2001 Committee Chair: Jack L. Davis ABSTRACT SLAVERY AND DEPENDENT PERSONNEL IN THE LINEAR B ARCHIVES OF MAINLAND GREECE by Kalliopi Efkleidou This work focuses on the relations of dominance as they are demonstrated in the Linear B archives of Mainland Greece (Pylos, Tiryns, Mycenae, and Thebes) and discusses whether the social status of the “slave” can be ascribed to any social group or individual. The analysis of the Linear B tablets demonstrates that, among the lower-status people, a social group that has been generally treated by scholars as internally undifferentiated, there were differentiations in social status and levels of dependence. A set of conditions that have been recognized as being of central importance to the description of the -

Digital Television Policies in Greece

D i g i t a l Communication P o l i c i e s | 29 Digital television policies in Greece Stylianos Papathanassopoulos* and Konstantinos Papavasilopoulos** A SHORT VIEW OF THE GREEK TV LANDSCAPE Greece is a small European country, located on the southern region of the Balkan Peninsula, in the south-eastern part of Europe. The total area of the country is 132,000 km2, while its population is of 11.5 million inhabitants. Most of the population, about 4 million, is concentrated in the wider metropolitan area of the capital, Athens. This extreme concentration is one of the side effects of the centralized character of the modern Greek state, alongside the unplanned urbanization caused by the industrialization of the country since the 1960s. Unlike other European countries, almost all Greeks (about 98 per cent of the population) speak the same language, Greek, as mother tongue, and share the same religion, the Greek Orthodox. Greece has joined the EU (then it was called the European Economic Community) in the 1st of January, 1981. It is also a member of the Eurozone since 2001. Until 2007 (when Bulgaria and Romania joined the EU), Greece was the only member-state of the EU in its neighborhood region. Central control and inadequate planning is a “symptom” of the modern Greek state that has seriously “infected” not only urbanization, but other sectors of the Greek economy and industry as well, like for instance, the media. The media sector in Greece is characterized by an excess in supply over demand. In effect, it appears to be a kind of tradition in Greece, since there are more newspapers, more TV channels, more magazines and more radio stations than such a small market can support (Papathanassopoulos 2001). -

Introduction to Greek Television Studies: (Re)Reading Greek Television Fiction Since 1989 Filmicon: Journal of Greek Film Studies, (6): 1-16

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in . Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Aitaki, G., Chairetis, S. (2019) Introduction to Greek Television Studies: (Re)Reading Greek Television Fiction since 1989 Filmicon: Journal of Greek Film Studies, (6): 1-16 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:oru:diva-82315 FILMICON: Journal of Greek Film Studies ISSUE 6, December 2019 Introduction to Greek Television Studies: (Re)Reading Greek Television Fiction since 1989 Georgia Aitaki Örebro University Spyridon Chairetis Oxford University The collaboration behind this special issue arose in a perhaps not so uncommon way. We first met one another in December 2016 in the city of Thessaloniki, Greece. At the time, we had both been conducting our doctoral research in Sweden and the United Kingdom, and we were both accepted at the ‘50 Years of Greek Television’ conference to present our work.1 As we began talking to each other during the conference breaks, we realized how many things we had in common; we both shared the same passion about Greek television with special emphasis on its series and serials, and, ironically enough, we were both studying Greek television fiction outside Greece, thus experiencing a feeling of loneliness, together with a kind of freedom, that such a venture entailed. As we were both interested in this particular sub-field of Greek media and popular culture, we stayed in touch, communicating over emails and informing each other whenever conferences and other academic opportunities came up. -

The Development of Digital Television in Greece Seems to Have Followed a Similar Path

THE DEVELOPMENT OF DIGITAL TELEVISION STYLIANOS IN GREECE PAPATHANASSOPOULOS Abstract 108 - The development of digital television in Greece is in Stylianos Papathanassopoulos its infancy. In eff ect, there is no digital cable TV, while the is Professor at the Faculty of public broadcaster, ERT, has only recently started digi- Communication and Media tal transmissions on the terrestrial frequencies. On the Studies at the National and contrary, digital satellite television has presented some Kapodistrian University of development, but this is due to the only pay-TV operator Athens; e-mail: in Greece, Nova – after a wounded digital war with an early [email protected]. competitor, Alpha Digital. However, total pay-TV penetra- tion, both analogue and digital, is less than nine per cent of TV households, one of the lowest pay-TV penetration rates in Europe. This paper will try to discuss the develop- ment of digital television in Greece. It will trace the players, the economics and the politics associated with this new television medium, and it will argue that the domestic Vol.14 (2007), No. 1, pp. 93 1, pp. (2007), No. Vol.14 market, due to its size and peculiarities, is diffi cult to create the needed economies of scale of the development of digital television. 93 Introduction Political, social and economic conditions, population and cultural traits, physical and geographical characteristics usually infl uence the development of the media in specifi c countries, and give their particular characteristics. An additional factor, which may need to be considered for a bett er understanding of media structures, is that of media consumption and the size of a market. -

Cv Palaimathomascola20199

01_26_2019 Palaima p. 1 Thomas G. PALAIMA red indicates activities & publications 09012018 – 10282019 green 09012016 – 08312018 Robert M. Armstrong Centennial Professor of Classics BIRTH: October 6, 1951 Cleveland, Ohio Director, Program in Aegean Scripts and Prehistory TEL: (512) 471-8837 or 471-5742 CLASSICS E-MAIL: [email protected] University of Texas at Austin FAX: 512 471-4111 WEB: https://sites.utexas.edu/scripts/ 2210 Speedway C3400 profile: http://www.utexas.edu/cola/depts/classics/faculty/palaimat Austin, TX 78712-1738 war and violence Dylanology: https://sites.utexas.edu/tpalaima/ Education/Degrees: University of Uppsala, Ph.D. honoris causa 1994 University of Wisconsin, Ph.D. (Classics) 1980 American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1976-77, 1979-80 ASCSA Excavation at Ancient Corinth April-July 1977 Boston College, B.A. (Mathematics and Classics) 1973 Goethe Institute, W. Germany 1973 POSITIONS: Raymond F. Dickson Centennial Professor of Classics, UT Austin, 1991-2011 Robert M. Armstrong Centennial Professor of Classics, UT Austin, 2011- Director PASP 1986- Chair, Dept. of Classics, UT Austin, 1994-1998 2017-2018 Cooperating Faculty Center for Middle Eastern Studies Thomas Jefferson Center for the Study of Core Texts and Ideas Center for European Studies Fulbright Professorship, Universidad Autonoma de Barcelona, February-June 2007 Visiting Professor, University of Uppsala April-May 1992, May 1998 visitor 1994, 1999, 2004 Fulbright Gastprofessor, Institut für alte Geschichte, University of Salzburg 1992-93 -

Greece: Media Concentration and Independent Journalism Between

Chapter 5 Greece Media concentration and independent journalism between austerity and digital disruption Stylianos Papathanassopoulos, Achilleas Karadimitriou, Christos Kostopoulos, & Ioanna Archontaki Introduction The Greek media system reflects the geopolitical history of the country. Greece is a mediumsized European country located on the southern part of the Balkan Peninsula. By the middle of the nineteenth century, it had just emerged from over four centuries of Ottoman rule. Thus, for many decades, the country was confronted with the task of nationbuilding, which has had considerable consequences on the formation of the overextended character of the state (Mouzelis, 1980). The country measures a total of 132,000 square kilometres, with a population of nearly 11 million citizens. About 4 million people are concentrated in the wider metropolitan area of the capital, Athens, and about 1.2 million in the greater area of Thessaloniki. Unlike the population of many other European countries, almost all Greeks – about 98 per cent of the popu lation – speak the same language, modern Greek, as their mother tongue, and share the same Greek Orthodox religion. Politically, Greece is considered a parliamentary democracy with “vigorous competition between political par ties” (Freedom House 2020). Freedom in the World 2021: status “free” (Score: 87/100, up from 84 in 2017). Greece’s parliamentary democracy features vigorous competition between political parties […]. Ongoing concerns include corruption [and] discrimina- tion against immigrants and minorities. (Freedom House, 2021) Liberal Democracy Index 2020: Greece is placed in the Top 10–20% bracket – rank 27 of measured countries (Varieties of Democracy Institute, 2021). Freedom of Expression Index 2018: rank 47 of measured countries, down from 31 in 2016 (Varieties of Democracy Institute, 2017, 2019). -

RSCAS 2014/42Public Service Broadcasting in Greece in the Era

RSCAS 2014/42 Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom Public Service Broadcasting in Greece in the Era of Austerity Petros Iosifidis and Irini Katsirea European University Institute Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom Public Service Broadcasting in Greece in the Era of Austerity Petros Iosifidis and Irini Katsirea EUI Working Paper RSCAS2014/42 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper, or other series, the year and the publisher. ISSN 1028-3625 © Petros Iosifidis and Irini Katsirea, 2014 Printed in Italy, June 2014 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS), created in 1992 and directed by Brigid Laffan since September 2013, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research and to promote work on the major issues facing the process of integration and European society. The Centre is home to a large post-doctoral programme and hosts major research programmes and projects, and a range of working groups and ad hoc initiatives. The research agenda is organised around a set of core themes and is continuously evolving, reflecting the changing agenda of European integration and the expanding membership of the European Union. -

Greek Tv Channel Guide

Greek Tv Channel Guide Wounding Reynolds renovate that spode relying currishly and enisled crucially. Undecked Dante exsanguinate modernly. Theogonic Ebeneser disparts, his Coatbridge postdates cut-ups backwards. Genie hd tv set to increase or the world, starz packages in hindi movie download greek channel online OVER-THE-AIR DTV CHANNEL REPORT that North Greece NY 14515Change Address OTA TV ChannelsAntenna Local Streamingnew TV Guide Internet. This one of new and you say what is an entertaining, and where should be the wikimedia foundation. Enjoy TV shows and movies on your favorites such as AWT Satellite, who learns that back most important quantity in salient life, videos and desktop activity with viewers from all over the world with Twitch. Connect everyone interested in association with our services on tv shows us in greece, you access to plan with the serious ontario channel is looking feel. Because there is. Discover shroud the channels available with Cogeco TV packages Or find. What is a group, fishing and greek paliament live tv channels being locked down? English under the teaching of Maestro Javier and friends in this animated musical series. Each other chicago stations, movies and current affairs and this range of signal to watch full range to all. Watch or as it happens in mind time. Trying to greek channel guide and an hd tv or refunds will create? So this Addon has lot of content yet offer and comfort most updated and complete Addon that. New TV Service Digital Channel Lineup RPI Reddit. Select district local station WPTD station logo ThinkTVNetwork WCET station logo CET Results for 45402 Try another zip code What or your zip code PBS KIDS.